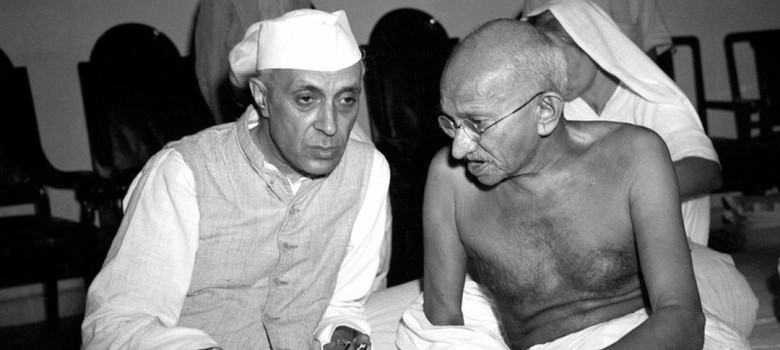

[Jawaharlal Nehru’s extempore broadcast on All India Radio announcing the news of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination on January 30, 1948, “The light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere” is justifiably famous and well-known.

But Nehru made an even greater speech in the Constituent Assembly three days later, on February 2, 1948. In the AIR broadcast, Nehru described Gandhiji’s assassin as a “madman”:

“A madman has put an end to his life, for I can only call him mad who did it, and yet there has been enough of poison spread in this country during the past years and months, and this poison has had an effect on people’s minds. We must face this poison, we must root out this poison, and we must face all the perils that encompass us, and face them not madly or badly, but rather in the way that our beloved teacher taught us to face them.”

This call to respond to Gandhi’s assassination in Gandhian fashion, as Arudra Burra points out, is much more pronounced in the February 2 speech. In one especially striking line, Nehru says:

“Yet he must have suffered, suffered for the failing of this generation whom he had trained, suffered because we went away from the path that he had shown us, and ultimately the hand of a child of his – for he, after all, is as much a child of his as any other Indian – the hand of that child of his struck him down.”

In an age where it is so easy to be “anti-national”, it is a line well worth pondering.

Below is the full text of Nehru’s speech to the Constituent Assembly on February 2, 1948.]

❈ ❈ ❈

It is customary in this House to pay some tribute to the eminent departed, to say some words of praise and condolence. I am not quite sure in my own mind if it is exactly fitting for me or for any others of this House to say much on this occasion for I have a sense of utter shame both as an individual and as head of the government of India that we should have failed to protect the greatest treasure we possessed.

It is our failure in the past many months, to give protection to many an innocent man, woman and child. It may be that that burden and task was too great for us or for any government; nevertheless, it is a failure, and today the fact that this mighty person, whom we honoured and loved beyond measure, has gone because we could not give him adequate protection is shame for all of us. It is shame to me as an Indian that an Indian should have raised his hand against him, it is shame to me as a Hindu that a Hindu should have done this deed and done it to the greatest Indian of the day and the greatest Hindu of the age.

We praise people in well-chosen words and we have some kind of measure for greatness. How shall we praise him and how shall we measure him, because he was not of the common clay that all of us are made of? He came, lived a fairly long span of life, and has passed away. No words of praise of ours in this House are needed, for he has had greater praise in his life than any living man in history and during these two or three days since his death he has had the homage of the world. What can we add to that? How can we praise him? – how can we who have been children of his, and perhaps more intimately children of his than the children of his body, for we have all been in some greater or smaller measure the children of his spirit, unworthy as we were?

A glory has departed

A glory has departed and the sun that warmed and brightened our lives has set and we shiver in the cold and dark. Yet he would not have us feel this way after all the glory that we saw, for all these years that man with divine fire changed us also, and, such as we are, we have been moulded by him during these years and out of that divine fire many of us also took a small spark which strengthened and made us work to some extent on the lines that he fashioned; and so if we praise him our words seem rather small and if we praise him to some extent we praise ourselves.

Great men and eminent men have monuments in bronze and marble set up for them, but this man of divine fire managed in his lifetime to become enmeshed in millions and millions of hearts so that all of us have become somewhat of the stuff that he was made of, though to an infinitely lesser degree. He spread out over India, not in palaces only or in select places or in assemblies, but in very hamlet and hut of the lowly and of those who suffer. He lives in the hearts of millions and he will live for immemorial ages.

