Ayesha Khan

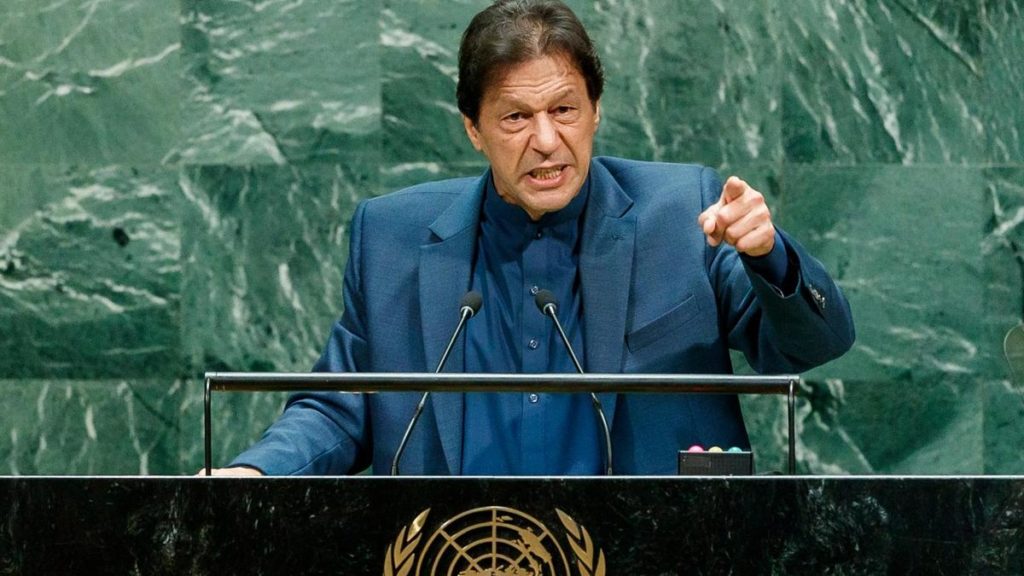

When Imran Khan became Prime Minister of Pakistan he vowed to eradicate inequality. As an opposition leader he campaigned on the slogan, Do nahin, aik Pakistan (Not two but one Pakistan) and his party, Tehreek Insaaf, which translates as “The Party of Justice,” promised justice for all. Yet the very idea of justice has been turned on its head under his watch.

Two years ago, Naqueebullah Mehsud, an ethnic Pashtun and an aspiring model, was wrongly profiled as a terrorist and killed in a staged police encounter in Karachi. The man allegedly responsible is Rao Anwar, a senior superintendent of police, who is accused of having conducted more than 400 such extrajudicial “encounter killings”.

In the aftermath of Naquibullah’s high profile murder however, Pashtuns from his tribe began a protest movement demanding justice that grew to include the families of several other victims who had suffered ethnic profiling, enforced disappearances and harassment at the hands of security forces. The movement became known as the Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) and galvanised under the leadership of the young and charismatic Manzoor Pashteen.

Prior to the July 2018 election, Imran Khan appeared sympathetic to PTM and even attended some of their rallies to show support. Since he has taken office however the PTM has seen a brutal crackdown. Although the movement is entirely non-violent and their rallies are organised as peaceful protests, the questions that they ask of the military and security forces are embarrassing for the deep state. As a result, they are denied any space in the media. In fact, one of their supporters, Sana Ejaz, lost her job with the state broadcaster only because she was sympathetic to the movement.

They demand basic rights enshrined within the framework of the Pakistani Constitution but are routinely painted as traitors or foreign agents. In May, two of their leaders who were elected as members of Parliament from North and South Waziristan in the 2018 election were crossing a security checkpoint along with their supporters in their native Waziristan when soldiers fired at them, killing three and wounding several others.

The military claims the protesters assaulted the post but video footage released on social media showed shots being fired from behind at unarmed protesters. In the aftermath of this Kharqamar incident, Ali Wazir and Mohsin Dawar, both of whom are members of Parliament and were leading the PTM protest, were arrested and sent to prison for four months.

Tragically, Rao Anwar, the man accused of killing hundreds, has managed to stay out of prison. Even an art exhibit honouring his victims and depicting police brutality by an artist in Karachi was ordered to be shut down in October because the authorities said that it paints Pakistan in a poor light.

But PTM remains a thorn in the deep state’s side. While leaders of the mainstream political parties, Asif Zardari of the Pakistan People’s Party and Nawaz Sharif of the Pakistan Muslim League, whom Imran has consistently accused of mega-corruption have been let out of jail as they appear to have compromised with the military establishment, the PTM refuses to compromise on its principles.

While previously they accused the military of rigging the 2018 election, resulting in Imran Khan’s “selection, not an election” as PPP’s Bilawal Bhutto famously said, recently both PPP and PML-N have assented to a controversial three year extension for the army chief, Qamar Javed Bajwa. Upsetting supporters who want to see civilian supremacy and democracy strengthened in Pakistan they nevertheless signalled to the powerful military establishment that if Imran Khan fails to deliver (the economy is in dire straits) either one of these parties will be willing to take his place in the hybrid democracy.

The PTM members of Parliament however voted against the extension. And although they currently only have two seats in Parliament and are therefore not able to influence voting patterns, they do continue to attract huge crowds in their rallies. A recent rally in Bannu attracted such massive crowds that it resulted in the arrest of Manzoor Pashteen. And while PTM cannot be discussed in the local media, in a recent interview to the BBC, Interior Minister, Ijaz Shah, claimed Pashteen was arrested because he did not protest in “the right way”.

Yet his peaceful and principled ways find traction among civil society activists and many came out to protest his arrest in Islamabad. Among them were students, college professors, women’s rights and climate change activists. Some had no political affiliation and were not Pashtun but came out in solidarity. They too were arrested and taken to jail on sedition charges, and although most were subsequently released on bail, those who exercise the right to free speech or lawful assembly in Pakistan are increasingly vulnerable to state brutality.

Over the last year and a half, opposition politicians have been jailed on fabricated charges, judges have been harassed for questioning the military’s role in politics, lawyers have been abducted for representing missing people, journalists have been muted on air and several have lost their jobs and now students and their teachers have been charged with sedition. Although Imran Khan promised a better Pakistan, not since Zia ul Haq’s military dictatorship in the eighties has Pakistan seen such a repressive attack on basic freedoms.

(Ayesha Khan is a lawyer and author of “Rodeo Drive to Raja Bazaar”.)