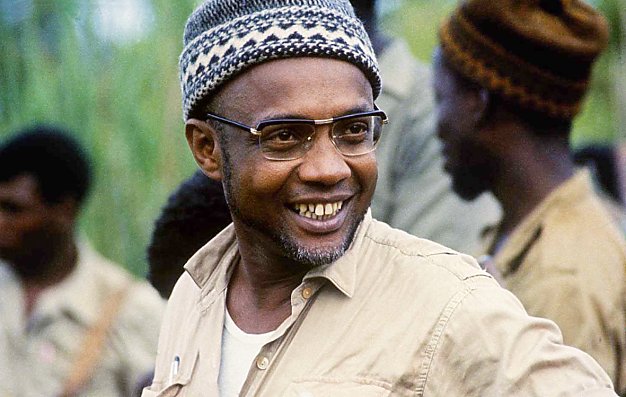

[During his life, Bissau-Guinean revolutionary Amilcar Cabral co-founded the PAIGC and dedicated his life to the liberation of his native Guinea and Cape Verde from Portuguese colonialism and capitalism-imperialism. One of his most celebrated works, Return to the Source, has recently been republished by Monthly Review Press. To mark this occasion, Bill Fletcher Jr., a member of The Real News Board of Directors, hosts a panel on the life and teachings of Cabral and his relevance to political movements today.

Polly Gaster began to work for the Mozambique Liberation Front, FRELIMO, in Dar-es-Salaam in 1967. She organized and ran the Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea from her home in the UK. Since Mozambique’s independence in 1975, she has lived and worked there in a variety of sectors

Craig Howard has more than 25 years of nonprofit experience, most of them in workforce and community economic development, designing and implementing replicable programs that create jobs and opportunities for disadvantaged people in the U.S. and abroad. Until his retirement, he served as a program director for the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Rozell “Prexy” Nesbitt was born and raised on Chicago’s West Side. A lifetime activist and intellectual, Nesbitt has lectured both in the United States and abroad, and has written extensively, publishing a book and articles in more than twenty international journals. Over the course of his career, Nesbitt made more than seventy trips to Africa, including trips taken in secret to apartheid torn South Africa; his work has garnered him numerous awards throughout his career.

Stephanie Urdang was born in South Africa and immigrated to the United States at the end of the 1960s. She became active in the anti-apartheid and solidarity movements in the late 1960’s onwards. She is a journalist, author of several books, and the co-founder of the NGO Rwanda Gift for Life.

Rush Transcript.]

● ●

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Hey, I’m Bill Fletcher and welcome to the Real News Network. We have a wonderful panel here. A panel constituted to commemorate the republication of a major book Return to the Source, a book of selected writings of the late Amilcar Cabral. Before we get into that, the morning, early morning, October 15th, 1972, I and a guy named Steve Pitts jumped into a Volkswagen Bug in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We were both students at Harvard, and we had heard that Amilcar Cabral was going to be speaking at Lincoln University. There was actually a group of us that were going to go down, but one person after another dropped by the wayside. And so it was left to me and Steve to drive all night to see Cabral. Which we did that afternoon, when he addressed a very large audience in a very hot room, delivering his presentation where he was receiving an honorary doctorate. None of us could have conceived of the idea that we were going to be among the last people to see Cabral alive, because in early 1973 he was murdered.

Cabral had a very, very important significance throughout the world, throughout the global left, in the movements of people of African descent. And this book, Return to the Source, when it came out, was very, very important in helping a broad audience get an appreciation of Cabral’s significance. Well, we’re going to talk about that today, and we have an opportunity with four wonderful guests. So we have joining us, Stephanie Urdang, who’s a South African-American. She was active in the US anti-apartheid movement and has worked for over two decades as a gender specialist for the United Nations. As a freelance journalist, she has published three books with Monthly Review Press, which is the publisher of this new edition, the most recent of hers being a memoir, Mapping My Way Home: Activism, Nostalgia, and the Downfall of Apartheid South Africa.

Also, joining us is Craig Howard, recently retired as program director at the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. Earlier in his career, Craig was a member of the African Information Service in New York. Also, Prexy Nesbitt is a college professor and former union organizer. He was active in the anti-apartheid movement and African solidarity movement on several continents, and comes from Chicago.

