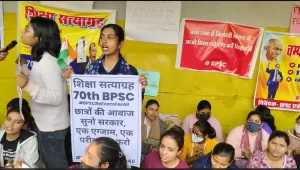

Here is an overview of inequalities in wealth and income in the world in 2021. Unsurprisingly global inequalities in wealth are deeper than inequalities in income. The richest 1% own 38% of the world’s wealth, more than the least wealthy 90% of the population. In other words, 80 million people have far more wealth than 7.2 billion people. The richest 10% concentrate three quarters of the wealth. This is indecent.

Figure 1: Global income and wealth inequality, 2021

Interpretation: Worldwide, 50% captures 8.5% of total income measured at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). The bottom 50% owns 2% of wealth (at PPP). The top 10% owns 76% of total household wealth and captures 52% of total income in 2021. Note that top wealth holders are not necessarily top income holders. Income is after pension and unemployment benefits are received by individuals, and before taxes and transfers. Sources and series: wir2022.wid.world/methodology

In this context, the dominant neo-liberal ideology is pushing for the withdrawal of a State that is often the last bulwark against the widening gap between the richest 1% and the rest of the population. The clear trend since the 1980s towards dismantling the protective role of the State is increasing, reinforcing inequalities in wealth and income, gender inequalities, racial discrimination and so on.

The withdrawal of the State and the increase of private debt

The State’s withdrawal can be seen in a number of ways such as privatizations, cuts in progressive taxes, lower taxes on big business, cuts in public budgets for education and health. These neo-liberal policies are being implemented by the vast majority of governments. In Europe, they are also dictated by the European Union treaties limiting the deficit and public debt in each member country. In the South the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the Development Banks impose neo-liberal conditions on governments, often in complicity with them, in exchange for loans.

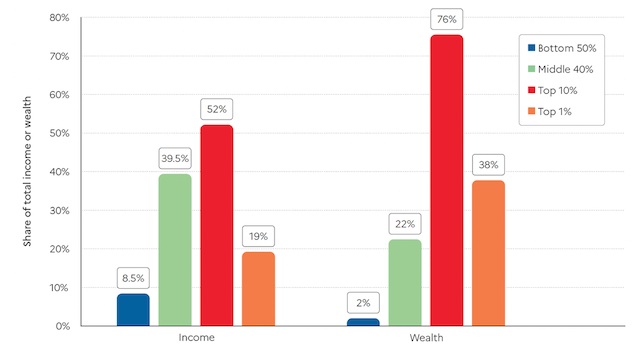

Figure 2: Increase in private wealth vs decrease of public wealth

in countries of the North, 1970 – 2020

Sources and series: wir2022.wid.world/methodology, Bauluz et al. (2021) and updates

Figure 2 clearly shows how the State gets poorer and the private sector gets ever richer in countries of the North. In the six countries shown in the figure (Spain, United Kingdom, Japan, France, Germany and the United States), the same trends have been observed since the mid-1970s: a decline in public wealth relative to national income; and an increase in private wealth, also relative to national income. This decline accelerated in the 2010s, under the impact of the austerity policies introduced after the financial crisis of 2007-2008, which were synonymous with privatization and the sale of public assets. What’s more, the tax cuts on the richest and biggest companies, which have been underway for several decades in the North, are reducing State resources on the one hand and increasing private wealth on the other.

Because they have radically reduced taxation of the wealthiest since the 1970s-1980s, States have become poorer, reducing their capacity for action. Institutions like the IMF and the World Bank encourage the governments of the South in particular to lower taxation of big companies while simultaneously increasing Value-Added Tax. VAT is deeply unfair as it hits everyone with the same percentage, thus disproportionately affecting the poorest who have to spend their entire income on consumption.

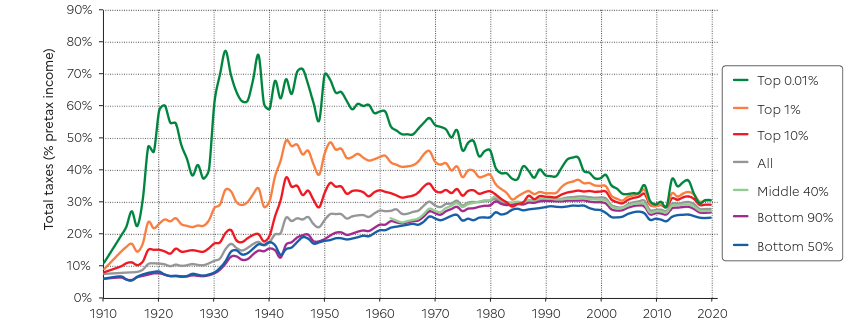

Figure 3 highlights this development in the US. In the 1930s, the top tranche of the income of the richest 0.01% was taxed at a rate of almost 80% but by 2020, only at 30%. The richest 1% paid 50% tax in the early 1950s, before the tax rate dived to 30% for them as well today. The rate of income taxation for the richest 10% has also fallen between 1942 and the present day, by about 5 percentage points.

