Allende’s presidency accelerated a process of political revolution that had begun years earlier. Washington had been worried as early as 1958, when Salvador Allende came within a whisker of winning the presidential election. He lost by less than 3% with candidate Zamorano, who mimicked his programme aiming at taking votes away from him, getting over 3% of the votes cast (41,304 votes). The final results were 389,909 votes for Jorge Alessandri (candidate of the right-wing Conservative and Liberal parties – Chile’s rancid aristocracy) against 356,493 for Salvador Allende, candidate of the FRAP (Popular Action Front, essentially an alliance of Communists and Socialists). Chile’s establishment also fielded Radical Party candidate Luis Bossay (15,5%, 192,077 votes) and US imperialism invested heavily in the Christian Democratic party whose candidate, Eduardo Frei, scored 20,7% of the vote (255,769 votes). In other words, the Chilean bourgeoisie, in cahoots with imperialism, did everything in its power to fragment the popular vote to ensure the Right’s victory. Even so, Allende came close to winning.

The disquiet in Washington did not abate; they knew that Allende’s leadership, steering an alliance of Communists and Socialists, represented a formidable threat to its hegemony in what they deemed a crucial country. Such a political alliance had the potential to reduce, if not eliminate, the politico-electoral fragmentation of the popular forces; it had the real capacity to mount a formidable challenge in the presidential elections of 1964. Washington’s disquiet was substantially heightened by developments in Cuba where a young lawyer, Fidel Castro, had not only ousted US-backed dictator, Fulgencio Batista in 1959; he had also inflicted a humiliating defeat on a US-sponsored military invasion in 1961. He had then accepted Soviet nuclear missiles on the island and had gone as far as to declare the revolution socialist, right under their noses.

So Allende’s closeness to victory in 1958 was managed with manipulation and chicanery, and what Washington had identified as crises or problems in the region were sorted out with swift brutality (Guatemala 1954, for instance); but the challenge posed by Allende in 1964 appeared much more serious given the existence of socialist Cuba and its geopolitical Soviet dimension. So much so that the CIA funded a multimillion-dollar and very aggressive anti-communist propaganda campaign of demonization. Its message was that if Allende won in Chile the presidential palace would be surrounded by Soviet tanks.

The US financed a scare campaign, aimed particularly at women, that if Allende won, the new ‘communist regime’ would take away their children. Additionally, despite massive political differences between the Christian Democrat candidate, Eduardo Frei, and the traditional elite (Liberals and Conservatives, the landowning elite) particularly on the question of carrying out a thoroughgoing land reform, the US managed to persuade the whole elite to fall behind Frei. Frei also offered to ‘Chileanize’ the copper industry, and successfully appealed to the poor that weren’t organised in trade unions (especially shanty town dwellers), a large constituency indeed. These reforms were palatable to the US since they were framed within the context of US President John Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress programme (implement reform to prevent the regional spread of Cuban communism) designed to isolate Fidel’s revolution. The FRAP was outflanked and its propaganda apparatus overwhelmed thus, unsurprisingly, giving Frei a 56.1% (1,409,012 votes) compared to Allende’s 38,9% (977,902).

The failure of Frei’s “Revolution in Liberty” government programme had the double consequence of legitimising structural reforms to society, economy and political system, and breaking the traditional consensus based on the peasantry’s political inactivity. Frei’s land reform saw the tumultuous political awakening of the peasantry whose last ‘revolt’ had taken place back in 1934, involving a small group of farmers in one little community in Lonquimay that was brutally supressed. In contrast, between 1964 and 1970, the number of peasant strikes was 4,815 with 670 land occupations (many were armed occupations). Furthermore, whereas in 1967 there were 211 peasant trade unions organising 47,473 members, by 1970 there were 632 peasant trade unions with 127,782 members. The peasantry had erupted as an explosive and militant social and political force which seriously destabilised the apparently solid democratic Chilean edifice. This cumulative political, social and historic process created the context, which would lead to the election of Salvador Allende as President of Chile.

