Research Unit for Political Economy

In the period since the emergence of Covid-19, the US has quite openly decided to use the crisis as a weapon against its perceived rival, China. As early as January 30, just days after the confirmation of human-to-human transmission of the virus, the US Commerce Secretary said that the disease, while “very unfortunate”, could prompt companies to reconsider operating inside China. This was not an off-the-cuff remark. The Commerce Department followed up with an emailed statement saying “It is also important to consider the ramifications of doing business with a country [i.e., China] that has a long history of covering up real risks to its own people and the rest of the world.”

On April 9, Japan announced that it would subsidize its firms if they moved their production base from China.[1] The European Union is preparing a report claiming that “China has continued to run a global disinformation campaign to deflect blame for the outbreak of the pandemic and improve its international image.”[2] The French President Macron has questioned China’s handling of the virus outbreak[3]. The European Commission chief has asked for an investigation into the origins of the virus.[4] And of course the US President has pressed US intelligence agencies to find the source of the virus, threatening in his distinctive manner to sue China $10 million for every US Covid-related death.[5]

This chorus has little to do with the virus, except its use as an opportunity. The process was underway well before Covid-19. The attempt to diversify global manufacturing chains away from China has been under discussion for the past two years, particularly in the wake of the US-China trade conflict.

A different type of globalisation

In the period 1990-2008, the globalisation of production proceeded at breakneck speed, and an estimated 70 per cent of global trade now involves global value chains. However, a special report by the Economist in July 2019 (long before Covid) found a “slow unravelling” of these chains:

A survey conducted in April [2019] of 600 MNCs around Asia by Baker McKenzie, an American law firm, found that nearly half of them are considering “major” changes to their supply chains, and over a tenth of them a complete overhaul. In many sectors this will mean a re-think of the role that China plays in sourcing.[6]

McKinsey Global Institute finds that global value chains in 16 of 17 big industries it has studied have become shorter, often moving production closer to the targeted consumer markets.[7] However, this does not necessarily mean an end to globalisation, but a shift in its pattern, for example, shifting production to other low-wage countries[8]:

The [US-China] trade war has also led to a re-think at Apple, which has reportedly asked its biggest suppliers to see how much it would cost to shift 15-30 per cent of its supply base out of China to South-East Asia or India.[9]

It is not easy for multinational firms to leave China; half the world’s electronics-manufacturing capacity is based there, and China offers unmatched advantages in infrastructure, skills, scale, and agility. Nevertheless, significantly, the Economist report concludes that

Mr Trump’s economic nationalism and attacks on China have won over America’s corporate elite…. There is bound to be an acceleration in the slow unravelling that is already under way of the complex supply chains that linked China to America.[10]

Huawei targeted

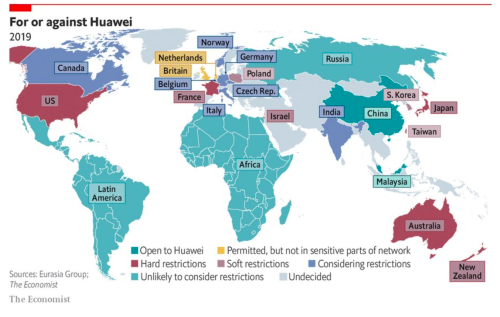

In 2019, more trade restrictions have been placed on China than on any other country.[11] Then, in the wake of the pandemic in 2020, a number of countries have placed restrictions on Chinese investment in their countries[12], as if in retaliation for the virus. A particular target of restrictions and bans has been the Chinese telecom giant Huawei.

Huawei, China’s largest private firm, is widely considered to have by far the best and cheapest 5G technology, which would in the normal course be installed throughout the world. Precisely for this reason, US pressure on Huawei has been intense: In December 2018, Canada arrested Meng Wanzhou, the chief financial officer of Huawei, on an extradition request from the US.

The UK, under US pressure, is now reconsidering its decision to involve Huawei in setting up its 5G networks; so is Germany.[13] The justification for the UK’s reversal on Huawei’s 5G is ‘security concerns’ – the possibility of China using Huawei 5G equipment to spy on western powers. But the actual commercial concerns are impossible to separate from the strategic motives. The drive to capture or retain markets and sources of raw material, and to deny them to one’s rivals, is in any case the staple of imperialist strategy.

The UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has now approached the US to form a ‘D-10’ club of ‘democracies’, consisting of the G-7 (the US, UK, Germany, France, Japan, Italy and Canada, with observer status for the European Union) plus Australia, South Korea, and India. The addition of the last three indicates that the grouping is focussed on China. The Times (London) reports that the first activity of this grouping would be to wrest markets from its rival:

One option would be to see the club channel investment to technology companies based within its member states. Nokia and Ericsson are the only European suppliers of 5G infrastructure and experts say they cannot provide 5G kit as quickly or cheaply as Huawei.[14]

Economist, July 13, 2019

The Economist predicts:

The Huawei fallout could lead to the bifurcation of global markets into two incompatible 5G camps…. In this scenario, Sweden’s Ericsson, Finland’s Nokia and South Korea’s Samsung would supply a pricier network comprised of kit made outside of China.[15]

Retaining global supremacy

For the US, there is also the broader objective of retaining global supremacy, on which rests the supremacy of the dollar as international currency. As Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist of the IMF, puts it, US “military dominance… has been one of the linchpins of the dollar”.[16] “NATO sets its sights on China”, says a recent Economist headline, reporting that the NATO Secretary-General Jens Stollenberg wants closer collaboration with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea in order to tackle China’s rise.[17] A detailed report in the same journal explains that this re-orientation will address the problem: “How can the transatlantic alliance hold together as America becomes less focussed on Europe and more immersed in Asia?”[18] According to a recent study,

The United States has led NATO to focus on China. Last August, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated that “China is coming closer” to Europe in the Arctic, Africa, investment in critical infrastructure, cyberspace, and investments in modern military capabilities. NATO’s London Declaration, following the December 2019 Leaders’ Meeting, was the first NATO declaration to mention China: “We recognize that China’s growing influence and international policies present both opportunities and challenges that we need to address together as an Alliance.” NATO is conducting an ongoing study, or “analysis exercise,” related to China that is, according to allied sources, looking into six main issues: cybersecurity; military deployments and Chinese military strategy; Afghanistan; Russia-China relations; Chinese investments in European critical infrastructure and strategic industries; and the impact of China on the rule-based global order.[19]

In March 2019, the European Commission termed China an “economic competitor” and “systemic rival”.[20]

The US and its allies apply pressure on a number of fronts simultaneously, both economic and political. The latest instance is that the US, UK, Australia, and Canada have expressed concern at China’s imposition of a national security law in Hong Kong. (Incidentally, among the personages expressing concern for ‘democracy in Hong Kong’, without any sense of irony, was its last colonial governor.)

- Indian government’s recent steps in relation to China

It is in this context that India has taken a number of steps in relation to China. As mentioned above, Boris Johnson wants India to be part of a group of 10 ‘democracies’ ranged, for all practical purposes, against China. The three instances sketched below – viz, checks on Chinese investment; the attempt to draw investment away from China; and the promotion of projects/sectors with specific anti-China protection; – show how India’s economic stances and policies are becoming more closely intertwined with its geopolitical stance.

i) Targeting China over Covid

India joined US-EU-Australian efforts to target China over Covid-19. This began with the Australian foreign minister demanding a ‘transparent’ global inquiry into the origins of the pandemic, including China’s handling of the initial outbreak in Wuhan. US Secretary of Health and Human Services Alex Azar, without naming China, said: “In an apparent attempt to conceal this outbreak, at least one member state made a mockery of their transparency obligations, with tremendous costs for the entire world.”[21] In May 2020, India won the chair of the World Health Organisation’s executive board, and immediately supported an EU-drafted resolution at the World Health Assembly (WHA) — the WHO’s decision-making body — for an investigation of the origins of the coronavirus. Under pressure, China conceded the demand.

On the face of it, who could object to such a probe, in the interests of world health? However, when the US and its allies press for such sweeping, open-ended exercises, their motive has nothing to do with the purported subject matter, and everything to do with strategic-military aims with regard to the investigated country. One has only to recall the unending search for weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and the unending investigation of Iran’s nuclear programme.

ii) Check on Chinese investment in India

In May, India announced that, hereafter, any foreign direct investment (FDI) from a country with which it shares land borders would require Government approval. Since Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Bhutan and Burma are not investing in India, the regulation was targeted solely at China. Earlier, FDI approval was automatic except in select strategic sectors. The Government clarified that this change was in order to curb “opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies due to the current COVID-19 pandemic” (emphasis added).[22]

The online journal Swarajya, which generally voices the RSS viewpoint, clarified that “As the global slowdown pushes share prices of companies down, China is looking to go on a shopping spree in the season of an induced artificial sale…. it is in the best interests of India to learn from its counterparts in Europe who have been late to realise the economic, social, and political magnitude of Chinese investments in the region.”[23]