Finally, in an unplanned way, Polly Gaster started to work with the Mozambique Liberation Front, FRELIMO, in Dar es Salaam in 1967. Back in the United Kingdom, she organized and ran the Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea, during which time she met Amilcar Cabral. Since Mozambique’s independence in 1975, she has lived and worked there, mainly in various sectors of information and communication. And I want to welcome our guests and welcome you, the viewers. So I want to start with a question for all of you, and just think about this as a sort of living room discussion. Who was Amilcar Cabral, and why does he continue to have significance? And in answering this question, I’d like you to answer it as if you were speaking to someone who’s in their 20s or 30s, who may not be as well versed in the liberation struggles as we are. So who would like to start with this?

Polly Gaster: Okay. Can I?

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Please.

Polly Gaster: Let’s see. Well, Amilcar Cabral described himself in the quote on the cover of the book, least if it’s still there, which is something to the effect of, “I am a simple African man doing my duty in the context of my time.” And I think that is a good starting point because from that starting point, he became a leader of the liberation movement for the country that he was born in and grew up in and studied in, mostly. Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Cape Verde is an archipelago of islands, just off Guinea-Bissau on the West Coast of Africa. And he had a big advantage, I think, because he was an agronomist and he worked firstly in agronomy, he worked in a big colonial administration. And of course, both of those countries, both Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau were Portuguese colonies at the time, when he was a young man and beginning to work.

And from there he moved, through discussions and learning and enjoying and learning about resistance in Portugal and reading, he and some comrades established the Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Liberation Movement, PAIGC, and developed it. I think maybe I have just said enough. And he became a very well known leader, and he was part of a staggeringly good generation of African independence leaders in the Portuguese colonies, in Ghana and in Tanzania and other countries. And it was a generation that Africa was very lucky to have.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Prexy, same question.

Stephanie Urdang: Okay.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: No, Prexy.

Prexy Nesbitt: If I jump into this, I was really lucky, because I’d seen and met Cabral, at the very sad occasion of Eduardo Mondlane’s funeral in Dar es Salaam. And I think that was in February of ’69. And I met him there, I then think I saw him after that, if my memory serves me correctly, at the big conference that was held in Rome to support the peoples of the Portuguese colonies. And I was there and working and volunteering. And much to my surprise, I arrived the same day he showed up. And as he walked into the room, he saw me and he said, “Hello, Prexy.” And I was just shocked, that this man would even remember me at all. So that was something that I learned was a very powerful aspect of him. And then finally, just to kick this off and show what a human being he was, maybe Craig remembers this too, we met him at the airport to drive him to the Lincoln speech in Lincoln, Pennsylvania.

And I remember his getting into the car, and he was sitting directly in front of me. I was in the back, Bob Van Lupe was driving. And he went to get a cigarette, and he didn’t have his seatbelt on and the alarm went off. And Cabral jumped and he said, “What? What’s happening? What’s happening?” And we said, “You have to have your seatbelt on.” He said, “You all are in slavery. In this country, every aspect of you is in some kind of slavery all the time.” But what I found just wonderful about him, and would later have this borne out when my sister goes to hear him speak in New York at Jennifer Davis’s house, and I asked her to follow him to every speech he gave, and he finally noticed her writing with this weird handwriting she had. And this wonderful characteristic he had, of noticing people and remembering details about them, I think was one of the sources of his greatness.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. Stephanie, same question.

Stephanie Urdang: I mean, he was a great leader, as Polly said. For me, one of his strengths, or one of his number of strengths that I want to point to, was his ease in turning complex ideology and political analysis into simple words. So there wasn’t the sort of sense that you had to understand the great Marx’s analysis or something, you just really understood. And some of the things he would refer to was, “People are not fighting for ideas, they’re fighting for material benefit and we’ve got to be able to provide that, otherwise the revolution fails.” He also was not essentially a violent man. He did not think that violence was something that the revolution should follow, except that it had to, because of the violence of the Portuguese colonialism. I mean, as far as I know, there were no blowing ups of cafes or buses in Lisbon or Portugal.

They really focused on fighting the regime. And then another point that I took from him, which was really important to us in those days, was his emphasis on international solidarity. That was something that he really pushed. And it made us really feel more connected with him, as a result, and it gave us inspiration to continue in the struggle and the support for the revolution. And another point he made was that the revolution would not be successful without the support of the people, and this very clearly included women. So those are some of the takeaways I have, from what he taught me.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. Craig?