Chile’s democracy had a long history, notwithstanding being an underdeveloped country. It was in many respects unique in Latin America: elections took place according to the constitutional calendar; all political parties involved respected election results; Communists and Socialists were legal mass parties with strong representation in both Congress and the Senate, and they could and did form part of coalition governments (such as the Popular Front government elected in 1938 that would industrialise the country and that would last until 1947-52); and there was no electoral fraud. In more than one sense, Chile’s democracy resembled pre-1989 Western European democracy. In fact, Allende had been minister of public health in the Popular Front government (1938-42) and before being elected President he was President of the Senate (1967-69). That is to say, Chile’s democracy had expanded so much that it made it possible for a Marxist presidential candidate, propounding a political programme of structural reforms to begin the transition to a socialist society, to be elected.

Allende’s Popular Unity elected to government

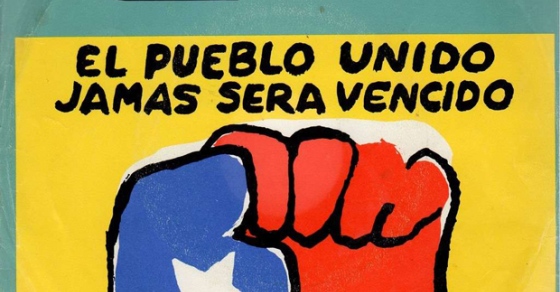

The period leading to the election of Salvador Allende as President of Chile was heavily dominated by an unusual degree of political, artistic, musical and, ideological effervescence. This period saw the rise of Victor Jara, Inti-Illimani and Quilapayún as musicians, writers, poets and singers who gave expression to the pent-up aspirations of workers, peasants, the homeless, the poor, women, and the downtrodden. The dominant themes were: the existing capitalist system is rotten; bourgeois Christian Democracy reformism does not work, is a con and we have had enough; all power to the people.

The politicization of large sections of the population had taken decades, but its socialist radicalization occurred during the Frei administration (1964-70) that saw the rise of artists and radical protest singers such as the Nueva Canción Chilena (New Chilean Song Movement). The terrain for such politicization had been prepared by the unremitting pioneer folkloric music about Chile’s underdog accomplished by Violeta Parra, and by Pablo Neruda’s Latin Americanist poetry in his 1950 Canto General.

In this period the Cantata[1] Santa Maria de Iquique, composed by Luis Advis, that combined classical and folkloric music and mixed songs, lyrics and narrative, symbolised and epitomised the spirit of the period. The Cantata sang the history of a massacre of nitrate miners in the northern city of Iquique in December 1907. It powerfully linked up past proletarian struggles and their aspirations of social redemption with the prospect of realizing them by building a new Chile free from exploitation, inequality and institutionalised violence that would become a reality with the election of Salvador Allende. Quilapayún premiered the Cantata in July 1970 at the second Festival of New Chilean Song, barely months away from the presidential election.

Already in the first Festival of New Chilean Song, held in July 1969, a manifestation of a militant cultural movement aimed explicitly at revolutionising society, Victor Jara had shaken Chile with his winning song ‘Prayer of a Tiller’: in a powerful dialogue with God, a farmer begs to be delivered from those who oppress him and his kind, asks for the barrel of his rifle to be cleaned so His Will on Earth is finally done, and implores God to give him the strength and courage to fight united with his brethren to build the future Chile needs. Jara had already impacted Chile’s politics with songs such as his memorable anti-war Te Recuerdo Amanda, and later on in 1971 with his extraordinary The Right to Live in Peace in homage to Ho Chi Minh and the struggle of the people of Vietnam. It was this inspirational eruption of radical songs that in 1970 led a number of composers to produce the by now globally known and immortal Venceremos, the marching hymn of Popular Unity.[2]

The failure of Frei’s reform programme both strengthened the Left and weakened Chile’s Right which confronted a confident Allende whose popularity was rising whilst theirs was declining. Not only had the Christian Democracy congressional vote declined from 43% in 1965 to 31% in 1969, the party had also suffered two splits from left-wing currents (the Christian Left and the MAPU) that joined the Popular Unity coalition. Furthermore, Allende’s standing had massively increased when in 1968 he showed he had the courage of his convictions and was prepared, in his capacity as President of Chile’s Senate, to personally accompany the survivors of Che’s guerrillas in Bolivia on a long and convoluted trip back to Cuba. He visited them as detainees in Iquique after they crossed into Chile from Bolivia, where they requested political asylum. This unadulterated courage was a personal trait that marked Allende out from other, moderate politicians who promoted the strategy of a peaceful socialist revolution.

