Harsh Mander

If the COVID-19 pandemic lashes India with severity, it will not be just the middle class who will be affected. India’s impoverished millions are likely to overwhelmingly bear the brunt of the suffering which will ensue. The privileged Indian has been comfortable for too long with some of the most unconscionable inequalities in the planet. But with the pandemic, each of these fractures can decimate the survival probabilities and fragile livelihoods of the poor.

The measures adopted by the government to stymie the progress of the virus were first to introduce a ‘work from home’ measure, to urge people to wash their hands frequently, physical distancing, and then an unprecedented 21-day lockdown.

Deepening a social divide

Public health experts are divided about whether this lockdown was absolutely necessary and indeed implementable. It should have been clear that a total lockdown was possible only for the rich and the middle class with assured incomes during the period, homes with spaces for distancing, health insurance and running water supply. But how can we justify the choice of a strategy which throws the dispossessed, who lack all of the above, to both hunger and infection?

When ordering the lockdown, did the government not remember the millions of informal workers and destitute people who would have no work if they stayed home, many of them circular migrants, estimated at 100 million? These include casual daily-wage workers; self-employed people such as rag-pickers, rickshaw pullers and street vendors; and people forced to survive by alms.

Many among them are people whose earnings each day barely suffice to enable them to eat and feed their families. Does the government expect them to voluntarily starve and let their children die to prevent the spread of the infection? This crisis of hunger is even more dire for older people without caregivers, and persons with disability. The government also seems to be in amnesia about hundreds of thousands of children, women and men in every city whose only home is the pavement or the dirt patches under bridges.

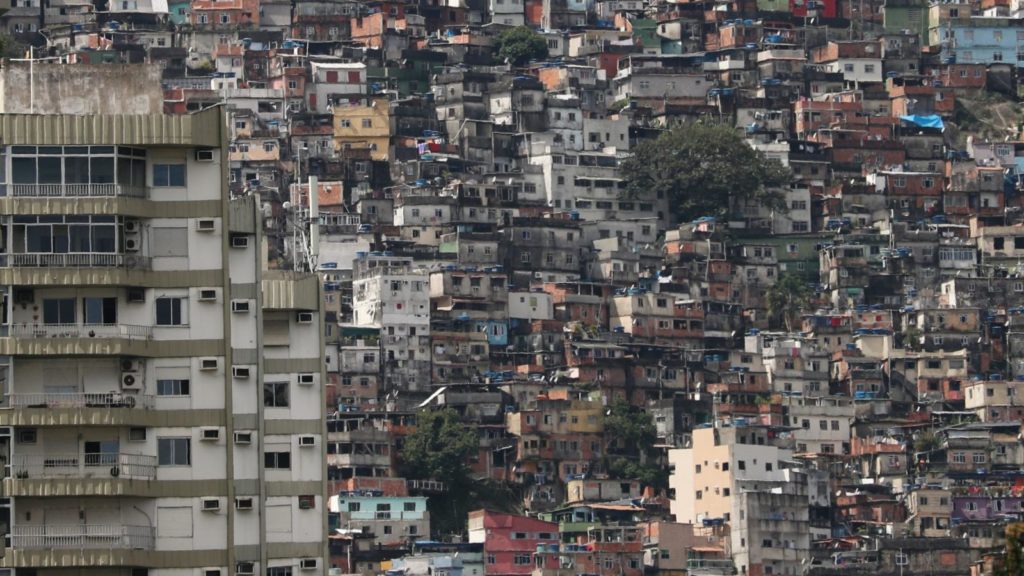

Recorded messages on our phones urge us to wash our hands regularly. We forget, however, that millions live in shanties without water supply, and they buy a pot of water, sometimes for a fifth of their day’s earnings (irregular incomes which are further decimated by the lockdown). Regular cleanliness is a remote luxury beyond their means.

We are also advised ‘social distancing’ (physical distancing) and ‘self-isolation’. How is this feasible for large extended families who crowd into narrow single rooms in slums and working-class tenements? Or for the homeless people who have no option except to sleep in overcrowded unsanitary government shelters, veritable breeding centres for infections? Or for destitute people in beggars’ homes? Indeed, prisoners in overcrowded jails? And I cannot forget those confined to detention centres in Assam, which are jails within jails.

And then consider the capacity of the health system to deal with the pandemic if (or when) it actually submerges India. India’s investments in public health are among the lowest in the world, and most cities lack any kind of public primary health services. A Jan Swasthya Abhiyan estimate is that a district hospital serving a population of two million may have to serve 20,000 patients, but they are bereft of the beds, personnel and resources to do this. Few have a single ventilator. India’s rich and middle-classes have opted out of public health completely, leaving the poor with unconscionably meagre services. The irony is that a pandemic has been brought into India by people who can afford plane tickets, but while they will buy private health services, the virus will devastate the poor who they infect and who have little access to health care.

The Union government has announced a package, including additional 5 kg grain a month for the next three months under the PDS; ₹500 per month for the next three months for women holding Jan-Dhan Yojana accounts; three months’ pension in advance to nearly three crore widows, senior citizens and the differently-abled; and ₹2,000 more for MGNREGA workers. If you and I were told that we have to survive on just two days’ salary and 5 kg grain a month, with no health insurance, how would the future look?

The visuals of thousands of migrants, suddenly left with no food and work, walking to their homes hundreds of miles away, dodging the police, until the States were ordered to seal their borders, showed clearly that the lockdown is ineffective.

What must be done

Most of the official strategies place the responsibility on the citizen, rather than the state, to fight the pandemic. The state did too little in the months it got before the pandemic reached India for expanding greatly its health infrastructure for testing and treatment. This includes planning operations for food and work; security for the poor; for safe transportation of the poor to their homes; and for special protection for the aged, the disabled, children without care and the destitute.

For two months, every household in the informal economy, rural and urban, should be given the equivalent of 25 days’ minimum wages a month until the lockdown continues, and for two months beyond this. Pensions must be doubled and home-delivered in cash. There should be free water tankers supplying water in slum shanties throughout the working days. Governments must double PDS entitlements, which includes protein-rich pulses, and distribute these free at doorsteps. In addition, for homeless children and adults, and single migrants, it is urgent to supply cooked food to all who seek it, and to deliver packed food to the aged and the disabled in their homes using the services of community youth volunteers.

To ensure jails are safer, all prison undertrial prisoners, except those charged with the gravest crimes, should be released. Likewise, all those convicted for petty crimes. All residents of beggars’ homes, women’s rescue centres and detention centres should be freed forthwith.

India must immediately commit 3% of its GDP for public spending on health services, with the focus on free and universal primary and secondary health care. But since the need is immediate, authorities should follow the example of Spain and New Zealand and nationalise private health care. An ordinance should be passed immediately that no patient should be turned away or charged in any private hospital for diagnosis or treatment of symptoms which could be of COVID-19.

While one part of the population enjoys work and nutritional security, health insurance and housing of globally acceptable standards, others survive at the edge of unprotected and uncertain work, abysmal housing without clean water and sanitation, and no assured public health care. Can we resolve to correct this in post-COVID India? Can we at least now make the country more kind, just and equal?

(Harsh Mander is a human rights worker, writer and teacher.)