Global corporations are colonising India’s retail space through e-commerce and destroying small-scale physical retail and millions of livelihoods.

Walmart entered into India in 2016 with a US$3.3 billion take-over of the online retail start-up Jet.com. This was followed in 2018 with a US$16 billion take-over of India’s largest online retail platform, Flipkart. Today, Walmart and Amazon control almost two thirds of India’s digital retail sector.

Amazon and Walmart have a record of using predatory pricing, deep discounts and other unfair business practices to attract customers to their online platforms. A couple of years ago, those two companies generated sales of over US$3 billion in just six days during Diwali. India’s small retailers reacted by calling for a boycott of online shopping.

If you want to know the eventual fate of India’s local markets and small retailers, look no further than what US Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said in 2019. He stated that Amazon had “destroyed the retail industry across the United States.”

Amazon’s corporate practices

In the US, an investigation by the House Judiciary Committee concluded that Amazon exerts monopoly power over many small- and medium-size businesses. It called for breaking up the company and regulating its online marketplace to ensure that sellers are treated fairly.

Amazon has spied on sellers and appropriated data about their sales, costs and suppliers. It has then used this information to create its own competing versions of their products, often giving its versions superior placement in the search results on its platform.

The Institute for Local Self-Reliance (ILSR) published a revealing document on Amazon in June 2021 that discussed these issues. It also notes that Amazon has been caught using its venture capital fund to invest in start-ups only to steal their ideas and create rival products and services. Moreover, Amazon’s dominance allows it to function as a gatekeeper: retailers and brands must sell on its site to reach much of the online market and changes to Amazon’s search algorithms or selling terms can cause their sales to evaporate overnight.

Amazon also makes it hard for sellers to reduce their dependence on its platform by making their brand identity almost invisible to shoppers and preventing them from building relationships with their customers. The company strictly limits contact between sellers and customers.

According to the ILSR, Amazon compels sellers to buy its warehousing and shipping services, even though many would get a better deal from other providers, and it blocks independent businesses from offering lower prices on other sites. The company also routinely suspends sellers’ accounts and seizes inventories and cash balances.

The Joint Action Committee against Foreign Retail and E-commerce (JACAFRE) was formed to resist the entry of foreign corporations like Walmart and Amazon into India’s e-commerce market. Its members represent more than 100 national groups, including major trade, workers’ and farmers’ organisations.

JACAFRE issued a statement in 2018 on Walmart’s acquisition of Flipkart, arguing that it undermines India’s economic and digital sovereignty and the livelihoods of millions in India. The committee said the deal would lead to Walmart and Amazon dominating India’s e-retail sector. It would also allow them to own India’s key consumer and other economic data, making them the country’s digital overlords, joining the ranks of Google and Facebook.

In January 2021, JACAFRE published an open letter saying that the three new farm laws, passed by parliament in September 2020, centre on enabling and facilitating the unregulated corporatisation of agriculture value chains. This will effectively make farmers and small traders of agricultural produce become subservient to the interests of a few agrifood and e-commerce giants or will eradicate them completely.

Although there was strong resistance to Walmart entering India with its physical stores, online and offline worlds are now merged: e-commerce companies not only control data about consumption but also control data on production and logistics. Through this control, e-commerce platforms can shape much of the physical economy.

What we are witnessing is the deliberate eradication of markets in favour of monopolistic platforms.

Bezos not welcome

Amazon’s move into India encapsulates the unfair fight for space between local and global markets. There is a relative handful of multi-billionaires who own the corporations and platforms. And there are the interests of hundreds of millions of vendors and various small-scale enterprises who are regarded by these rich individuals as mere collateral damage to be displaced in their quest for ever greater profit.

Thanks to the helping hand of various COVID-related lockdowns which devastated small businesses, the wealth of the world’s billionaires increased by $3.9tn (trillion) between 18 March and 31 December 2020. In September 2020, Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s executive chairman, could have paid all 876,000 Amazon employees a $105,000 bonus and still be as wealthy as he was before COVID. Jeff Bezos – his fortune constructed on unprincipled methods that have been well documented in recent years – increased his net wealth by $78.2bn during this period.

Bezos’s plan is clear: the plunder of India and the eradication of millions of small traders and retailers and neighbourhood mom and pop shops.

This is a man with few scruples. After returning from a brief flight to space in July, in a rocket built by his private space company, Bezos said during a news conference:

“I also want to thank every Amazon employee and every Amazon customer because you guys paid for all of this.”

In response, US congresswoman Nydia Velazquez wrote on Twitter:

“While Jeff Bezos is all over the news for paying to go to space, let’s not forget the reality he has created here on Earth.”