Given this context, the chances of the Left led by Allende winning the 1970 presidential elections grew by the day. This led Chile’s Right and US imperialism to resort to their full arsenal of dirty tricks, to mobilise all social and political forces they could and to deploy all their assets. The CIA bankrolled Christian Democracy to try and prevent more members leaning towards Allende – there was particular concern about a potential collaboration between Christian Democrat candidate, Radomiro Tomic, and Popular Unity. They ensured there was a Tomic candidacy whose election manifesto was – rhetorically – at least as radical as Popular Unity’s so as to fragment the popular vote and thus deny Allende an absolute majority. Simultaneously they sought the victory of the traditional right-wing candidate and ex-president, Jorge Alessandri. For good measure, the CIA (as in the 1964 election) launched a massive scare campaign, about which the Church Commission’s report (Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973, Select Committee US Senate, 1975, p. 22) stated:

There was a wide variety of propaganda products: a newsletter mailed to approximately two thousand journalists, academicians, politicians, and other opinion makers; a booklet showing what life would be like if Allende won the presidential election; translation and distribution of chronicles of opposition to the Soviet regime; poster distribution and sign-painting teams. The sign-painting teams had instructions to paint the slogan “su paredón” (execution wall) on 2,000 walls, evoking an image of communist firing squads. The “scare campaign” (campaña del terror) exploited the violence of the invasion of Czechoslovakia with large photographs of Prague and of tanks in downtown Santiago. Other posters, resembling those used in 1964, portrayed Cuban political prisoners before the firing squad, and warned that an Allende victory would mean the end of religion and family life in Chile.

Additionally, El Mercurio, one of the most influential Latin American newspapers, “enabled the (local CIA) Station to generate more than one editorial per day based on CIA guidance.” “According to the CIA, partial returns showed that 726 articles, broadcasts, editorials, and similar items directly resulted from Agency activity (placed in the Latin American and European media).” This was part of the “propaganda mounted during the six-week interim period (between Allende’s election and his inauguration).” (Church Commission, pp. 22, 25)

Despite all these efforts, Allende won the election with 1,070,334 votes (36,6%), Alessandri got 1,031,159 votes (35.3%) and Tomic 821,801 votes (28.1%). That is, the percentage in favour of the radical transformation of Chile was nearly two thirds compared to those in favour of the status quo. On the dawn of September 5th once the victory had been confirmed, tens of thousands of Allende and Tomic supporters joined together in the streets to celebrate the defeat of the Right.

Democracy, the obstacle to stop Allende

As soon as the 1970 electoral results were announced, US imperialism activated Track I of their plan to prevent Allende from becoming the constitutional president of Chile. Given that Allende had won a plurality of the popular vote, the constitution demanded that he was confirmed by the joint meeting of Parliament (Congress and Senate – normally a mere formality). The US gambit involved inducing sufficient parliamentarians from Christian Democracy to elect Alessandri over Allende with the proviso that Alessandri would immediately resign, thus creating the legal conditions for a special election in which Eduardo Frei could be legally a presidential candidate. US taxpayers’ dollars (officially US$250,000 to be handled by US Ambassador Korry) were allocated to bribe Chilean parliamentarians to swing behind Alessandri. A variation on this plan was the mass resignation of the cabinet and its replacement with a military cabinet. This US effort to prevent Chile’s democratic will being respected, failed.