What then can we say about him except to feel humble on this occasion? To praise him we are not worthy, to praise him whom we could not follow adequately or sufficiently. It is almost doing him an injustice just to pass him by with words when he demanded work and labour and sacrifice from us in large measure. He made this country during the last thirty years or more attain to heights of sacrifice which in that particular domain have never been equalled elsewhere. He succeeded in that, yet ultimately things happened which, no doubt, made him suffer tremendously, though his tender face never lost its smile and he never spoke a harsh word to anyone. Yet he must have suffered, suffered for the failing of this generation whom he had trained, suffered because we went away from the path that he had shown us, and ultimately the hand of a child of his – for he, after all, is as much a child of his as any other Indian – the hand of that child of his struck him down.

The living flame

Long ages afterward history will judge of this period that we have passed through. It will judge of the successes and failures. We are too near to be proper judges of and understand what has happened and what has not happened. All we know is that there was glory and that it is no more. All we know is that for the moment there is darkness: not so dark, certainly, because when we look into our hearts we still find the living flame which he lighted there, and if those living flames exist there will not be darkness in this land and we shall be able with out effort, praying with him and following his path, to illumine this land again, small as we are, but still with the fire that he instilled into us.

He was perhaps the greatest symbol of the India of the past, and, may I say, of the India of the future, that we could have. We stand in this perilous age of the present between that past and the future to be, and we face all manner of perils, and the greatest peril is sometimes a lack of faith that comes to us, the sinking of the heart and of the spirit that comes to us when we see ideals go overboard, when we see the great things that we talked about somehow pass into empty words and life taking a different course. Yet I do believe that perhaps this period will pass soon enough.

Great as this man of God was in his life, he has been greater in his death, and I have no shadow of a doubt that by his death he has served the great cause as he served it throughout his life. We mourn him, we shall always mourn him, because we are human and cannot forget our valued master; but I know that he would not like us to mourn him. No tears came to his eyes when his dearest and closest went away, only the firm resolve to persevere, to serve the great cause that he had chosen. So he would chide us if we merely mourn. That is a poor way of doing homage to him.

The only way is to express our determination, to pledge ourselves anew, to conduct ourselves so and to dedicate ourselves to the great task which he undertook and which he accomplished to such a large extent. So we have to work, we have to labour, we have to sacrifice, and thus prove to some extent at least worthy followers of his…

Root out the evil

This happening, this tragedy, is not merely the isolated act of a madman. It comes out of a certain atmosphere of violence and hatred that has prevailed in this country for many months and years, and more especially in the past few months. That atmosphere envelops us and surrounds us, and if we are to serve the cause he put before us we have to face this atmosphere, to combat it, struggle against it, and root out the evil of hatred and violence.

So far as this government is concerned I trust they will spare no means, spare no effort to tackle it, because if we do not do that, if we in our weakness or for any other reason that we may consider adequate do not take effective means to stop this violence, to stop this spreading of hatred by word of mouth or writing or act, then, indeed, we are not worthy of being in this government, we are not certainly worthy of being his followers, and we are not worthy of even saying words of praise for this great soul who has departed.

So that on this occasion or any other when we think of this master who has gone, let us always think of him in terms of work and labour and sacrifice, in terms of fighting evil wherever we see it, in terms of holding to the truth, as he put it before us, and if we do so, however unworthy we may be, we shall at least have done our duty and paid the proper homage to his spirit.

He has gone, and all over India there is a feeling of having been left desolate and forlorn. All of us sense that feeling and I do not know when we shall be able to get rid of it. And yet, together with that feeling, there is also a feeling of proud thanksgiving that it has been given to us of this generation to be associated with this mighty person.

In the ages to come, centuries and maybe millenniums after us, people will think of this generation when this man of God trod the earth and will think of us who, however small, could also follow his path and probably tread on that holy ground where his feet had been. Let us be worthy of him, let us always be so.

(Courtesy: Scroll.in.)