✫✫✫

Nuclear War or Invasion: The False Dichotomy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Brett Wilkins

Seventy-five years ago, the United States waged the only nuclear war in history. Among the truths held self-evident by millions of Americans is the notion that the atomic destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki saved lives, both American and Japanese. The choice, Americans are told starting as school children and throughout their lives by largely uncritical media, was between nuclear war and an even bloodier protracted invasion of Japan, whose fanatical people would have fought to the death defending their homeland and their divine emperor.

As with so many other dark chapters in US history, the official narrative of the decision to unleash the most destructive weapon humanity has ever known upon an utterly defeated people is deeply flawed.

‘Anxious to Terminate’

The Japanese had in fact been trying to find a way to surrender with honor for months before the atomic bombs were dropped, and US leaders knew it. Japan could no longer defend itself from the ruthless, relentless US onslaught; years of ferocious firebombing had reduced most Japanese cities, including the capital Tokyo, to ruins. General Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay, commander of strategic bombing, even complained that there was nothing left to bomb there but “garbage can targets.”

After years of war and privation, Japan’s people had had enough, and so had many of its leaders. The Allies, through a secret cryptanalysis project codenamed Magic, had intercepted and decoded secret transmissions from Shigenori Togo, the Japanese foreign minister, to Naotaki Sato, the ambassador in Moscow, stating a desire to end the war.

“His Majesty is extremely anxious to terminate the war as soon as possible,” Sato cabled on July 12. However, saving face was imperative to the Japanese, which meant retaining their sacred emperor. Unconditional surrender was, for the time being, out of the question.

In a secret memo dated June 28, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph A. Bard wrote that “the Japanese government may be searching for some opportunity which they could use as a medium of surrender.” In a 1960 interview, Bard reiterated that “the Japanese were ready for peace and had already approached the Russians” about capitulating.

On July 26, the leaders of the US, Britain and China issued the Potsdam Declaration, demanding unconditional Japanese surrender and vowing “prompt and utter destruction” – the US had successfully tested the first atomic bomb in New Mexico 10 days earlier – if Japan refused. The declaration was originally written so that Emperor Hirohito would not be removed from the Chrysanthemum Throne, with Japan to be ruled as a constitutional monarchy after the war.

However, Secretary of State James Byrnes removed that language from the final declaration. It would be unconditional surrender or total annihilation.

President Harry S. Truman, who only learned about the Manhattan Project after being sworn in following Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death on April 12, approved a plan to drop two atomic bombs on Japan. Planners sought undamaged cities where military facilities were located near civilians, and the decision was made to detonate the bombs hundreds of meters in the air for maximum destructive effect.

Tokyo, which in early March suffered firebombing that killed more people than either of the atomic bombs, was off the table as a target. Kyoto was spared due to its cultural significance. Kyoto’s good fortune would mean the Nagasaki’s destruction. Hiroshima, Japan’s largest untouched target, would die first.

Widespread Opposition

Seven of the eight five-star US generals and admirals in 1945 opposed using the atomic bomb against Japan. One of them, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, later said that “the Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing.”

“Japan was already defeated and dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary,” President Eisenhower wrote in 1954. “I thought our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was no longer mandatory to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of face.”

Despite so much high-level misgiving, the US did “hit them with that awful thing.” The idea of giving Japanese officials a live demonstration of an atomic bomb on a remote island, proposed by Strategic Bombing Survey Vice Chairman Paul Nitze and supported by Navy Secretary James Forrestal, was rejected. The US was already destroying multiple Japanese cities every week; it was believed that such a demonstration would likely not have moved the Japanese any more than the ongoing destruction of their actual cities.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1945, Japanese officials increasingly sought an honorable end to the war. Although they had no way of knowing that the US was planning to wage nuclear war against them, they knew that the defeat of Nazi Germany meant that a Soviet invasion, first of Manchuria and Korea and then of Japan itself, was now imminent.

“The Japanese could not fight a two-front war, and were more anti-communist than the Americans were,” Martin Sherwin, an historian awarded the Pulitzer Prize for co-authoring a biography of Manhattan Project leader Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, said a recent webinar sponsored by over two dozen international peace organizations. “The idea of a Soviet occupation of Japan was their worst nightmare.”