US President Richard Nixon then launched Track II on September 15th 1970, instructing the CIA to organize a coup d’état in Chile. The CIA engaged in intense contact with key military and police officers who were willing to mount a coup but were deemed unable to carry one out without the support of the armed institutions. Among those contacted was General Camilo Valenzuela, in charge of the Santiago garrison, and General Vicente Huerta, a senior police officer. The CIA also subsidised and supported the recently formed fascist organization, Patria y Libertad. But the plans did not take off because institutionally Chile’s armed forces were strongly ‘constitutionalists’, that is, they would not act unconstitutionally by staging a coup. This stance was sturdily held by the Commander in Chief, René Schneider Chereau (known as the “Schneider Doctrine”). The plotters, the CIA and Nixon and his advisers, especially Henry Kissinger, drew the conclusion that Schneider would have to be removed so that a coup could unfold. The CIA authorized the kidnapping of Schneider and through diplomatic luggage supplied the weapons.

The incumbent government through its minister of economics, Andrés Zaldívar, went on national radio and TV on 23rd September to announce that as a consequence of Allende’s victory, the economy had suffered severe changes that jeopardised the country’s existing economic normality. It was sufficient to generate financial panic and a serious run on the national currency, leading thousands of ordinary middle class Chileans to queue up in banks to withdraw their savings. The intention was to create a financial crisis that would contribute to the success of the ongoing US-led coup plot.

According to CIA reports, the plan was that once abducted, Schneider would be flown to Argentina, whilst simultaneously Frei would resign and leave the county, and so would his cabinet, then a junta led by a general would dissolve parliament. On 22nd October, a small group of armed men ambushed General Schneider whilst on his to work. In self-defence he drew his official weapon and was shot by the attackers. He died on 25th October on the operation table, two days before Allende was actually confirmed. Thus Track II and the planned military coup also failed. And so Allende was inaugurated on 3rd November 1970, after seven very agitated weeks.

The Allende government, a crucible for mass political participation

Many of us were very active during the election campaign by setting up or joining the tens of thousands of Popular Unity Committees (CUPs) that sprang up throughout the nation, taking to the streets to march for the people’s victory, going out at nights to do graffiti and other propaganda for Allende and tensing our spirits and psyches throughout the difficult passage from a government of the old regime to the establishment of the ‘government of the people.’ We knew it would be difficult, but we had been radicalised by the recent struggles and our impetus had been galvanised by the inspirational culture that had engulfed us in the previous decade. Millions of us would get deeply involved in taking our destiny in our own hands, hourly, daily, for three intense years.

During that period, we made it impossible for the ruling class to continue to rule in the old way, but we would not, despite strenuous efforts, succeed in imposing our own political power. Though the old system was moribund it refused to die, thus the new could not be born. A classic revolutionary situation, with the novelty that the downtrodden had elected their own government.

On election day, we were glued to the radio (a TV set was not yet a feature of every household), waiting for the results. It had been an intense and exhausting election campaign and, ironically on election day, thousands of us, who had worked so hard for Allende and Popular Unity, realized we could not vote because the law deemed us to be minors. By about midnight, suddenly the news stopped broadcasting the results for a long, tense, amount of time, so we knew we had won, but was the silence an ominous sign of a coup d’état? Then suddenly again, the broadcasts continue with Allende’s victory and we exploded in joy hugging our loved ones and taking immediately to the streets to celebrate and to defend the triumph from the sinister and powerful forces operating in the shadows.

Popular Unity’s programme was simple but contained robust structural transformations that had revolutionary implications, a feature the Chilean bourgeoisie and US imperialism fully understood. So did the mass movement supporting it. The programme involved the building of a popular state and a planned economy, most of it state owned, including key banks; the deepening of the land reform begun by Christian Democracy so as to liquidate the scourge of the latifundia system, identified as a major obstacle to both the nation’s development and the wellbeing of millions of rural and urban poor; and the nationalization of the copper mining industry, Chile’s main foreign revenue earner, up to then in the hands of US multinational companies. Although it was to be accomplished through legal and parliamentary reform, it was the most ambitious programme of social, political and economic transformation ever attempted in the country’s history.

The election of Allende to the presidency led to an extraordinary and unprecedented surge of popular participation in politics: people, through tens of thousands of every type of existing social organization (trade unions, neighbourhood committees, etc.) or through ad hoc bodies created for specific objectives (Popular Unity Committees, factory committees, local councils, regional committees, peasant unions, and such like) realized that their government was a decisive factor in the progressive transformation of Chile, they also understood that they had to take their destiny into their own hands and carry out Chile’s socialist transformation themselves.

