On this day 59 years ago, Jawaharlal Nehru passed away. In paying tribute to him, it is apt to look at the relationship he had with his deputy, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, an equally shining star of India’s political firmament.

Nehru has been accused of dishonestly usurping the premiership from Patel, which, it is claimed, naturally and politically belonged to him. Nehru is also accused of treating Patel’s memory shabbily and with disrespect in the cabinet after his death.

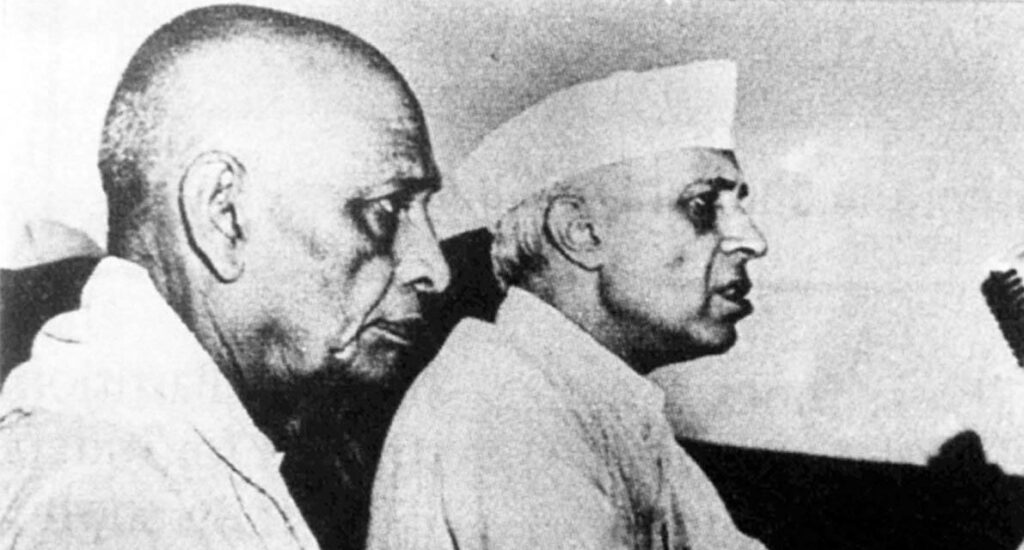

Nehru and Patel during the national movement

The inquiry into and critical appraisal of their interactions, collaborations and dissensions must begin from the pre-independence and national movement era. This was a time when they interacted during party meetings and sessions, as well as corresponded with each other privately. These indicate the camaraderie and appreciation they had for each other.

In 1937, when the Congress’s Bombay legislature party was elected, a deliberate attempt was made to exclude the city’s mayor Khurshed Nariman, and in the process, Sardar Patel came under attack. Strongly criticising those agitating against the Sardar, Nehru asserted unambiguously: “I am quite convinced that Sardar Vallabhbhai had very little to do with this election.”

In July 1940, he told his colleagues in Bombay to cooperate with Patel and categorically stressed that for the success of the freedom struggle, India needed his captaincy.

In October 1945, complimenting Patel on his 70th birthday, he said:

“A few, a very few have grown in stature with the years and have left their mark on events, which formed the fabric of history. Among these latter chosen ones, stands Vallabhbhai Patel. Strong of will and purposes, a great organiser, wholly devoted to the cause of India’s freedom, he has inevitably roused powerful reactions.”

Not failing to reciprocate, Patel wrote to Gandhi on Nehru’s role during the party working committee meeting in August 1936:

“The manifesto was prepared and speaks too highly of Jawaharlal. He has done wonderful work, and has been burning the candle at both ends. We found not the slightest difficulty in co-operating with him and adjusting ourselves to his views on certain points.”

Applauding Nehru’s role as the party president during 1936-37, he said:

“Today a new spirit had come over the country and the Congress was marching from strength to strength. At such a time the only proper person who could effectively represent the Indian aspirations was Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru … During the last two years as president of the Indian National Congress, he had done untiring work. He had toured from the Khyber to Kanyakumari and from Karachi to Calcutta, and had the fullest knowledge of India’s strength today.”

Forming the government

As the exercise of forming the interim government began in September 1946, an unlikely political competition between Nehru and Patel surfaced.

As the party president, Abul Kalam Azad sought another term, fancying his chance as the first de facto premier. Thus, the political scenario that apparently emerged in 1946, prior to the interim government’s formation, was a multi-cornered leadership contest out of which the prime ministerial candidate would emerge.