Since this bar effectively applies only to China, it becomes clear that opportunistic takeovers/acquisitions of Indian companies by other countries, such as the US, Japan, or the EU, have the Government’s approval. As we saw in a previous article (published in Janata, June 7, 2020), there is in fact a ‘pandemic’ of such opportunistic takeovers by non-Chinese foreign investors in the wake of India’s corporate debt crisis.

iii) Wooing global investors away from China, in coordination with Western powers

While portraying Chinese investment in India as a form of “opportunistic takeover”, the Indian government has been single-mindedly focussed on luring global investors away from China. On April 28, the Prime Minister told chief ministers to get their states ready for this task, and on May 1 he held a meeting with top ministerial colleagues on May 1 “to capture a part of the supply chain that is expected to move out of China as global corporations look to diversify their production base in the aftermath of Covid-19.” [24]

According to transport minister Nitin Gadkari, China’s weakened global position is a “blessing in disguise” for India to attract more investment. Bloomberg reports that India is readying a pool of land twice the size of Luxembourg to offer companies that want to move manufacturing out of China, and has contacted 1,000 American multinationals.[25] A paper prepared for the Ministry of Commerce and Industry quivers with anticipation: “Such diversification and shifting of Japanese firms away from China is estimated to create a $730 billion economic opportunity for developing geographies like ASEAN and India. The ongoing COVID-19 crisis presents a golden opportunity for India and Japan to further boost their already successful relationship.”[26] (Pursuing “golden opportunities”, evidently, is different from being “opportunist”.)

For foreign investors planning to invest in industrial production, the availability of cheap/free land, state-of-the-art infrastructure, and a healthy, educated workforce – actually forms of State subsidies to private capital – are major considerations. These they have long enjoyed in China. Cheap or free land may be provided by the Indian government (by removing it from the hands of the peasantry), but, given the state of India’s infrastructure and the physical and educational status of its workforce, the Indian rulers’ breathless pursuit of foreign investment exiting China may never yield the results they hope for.

Nevertheless this objective is being pursued in all earnest, not only by India, but at the level of the leading Western powers and Japan as well. David Arase, resident professor of international politics at the Johns Hopkins University Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies, says:

There is obvious scope for US-Japan cooperation if leaders decide to coordinate their supply chain adjustment efforts with Indo-Pacific policy agendas. For example, India is regarded by both the US and Japan as a key strategic and economic Indo-Pacific partner that could benefit from better economic connectivity with the advanced West.[27]

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that the Trump administration was ‘trying to mesh the supply chains that both countries (India and the US) have access to.’” According to a State Department official, “We’ve been working on (reducing the reliance of our supply chains in China) over the last few years but we are now turbo-charging that initiative.”[28]

The United States is pushing to create an alliance of “trusted partners” dubbed the “Economic Prosperity Network,” one [State Department] official said. It would include companies and civil society groups operating under the same set of standards on everything from digital business, energy and infrastructure to research, trade, education and commerce, he said.

The US government is working with Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea and Vietnam to “move the global economy forward,” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said on April 29.

These discussions include “how we restructure … supply chains to prevent something like this from ever happening again,” Pompeo said.[29]

The phrase “Economic Prosperity Network” uncannily echoes the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”, the term Japan used for the countries it occupied during 1931-45.

iv) Trade barriers on Chinese goods

Under the banner of ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (self-reliant India), the Government now plans to impose higher trade barriers such as licensing requirements or stricter quality checks on 100 products, and additional import duties on around 160-200 products.[30] Although the measure purportedly does not target any country, the Government has selected these commodities after a process of collecting information regarding imports from China:

The industry has been asked to send comments and suggestions on certain number of goods and raw materials imported from China, which include wrist watches, wall clocks, ampoules, glass rods and tubes, hair cream, hair shampoos, face powder, eye and lip make up preparations, printing ink, paints and varnishes, and some tobacco items…[31]

The New York Times comments favourably on these trade barriers against China, and adds that “Diplomats expect India to prevent the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei from entering its market to build a 5G wireless network.”[32]

Many more instances could be added to the above list of Indian industries which are unable to face competition from China (for example, toys, locks, and firecrackers). These industries deserved protection from cheap imports, Chinese or otherwise, long ago; some of them have been almost wiped out, and it may now take more than tariff protection to revive them. Perhaps the Government hopes to garner support from small and medium industries in India, which have been bearing the brunt of this competition. Indeed, the Modi government has always been alive to such political calculations.