Craig Howard: As you know, I was a member of the African Information Service. And, during the early ’70s, I was also part of a number of organizations, primarily Black American organizations, that were providing support to the liberation movements and were involved in the anti-apartheid movement. And I have to say that, with few exceptions, there wasn’t a lot of connection between folks that represented those movements who came to New York, or came to the United States, and these Black solidarity groups. It sometimes felt like one hand clapping, in that, I later worked at the American Committee on Africa, a white- led organization, and I would see the leadership there, that if you came to New York and you were coming to the United Nations, you would stop at ACOA and the leaders of these movements and these organizations would commonly come and meet with mostly white folks who were involved in the solidarity movement.

But, it really felt like one hand clapping. Seldom would they meet with these black solidarity groups like African Liberation Support Committee, to be an example. Cabral took the time to connect with us. He came to Harlem, he met with various organizations. He will talk later, probably, about how he wrote to us as well and talked about our struggles, our common struggles. But, he recognized us, in that sense. At a very personal level. And, at an even more personal level, he gave us time. I was 21 years old when all this was happening, when he came here. And, he stopped with me. I mean, he asked me who I was? What did I do? What was my involvement? And everything.

So, he gave me time. He wasn’t such a high-powered person that he couldn’t make that personal contact. So it’s really the personal connection with people and the personal connection with Black Americans that was most striking for me. And, being a simple African man in making that connection, he came across simply. He didn’t come across high power. He just came across directly in that sense. And so, it was a very formative connection, even however brief, that I had with him. That’s how he connected. We’ll talk later about, he connected further by going to Lincoln University and writing to [inaudible 00:13:31] about that, about our common struggles. But, at the personal level, that’s what really stands out for me.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. So I’m going to ask a number of questions. And, since there’s four of you, I’m going to ask you to jump in and not be polite and wait back, or hold back, in the interest of time, if you have a comment or response to the questions. I’m addressing that to everybody. One of the things, in Cabral’s address at Lincoln, he talked about identity. And a lot in the recent past. We hear about identity, identity politics. What did Cabral mean when he was talking about identity? And how does that similar or different from what goes by the notion of identity politics today? Whoever would like to start with that?

Polly Gaster: Okay. Identity very much linked with culture, I think was from Cabral’s point of view. And he was talking more about the identity of a society, of a nation, of a group. He was not talking about individual identities. And he was talking about identity, which stems from history, from experience, from reality. And, I personally feel the current emphasis on individual identity is very dangerous in terms of organizing, in terms of society, because it’s difficult. But, anyway, that’s just me. So that’s what I think that his identity was. I’m sure, Stephanie might not agree.

Stephanie Urdang: I agree. I think that when he was talking about identity in terms of Guinea-Bissaun, it was that people were Guinea-Bissaun. They were not Tula or another [inaudible 00:15:50]. And that people really worked together. And, across the board, there were people from different ethnic groups in different aspects of the revolution. And he was very proud of this. And he felt that he had broken down the divisions, or that was his goal. And the PAIGC’s goal was to break down the divisions that could lead to conflict. And then, if people really identified with who they were and building a country that was theirs, that would be the identity. And, I agree with Polly about not an individual identity, so that you’re in a position to further your own personal politics. But, it was very much a collective.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: I feel very strongly that what Polly and Stephanie have just said are both key components of Cabral’s thinking. But, I think the other part of it was that, along with that strong sense of identity went a strong sense of group identity, that you identified as part of a revolutionary people who, as part of the process of making change, reclaiming that identity, re-getting your history and knowing your history was a critical part of doing that. But, it was doing it in a way that was not assertive. I always was really impressed with the fact that Cabral and all of them, I must say … I think all of the concept leaders, all the leaders of the Portuguese liberation movements particularly, had a very strong sense that they were fighting not to wipe out white people. They were fighting to get rid of a system. And, as part of that, people identified as … Their strength was knowing their own culture and knowing their own history, but also knowing other people’s history and culture.

I think that another strong part of this was that that sense of identity became a toolkit in the struggle. It was something that helped people move forward. You knew your dances, you knew the dances of other groups. You knew poetry, you knew about other struggles. I was always impressed with how much all of those leaders knew the poetry of African Americans. It was very impressive to me, because I was raised in a family with a lot of emphasis on poetry.