Historian and professor Peter Kuznick, who with Oliver Stone co-authored the bestselling The Untold History of the United States, also spoke at the webinar, adding that “the Joint Chiefs of Staff repeatedly reported that if the USSR should enter the war then Japan would realize that defeat is inevitable.” Kuznick also noted that General George Marshall, the only five-star US officer to approve of using the atomic bomb, said that a Soviet invasion would likely lead to Japan’s swift surrender.

Truman knew this too. On the opening day of the Potsdam Conference, he had lunch with Joseph Stalin. Afterwards he wrote in his diary that the USSR “will be in the Jap war by August 15. Fini Japs when that occurs.”

Regardless, Truman pressed ahead with the plan to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki while attempting to convince himself that there was some humanity in the act. “I have told Secretary of War Stimson to use [the A-bomb] so that military objectives… are the target, not women and children,” the president wrote in his diary on July 25.

“Even if the Japs are savages, ruthless, merciless and fanatic, we as the leader of the world for the common welfare cannot drop that terrible bomb on the old capital [Kyoto] or the new [Tokyo],” he added. “The target will be a purely military one.”

The First Nuclear War

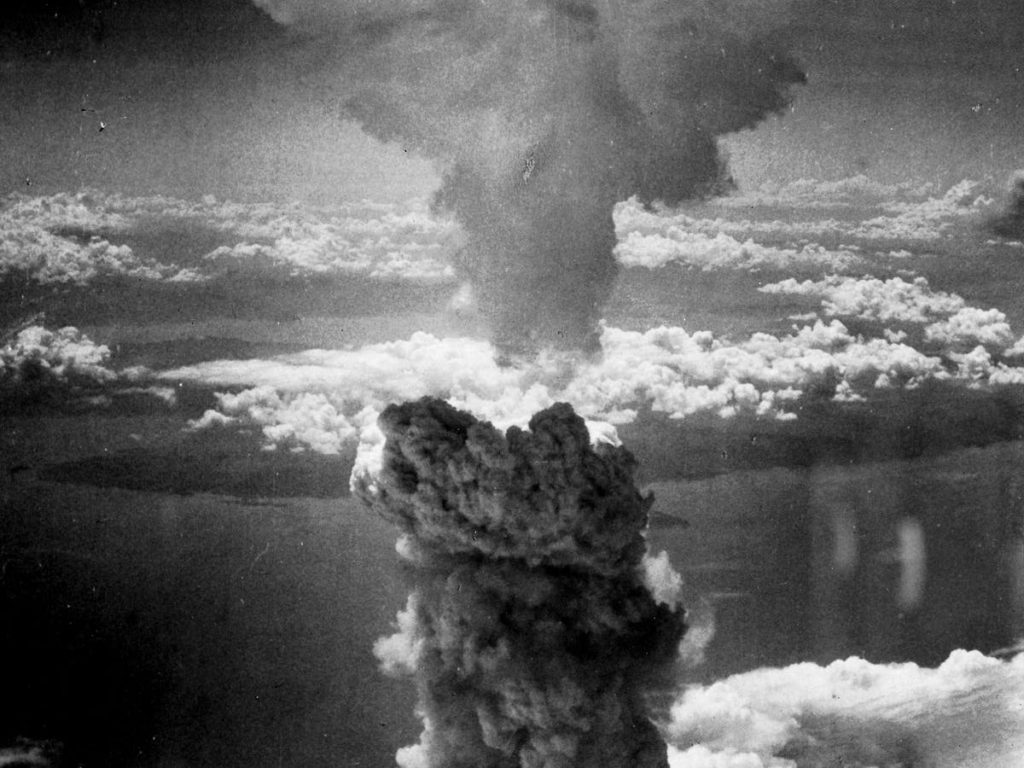

At 8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress dropped “Little Boy,” the first nuclear weapon ever used in war. It exploded above Hiroshima with the force of 16 kilotons of TNT, destroying everything and everyone within about a 1-mile (1.62 km) radius. The heat, blast wave and ensuing inferno killed as many as 90,000 people. Tens of thousands more were injured, many of them mortally. Tens of thousands more people perished from radiation over the following weeks, months and years.

Three days later, Nagasaki suffered a similar fate as “Fat Man,” the second and so far the last nuclear weapon used in war, obliterated Nagasaki in a 20-kiloton air burst. As many as 75,000 people died that day, with a similar number of people wounded and tens of thousands more dying later from radiation.

Despite Truman’s attempt at self-delusion, most of the people living in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 were women, children and old people, as most of the men were away fighting the war, or dead from it.

