David Ruccio

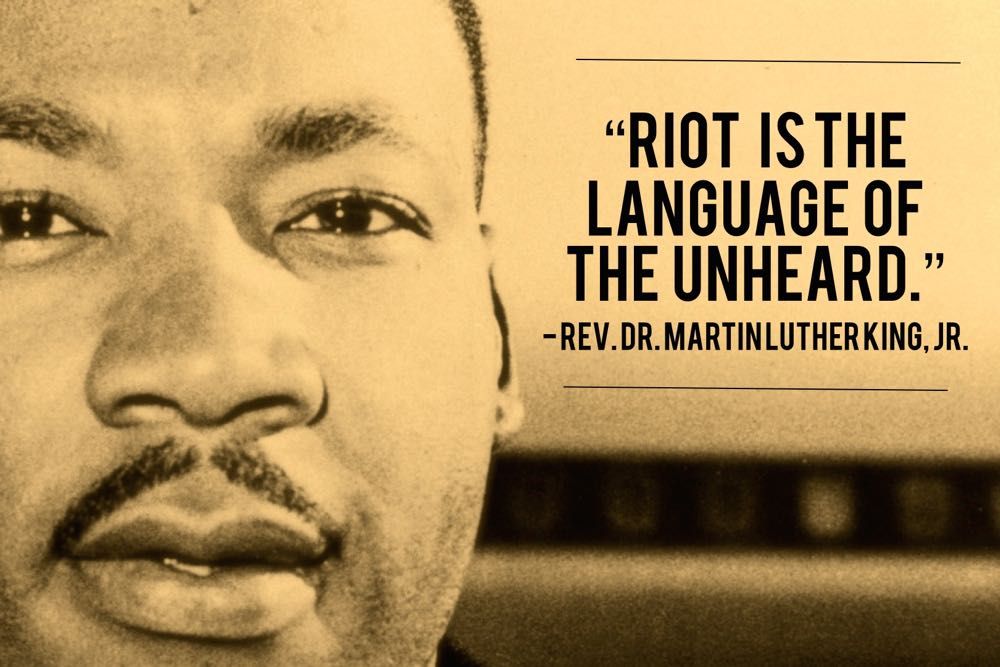

More than 50 years ago (on 14 April 1967), Martin Luther King Jr. delivered one of his famous speeches, on “The Other America,” at Stanford University. King patiently explained to the audience of students and faculty members that, while in his view “riots are socially destructive and self-defeating,” they are “in the final analysis. . .the language of the unheard.”

Today, as protestors take to the streets across America, in response to the recent murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor, King’s words speak louder than ever. America, he warned, “has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met” and that “large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity.”

The question is, what if anything has changed over the past half century?

In the late 1960s, King spent his time focusing on the key economic and social problems of his time. He began with inequality, the existence of “two Americas”—one America that “is overflowing with the milk of prosperity and the honey of opportunity” and another America that “has a daily ugliness about it that constantly transforms the ebulliency of hope into the fatigue of despair.” Therefore, he argued, the struggle for civil rights had to change, from eliminating “legal, overt segregation” to demanding “genuine equality.” The new civil rights movement he envisioned had to recognize the fact that black Americans were facing a depression in their everyday lives—of unemployment, segregated schools, housing discrimination, urban slums, and much else—“that is more staggering than the depression of the [19]30s.” Therefore, he worried,

“All of our cities are potentially powder kegs as a result of the continued existence of these conditions. Many in moments of anger, many in moments of deep bitterness engage in riots.”

King proposed, among other measures, a federal law dealing with the “administration of justice” (after the murders of more than 50 black and white civil rights workers) as well as a “guaranteed minimum income for all people”—which, he explained, the country could afford if “we can spend $35 billion a year to fight an ill-considered war in Vietnam, and $20 billion to put a man on the moon.”

The parallels with the situation today in the United States today are obvious—from the billions spent on Elon Musk’s SpaceX flight to the international space station (the company is currently valued at a whopping $36 billion) through an economic depression reminiscent of the 1930s to the unequal administration of justice that persists almost six years after Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri. And, of course, the point on which King was far ahead of his time, in calling for a guaranteed national income, which Silicon Valley today has the temerity to think it invented.

Right now, black Americans are disproportionately suffering the ravages of both the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic crisis that has accompanied it—in terms of confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths (according to the APM Research Lab) as well as escalating unemployment and being forced to commute to and work in the precarious conditions of “essential” jobs.

Black men and women are also suffering much more than their share of the general population from the continued violence meted out by the nation’s police forces, which has continued unabated since Ferguson. According to the statistics gathered by Mapping Police Violence, black people are three times more likely to be killed than white people in the United States.

The only conclusion we can draw, in 2020, is that the United States represents a failed economic and social experiment. It has failed to deliver economic justice and it has failed to deliver social justice, not only for black people, but for all working-class people—black, brown, and white. It’s based on an economic system that, from the very beginning, has been predicated on disciplining and punishing the bodies of black slaves and, later, of a multiracial working-class, in the pursuit of profits for a tiny group at the top. It has utilized both cultural institutions and state violence to enforce ignorance of and consent to discriminatory practices and obscene levels of inequality. It has made grand promises—of freedom, democracy, and “just deserts”—and, especially in recent decades, it has failed to deliver on them.

Fortunately, at the same time, there are some glimmers of hope. There is a new generation of remarkable activists (such as Black Lives Matter, which grew out of the Ferguson uprising, and the Poor People’s Campaign) and critical thinkers (including Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and Cornel West).

Meanwhile, the participation of many young white people in the demonstrations and protests that have erupted in cities across the country, alongside their black and brown counterparts, is reminiscent of the conditions that caused King not to give up the struggle back in 1967:

“I realize and understand the discontent and the agony and the disappointment and even the bitterness of those who feel that whites in America cannot be trusted. And I would be the first to say that there are all too many who are still guided by the racist ethos. And I am still convinced that there are still many white persons of good will. And I’m happy to say that I see them every day in the student generation who cherish democratic principles and justice above principle, and who will stick with the cause of justice and the cause of Civil Rights and the cause of peace throughout the days ahead. And so I refuse to despair.”

(David Ruccio used to teach in the Department of Economics at the University of Notre Dame. He is currently Faculty Fellow of the Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.)