However, as we saw in the previous article, small and medium industries in India face a grim future, due to the collapse of domestic demand. In the absence of a systematic plan for self-reliance, and the building of a range of domestic capabilities, linked crucially to a widely dispersed increase in domestic demand, the imposition of trade barriers against China will bring about no generalised improvement in the situation of small and medium industries in India. These trade barriers might result only in the effective reduction in the purchasing power of Indian consumers, by making a range of cheap manufactured goods more expensive.

v) New policy stance in practice: The case of Adani’s solar power project

On the other hand, the anti-China policy stance might yield profitable opportunities for certain favoured Indian corporate groups and Western/Japanese multinationals. The latter have in recent years faced stiff competition in India from Chinese firms in high-tech sectors such as telecom equipment, power equipment, and high-speed trains. The Chinese firms’ prices are much lower, and their quality is said to be comparable, and in some cases (such as 5G telecom equipment) superior.

Take the solar power related manufacturing sector, where China is overwhelmingly dominant, producing 80 per cent of solar cells worldwide and 72 per cent of the modules. It enjoys huge economies of scale, with prices dropping substantially every year. India’s local photovoltaic manufacturing sector has failed to compete with China, not only on price, but on quality. Nor is it alone. While the US’s higher prices are said to be partly compensated by quality, the leading German firm in the field simply wound up its own production in 2013.[33]

The Indian government is now planning to provide import protection for solar-related manufacturing firms based in India, with additional customs duties on solar modules and cells, a guaranteed flow of subsidised power, and financial subsidies (cheap credit and ‘viability gap funding’ – a fancy name for a government subsidy given to corporate firms).

Made-in-India solar panels may not be the most competitive. What may work in India’s favor, however, is the strategic shift in the priorities of companies and countries post Covid-19: comparative costs have ceased to be the only criterion for deciding on equipment supply.[34]

This is unlikely to bring about ‘self-reliance’, however, in the form of Indian firms developing their technological capability to manufacture modules, cells and other equipment cheaply and well. Rather, it is likely to mean inviting non-Chinese foreign firms to invest here, protecting them from Chinese imports, and providing them subsidies:

India’s push could be led by government-owned companies like Bharat Heavy Electricals, which invited international players last month to leverage its “facilities and capabilities” — 16 manufacturing locations, a substantial landbank, and 34,000 employees — to set up base in India.[35]

On June 9, the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) awarded the Adani group (one of the corporate groups most closely linked to the present regime) the world’s largest solar energy tender: to build 8 GW of photovoltaic power plant along with a domestic solar panel manufacturing unit at an investment of Rs 45,000 crore. Adani share prices have doubled since the start of the year.

Such projects are financially impossible for even the officially-favoured Adani group to execute on its own. Labeled one of India’s top 10 over-indebted groups in 2012, its debt has since doubled, reaching Rs 1.28 lakh crore by 2019. In the last two years, the group has preferred to borrow offshore, with foreign borrowings now accounting for 30 per cent of its debt. Foreign currency bonds in particular doubled from 14 per cent of total debt to 25 per cent between March 2016 and March 2019.[36] Any sharp depreciation of the rupee should spell trouble for the group, but it leads a charmed existence, seemingly certain that its bets will be winning ones.

The group’s growth has been closely linked to Government favours and contracts, particularly with the Gujarat government till 2014, and since then the Central government. “The group’s listed companies saw their value rise by some 85 per cent soon after Modi’s inauguration, compared to a roughly 15-percent increase for the Sensex over the same period. Within a year of Modi’s term at the centre, the companies’ market value had risen by over Rs 50,000 crore.”[37] The Adani group entered solar power in 2013 with a 40 MW project in Gujarat, and has bet heavily on solar power since then. Winning the latest solar tender is thus not a surprise: “SECI enjoys the full support of its 100 percent owner, the government of India,” said Adani Green’s spokesperson.[38]

As in the rest of the Government’s ‘self-reliance’ schemes, this exercise may provide profit-making opportunities to (non-Chinese) multinationals while at the same time ensuring that favoured Indian corporate groups thrive. Boasting that his group is the only Indian business house with a series of 50:50 ventures with international players such as Total and Wilmar, Adani revealed that he is in discussion with potential equity and strategic partners for solar equipment manufacturing.[39]

The scheme is directly linked to shutting out China: Adani claims that, with his solar projects, “The 90 per cent import of Chinese equipment will fall to 50 per cent, and ultimately zero. In 3-5 years, it will be negligible.” [40]