Craig Howard: [inaudible 00:19:04] I’m thinking about identity. Again, thinking about the context of that time in Harlem, where there were a broad range of groups providing support to African liberation movements. And it was at a time only a few years afterwards that I remember Stokely Carmichael chanting at a meeting. “We are an African people,” about really the identity of Africans everywhere. Amongst those groups, though, there were a lot groups … And, I almost hate hesitate to use the naming of them, because the naming don’t really capture it. But, there were those that were more African nationalists or Black nationalists who had a greater cultural affinity. They would change their names and they would identify. Those things are important. There was another group who were a little more to the left, if you will, some with Marxist orientations. They identified with Africa also, but they had more of a class sense of why we’re supporting them.

It’s in that context that Cabral’s comments about identity, I think, really struck home, in the sense that … And, I can’t remember. I’m going to paraphrase this, but I can remember seeing him say it, that, yes, we are all African peoples. There was some version of that, and that’s an important part of our identity. But, he said something like, “But that’s not our fault. That’s not something we chose. That’s something that happened as a result of history.” But in his mind, I remember it was, “But, our support for each other, ah, that’s an engagement. That’s a decision we make. That’s something that we’re doing purposely,” that I thought was a perceptive way of coming down on both sides, if you will. It was recognizing the African connection and the cultural connection. But, I saw him as emphasizing the importance of the political connection, the fact that we identify with the African liberation movements, because it’s the right thing to do.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: I think that this issue of identity, I’d like to talk about its relevance today, because with the growth of post-modernism and post-structuralism, we have seen a different interpretation of identity. And, it has always struck me in reading Cabral and some other theorists, that they were making suggestions, assertions, that were relevant way beyond their particular context of struggle. So, it wasn’t just about Guinea-Bissau, and it wasn’t even just about a national liberation struggle, but that there were implications in what was being argued that were quite applicable in other places. And, I’m wondering how you all look at that? Looking at it today in this issue of Cabral’s understanding of identity, and how does it apply today?

Prexy Nesbitt: Working with the young people I’ve worked with recently, it’s very difficult to get them to think out outside of their immediate box, so to speak. And that, they really don’t like doing that. And that, it’s a big change, because I think that the young people particularly, have contained themselves within their own little, material world and have very little desire to know the history of other people, about other people’s struggles, or to struggle. I think they just want to get the goods without struggle. And, it’s a very destructive thing. I find it’s very hard to teach about people like Cabral and Mondlane and Netto and all of the concept leaders of those liberation movements, because the young people today can’t conceive of people thinking broadly and internationally and outside of their immediate material existence.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Polly, you were going to say something?

Polly Gaster: Yeah. Yeah. I was going to say that, I think that what Cabral was writing about, about identity and about culture are extremely timely or relevant to be recirculating it to people who are interested in reading, and who are looking for alternative solutions. But additionally, that don’t forget that Cabral was used to talking all the time in his writings about groups, groups, interest groups. Group of the petty bourgeoisie, the group of the peasants, the group of this. And was talking about how they had the work to be done, how it was to bring those groups with their different interests together into recognizing that fighting for independence was in the interests of all the groups, if I’m making myself clear.

And the international solidarity, I agree with Prexy, that it was an automatic normal consideration for all those leaders, that they were part of a wider international movement, but that was because of their different experience. A lot of them like Cabral studied in Portugal, don’t forget. Did their university student and learned about underground anti-fascist networks and working in cells and resistance. And even within not armed struggles, obviously, Stephanie.

And so I think they took all that with them. And then, when they were building up, they were looking at other countries that were becoming independent before them and so on. And not just in Africa, but looking around Latin America, looking at east and west and [inaudible 00:26:24] to relate. So, I think that he had an idea of groups within the society and the struggle of bringing them together, which is … Well, at the same time, I would agree with Prexy that times have changed. And the important thing when we talk about it, is to try to make a context, I think, because otherwise, even then it’s difficult.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: And Craig, you were talking about, at that point, the splintering in the black freedom movement between what were identified at the time as cultural nationalists, versus revolutionary nationalists and Pan-Africanist, et cetera. And, when you think about what Cabral’s emphasis on culture, think about that. How did it compare or contrast with what many of us meant at the time in the Black freedom movement about culture?