The same morning that Nagasaki was destroyed, Prime Minister Kintaro Suzuki addressed the Japanese cabinet, declaring that “under the present circumstances I have concluded that our only alternative is to accept the Potsdam Proclamation and terminate the war.”

Why Japan Really Surrendered

Suzuki did not learn about Nagasaki until the afternoon of August 9. But he did know that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan the previous day. This, Japanese officials and historians on both sides of the Pacific agree, precipitated Japan’s surrender more than the A-bombs, although it also slammed the door shut on attempts to negotiate a surrender via Moscow.

“The destruction of another city was just the destruction of another city,” said Sherwin. “It was the entry of the Soviets into the war that really threw the Japanese into a complete panic.” They knew that if they didn’t surrender soon to the US, they would lose not only their overseas empire, but also Hokkaido.

An exhibit at the National Museum of the US Navy in Washington, DC states that “the vast destruction wreaked by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the loss of 135,000 people made little impact on the Japanese military. However, the Soviet invasion of Manchuria changed their minds.”

“The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all,” General LeMay stated flatly in September 1945.

“The use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan,” agreed Admiral William Leahy, Truman’s chief of staff. “The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender because of the effective sea blockade and the successful bombing with conventional weapons.”

It is probably too much to say the atomic bombings had nothing to do with ending the war. Hirohito, after all, spoke of “a new and most cruel bomb” that could “lead to the total extinction of human civilization,” in his surrender broadcast. It is also important to note that the decision to capitulate was not unanimous; in fact, a cabal of hard-line military officers attempted to stage a coup the day before the emperor’s announcement.

Target: Moscow

Not only were Hiroshima and Nagasaki the last battles of World War II, they were also the first battles of the Cold War. American leaders knew very well that the Soviet Union would feature prominently in the postwar world order. The US wanted to maximize its own position as the dominant world power, and what better way to do this than to show the Russians that the United States had the cold resolve necessary to unilaterally wage nuclear war, even when it enjoyed an atomic monopoly and dropping the bomb wasn’t even necessary?

Stimson acknowledged that some US officials saw nuclear weapons as “a diplomatic weapon,” and that “some of the men in charge of foreign policy were eager to carry the bomb as their ace-in-the-hole” and wanted “to browbeat the Russians with the bomb held rather ostentatiously on our hip.”

“I’ll certainly have a hammer on those boys,” Truman reportedly said, referring to the A-bomb and Soviet leaders.

According to Manhattan Project scientist Leo Szilard, Secretary Byrnes believed that “Russia might be more manageable if impressed by American military might, and that a demonstration of the bomb might impress Russia.”

But instead of “managing” Russia, some US officials admitted that waging nuclear war actually empowered it, encouraging Moscow to rush to develop its own nuclear arsenal, which it did in 1949.

‘A Nice, Round Figure’

As for the common claim that a US invasion of Japan would have cost a million lives, Kai Bird, who shared the Pulitzer Prize with Sherwin for their Oppenheimer biography, said it is simply not true.

“This figure was never given to Truman or bandied about by Stimson,” Bird told the webinar audience. “I asked [Stimson protégé] McGeorge Bundy about it, and he sheepishly admitted that he chose 1 million because it was a nice, round figure. He pulled it out of thin air.”

There is no doubt that an invasion of Japan would have been horrific for all involved, as demonstrated by the bloody battle for Okinawa, in which over 12,000 US invaders and six times that number of Japanese defenders died, along with as many as half of the island’s 300,000 civilians, many of whom committed mass suicide rather than fall under enemy occupation. However, the probability of Japan remaining in the war by the time the US was ready to invade was extremely low, especially given the Soviet Union’s declaration of war.

Plus, the claim that the United States cared anything about the lives of Japanese people, who were portrayed in wartime propaganda as sub-human barbarians, beggars belief. US bombs and bullets had killed over a million Japanese people by 1945, and back in the United States, Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals – who had been banned from even immigrating to the US since the 1920s – were still languishing in a network of concentration camps.

Being mere “dirty Japs” made it easier for the Americans to try out their ultimate weapon, in which so much time and treasure had been invested. The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki would make perfect laboratories in which to test the atomic bomb, as some US officials later acknowledged.

“When we didn’t need to do it, and we knew we didn’t need to do it, and they knew that we didn’t need to do it, we used [the Japanese] as an experiment for two atomic bombs,” said General Carter Clarke, the intelligence officer in charge of intercepted Japanese cables.

