South Africa has many moments in its long history of struggle that are recognised internationally as turning points. These include the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the Soweto uprising in 1976 and Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990.

Sharpeville marked the turn to armed struggle and the beginning of a new period of repression with the banning of the PAC and ANC. Soweto opened a new period of struggle as Black consciousness in action that would resonate throughout the country and across townships and schools in boycotts, strikes and daily discussions. Steve Biko recognised it philosophically, arguing at the time that the “boldness, dedication, sense of purpose and the clarity of analysis of the situation … are definitely a result of Black consciousness ideas among the young generation in Soweto and elsewhere”.

Events are not automatically recognised at the time they take place. Today, what we call the “Durban moment” – a term coined by educationalist Tony Morphet in 1990 – describes not only the massive and seemingly spontaneous strikes across Durban in 1973, but also the political-philosophical discussions between and around Biko and Richard Turner, who was active in organising workers and promoting rank-and-file democracy, education and resistance in the nascent union movement.

It was this notion of recognising a “moment” that was reflected in the subtitle to my book Fanonian Practices in South Africa from Steve Biko to Abahlali baseMjondolo. To include Abahlali in a sequence of politics that began with Biko seemed audacious to some in 2011. My point was that the action, thinking and self-organisation of the shack dwellers in the face of brutal ANC hegemony articulated with Frantz Fanon’s critique of former national liberation leaders as a huckstering caste, and the emergence of new forms of struggle, rooted in humanism, from below in The Wretched of the Earth.

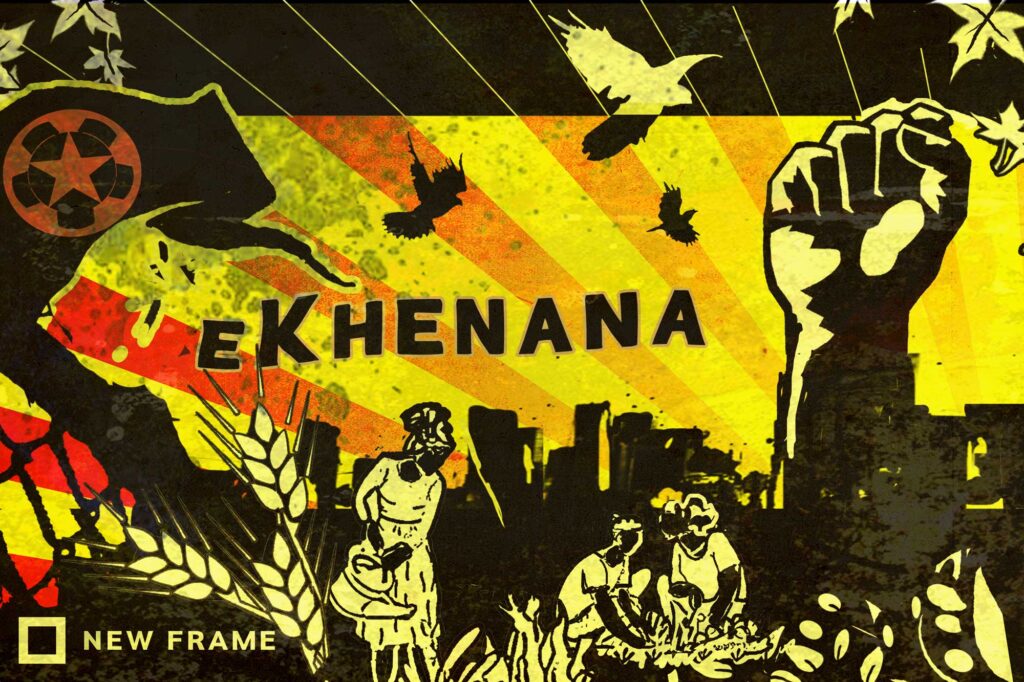

Now, over 16 years after its formation, Abahlali, with a paid-up membership of over 100 000 in five provinces and considerable political weight, is not so easily dismissed as it was by an often contemptuous middle-class Left in those early days. And yet the “commune” at eKhenana in Durban, which has received some mainstream media attention, has not gained recognition as a philosophical-political “event”.

Philosophical events

South Africa is in a crisis in which, as Antonio Gramsci puts it, “the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear”. Subjected to the morbid symptoms on a daily basis – the attempted coup of July 2021 is one expression alongside the daily reality of mass unemployment, xenophobia and violence – we have perhaps focused too much on the normalising morbid symptoms and not enough on intimations of the new that are trying to be born. As Karl Marx wrote in his doctoral thesis in 1841, “necessity is an evil, but there is no necessity to live under the control of necessity. Everywhere the paths to freedom are open.”

To speak of the new is also to be wary of proclamation: we should remember that Marx was wary of an uprising in Paris in late 1870 with the enemy at the gate. And yet once that uprising began, he not only supported it but emphasised the creative elements of imagining a new society as “its own working existence”.

He decided to revise Capital, referencing the idea of freely associated labour as the concrete element that could strip away the fetishistic character of commodities. The Paris Commune was of course world historical, the shattering of state power and its replacement by a really democratic state, as Friedrich Engels put it, “the Kingdom of God, on earth … the sphere in which eternal truth and justice is or should be realised”.

eKhenana is Zulu for Canaan, the promised land of milk and honey where God would deliver the Israelites from Egyptian slavery. By invoking the Paris Commune I am not, of course, putting eKhenana on the same level. The point is to view it through a similar lens, through its own working existence, which has emerged out of the basic need for shelter, food and also the need for community, establishing some important practices that address the question of the decommodification of land, communal organisation, production of food, development of a school for political education, cultural projects such as poetry and theatre, and international solidarity.