In February this year, Adani hived off several gigawatts of operational solar assets into a new company, with French energy major Total taking a 50 per cent stake in the new venture for $510 million – part of the rush of global oil and gas giants into the ‘renewable’ energy market.[41] The Indian government has set a far-fetched target of 100 GW (i.e., 100,000 MW) of solar power by 2022, but capacity at end-2019 was only 36 GW. There are big bucks to be made in the sector in the coming years. Adani said Total was “very much interested” in expanding its partnership with Adani Green, as are other foreign investors. The firm’s spokesperson said that “[Adani Green] is always looking for ways to further reduce its costs of capital and to work with other energy majors and traditional investors as a path to facilitating the company’s continued rapid growth.”[42]

Some caveats

The above is a description of the manner in which the geopolitical drive against China, led by the US and drawing in India, advances, and intertwines with, certain economic interests. It does not signify that multinationals will withdraw from China overnight, or that India can discontinue its imports from China, or that India will be the recipient of all the investment that exits China. (Nor does it signify that, even if India were to receive a flood of foreign direct investment, it would constitute a positive development; but we will address that point later.)

For Western multinationals, China’s infrastructure, clustering of firms, scale of production, subsidies, educated workforce, agility in carrying out production changes and delivering on time, are in many cases without parallel. Though China’s labour costs have risen, they remain a fraction of those in the US or even Mexico. Firms from US and other developed countries have large sunk investments in China. All these mean that a shift from China may take time, and may vary from sector to sector.

Nevertheless, holding out to India the prospect of large investments shifting from China helps to orient India more closely to US foreign policy, whether or not much investment finally materialises.

For India, too, an immediate break in trade with China does not appear practicable. China was India’s largest trading partner from 2013-14 to 2017-18. Though the US appears to have taken that position since then, China remains a major trade partner. It runs a large trade surplus with India, supplying the entire range of manufactured goods from low-tech to high-tech, while India exports, in the main, low-value-added raw materials to China. Chinese investments in India are concentrated in the prominent e-commerce sector, in firms such as Ola, Paytm, Zomato, Flipkart, and Byju’s. Reportedly, two-thirds of ‘unicorns’ – start-ups valued at $1 billion or more – have Chinese investment.[43] Dependence on China is overwhelming in some sectors, such as in health-related goods: 90 per cent of basic drugs are imported from China, with Indian firms restricting themselves to making formulations from these drugs.[44]

As such, it would appear that it is much harder for India to disentangle itself from China than the for the latter to do without India. Nevertheless India is clearly taking steps which will set it on a collision course with China.

- India as part of a coalition against China: the “Indo-Pacific” catch phrase

This can be seen most clearly at the strategic plane. In recent years, India has unmistakably become a member of a coalition of powers targeting China. The catch phrase of Indian diplomacy in recent years has been “Indo-Pacific”, signifying that India views its strategic interests as extending to at least the South China Sea.

Some recent examples:

• India’s Prime Minister informed his Japanese counterpart in November 2019 that “India’s relationship with Japan is a key component of its vision for peace, prosperity and stability in the Indo-Pacific region”.

• During the visit of India’s defence and external affairs ministers to Washington in January 2020, the two sides “reaffirmed their commitment to support ‘a free, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific region’.”

• On June 4, 2020, the Prime Minister held a ‘virtual summit’ with the Prime Minister of Australia, and issued a “Shared Vision for Maritime Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific”.But it is make-believe to claim that India’s security interests stretch up to the Pacific Ocean. It is, rather, the Indian rulers’ dreams of great-power status that stretch far beyond India’s borders, and far beyond India’s material base (military and economic). The scale of these ambitions is reflected in the writings of the widely-published strategic commentator (former member of India’s National Security Advisory Board), C. Raja Mohan, who views India as the heir of the British Raj:

The Raj was the principal provider of security in the region stretching from Aden to Malacca and Southern Africa to South China Sea. If the Royal Navy established total dominance over the waters of the Indian Ocean and its approaches, the Indian Army was the sword arm of the Raj in ensuring stability in the vast littoral….

Independent India’s opposition to intervention of other powers in its periphery, security assistance to smaller neighbours, and the claim of a security perimeter running from Aden to Malacca are rooted in the definition of territorial India’s defence imperatives under the Raj… like the Raj, India is emerging as one of the important military powers in Asia and the Indian Ocean and there appears to be new political will in Delhi to see itself as a regional security provider.[45]

It is of course not India, but the US, that is heir to the Raj as the hegemon of the region. Nevertheless it suits the US that the Indian rulers nurse such notions, since they need India as a junior partner.