Tough Luck

Many of the very men who invented the A-bomb also had grave misgivings, even before it was used. These Manhattan Project scientists wrote what came to be known as the Franck Report in May 1945. It recommended a demonstration of the bomb to the Japanese and questioned whether using it would really bring Japan to its knees when massive conventional bombing had failed to do so.

“If no international agreement is concluded immediately after the first detonation, this will mean a flying start of an unlimited armaments race,” the report prophetically stated.

One notable participant in the events of August 6, 1945 had no regrets. Paul Tibbets flew the B-29 bomber, named Enola Gay after his mother, that let loose “Little Boy” over Hiroshima on that fateful morning. Asked at age 87 about doing it again, Tibbets, who died in 2007, said he “wouldn’t hesitate if I had the choice.”

“I’d wipe ’em out,” he said. “You’re gonna kill innocent people at the same time, but we’ve never fought a damn war anywhere in the world where they didn’t kill innocent people. If the newspapers would just cut out the shit: ‘You’ve killed so many civilians.’ That’s their tough luck for being there.”

A False Choice

Seventy-five years later, a slim majority of Americans still believe the nuclear war against Japan was justified. Millions of Americans believe the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were acts of “necessary evil,” while ignoring alternatives to the standard narrative that the only choice was between nuclear war and invading Japan.

What if the United States had clarified its unconditional surrender stance to assure that Hirohito would not be hanged? Or announced that he would be allowed to remain in a position of ceremonial leadership? After all, General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Allied Commander, would ultimately allow Hirohito to remain emperor, even if only as a figurehead.

“It is possible,” wrote Stimson in his memoir, “that an earlier exposition of American willingness to retain the emperor could have produced an earlier ending to the war.”

It is also possible, adds Sherwin, “that unconditional surrender would have been qualified earlier” if the atomic bomb wasn’t being developed and tested for use.

“Most historians know this, but most Americans regurgitate the official narrative,” Bird told the webinar audience.

The official US narrative blames the Soviet Union for starting the Cold War and the nuclear arms race, which on numerous occasions over the following decades brought the world within reach, and once to the brink, of thermonuclear annihilation. But it was the United States that fired the first fiery salvo, forcing the Soviets to scramble to develop their own deterrent and launching an arms race in which there are now thousands of nuclear warheads in the arsenals of a record number of countries, with the risk of nuclear armageddon as real as it has ever been.

Americans must admit that the nuclear war against Japan was one of the greatest atrocities in human history. For the first time ever, we humans now have the power to bring about our own extinction. There is absolutely nothing “necessary” about this evil.

“If we’d lost the war, we’d all have been tried as war criminals,” General LeMay remarked, according to Robert McNamara, who brought maximum efficiency to B-29 bombing during the war and maximum death and destruction to Vietnam as secretary of defense during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

He added: “What makes it immoral if you lose but not immoral if you win?”

(Brett Wilkins is editor-at-large for US news at Digital Journal. Based in San Francisco, his work covers issues of social justice, human rights and war and peace.)

✫✫✫

75 Years On: Reflections and Preflections on Hiroshima

Robert Freeman

This week is the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is worthwhile re-examining what happened and what it can tell us about our world today.

As is so often the case in complex—to say nothing of controversial—events, we have to scope out a little to see the context of what was going on at the time. Doing so gives us a perspective rarely seen before.

Though it wasn’t yet quit, Japan’s war in the Pacific was lost in October, 1944, at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. There, the Japanese Imperial fleet was destroyed. This was an ocean-based war and there was nothing left to defend the home islands from attack.

So, beginning in March of 1945, the U.S. began uncontested saturation bombing of Japan. Long range bombing runs over Tokyo, Osaka, Kobe, Nagoya, and Yokohama included scores, and later, hundreds of airplanes at a time.

Regarding one such run, on March 10, 1945, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey wrote, “probably more persons lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a six-hour period than at any time in the history of man.”

On another run, in April 1945, 200 U.S. planes dropped 1,600 tons of incendiary explosives on Tokyo, obliterating 36 square miles of the inner city. The updrafts from the heat tossed the airplanes around like toys. The bombings were one of the most disproportional inflictions of sustained violence against a defenseless foe in the history of warfare. Still, the Japanese had not surrendered.

