Katiuska Blanco

[August 9, International Day of American Crimes Against Humanity.]

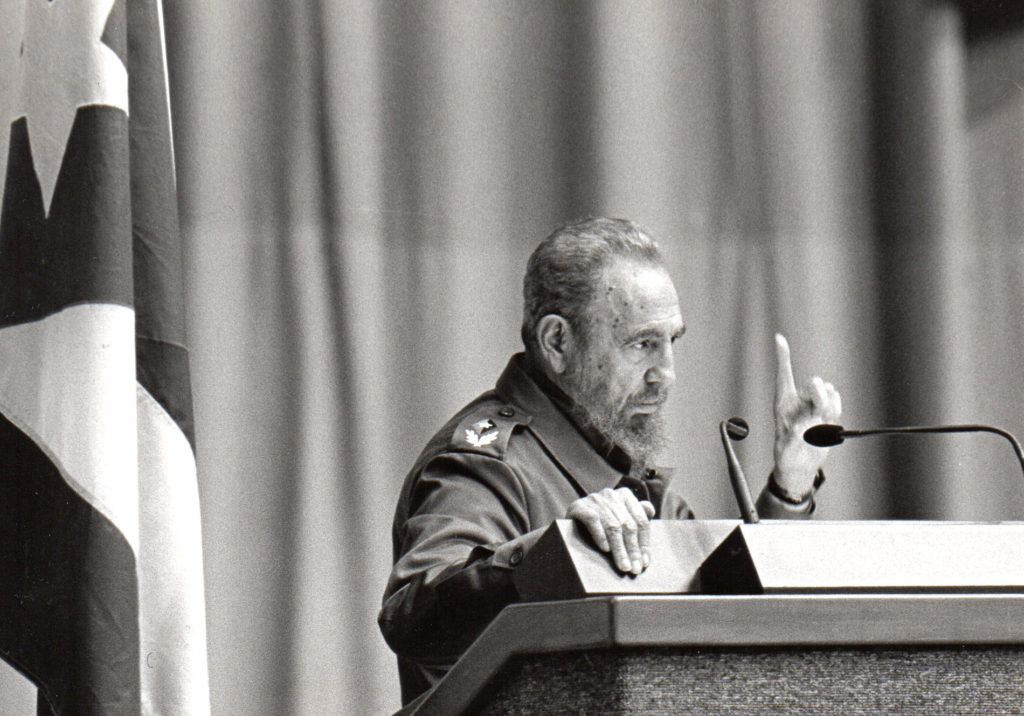

The launch of the atomic bomb on the unarmed cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on August 6 and 9, 1945, dramatically and unforgettably moved Fidel. He recognized the accounts of the explosion and its terrible consequences as overwhelming. Only a few weeks before, he had finished his high school studies at the Belen School and, on his return to the intimate space of the big house in Biran, he was getting ready to study law at the University of Havana in September of that year. At the time the news of the bombing of Hiroshima was announced, Fidel was visiting Santiago de Cuba. No one then had the slightest idea of the existence of such a weapon. Three days later they bombed Nagasaki. He experienced a feeling of repulsion and a total rejection of that criminal act, an opinion that remained unchanged throughout his life.

Since 1936, when he was ten years old in Biran, he had begun to worry about what was happening in the world, when he read the news of the Spanish Civil War aloud to the cook Manuel Garcia, which, with greater or lesser fortune for the Republican side, was reported in the newspapers that arrived from the capital. From the middle of the previous year – 1935 – and during the months that it lasted, he followed the war in Abyssinia with great interest. Thus, he had, for the first time, the notion that the world was an unsettled and unjust place, where great battles were still being fought. Heroes and anti-heroes were not something of the past or remote antiquity. While he was studying in schools he felt a tremendous fascination for the outstanding personalities of history, such as Alexander the Great, Hannibal or Napoleon, as well as a deep respect and admiration for those who were not conquerors, but liberators of the people: Miranda, Simón Bolívar, Sucre, San Martín, and an almost immediate admiration and pride for those who were closest and most dear to the inhabitants of the Cuban archipelago: the Apostle José Martí, Generalissimo Máximo Gómez and the Bronze Titan Antonio Maceo.

In 1939 the Second World War erupted. At the age of 13 or 14, he kept up with the developments on the war front. The events of the time left a deep mark on him. He could not yet foresee that in order to defend noble causes, he would have to wage a guerrilla struggle in the mountains and then in the international arena as a gladiator of peace, solidarity and justice in defense of peoples, the humble, all of humanity, against imperial hegemonic domination and globalized capitalism. On that path, inexorably, would be the memory of the devastation and suffering caused by the inhumane and criminal American atomic bombing of the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a tragedy that brought before their eyes the devastating power of another kind of war.