Craig Howard: I can’t say that I remember how we were all thinking of culture then. But, I can only repeat some of what I said earlier, in that the cultural identification was so strong across Black America, as you know, but certainly in Harlem. Harlem was in many of those kind of respects was the capital. The cultural identification with Africa and the rediscovering of the cultural identification was so strong, that I’d say three quarters of these meetings that we would have, they were come dressed as an African, various African clothes. So, it was part of that reawakening and rediscovering, if you will.

Again, I’ll say it again. What I liked was he recognized that, and he honored that, but he also emphasized that it’s not only culture. I think this is the opening to other cultures should be part of this. Other groups of people should be part of this. It’s not only culture, but what’s really important is the political engagement and the decisions we’re making. So again, he struck both of those. And I think it resonated at a time when there was deep ideological struggle among these organizations. But, I think he resolved that contradiction, if you will, favorably, because I think everybody felt like he was speaking to them all. He honored everybody, but he made a clear point that it’s a decision that we make when we’re supporting and [inaudible 00:29:19] struggle. And it shouldn’t be based only on the cultural affinity. It should be based on … I’m not using the Marxist jargon anymore. It should be based on what’s right. And I think that again, is the significance, I think.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Stephanie, one of the things we were talking about before the program started was the role of women in the struggle in Guinea-Bissau, under the leadership of the PAIGC. And, I’m remembering that in rereading Return To The Source, that there were these major breakthroughs that PAIGC was leading in terms of a number of things in Guinea-Bissau. But, one of the most important being the role of women and enhanced role of women in leadership. And, I wondered what your thinking was about that and how important that was to Cabral?

Stephanie Urdang: I remember being at a meeting at Jennifer Davis’ house, where a lot of people had come to listen to him. It was a few months before he was assassinated. And in his talk, he mentioned women, but he didn’t go into it in great detail. And so, I went up to him afterwards and asked him, what is the role of women? Are they active? He got this very proud look on his face. And he took out a package of photographs, and one by one showed them to me, of women being involved in every aspect, from the villages to being in the army.

And he said that women were the easiest to mobilize, because they understood so deeply what change would mean for their life. And so, it was this, and I think actually, he changed my life in reality, because eventually I was invited to visit Guinea-Bissau during the war and liberation. And, I’ve had these thoughts about what Cabral had said and so decided to focus as a journalist on interviewing women and trying to really hear them, hear their stories about what change was taking place.

And, as I traveled through both the south and the eastern front, I spoke to many, many women, from peasants to leaders, to regional leaders to the top leadership. And there was this sense of awe for Cabral, for what he had done in articulating the importance of women as part of the revolution on every single level. And, that mechanisms needed to be in place, because he understood that it wasn’t easy for the men to accept women in many of these roles. And, the phrase that I kept hearing, from one end to the other was that Cabral would say, “We are fighting two colonialisms, one of Portuguese and the other of men.” And they hung onto this.

This was something I heard a lot, and I just saw women on justice tribunals where women on committees in the villages, women in regional positions, women who had to travel from their villages because of this work, and their men, their husbands, were taking over looking after the children. Many women would say it was very hard at first, and that the only way they could often get men involved when they would be working as mobilizers was that they would say, “If you don’t have the courage to join the revolution, then the women will wear the pants and they’re going to come.” And that changed a lot of men’s minds who thought that women were going to go without them. Of course, there were issues and a lot of women talked about that, that their men did not favor what they were doing.

And, I’m sure that many women gave up, but many, many women did not. And they just said basically, “I’m doing this. This is my life. This is our future. This is for our children.” And they understood that in a very deep way, that I never heard expressed by men who would give me the sort of lip service about women, but not all. Some men were very articulate about this, and they’d learned from Cabral. I mean, Cabral had been very emphatic that we can’t have a revolution with half the population. And that women have particular areas in which they’re oppressed and we’ve got to deal with that. And that it’s systemic. And, if we’re changing Guinea-Bissau, and we have a future for our people, women have to be central.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Polly, do you have some thoughts on this that you’d like to add?

Polly Gaster: Yeah. My thought is wondering a little bit away. I’m wondering why the leaders of, or the movement, the liberation movements, the three Portuguese colonies in Africa, have very similar positions on some of these critical issues? And, why we need the Cabral so much is because he wrote he and he sought and he wrote. Whereas Mozambique, FRELIMO, they’d have a big round and a discussion in the central committee meeting and then the policy would come out and that would be … And then ,they’d strive to implement things as in when they created the women’s detachment and so on and MPLA in Angola. And I just wonder if something, I can’t think quite what, something not Anglophone was maybe, I’m not sure. Just a little thought. But, yeah. Who articulated so well these … I mean, they all worked together all the time. But, Cabral articulated best for everyone.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Craig and Prexy, I’m curious, your thoughts?