But by May, the Emperor recognized the inevitable. The carnage was apocalyptic and escalating. Defeat was imminent and unavoidable. He instructed his cabinet to approach the Soviet Union and request its help in negotiating a surrender with the U.S. The U.S. knew this because even before Pearl Harbor it had broken the Japanese codes.

But the Soviet Union was conflicted. At Yalta, in February 1945, Franklin Roosevelt had secured the promise from Stalin that ninety days after the end of the War in Europe, the Soviet Union would enter the War in the Pacific and help the U.S. secure the defeat of Japan. So, Japan’s entreaties to the Soviet Union went nowhere.

The War in Europe ended on May 8th, 1945. May 8th plus 90 days is August 8th. Remember, Hiroshima was August 6th. The details of the timing are critical.

The first atomic bomb was exploded at Alamogordo, New Mexico on July 16. It held the possibility of inflicting such massive, instantaneous damage that Japan would be forced to surrender immediately, and unconditionally. This was deemed imperative by U.S. authorities in order to keep the Soviets out of east Asia.

If the Soviet Union entered east Asia, it would secure land there similar to what it had taken in eastern Europe while defeating Hitler. There, it had occupied more than 150,000 square miles of what was Poland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia, and other countries.

Also, before the War began in the Pacific, China had been in the midst of a civil war, between nationalists, supported by the U.S., and communists, supported by the Soviet Union. That war had been interrupted by the World War, and would inevitably resume once the greater war was over.

The communists, led by Mao Zedong, had the mass of the people behind them, and had been winning the civil war before it was suspended. The Soviets would undoubtedly throw their weight behind the communists, tipping the most populous nation on earth into their camp. This was crucial.

It would be the U.S.’s greatest nightmare to have fought the War to defeat one foe—fascism—only to lose it at the very end to another, perhaps even more menacing foe—communism. There was also the important matter of the fate of the developing world.

For the prior four centuries, European states had been colonial powers, amassing empires that spanned the globe. The phrase, “The sun never sets on the British Empire” was emblematic, and applied, albeit in lesser force, to other European nations as well: France; Spain; Portugal; Germany; Belgium.

But the Europeans had bankrupted themselves, both financially and morally, in two suicidal civil wars over the span of less than 40 years: World Wars One and Two. They would not be able to hold onto their colonies after the end of the War.

That meant that the colonies—representing more than 90% of all the nations on earth—would be in play. Most of them chafed under the yoke of Western imperial domination. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, promised them a means to get out from under such servitude.

It was going to be the greatest land grab in the history of the world, and the only plausible contenders for who would assume suzerainty over the developing world were the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

It is important to remember, too, that during the 1930s, which had immediately preceded the War, capitalist economies throughout the world had collapsed in the Great Depression. Industrial production plummeted, unemployment soared, and Western political systems approached instability. It was the Depression that gave rise to Adolph Hitler.

But Russia’s economy had boomed during this decade. Between 1929 and 1939, U.S. manufacturing output fell by 25%. However, Soviet output exploded, growing by almost 500%. This posed profound challenges to the viability of the Western economic system, and the legitimacy of Western leadership in the world.

Finally, it was not lost on U.S. leadership that the greatest industrial enterprise in the history of the world, World War II, had been won, not by the laissez faire economic system of the U.S., but by the top-down, command-and-control system of the Soviet Union. Allied victory was the greatest advertisement for the Soviet system that could have ever been contrived.

With all of these factors in play—east Asia, the Chinese civil war, the developing world, competing economic systems, and, of course, Japan itself—timing became critical.

The first considered landing for U.S. forces onto the Japanese home islands was not until November, more than three months out. The most likely invasion was not scheduled until January 1946, six months out. But the War now had to be ended not in months, or even weeks, but in days.

So, a uranium-based bomb, named Little Boy, was dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, two days before the Soviet Union was scheduled to enter the Pacific theater. A plutonium-based bomb, named Fat Man, was dropped on Nagasaki three days later.

Were they militarily necessary?

Dwight D. Eisenhower, future president of the U.S. stated, “Japan was already defeated and dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary.”

This was echoed by Admiral William D. Leahy, Chief of Staff to President Truman, who wrote, “The use of [the atomic bombs] at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender.”

According to Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, “The Japanese had, in fact, already sued for peace. The atomic bomb played no decisive part, from a purely military point of view, in the defeat of Japan.”

Major General Curtis LeMay commented on the bomb’s use: “The War would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb. The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the War at all.”