The current use of the phrase “Indo-Pacific”, in discussion of diplomatic and strategic affairs, in fact originates in the US State Department. Then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton

first used the term “Indo-Pacific” in 2010 to reflect closer naval cooperation with India; “we are expanding our work with the Indian navy in the Pacific, because we understand how important the Indo-Pacific basin is”. Whereas US relations with Australia had previously been described and conducted within an “Asia-Pacific” framework, Clinton extended this with “Indo-Pacific” references; “we are also expanding our alliance with Australia from a Pacific partnership to an Indo-Pacific one”.[46]

Japan coined the expression ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ in 2016, and Trump embraced ‘the framework’ in 2017.[47] In 2018, a US State Department official spelled out the reasons for using the term “Indo-Pacific”:

It’s significant that we use this term. Before, people used the term Asia Pacific […] but we’ve adopted this phrase… it is in our interest, the US interest, as well as the interests of the region, that India play an increasingly weighty role in the region…. It is a nation that can bookend and anchor the free and open order in the Indo-Pacific region, and it’s our policy to ensure that India does play that role.[48]

In May 2018, the US Defense Secretary announced that the US Pacific Command had been renamed the “Indo-Pacific Command”, “in recognition of the increased connectivity of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.”

Why the US promotes India’s great-power ambitions [49]

Shortly after Clinton introduced the “Indo-Pacific” concept, it was retailed in India by retired top bureaucrats and military men such as former Navy chiefs Arun Prakash and Suresh Mehta, and the influential former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran (later special envoy for Indo-US civil nuclear issues, and chairman of the National Security Advisory Board). Within a few years it became ubiquitous, with the Prime Minister, External Affairs Minister, and foreign secretary adopting it.

The US’s motivation in promoting the “Indo-Pacific” concept is, by contrast with India’s, clear and grounded in reality. A report commissioned by the US Department of Defence in October 2002, titled The Indo-US Military Relationship: Expectations and Perceptions[50], noted that

[American officers] are candid in their plans to eventually seek access to Indian bases and military infrastructure. India’s strategic location in the centre of Asia, astride the frequently traveled Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC) linking the Middle East and East Asia, makes India particularly attractive to the US military.

A 2005 US War College study, which draws on discussions its author had with representatives of different military services at the US Pacific Command, states bluntly:

We need tangible Indian support because our strategic interests and objectives are global, while the military and other means at our disposal to pursue them are not keeping pace…. American force posture remains dangerously thin in the arc – many thousand miles long – between Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean and Okinawa and Guam in the Pacific…[51]

The Indian public, however, are unaware that their country may be made the linchpin of a broader US-sponsored military alliance for Asia:

during 2003, if not since then, American and Indian officials discussed a possible ‘Asian NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organisation)’ although the content of these discussions and of India’s significance for them has not been made public.[52]

Integrating India into the US strategic order

The process of integrating India with US strategic planning was well under way during the UPA government (2004-14), but has proceeded much faster under the Modi government. In 2016 India signed the Logistics Exchange Memorandum of Agreement (LEMOA) with the US, which allows each country to use specified military installations of the other country for certain purposes. (A similar deal was concluded in June 2020, during the virtual summit between Modi and the Australian Prime Minister.) India has signed other agreements with the US for secure encrypted communication between the two armed forces and transfer of technology, and is turning increasingly to the US for military equipment. US arms sales to India rose by more than five times during 2013-17 compared to the previous five years.[53]

The integration of the two militaries is fairly advanced; the two sides have conducted the largest number of joint military exercises between the US and a non-NATO member. In November 2019, India and the US held their first joint tri-service military exercise (a joint land, air and sea exercise) in coastal Andhra Pradesh.[54] The US and Indian navies jointly track Chinese submarines in the Asia-Pacific region.[55] According to one analyst, “The U.S. now accords India almost the same status that it gives NATO member states.”[56]

India is also tasked with building ties with a number of countries in the region, including Indonesia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Singapore, and Philippines. There is little attempt now to conceal the fact that these efforts are targeted at China. Australia may participate in the annual Malabar Exercises in 2020, along with the US, Japan, and India.[57] The Indian navy recently sailed with the US, Japanese, and Philippine navies through disputed waters in the South China Sea.[58] India and Indonesia have concluded an agreement to develop and manage the Sabang port, located close to the strategic Malacca Straits, through which shipping passes to China.[59]

At the political level, India, the US, Japan and Australia are the four members of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad for short. At the inception of this process in 2007, China protested that it was a nascent anti-China alliance, and India put it on the back burner. However, since 2017, the Quad has been revived, and in September 2019 the foreign ministers of all four member countries met in New York – a significant escalation. In January, India held a “2+2” meeting with the US, that is, India’s external affairs and defence ministers met their US counterparts. This is a format that the US reserves for its close allies.[60]

Against India’s interests

However, none of this makes sense from the angle of India’s own security. On the contrary, it entangles India in distant adventures, and threatens to thrust India into wars which serve US, not Indian, interests. If India were to pursue its true national interest, it would see through the US’s intentions in labeling it a “great power”, and immediately disengage from these warlike alliances.