Prexy Nesbitt: My thought, just jumping off what Polly said, I think that they actually worked together much more than what we often realize. That there was a lot of collaboration that came across and it really came out during the sixth Pan-Africanist Congress in Tanzania, when maybe … Craig, I don’t know if you were there? Or Bill? I wasn’t. I remember Bob Van Lupe and I weren’t allowed to go to that. And I think the part of that was that they didn’t want, quote, “leftist Blacks” from the States to come to that conference.

But, then there was an incredible discussion that took place, much of which was recorded and has not been written enough about, between the leaders of the MPLA, FRELIMO and PAIGC and the African-American delegation that came and some of the West Indians. And, one of the subjects they talked about was the role of ideology, the role of political thought. And, interestingly enough, there is a three-volume book that’s never been reproduced. Maybe it’s something from Monthly Review in the future, I don’t know, that is a collection of all those writings of those leaders.

And one is struck by how much similarity there was in the thinking. And, that that similarity came out of their life experiences, I think. Their working together was a very real undertaking. And it was particularly true of the leaders of the Portuguese colonies. Polly, you can say much more about this, because you worked with the Committee for Freedom in Mozambique and Guinea-Bissau. We didn’t have anything like that, that worked with all of the liberation movements in the United States. And they worked together. There was a lot of exchanging of … And that came out of their lived experience.

Cabral was part of MPLA, wasn’t he, at some point? And then, they had all been in Portugal. They had all been on the run when the Portuguese P-Day forces came after them. So, I think that the lived experience of all of them, led to them having very well- thought-out positions and perspectives.

Polly Gaster: [inaudible 00:39:27] And the PAIGC’s doctor was, Boal was an Angolan. I think he always worked with PAIGC.

Craig Howard: That’s right.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Hold on one quick second, Craig. I want to shift gears a second, to segue off of these last comments, Cabral was killed in early ’73. And, I remember very well when it was announced. And the immediate response by most of us in the left and progressive movements was that he had been assassinated by Portuguese agents. And, that seemed to be the line. But, then it appears that the situation was a little bit more complicated than we had been led to believe, or we … Or, I shouldn’t say, “led to believe,” that we understood. And I’m wondering about the contradictions, not just in PAIGC, but when you mention MPLA and FRELIMO, you have these left led movements. And in the case of MPLA, and you look at it today, as a party of the super rich in Angola, it’s like, “Well, what happened? What are the lessons that we can learn from there?” And, I guess, I just want to start with the assassination of Cabral. And, what we can conclude from what we understand to have happened. And, I will ask you, Craig, if you want to start?

Craig Howard: That’s a tough question. That’s a bigger question that I can answer. But, let me just say, I remember hearing, and this might have been legends, might not have been true, his last words of appealing to … I don’t even remember the person’s name. Was it Barbosa or something? The person that was about to shoot him, and he was pleading with him, “This is not the way that we settle conflicts or that we settle differences and the like.” My reaction to the assassination in that sense is, in many respects, I grew up. If it had been the Portuguese, I could have continued with this view of right and wrong and everything is black and white. But the assassination is really almost a metaphor for Africa and African post-colonial experience. No more rose-colored glasses in the sense of there are these deep differences amongst all these forces. It’s not just a one side or another.

But I took away from that just the recognition that I carry forever, on just the extent to which they’re going to be forces even within these organizations, even within these countries that we’ve now seen. It makes the outcome of some of these countries, including some of the former Portuguese colonies, less surprising to me. I became less idealistic and I think more sober, in the sense of recognizing that there are all kinds of forces at play, and not the most simplest ones that I initially thought.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Mm-hmm. Stephanie? Same question.

Stephanie Urdang: I don’t have that much to answer in terms … I mean, remember very vividly the moment that I heard that Cabral had been assassinated. And it was actually at Margie Marshall’s house where there was a party and [inaudible 00:43:29] called to let us know and that ended the party. But, the assumption was that it had to be the Portuguese. They’d killed Mondlane. This was the Portuguese. And I was very uncomfortable in accepting that there was another view, because it was so easy to just blame it on the Portuguese and move on.