Conversely, in the United States since the 1930s, the rate of income tax for the poorest 50% has climbed from 8% to about 25%. If we extend the focus to the poorest 90% the trend continues in the same direction.

While income taxation really was progressive from the 1920s until the 1970s, today all income brackets are taxed at very similar rates. This is a general tendency worldwide, concerning not only the United States but all the Western countries as well as the countries of the South under pressure from the International Financial Institutions.

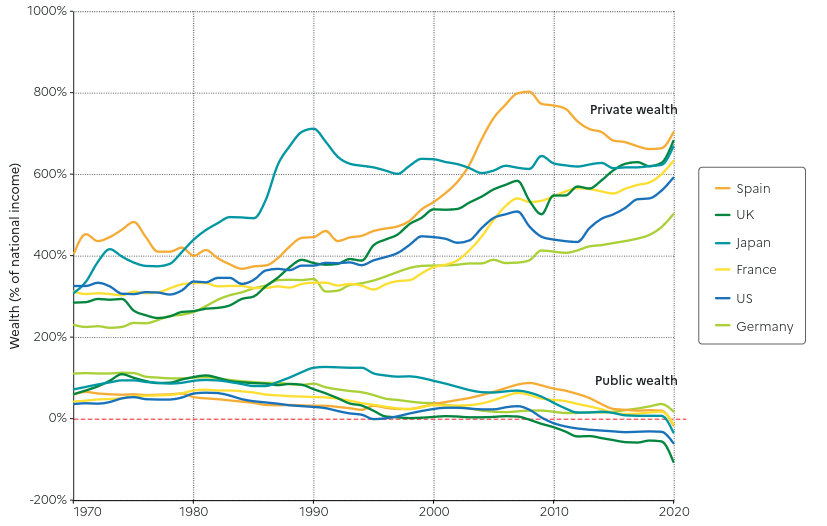

Figure 3: Progressive income tax rates across the world, 1900-2021

Sources: wir2022.wid.world/methodology, adapted from Saez Zucman (2019).

Figure 4: Total taxes paid by income group in the US. 1910-2020

Sources and series: wir2022.wid.world/methodology and Piketty (2021).

Figure 4 focuses on the highest marginal tax rates, i.e. to the rate applying to the higher income brackets. Here too the trend is clear. Tax rates on higher incomes increased until the mid-1940s, notably to finance the war effort (as should now be done for the ecological transition). It then decreases before going up again until the mid-1970s. Since then, in all six countries considered (Japan, France, the UK, Germany, the US and India), tax rates for higher incomes have clearly plummeted. In Japan, they dived from 75% to 37% in 2005, before going up again. In France, higher incomes used to be taxed at a 70% rate in the early 1980s and were taxed at 53% in 2020. In the UK, the marginal tax rate for the highest incomes came close to 100% at the end of the 1970s (!), dropping to 40% by the late 2000s. The drastic fall in taxation of the richest under Margaret Thatcher is impressive. The tendency in the US was similar, with a drop from 92% to less than 40% for the marginal tax rate between 1955 and 2020, particularly under Reagan’s policies. India, the only country of the Global South represented on this graph, has followed a tendency close to that of the United Kingdom and the United States.

This decline of the State has increased private indebtedness, as people previously supported by the State are obliged to compensate for its withdrawal by entering the vicious circle of indebtedness. In the countries of the South, microcredit – principally used by women – plunges them into the inferno of unpayable debt with rates that can go from 20% to 200%, and unacceptable means of bringing pressure to bear when they cannot pay. Promoted by international financial institutions such as the World Bank, microfinance is king. This is illustrated by the fact that many national legislations (such as that of Sri Lanka) forbid the practices of community solidarity lending, and now only allow recourse to microcredit institutions.

In the North, State benefits for the poorest often partly consist of consumer credits which plunge populations, there again, into spirals of indebtedness.

The decline of the State and the concomitant recourse to private indebtedness lead to ever greater wealth for the lenders– that is, the rich – banks, investment funds – through the payment of interest. We are gradually evolving from a system where the State redistributed wealth from the richest to the poorest through welfare benefits and the funding of public services, to a system where inequality is bound to grow and grow, since it enriches the richest and condemns the popular classes to borrowing money from them and paying them interest in order to survive.

This decline of the State exacerbates gaping inequality. Concentration of capital and income, unequal access to employment, hunger and extreme poverty around the world: such outrageous realities cannot be tolerated.

[Maxime Perriot is with CADTM Belgique. The Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM) is an international network of activists founded on 15 March 1990 in Belgium that campaigns for the cancellation of debts in developing countries and for “the creation of a world respectful of people’s fundamental rights, needs and liberties”.]