Allende had no difficulty in expropriating 4,000 large farms, completing in this way the end of the latifundia system but he was also compelled to expropriate 2,000 additional farms because of their militant occupation by peasant organisations that demanded it. This was dictated by the logical dynamics of the process of land reform initiated by Christian Democracy; up to literally 1967, Chile’s peasantry had been kept in conditions of semi-servitude and the substantial democratic gains obtained by militant struggle had exclusively benefited the urban sector.

The levels of peasant self-organisation confirm this: in 1965 there were only 32 unions with a total of 2,118 members in the countryside. This increased to 580 peasant unions in 1970 (the end of the Christian Democratic government) affiliating a total of 143,142 members. This trend intensified under Allende since by 1973 the total number of peasant unions was 881, affiliating 313,700 members, reaching a rate of almost 100% unionisation in the Chilean countryside. The gigantic surge in unionisation and the very militant actions undertaken by the peasantry amounted to a peasant revolution. The key difference with Christian Democracy’s land reform was the level of ferocious repression inflicted on the militant peasant movement, whereas Allende never resorted to state repression of the peasantry’s revolutionary activity. (Rodrigo Medel, Movimiento Sindicalista Campesino en Chile, 1942-2000, CIPSTRA N 2, June 2013, pp. 8-9)

The urban working class underwent a similar process of self-organisation and unprecedented militancy, though it had had a long and strong trade union tradition, first in the Chilean Workers’ Federation (FOCH in its Spanish acronym) founded in 1909 by the revered and iconic Luis Emilio Recabarren, who was also the founder of Chile’s Communist Party. Recabarren also achieved the feat of affiliating the FOCH to the communist-led Red International of Labour Unions. By 1960, vigorous trade union militancy especially among public sector workers (health, education, etc.) had achieved the unionisation of 10% of all workers, a figure that went up substantially, proportionately with militant strike action in opposition to the Christian Democratic government, reaching about 24% in 1970 and jumping to nearly 34% in 1973 under Allende, the highest ever in Chile’s history (Tasa de Sindicalización Efectiva (1960-2013), Fundación Sol, http://www.fundacionsol.cl/graficos/tasa-de-sindicalizacion-1960-2013/)

As with its agrarian programme, the Popular Unity government had almost no difficulty in implementing the programme of nationalisation of monopolies, industry, banks and US imperialist industry. The Law of Nationalization of the Copper industry was passed by Congress without opposition, but Allende applied a calculation to deduct excess profits from the compensation to the US multinationals, which resulted in them being told they owed money to the Chilean State. Since the government did not enjoy a parliamentary majority, it resorted to a forgotten law promulgated during a short-lived Socialist Republic in 1932, which endowed the government with the power to expropriate all large Chilean companies. The government also resorted to purchasing shares of the companies to be expropriated thus becoming the main shareholder thereby gaining control over them. Prior to being expropriated by Allende many of these companies were occupied by their workers. In this way, the government managed to get control over 80% of the large Chilean companies and a number of key banks.

Faced with such an onslaught, Chile’s bourgeoisie and US imperialism resorted to destroying and blockading the economy, mobilising petty bourgeois forces to oppose ‘communism’, together with a systematic campaign of terror. Nixon gave the order to make the Chilean economy scream, the purpose of which – as with Venezuela today – was to punish the poorest. By punishing Allende’s social, political and electoral base, the intention was to create the conditions for the overthrow of the government as a precondition to cleansing the nation of the ‘scourge of Marxism’. To engineer economic aggression the US threw into the market large amounts of its own reserves of copper making the price fall, thus denying Chile the bonanza of high world prices for this metal caused by the war in Vietnam.