So, I think I struggled with that, if I think back, and said, “Well, it may have been an African, but he was encouraged by the Portuguese.” But later, looking back now, maybe, and later, was the level of deep conflicts with PAIGC and within Guinea-Bissau itself, particularly between different ethnic groups, to understand that this was absolutely possible. And, I think I had that sense of wanting to believe in PAIGC and everything they did in those early day, and then became more reflected, particularly as I began to write about it. So, I think for me it was a process of growth really, of reconsidering possibilities and realities, and not being so idealistic.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Prexy?

Prexy Nesbitt: Well, having been in Dar es Salaam … Well, let me even go further than that. Having been in Dar es Salaam and also having it be so close to the killing of Fred Hampton in Chicago, and seeing the involvement of people of color in both those killings, it ended up being just a tremendous political lesson for me and for other people, I think. I mean, as Polly would remember, very vividly when Eduardo Mondlane was killed, it was a result of a tremendously difficult internal forces, many of whom were Mozambican, that were working at the behest of Portuguese colonialism and P-Day and CIA and everything else. But, they were black people killing their leaders.

And the same thing happened for me very shortly thereafter, when I got back to Chicago, in terms of the death of Fred Hampton. I’ll never forget my father waking me up to that morning when Fred Hampton was killed and he said, “Black folk helped kill that boy.” And I said, “What? How do you know that?” He said, “Because the man that was involved was “Gloves” Davis, and he was known for beating people up with his gloves on, in the black community. He was a black policeman. And, all of that experience deepened. It really affirmed what Cabral had said in so many ways about the nature of the enemy that you would fight in the struggle against colonialism. That it wouldn’t just be based on color.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Polly, on this question?

Polly Gaster: Yes, please. I agree that yeah, Mozambicans were involved in, for instance, in placing the parcel that contained the book bomb that was sent to Eduardo Mondlane [inaudible 00:47:39] And clearly the people who actually shot Cabral were [inaudible 00:47:45] and were PAIGC. But, as with Mondlane, I am inclined to think, so with Cabral. With Mondlane, the Tanzanian police investigated and they found the bomb parts came from a shop in Larenza Marks. I mean, they weren’t local or Russian or Chinese or anything. And I think it is part of the job of the Portuguese colonial region is to … Well, obviously to infiltrate and try … When I was in the liberated areas of Mozambique in 1972, we’ve met some people who just deserted from the Portuguese army. And they were coming to join FRELIMO. And, of course, we as foreign visitors did an interview and then the tape we’d made mysteriously vanished.

And, later on we read about these guys being exposed as infiltrators, as working for the Portuguese. They were still black. And surely that comes back to where I want to go back to the issue of race when we’re talking about PAIGC and the others. Race and class? Race or class? When Cabral was with us in 1971 in London visiting London, we talked about it the night before the meeting. And, because we had made a huge effort to mobilize Black communities and Black organizations to come and listen to him in the big meeting.

And we talked about it and it was the time when it was “black is beautiful,” and so on, which we as whites bought into. Cabral wouldn’t buy into it at all. He just said … And, I swear I heard it with my own ears. He said, “Racism is always opportunism, full stop.” And then when he went to the meeting the next day he spoke … I think this is where he started thinking about the meetings with Black communities in the States, when he was there the next year, because he used some of the same examples of in his speech, “We can be comrades. It’s better to be a comrade.” Because everybody at the time in London was all, “brother” and “brother” and said, “Okay. We’re all brothers, but it’s better to be a comrade,” and so on.

And, that was, had a very strong impact on everybody in meeting hall, including Black British colleagues, friends, mobilizers, activists, whatever. And, they started calling each other “comrade.” And that surely is the basic point. And, it’s how racism and works in Cabral’s ideological thinking, which comes across so often. And it’s again, very important today. I don’t know if I’ve made myself clear. But, anyway.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Mm-hmm. Oh, indeed. So, we’re going to wrap up. And, I’d like each of you to offer some final comments. And I want to just show to the audience the book, which is being published by Monthly Review. Again, it’s being reissued. So, I want to ask each of you the following. You get in an elevator and you have 30 flights. The elevator’s going up 30 flights, and you have to explain to somebody in the elevator why they should read this book. You only have until the elevator gets to the 30th floor. So, Prexy? The door of the elevator just closed. You’re going up, what do you saying?