Fidel was convinced of Martí’s principle: “Trenches of ideas are worth more than trenches of stone”, and he always believed that for war of a popular nature, empires had no effective formula, that for conventional war, a war against a people, not all the military and technological force in the world was sufficient. He gave a historical example, that of Napoleon, who, in his own words, “was a victorious general in all of Europe, he invaded Spain and the Spanish people defeated him. All Napoleon’s strategic capacity, all his manoeuvres, fighting against peasants, workers of the people, were useless; they defeated him with another kind of resistance. Perhaps Napoleon, against a Spanish army of 100,000 men, would defeat them, just as he did at Austerlitz and in so many other places. He himself was defeated at Waterloo, a battle he had won; but an enemy force he thought was distant suddenly appeared and defeated him. That kind of battle can be won or lost, but in war with the people, it is difficult.”

But what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki presented another, radically different situation, beyond anything he had read in the newspapers or in Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace, a novel that addresses a crucial crossroads where the author reflects on what a conflict means in terms of loss and pain. From the criminal atomic bombing of Japan by the United States, Fidel had the clear conviction that in our time, there was another type of war, a war of apocalyptic dimensions, devastating even for the existence of the human species on the planet: nuclear war, which Cuba was on the verge of during the October Crisis in 1962. A threat that persisted throughout time and remained latent in his thoughts as a concern and a reason for the struggle for peace for all peoples.

In Fidel’s opinion, the problems posed by nuclear war are unsolvable and that is why he always maintained that the best thing would be for all nuclear weapons to be destroyed. He tirelessly advocated total disarmament so that the Earth would not be forced to live with the perennial danger of a war of such magnitude, a true cataclysm. He warned that even by mistake, such a tragedy could be unleashed, because unfortunately, the colossal energies that scientists had been capable of placing in the hands of man had served, among other things, to create a self-destructive and cruel instrument like the nuclear weapon.

In March 2003, after an intense journey that took him to China, Vietnam and Malaysia, where he attended the Thirteenth Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement, during a transit visit to Japan, the historic leader of the Cuban Revolution arrived in the city of Hiroshima. He said that, unfortunately, what happened did not serve as a lesson to the world. He recalled that after the terrible events there, the world was heading for an incredible arms race. He visited the Peace Memorial, where silence is overwhelming and every year the victims of the nuclear holocaust are remembered. In the book of homage, Fidel wrote: “May such barbarism never occur again”. It hurts in the deepest sense to think that such an act took place to intimidate the Soviet Union and all the peoples of the world, and to ensure geopolitical superiority then, and not, as some historians tell us, to win the war against the Japanese Empire, allied with fascist Germany and Italy.

On September 21, 2010, Fidel met with more than 600 passengers of the Peace Cruise in Havana, almost all of them Japanese nationals, among whom was a survivor of the mass murder, Junko Watanabe, a member of the Hibakusha movement. The Commander-in-Chief of the Cuban Revolution valued the meeting with those who stood out for their accumulated experience in the struggle for peace as very special and important, based on the testimonies and heartbreaking experiences of such a brutal and unprecedented event, where nuclear weapons were used on two peaceful cities. He then pointed out that the Cruise project was an example of the things that help to raise awareness, because the exhibition of everything that happened there and the human damage it caused, despite the time that had passed, moved international public opinion once again. “I don’t think,” he said, “that anything has happened that is more expressive of what war is”.

On February 14, 2016, Fidel stated in a Reflection signed eighteen minutes after ten o’clock that night:

“Peace has been the golden dream of humanity and the yearning of the peoples in every moment of history. …] To fight for peace is the most sacred duty of all human beings, whatever their religion or country of birth, the colour of their skin, in their adulthood or youth”.

On the eve of 13 August 2016, when he would turn 90 years old, he published a Reflection entitled “The Birthday“, and near the end of it he stated:

“I believe that the speech by the President of the United States [Barack Obama] when he visited Japan lacked stature, and it lacked an apology for the killing of hundreds of thousands of people in Hiroshima, in spite of the fact that they knew the effects of the bomb. The attack on Nagasaki was equally criminal, a city that the masters of life and death chose at random. It is for that reason that we must hammer on about the necessity of preserving peace, and that no power has the right to kill millions of human beings”.

Denunciation, eternal battle, vehement militancy for solidarity and justice that Fidel left to us to serve as a compass for these days.

(Katiuska Blanco Castiñeira is a Cuban journalist and essayist.)