A drop of your love had blended in

So I drank the entire bitterness of life …

Born in pre-partition Punjab and schooled in Punjabi, Amrita Pritam’s words stand witness to the upheavals of the 20th century wherein she was born. Destined to be a poet, the main concerns of her writing were love, freedom, justice and togetherness.

She brought Punjabi the glory it had never received before, as far as modern writing in the language goes.

Although she wrote in a regional language, Pritam enjoyed an iconic presence that was not just pan-Indian but international. She authored 100 books in different genres—poetry, fiction, essays, biographies, memoirs—as well as a famous autobiography titled The Revenue Stamp (Raseedi Ticket, 1976).

She also edited a Punjabi literary journal called Nagmani for 36 years. Immensely popular, she nurtured two generations of writers, including well-known names like Gurdial Singh, Dalip Kaur Tiwana and Shiv Kumar Batalvi.

The daughter of Nand Sadhu (Kartar Singh Hitkari) and schoolteacher Raj Bibi, a Khatri Sikh couple, Pritam was born with a verse in her heart as her father was a spiritual poet in both the oral and written traditions.

At the age of eight, she helped her father compose poetry. She was only 11 when her mother died. Poetry and daydreams became companions to the lonely child. Tutored by her father in rhyme and metre, she came out with her first book of poetry, Amrit Lehran (Waves of Nectar), written in the spiritual tradition, at age 13.

However, it was at 16—with Thandiyan Kirnan (Cool Rays)—that she received critical acclaim and became the first modern poet of Punjab, eventually being considered a pillar of Punjabi poetry. After that, there was no looking back.

As 2019 heralds her centenary celebrations, we remember the poem that immortalised her, the first dirge to partition by a Punjabi poet writing in any language: Ajj Akhan Waris Shah nu (‘Waris Shah, I Call out to You Today’). She wrote it during a train journey from Delhi to Dehradun in 1948, as a 28-year-old refugee from Lahore:

Today Waris Shah I call out to you

To speak out from the graves

Rise today and open a new page

0f the immortal book of love

A daughter of Punjab once wept

And you wrote many a dirge

A million daughters weep today

and look up at you for solace

Rise o beloved of the aggrieved

just look at your Punjab

Today corpses haunt the woods

Chenab river overflows with blood

Someone has mixed poison

In the Five Rivers of Punjab…

Pritam recounted those times in her autobiography: “The most gruesome accounts of marauding invaders in all mythologies and chronicles put together will not, I believe, compare with the blood curling horrors of this historic year.”

Faiz Ahmad Faiz later read it in jail in Pakistan. When he was released, he found many people had a copy of the poem in their pockets. Writer–journalist Khushwant Singh was the first to translate it into English. He said, “Those few lines she composed made her immortal, in India and Pakistan!”

The other partition work that came out some years later was Pinjar (The Skeleton), which was made into a well-received Hindi film. It relates the story of a Sikh girl who was abducted by a Muslim because of a land feud, as his aunt had earlier been abducted by Sikhs.

Pritam had many firsts to her credit; not only was she the first female Indian writer to receive the National Sahitya Akademi Award for Sunehade (Messages) in 1956, she also received the Padma Shri and Padma Vibhushan awards as well as a nomination to the Rajya Sabha.

She did her language proud by winning the Jnanpith Award in 1982 for Kagaz te Canvas (Paper and Canvas), the first person to win the award for writing in Punjabi. Her many honours also included receiving awards from Bulgaria and France.

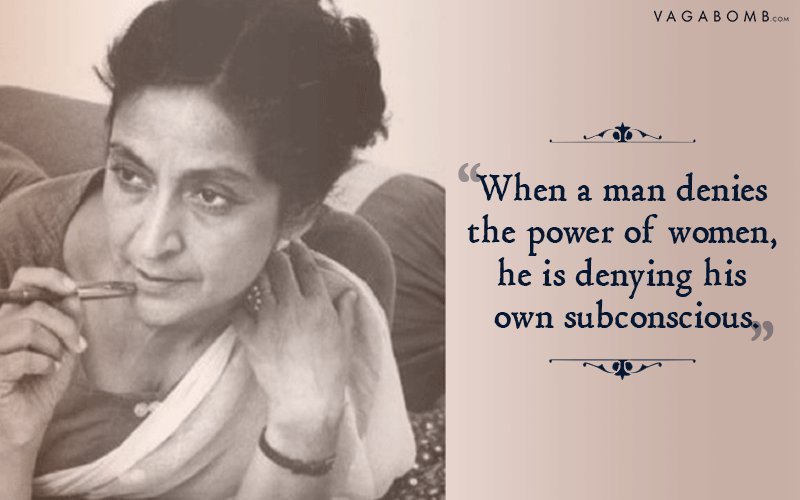

A crusader for gender equality and a woman’s right to live, love and write sans constraint, Pritam was often at the receiving end of unjust criticism. She never bowed to this moral policing.

She walked out of a loveless marriage, had an intense yet platonic romance with the famed Urdu poet Sahir Ludhianvi and, finally, a live-in relationship with artist Inderjit Imroz for nearly half a century.

The personal was indeed the political for her, and she wrote openly about her life, including the smoking of cigarettes—a religious taboo among the Sikh orthodoxy:

There was a pain

I smoked it silently like a cigarette

And a few poems I flicked off

Like ashes from a cigarette …

Through her writing and her life, Pritam paved the way for freedom and choice for young writers, especially girls. As she battled illness towards the end of her life, a precious gift came her way. A few Pakistani writers collected three green chadars (sheets) from the tombs of Sufi poets Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah and Sultan Bahu from across the border and presented her with the line: “You are the Waris (heir) of our Waris!” Such was the love she inspired.

She often said of her poetry: “I have just returned what I learned from the saints, sufis and fakirs of the land of the five rivers!”

This would be followed by a line from one of her poems: Maan suche Ishq da hai, hunar da dava nahi (‘I cherish my chaste dedication and make no claims to the craft’).

Main Tainu Phir Milangi (‘I Will Meet You Yet Again’), dedicated to her partner Imroz, today enjoys an iconic status next only to her ode to Waris Shah:

I will meet you yet again

How and where

I know not

Perhaps I will become a

Figment of your imagination

And maybe spreading myself

In a mysterious line

On your canvas

I will keep gazing at you.

…

When the body perishes

All perishes

But the threads of memory

Are woven of enduring atoms

I will pick these particles

Weave the threads

And I will meet you yet again.

(Nirupama Dutt is a poet, journalist and translator based in Chandigarh. She received the Punjabi Akademi Award for her book of poems Ik Nadi Sanwali Jahi.)