Such a clear-headed view of India’s national interest would endanger the entire “Indo-Pacific” enterprise of the US. Only when India imagines itself as a great power, a “counterpoise to China in the region”, would it want to promote a broad anti-China alliance. And so the US must promote this dream of the Indian rulers. As the US War College study earlier cited points out,

But crucial to making this system [i.e., an anti-China coalition including India] work is India’s being convinced of its ‘manifest destiny’and for it to act forcefully. It will require in the main that New Delhi think geostrategically and give up its diffidence when it comes to advancing the country’s vital national interests and its almost knee-jerk bias to appease friends and foes alike. The corrective lies in the Indian government expressly defining its strategic interests and focus and, at a minimum, proceeding expeditiously towards obtaining a nuclear force with a proven and tested thermonuclear and an ICBM reach. Nothing less will persuade the putative Asian allies that India can be an effective counterpoise to China in the region, or compel respect for India in Washington.[61]

In line with this aim, the US now terms India a “leading global power”. The US National Security Strategy of 2017 states: “We welcome India’s emergence as a leading global power and stronger strategic and defense partner.”

Evidently, China too views India as a defence partner of the US, and as part of an anti-China coalition. It has decided to respond, not in the South China Sea, but closer to India.[62] Grim consequences have already ensued, and there are portents of worse to come.

Realizing the goal of “an India closer to the West”

Seen in this light, the growing hostility between India and China since the emergence of Covid-19, culminating in the clashes between the two armies at the Line of Actual Control, serves the needs of the US’s grand strategy for the region. With remarkable candour, the New York Times greets the recent border clashes with enthusiasm, as the final step in India’s journey towards an anti-China alliance with the West:

For years, the United States and its allies have tried to persuade India to become a closer military and economic partner in confronting China’s ambitions, painting it as a chance for the world’s largest democracy to counterbalance the largest autocracy. This week, the idea of such a confrontation became more real as Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed…

With China facing new scrutiny and criticism over the coronavirus pandemic, Indian officials have recently seemed emboldened, taking steps that made Western diplomats feel that their goal of an India closer to the West was starting to be realized. And some believe the friction with China will push India even further in that direction.

One Western diplomat felt that the coronavirus crisis had made India more eager to build stronger relationships to help it deal with China, and that diplomacy with India was going more smoothly than ever before. “Everyone is more willing, privately, to talk about what to do with China in a post-Covid world,” the diplomat said.

Mr. Gokhale, the former Indian foreign secretary, said that countries could no longer ignore Beijing’s transgressions and must choose between the United States and China.“In the post-Covid age,” he wrote, “enjoying the best of both worlds may no longer be an option.”[63]

Truly, Covid-19 has become a useful peg on which to hang any number of agendas which have nothing to do with the health of the people.

References

[1] Mercy Kuo, interview with David Arase, “Japan prods firms to leave China, affecting ties with Beijing and Washington”, The Diplomat, May 8, 2020.

[2] “As China pushes back on virus, Europe wakes to ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy”, Reuters, May 14, 2020.

[3] “Coronavirus: Macron questions China’s handling of outbreak”, BBC, April 17,2020.

[4] Silvia Amaro, “EU chief backs investigation into coronavirus origin and says China should be involved”, CNBC, May 1, 2020.

[5] Steven Erlanger, “Global Backlash Builds Against China Over Coronavirus”, New York Times, May 3, 2020.

[6] “Special report: Global supply chains”, Economist, July 13, 2019, p. 4.

[7] Ibid., p. 5.

[8] Some production may also be ‘re-shored’ to the US, either if it is highly automated, or if US wage levels fall to much lower levels in the wake of the current depression and the re-structuring of labour in the US.

[9] Ibid., p. 5.

[10] Ibid., p. 11.

[11]Nikita Kwatra, “Why falling for anti-China mood could hurt trade”, Mint, June 4, 2020.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Jonathan Shieber, “UK government reverses course on Huawei’s involvement in 5G networks”, Tech Crunch, May 24, 2020.