Chile was then subjected to a savage programme of violent destabilisation, economic hardship, aggression, and civil disobedience. It would not have been possible if the traditional right had undertaken it by itself. However, Christian Democracy had sufficient social bases to give this “regime change” effort a mass character. Transport stoppages created dislocation and chaos. The extreme right had the support of the medical profession whose strikes caused havoc among the poor (I witnessed this in person when I was a shop steward in FENATS, the health workers trade union). But perhaps the worst aspect of the destabilisation plan, exactly as it is with Venezuela today, was the hoarding of foodstuffs and basic necessities by the privately owned retail sector, forcing people, particularly women to queue up for hours on end to purchase ordinary items for daily consumption by their families. This torment was compounded by the deliberate rise in prices to hyperinflation levels, causing economic devastation and huge hardship among the poorest. The people responded with the Juntas de Abastecimientos y Precios (Committees of Supply and Prices – JAP in its Spanish acronym) seeking to ensure the supply of basic necessities and foodstuffs to the poor.

The levels of popular resistance to the US-led onslaught and Allende’s refusal to capitulate, persuaded Washington to deal a killer below by staging a general strike in 1972 – Paro de Octubre – mainly though a national stoppage of truck drivers, heavily financed with millions of Washington’s dollars. It was supported by professional associations (doctors mainly), retail shops, and some student bodies (principally right-wing university students). Given the geographical shape of the country, it was clear that a transport stoppage would have devastating logistic and economic consequences, with the real intention being to bring the country to a halt. The Paro de Octubre formed part of the CIA Track II plan which among other things involved substantial financing of the fascist shock group Patria y Libertad.

In response, public and private sector workers occupied their workplaces and made them function throughout the country in a show of force that stunned the bourgeoisie and imperialism. And though facing tremendous odds they managed to keep most things flowing, supplying hospitals and workers’ canteens as well as communities, where the salient feature was spontaneous self-organization and the setting up of ad hoc committees to deal with the emergency created by the transport stoppage. The instances of sacrifice, commitment and heroism during this period were legendary. The resilience and resistance of the working class and its allies, the poor in urban and rural communities, plus hundreds of thousands of women swelling the JAP ranks contributed decisively to defeat the Paro.

The most worrying feature of the outcome for US imperialism and the Chilean elite was the determined decision by the workers who had occupied hundreds of enterprises not to return them once the stoppage was over. Worse, workers resisted and opposed efforts from some UP leaders to return them to their original owners and took to the streets to demonstrate against such a conciliatory move with the Paro de Octubre golpistas. As it happened, the government announced officially that none of them would be returned. A Socialist Party editorial stated that in the 30 days of Paro, Chile’s working class had learned more than in the previous 36 years of struggle. Another newspaper article registered that in the ‘social economy’ (state-owned or state-controlled) could be found 100% of steel making, 90% of banking, all of the nitrate, iron an copper extraction, 85% of textile production, 70% of all foundries and metallurgy, and 95% of domestic appliances. It added that the 90 large companies that the government owned or controlled were responsible for 60% of all manufacturing.

The US-led destabilisation plan was causing huge difficulties, but it was not producing the desired results: popular support for Allende and the government remained strong and looked like becoming even stronger. US calculations were that the parliamentary elections scheduled for March 1973 would give right-wing parties an absolute majority in Congress with which to impeach Allende, an attainable objective since they had the complicity of Chile’s reactionary judiciary and the support of the Catholic Church. Frei popularised this by depicting the coming election as a plebiscite on Allende’s government in preparation for what they believe to be a crushing defeat for the Popular Unity coalition, blaming all the country’s problems on the very existence of the Allende government. The results came as a shock: the Popular Unity coalition increased their percentage of the vote to 43%, surpassing the 36% that saw Allende elected in September 1970. Paradoxically, the favourable election result for Allende was going to seal its fate: Christian Democracy moved sharply to support the line of Chile’s extreme right and US imperialism – a coup d’état became an absolute necessity.

The rest is well known. On 11th September 1973, Pinochet led the armed forces in a coup that ordered Hawker Hunters to bomb the presidential palace in the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende, events during which he was murdered; the coup led to the establishment of a murderous dictatorship that sought to brutally eradicate any trace of Marxism or socialism in Chilean society.