Survival is based on the necessities such as shelter, warmth, food and security. We need them for life, but they do not exhaust what it means to be alive. Abahlali’s struggle, and its insistence on thinking in the shack settlements, has always emphasised the importance of ideas. The Frantz Fanon School, a place for community discussions and classes in eKhenana, is a concrete expression of continuing “living learning”, as Abahlali has termed it, just as the theatre of the oppressed is an expression of cultural praxis, aware of how the culture and history of resistance and struggle to, in a phrase often used by Abahlali president S’bu Zikode, “humanise the world” is essential to building the movement.

Revolutionary theatre

Solidarity and collectivity have always highlighted the principle of humanising the world. Under continued repression, solidarity across South Africa and also internationally has importantly come to its defence. Seeds to start the programme of urban farming on occupied land in eKhenana were donated by the MST, the landless workers’ movement in Brazil.

The theatre work there, which has included the collective development and performance of a large-cast play on the assassination of Abahlali leader Thuli Ndlovu in her home in KwaNdengezi in 2014, has inspired similar projects in occupations in other parts of the country. A play titled Theatre of the Oppressed was recently performed in Zikode Village, an occupation in Tembisa named after Abahlali’s president. Written by Musa Nonkwelo, an 18-year-old resident of the occupation, it was purposefully titled and included residents as performers in a play about the story of occupying the land.

Theatre of the Oppressed reaches back to the Black consciousness theatre of the 1970s – represented by groups such as Mhiliti, the People’s Experimental Theatre and Theatre Council of Natal – that was influenced by the work of Paulo Freire and later by Augusto Boal and his concept of theatre as praxis, where the audience takes an active role in analysing and changing reality. As Boal puts it, “perhaps the theatre is not revolutionary in itself; but have no doubt, it is a rehearsal of revolution” because the dramatic action “throws light upon real action” encouraging the spectator to think and act for themselves.

In his preface to the French edition of Capital, Marx applauded the idea that it would come out in instalments, making it “more accessible to the working class”. Similarly, Fanon had hoped that the English translation of The Wretched of the Earth would find new readers across Anglophone Africa. But what could be a more appropriate place to read Marx and Fanon than a school built and run by organised shack dwellers?

Abahlali has organised and supported land occupations for many years. In 2018, the eKhenana Land Occupation was set up in Cato Manor (Mkhumbane in isiZulu). The residents later joined Abahlali and a branch was established in April 2019. Like other occupations, it has been subject to repeated illegal and violent eviction and destruction by the police and private security companies as well as the repeated arrest and imprisonment of its leaders on trumped-up charges. Both the resistance and repression at Mkhumbane have a long history stretching back over 100 years and continuing into the post-1994 period. This is where the movement suffered its first assassination on 26 June 2013 when Nkuleko Gwala was assassinated at a new occupation named Marikana (after the police massacre of striking miners there in 2012).

The decommodification of land

These occupations from below were taking place as the Jacob Zuma ANC was speaking of expropriating land without compensation and pushing for an amendment. Zuma’s politics focused on large areas of farmland. And while the later hearings in South Africa on the amendment of the Constitution to allow for the expropriation of land without compensation was framed in terms of addressing “historic wrongs of land dispossession, ensure fair access to land and empower the majority of South Africans”, landholding in rural areas remained the issue. The pressing problem of access to land in urban areas to build accommodation was almost completely left out. In the government’s estimation the housing backlog in South Africa, if numbers remained the same, would take 30 years to eradicate. And year by year this estimate grows.

While on the face of it there seemed to be agreement, in reality there were two realities and two visions: the ANC’s idea of land as a commodity, tied to the idea of ownership of property “to resolve historic wrongs”, and Abahlali’s idea of the decommodification of land.

In February 2020, Abahlali organised a march of thousands of people through central Durban in support of what it termed the “total decommodification of land”. In March that year, I had a chance to talk about this with Abahlali in Durban. Mqapheli Bonono, who would go on to spend two weeks in prison for his support for the eKhenana commune, said that “we agree on appropriation of land without compensation, [but] we are not following what the ANC and EFF are saying. They understand this to mean take the land from the whites and give it to the Black elite.” Nhlakaniphi Mdiyastha added: “Land must not be sold, must not be put up for rent … it must be owned … communally.”

If land is a commodity it will end up owned by banks, Bonono added, which is why it needs to be decommodified. The dividing line of decommodification was sharply drawn by Abahlali youth member Lindokule Mnguni, a leading figure in the development of the eKhenana commune, who would go on to spend six months in prison after being arrested on trumped-up charges, asked an important question: “How are we going to engage in society without decommodification? Today we don’t even have jobs.” The majority of the residents in eKhenana are unemployed, reflecting a country in which over half the population is under 29 years old and the youth unemployment rate for the youth is over 77.4%. No nation is viable for long under these conditions.

Zikode often repeats Fanon’s statement that “each generation must discover its mission, fulfil it or betray it”. “In the face of all kinds of threat,” Zikode says, “humanity has to rise. No matter what the consequences are. Abahlali has … risen to live [and] … has discovered its mission. We are in a process to fulfil it or betray it.”

Necessity, as Marx puts the basis for freedom, to think past the constraints of the present and imagine the world anew, the work on the commune is part of that reimagining. And it is the Abahlali youth as revolutionary who are taking up this mission. The theatre of the oppressed and the eKhenana commune are its seeds.

eKhenana’s commune is a working existence toward decommodification, decolonising and solidarity. It should be understood as an event with philosophical consequences in a time of deepening social and political crisis.

(Nigel C Gibson’s most recent book is, ‘Fanon: Psychiatry and Politics’, co-authored with Roberto Beneduce, and published by Wits University Press. Courtesy: New Frame, a not-for-profit, social justice media publication based in Johannesburg, South Africa.)