Prexy Nesbitt: 30 flights? It’s a 30-flight elevator.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: This elevator’s moving man.

Prexy Nesbitt: It’s a speed elevator, not one of those we have in the old Chicago, that you-

Bill Fletcher Jr.: That’s right. That’s right. That’s right.

Prexy Nesbitt: It’s a speedy, speedy elevator.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: That’s right.

Prexy Nesbitt: If I remember what Cabral said at that meeting in London, he said, “When you call me ‘comrade,’ you bestow on me a responsibility and I have a responsibility to you. To say that you’re my brother or my sister, this is just a function of biology and birth. But to say that you are my comrade is to give you a responsibility. And, I have a responsibility to you.” And, I think that’s been totally forgotten today. In this country, in the United States, you can’t possibly even conceive of saying the word “comrade” any longer hardly, except in very limited, very limited circles. But, to talk in terms of responsibilities that people have to each other, they go much deeper than racial coloring or even economic classifications.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Stephanie, you’re in elevator. Why should people read this book? The door has just closed.

Stephanie Urdang: Okay. So presuming somebody’s in there with me, I would say this is probably the greatest man you’ve never heard of. And, if you read this book, you will understand the nature of revolution that is rarely connected to people, and isn’t about anger and putting down and all that we are seeing in America at the moment, in terms of the horrors of a growing fascist regime, very possibly, in the future. But, here you can understand why we need to act, why as individuals we need to act, and as collectives we need to act. And he expresses those thoughts extremely well. It will change your mind about how you think about the world.

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. Craig? You’re in the elevator.

Craig Howard: I was a African Studies major, so that elevator was at Columbia University in the African Studies Department. And so, I would say, “He’s the leading African, he’s [inaudible 00:55:03] African theoretician, but he is a premier theoretician of colonialism and understanding colonialism and anti-colonial struggles from the inside, talking about how the contradictions in these European colonial societies come together in Africa and in Africans, in terms of understanding colonialism.” And then, I would say, “Oh, yeah. He also led a liberation movement and a gorilla army that defeated the Portuguese. And that it not only defeated the Portuguese, but it sent the Portuguese army back to Portugal to overthrow the Portuguese dictatorship that had lasted something like 30 or 40 years. So, he also has that on his resume. That’s who he is.”

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. And Polly, how would you? The elevator door is closing.

Polly Gaster: Yes. Okay. Off we go, up the lift. No power cuts I hope. I would say that to the person who’s in the lift. I’m talking now. I would say that, “There’s a bloke who was born nearly 100 years ago and who astonishingly has quite a lot to say which is interesting to read now. And, that he sets what he was talking about mostly 50 years ago, which is before a lot of people were born. And it’s very interesting to see what people were thinking about then, and what context they’re in, and who were working and prepared to work for doing something, making something different in society, in their country to not just get rid of colonialism, but to build a society of social justice, equality and, of course, wellbeing, we hope. And that was what was why they were aiming to do that.”

I would say that, “The difference between that and today is that everybody who gets into the press nowadays it’s because they’re rich or they’re corrupt or both, of course. And, that they are the world’s leaders, unfortunately. And how we can get on with them.” We’re up to the 25th floor and I would say, “You can actually work out a path, from how to start thinking about it and how to work out what is really going on underneath, and then try and reach some conclusions. I’m not telling you to copy everything that he says in the book. The way he says it is, his idea was that everybody should work out in their own societies how to do things. But his experiences and thoughts really do help.”

Bill Fletcher Jr.: Thank you. Poll Gaster, Craig Howard, Prexy Nesbitt, Stephanie Urdang. I want to thank you each for joining us on The Real News today to talk about this and to celebrate the publication of, the republication of Return To The Source, selected texts of Amilcar Cabral. I want to thank you all for joining us in our program. Take care.

(Bill Fletcher Jr. has been an activist since his teen years and previously served as a senior staff person in the national AFL-CIO; he is the former president of TransAfrica Forum, a senior scholar with the Institute for Policy Studies, and the author of numerous works of fiction and non-fiction. Courtesy: The Real News Network, a nonprofit media organisation. It makes media to inform people about the movements, people, and perspectives that are advancing the cause of a more just, equal, and livable planet.)