Conclusion

For millions of us, the Allende years have remained indelibly imprinted on our hearts, memory and consciousness. Never before had the nation seen so much independent political activity by so many for so long, myself included. In the context of the revolutionary process unleashed with the election of Salvador Allende, independent political activity meant taking the country’s destiny into your hands at whatever level you happen to be, something I experienced personally very intensely. One of the memories I have is the sense of not having slept for three years.

Youngsters like myself found ourselves catapulted into the centre stage of politics in the maelstrom years of 1970-1973. At first, we were deeply inspired and politicized by the messages of rebellion spread by the protest song movement, the opposition to the timid reformism of the Christian Democratic government and its failure to deliver on their promise of structural reform.

Then above all, we were inspired by Popular Unity’s promise of the socialist transformation of our country, but we were particularly stimulated, fired and galvanized by the fact we were doing the transforming ourselves. Never before had we heard so many educational and rousing speeches from so many, such as old experienced trade unionists about decades of past struggles; articulate parliamentarians on complex constitutional and political issues; competent cadre imparting fascinating political education talks; barrio female and male leaders on defending their communities and organising the supply of basic necessities to their members; beardless secondary school activists and uniformed school women expressing boundless optimism on the commitment of youth to the struggle for socialism; peasant leaders growling their determination to finish with landownership and landowners; and so much more, every single day. They exuded generosity and self-sacrifice, being prepared to give everything, including their lives, for the socialist cause. The richness and fullness of those years made you wish for the next day to come because there was so much to be done.

The Popular Unity government set up a state publishing house, Editorial Quimantú that produced the most wonderful volumes of world politics, history, philosophy and literature that I had come across first as a young student and then as a trade unionist. How could a young person forget Carlos Luis Fallas’ Mamita Yunai (about the United Fruit crimes in Guatemala) or John Reed’s Ten Days that Shook the World, or the weekly mini-book among which, I vividly remember H.G. Wells’ The Country of the Blind? We read literally volumes in that short historic period. I was so busy with politics and went back home usually at dawn or not at all, that I made a deal with my local kiosk: they kept a copy of the mini-book which I’d collect and pay for at some point during the week; it was the only way since the mini-book would sell out barely hours after distribution.

Editorial Quimantú was originally the Zig-Zag privately owned publishing house, taken over by the workers after a conflict with the owners in 1970. They demanded that Allende expropriate it and for three years its workers ran it, during which time it published 11 million books, from about 250 authors, with every mini-book title selling between 50,000 and 80,000 copies. Some editions such as Popular Education Notebooks (Marxist political education) sold 100,000 copies each, and some even sold 250,000 copies. The books were well-designed, attractive, and above all, very cheap. I do not know where we found the time to read so much, but we did and in large quantities, enhancing our consciousness and commitment. Revolutions, despite the unavoidable imperialist punitive brutal aggression and the concomitant sacrifices they entail, are in more than one sense wonderful historic episodes.

Allende’s years continue to resonate today because of the promise of a new, better, socialist Chile, a nation without oppression, capitalist exploitation or imperialist domination. A society of conscious, active, cultured citizens. Despite all the odds they faced during the Popular Unity government, the masses in Chile resisted horrific US economic and political aggression, US-financed domestic destabilisation, and terrorism because they hung on to that promise, they held on to that dream. The experiment, whatever its shortcomings, did not fail. It was crushed with utter brutality. The dream has never died and it never will, and it is with elation that I register the fact that one of the emblematic songs of the 2019 rebellion against neoliberalism in Chile, was Víctor Jara’s El Derecho de Vivir en Paz, from 50 years ago. What we attempted back in 1970-73 is inspiring them today, thus making it so much more worthy to have tried.

Venceremos! (We will win!)

Notes

1. A cantata (literally “sung”) is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

2. A book by Victor Jara’s wife charts the extraordinary cultural revolution that these young and vibrant musicians, poets and singers brought to an increasingly assertive popular movement for revolutionary change (Joan Jara, Victor: An Unfinished Song, Jonathan Cape Ltd – I would challenge anybody on the left to read it and not to choke with intense emotion).

(Francisco Dominguez, a former refugee from Chile in the UK, is Head of the Centre for Brazilian and Latin American Studies at Middlesex University, London, United Kingdom.)