She added the hashtag #WealthTaxNow in reference to Amazon’s tax dodging, revealed in numerous reports, not least the May 2021 study ‘The Amazon Method: How to take advantage of the international state system to avoid paying tax’ by Richard Phillips, Senior Research Fellow, Jenaline Pyle, PhD Candidate, and Ronen Palan, Professor of International Political Economy, all based at the University of London.

Little wonder that when Bezos visited India in January 2020, he was hardly welcomed with open arms.

Bezos praised India on Twitter by posting: “Dynamism. Energy. Democracy. #IndianCentury.”

The ruling party’s top man in the BJP foreign affairs department hit back with: “Please tell this to your employees in Washington DC. Otherwise, your charm offensive is likely to be waste of time and money.”

A fitting response, albeit perplexing given the current administration’s proposed sanctioning of the foreign takeover of the economy, not least by the unscrupulous interests that will benefit from the recent farm legislation.

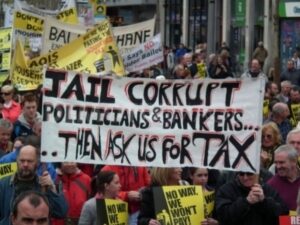

Bezos landed in India on the back of the country’s antitrust regulator initiating a formal investigation of Amazon and with small store owners demonstrating in the streets. The Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) announced that members of its affiliate bodies across the country would stage sit-ins and public rallies in 300 cities in protest.

In a letter to PM Modi, prior to the visit of Bezos, the secretary of the CAIT, General Praveen Khandelwal, claimed that Amazon, like Walmart-owned Flipkart, was an “economic terrorist” due to its predatory pricing that “compelled the closure of thousands of small traders.”

In 2020, Delhi Vyapar Mahasangh (DVM) filed a complaint against Amazon and Flipkart alleging that they favoured certain sellers over others on their platforms by offering them discounted fees and preferential listing. The DVM lobbies to promote the interests of small traders. It also raised concerns about Amazon and Flipkart entering into tie-ups with mobile phone manufacturers to sell phones exclusively on their platforms.

It was argued by DVM that this was anti-competitive behaviour as smaller traders could not purchase and sell these devices. Concerns were also raised over the flash sales and deep discounts offered by e-commerce companies, which could not be matched by small traders.

The CAIT estimates that in 2019 upwards of 50,000 mobile phone retailers were forced out of business by large e-commerce firms.

Amazon’s internal documents, as revealed by Reuters, indicated that Amazon had an indirect ownership stake in a handful of sellers who made up most of the sales on its Indian platform. This is an issue because in India Amazon and Flipkart are legally allowed to function only as neutral platforms that facilitate transactions between third-party sellers and buyers for a fee.

Under investigation

The upshot is that India’s Supreme Court recently ruled that Amazon must face investigation by the Competition Commission of India (CCI) for alleged anti-competitive business practices. The CCI said it would probe the deep discounts, preferential listings and exclusionary tactics that Amazon and Flipkart are alleged to have used to destroy competition.

However, there are powerful forces that have been sitting on their hands as these companies have been running amok.

In August 2021, the CAIT attacked the NITI Aayog (the influential policy commission think tank of the Government of India) for interfering in e-commerce rules proposed by the Consumer Affairs Ministry.

The CAIT said that the think tank clearly seems to be under the pressure and influence of the foreign e-commerce giants.

The president of CAIT, BC Bhartia, stated that it is deeply shocking to see such a callous and indifferent attitude of the NITI Aayog whch have remained a silent spectator for so many years when:

“… the foreign e-commerce giants have circumvented every rule of the FDI policy and blatantly violated and destroyed the retail and e-commerce landscape of the country but have suddenly decided to open their mouth at a time when the proposed e-commerce rules will potentially end the malpractices of the e-commerce companies.”

Of course, money talks and buys influence. In addition to tens of billions of US dollars invested in India by Walmart and Amazon, Facebook invested US$5.5 billion last year in Mukesh Ambani’s Jio Platforms (e-commerce retail). Google has also invested US$4.5 billion.

Since the early 1990s, when India opened up to neoliberal economics, the country has become increasingly dependent on inflows of foreign capital. Policies are being governed by the drive to attract and retain foreign investment and maintain ‘market confidence’ by ceding to the demands of international capital which ride roughshod over democratic principles and the needs of hundreds of millions of ordinary people. ‘Foreign direct investment’ has thus become the holy grail of the Modi-led administration and the NITI Aayog.

The CAIT has urged the Consumer Affairs Ministry to implement the draft consumer protection e-commerce rules at the earliest as they are in the best interest of the consumers as well as the traders of the country.

Meanwhile, the CCI it probably will complete its investigation within two months.

(Colin Todhunter specialises in Development, food and agriculture and is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization in Montreal. Article courtesy: Countercurrents.org.)