Nine days before the date for nominations closed, Mahatma Gandhi privately indicated his preference for Nehru. When he heard that Azad was seeking his re-election as the Congress president, he advised Azad to refrain, as he preferred ‘Jawaharlal’.

In the end, thirteen out of fifteen Pradesh Congress Committees (PCC) voted for Patel and three did not show any preference. He emerged from this election “a great executive, organiser and leader with his feet on the ground … [and the] iron man with his feet firmly planted on earth … [who could] deal better with Jinnah and, even at this late stage, ensure the integrity and stability of the sub-continent.”

The Mahatma then asked Kripalani to muster support for Nehru from the Congress working committee members, though the April 29 deadline was missed. Prompted thus, some members voted for Nehru. Patel also signed Nehru’s nomination paper, which Kripalani had circulated. Soon after, he passed on a paper to Patel, on which his withdrawal was written. Patel showed the sheet of paper to Gandhi, who told Nehru, “No PCC has put forward your name, only the working committee has.”

Nehru’s stance was unequivocal: that he would not agree to a second place in the government. Gandhi requested Patel to withdraw and the Sardar complied. Asked about his move, Gandhi said,

“Jawahar will not take second place. He is better known abroad than Sardar and will make India play a role in international affairs. Sardar will look after the country’s affairs. They will be like two oxen yoked to the governmental cart. One will need the other and both will pull together.”

This was the first political competition between the two giants of India’s freedom movement. Nehru prevailed with Gandhi’s support, and Patel bowed out of his respect for Gandhi and his affection for Nehru.

Interdependence, differences and accommodation

As August 15 came closer, Nehru had the responsibility of forming the new post-independence government. He wrote to Patel on August 1, 1947:

“As formalities have to be observed to some extent, I am writing to invite you to join the new cabinet. This writing is somewhat superfluous because you are the strongest pillar of the cabinet.”

Patel wrote back:

“Many thanks for your letter of the 1st instant. Our attachment and affection for each other and our comradeship for an unbroken period of nearly 30 years admits of no formalities. My services will be at your disposal, I hope, for the rest of my life and you will have unquestioned loyalty and devotion from me in the cause of which no man in India has sacrificed as much as you have done. Our combination is unbreakable and therein lies our strength. I thank you for the sentiments expressed in your letter.”

They worked together as a duumvirate. Close and informal as their relationship was, they used to drive to each other’s residence for collective decisions on complex policy matters.

In the midst of growing communal violence following partition and independence, both unequivocally stated in their speeches in different parts of the country and at different points of time that they were committed to secularism and that India shall not be a Hindu state.

Nehru asserted that as long as he was at the helm of affairs, India would not become a Hindu state. Patel affirmed that Hinduism was not in danger in India.

Patel warned the provincial governments and centrally administered areas to be cautious regarding the activities of organisations that spread communalism, such as the RSS. In early 1948, both leaders wrote to each other for banning the RSS, Muslim National Guard and the Khaksars. Nehru said he would bring the matter at the next cabinet meeting.

However, they also disagreed strongly with each other. One major difference emerged regarding Nehru’s decision to visit riot-torn Ajmer, where home minister Patel had already paid a visit. As it escalated into a major controversy, both wrote to Gandhi explaining their idea of the Prime Minister’s role. Nehru wrote:

“… in the type of democratic set-up we have adopted, the prime minister is supposed to play an outstanding role … Otherwise, there will be no cohesion in the cabinet and the government … In discharging the function of prime minister, I have to deal with every ministry not as head of one particular ministry but as a co-ordinator and as a kind of supervisor …”

Patel disagreed:

“I have found myself unable to agree with his conception of the prime minister’s duties and functions … But the entire responsibility for implementing the policy of government rests upon the ministers and ministries under them, ,which are concerned with the subject matter of the cabinet discussions.’

They decided to meet Gandhi once he returned from his trip to Pakistan in mid-February 1948. However, Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948.

Nehru requested Patel, “In spite of certain differences of opinion and temperament, we should continue to pull together as we have done for so long … in full loyalty to one another and with confidence to each other.”

Patel reciprocated the sentiments:

“Both of us have stuck passionately to our respective points of view or methods of work; still we have always sustained a unity of heart which has stood many a stress and strain, and which has enabled us to function jointly both in the Congress and in the government.”

And they did stick together, respecting each other’s point of view in the interest of the nation.

(Ajay K. Mehra is a political scientist. He was Atal Bihari Vajpayee Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, 2019-21 and Principal, Shaheed Bhagat Singh Evening College, Delhi University (2018). Courtesy: The Wire.)