On August 14th, Japan announced its unconditional surrender. General Douglas MacArthur accepted the surrender in a ceremony on the battleship Missouri in Tokyo bay on September 2nd. The greatest war in the history of the world was over.

The U.S. now stood astride the world like a colossus amid pigmies. All of its traditional rivals had been destroyed in the War. The Soviet Union itself had suffered 26 million casualties, 90 times the number of losses for the U.S. The U.S. held more disproportionate power over all other nations than had ever occurred in the history of the world. This was the moment where the U.S. ideology of Exceptionalism was truly born.

Harry Truman, who had ordered the dropping of the bombs, clumsily tried to paste together a belated exculpation, claiming that he had saved the lives of as many as one million American soldiers, lives that would have been lost in an invasion of Japan. It was an entirely self-serving but vacant claim. There is no record of any such estimate in any documents of the armed services of the time.

The truth is that the atomic bombs were dropped on Japan, but they were used against the Soviet Union. Truman admitted as much when he later wrote that he had ordered their use partially “in order to make the Soviets more manageable.” It was the opening salvo in the Cold War which held the world in its menacing embrace for another 45 years.

What can this history tell us about today?

The U.S. is willing to use nuclear weapons even when they are not militarily necessary, to achieve its political and economic objectives. This becomes important today as China challenges the U.S. for economic primacy in the world, and as the U.S. stumbles with its own self-inflicted injuries incurred through the COVID 19 crisis.

In 2014, China passed the U.S. as the number one economy in the world in purchasing power parity terms. The date estimated for its passing in absolute terms was around 2025. But now, with the U.S.’s stumble, it is possible that by the time it finally emerges from the COVID debacle China will already be the largest economy in the world.

The psychic shock to the U.S. as it is displaced as the “number one country in the world” will be profound, partly because the people are not prepared for it, but also because the politicians appear not willing to even broach the possibility. We hear escalating rumblings about military efforts to “contain” China, up to and including the use of nuclear weapons and even full-scale war. These are idiocy.

Far better would be for the U.S. to examine the sources of its relative decline, and work to fix those. Those include the fact that it was U.S. corporations that eviscerated the industrial heart of America in order to establish lower cost operations in—wait for it—China. They include the fact that the U.S. has spent more than $6 trillion in the past two decades on fruitless wars in the Middle East, money that could have completely rebuilt its crumbling infrastructure.

They include the fact that the U.S. spends twice what other industrial nations spend on health care and gets inferior outcomes. If it only spent the average of what other industrial nations spend, it would free up some $2 trillion a year for reinvestment in building a more competitive, sustainable economy and a more just, inclusive society.

There’s one other perspective that might help us avoid an apocalyptic choice to use nuclear weapons again. It is tied up in the same reconciliation about racism that the U.S. is going through right now in response to the George Floyd killing.

The U.S. was born in a soil saturated with racism. That was simply the milieu of the times. And Hiroshima and Nagasaki could not have occurred without the same racism having informed the decision about using nuclear weapons on people deemed to be inferior.

But though the soil of the founding was rancid, the seed itself contained the germ of great ideals: that all men are created equal; that they possess natural rights that cannot be taken away; that they have the right to choose their own government; and that they have the right to be protected from abusive authority. Those ideals remain available to us, still, today. But only if we prove worthy of them.

The genetic DNA of America’s founding in a soil of racism and genocide cannot be extirpated, it cannot be changed. We carry it inside of ourselves, as part of who we are. But people and cultures are not plants. If you plant an avocado seed, you cannot expect to harvest peaches. But in the case of peoples and cultures, inherited traits can be changed.

The determinative facts of U.S. culture are not where it came from, but what its people do with the opportunities, values, and tools they have. They can rise above inherited racism and become the nation that its founders aspired to be, the one that still inspires noble action among people today.

The same applies to the learnings from Hiroshima. We cannot change what happened, neither the heinous military nor the tragic moral stains that indelibly mark its occurrence. But we can transcend it, rise above it, by naming it, acknowledging it, repudiating it, and committing ourselves to a greater expression of the people and society we imagine and hope ourselves to be. It is the only option for a sane, safe, and civilized future.

(Robert Freeman is the author of ‘The Best One Hour History’ series which includes World War I, The InterWar Years, The Cold War, and other titles. He is the founder of The Global Uplift Project which builds small-scale infrastructure projects in the developing world to improve humanity’s capacity for self-development.)