[14] Lucy Fisher, “Downing Street plans new 5G club of democracies”, The Times, May 29, 2020.

[15] “Special report: Global supply chains”, p. 11.

[16] Kenneth Rogoff, “America will need $1,000 billion bail-out”, Financial Times, September 17, 2008.

[17] Economist, June 6, 2020.

[18] “How NATO is shaping up at 70”, Economist, March 19, 2019.

[19] Andres Ortega Klein, “The US-China Race and the Fate of Transatlantic Relations, Part II: Bridging Differing Geopolitical Views”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 23, 2020.

[20] “EU-China – A strategic outlook,” European Commission, March 12, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf, cited in Klein, op. cit.

[21] Shubhajit Roy, “WHO nod for coronavirus probe, China backs down”, Indian Express, May 19, 2020.

[22] Sunanda Sen, “New FDI Norms in Time of Covid – Good Economics or Geopolitics?”, The Wire, May 2, 2020.

[23] Tushar Gupta, “Restricting Chinese FDI into India: How China Uses Financial Crisis to Further Its Expansionist Agenda”, June 18, 2020.

[24] “Covid-19: PM Modi signals push to attract firms that exit China to India”, Times of India, May 1, 2020.

[25] Nikhil Inamdar, “Coronavirus: Can India replace China as world’s factory?”, BBC News, May 18, 2020.

[26] “Invest In India: Govt Pitches For Japanese Companies As They Move Out Of China”, IANS, May 14, 2020.

[27] Mercy Kuo, op. cit.

[28] “Trump administration pushing to rip global supply chains from China: officials”, Reuters, May 4, 2020.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “India Plans Higher Trade Barriers, Raised Import Duties on 300 Foreign Products: Report”, Reuters, June 18, 2020

[31] “Amid Border Tension, PMO Seeks Product-Wise Details from India Inc to Curb China Imports”, News18, June 21, 2020.

[32] Maria Abi-Habib, “Will India Side With the West Against China? A Test Is at Hand”, New York Times, June 19, 2020.

[33] Christoph K. Klunker, “Let China pay for India’s solar push”, Mint, August 9, 2018.

[34] Vandana Gombar, “Taking on China in solar manufacturing”, Business Standard, June 9, 2020.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Aman Kapadia, Forum Bhatt, “Adani Group’s growing debt pile is changing colour”, Bloomberg Quint, November 5, 2019. https://www.bloombergquint.com/bq-blue-exclusive/adani-groups-growing-debt-pile-is-changing-colour

[37] Nileena MS, “The Massive Indebtedness of the Adani Group and Its Convenient Relations with Government Enterprises” Caravan, March 15, 2018, https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/extract-cover-story-massive-indebtedness-adani-group-convenient-relations-government-enterprises

[38] John Parnell, “India’s Adani wins world’s largest solar tender”, Green Tech Media, June 10, 2020, https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/adani-awarded-worlds-largest-solar-tender-win

[39] “Solar equipment imports from China will fall to zero in 3-5 years, says Gautam Adani”, ET Now Digital, June 10, 2020.

[40] Ibid.

[41] John Parnell, “Total and Shell give green lights to big power investments in India and Australia”, Green Tech Media, February 6, 2020.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Zia Haq, “From infrastructure to hi-tech: Mapping China’s large trade footprint in India”, Hindustan Times, June 19, 2020.

[44] Ibid.

[45] C. Raja Mohan, “India as a Security Provider: Reconsidering the Raj Legacy”, ISAS Working Paper, National University of Singapore, March 2012.

[46] David Scott, “The Indo-Pacific in US Strategy: Responding to Power Shifts”, Rising Powers Quarterly, vol. 3, Issue 2, 2018.

[47] Ibid.

[48] “The Indo-Pacific Strategy”, speech byAlex Wong, Deputy Assistant Secretary in the East Asian and Pacific Affairs Bureau at the State Department, April 2018, cited in Scott, op. cit.

[49] The following draws on our earlier study, Global Power, Client State: India’s Place in the US Strategic Order, 2005. The relevant passage can be found at https://www.rupe-india.org/41/why.html

[50] Josy Joseph, a series of six articles beginning with “Target Next: Indian Military Bases”, April 21-26, 2003, www.rediff.com.

[51] Stephen J. Blank, Natural Allies? Regional Security in Asia and Prospects for Indo-American Strategic Cooperation, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College, September 2005, p. 13. (www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pubs/display.cfm?PubID=626).

[52] Blank, op. cit., p. 1.

[53] John Cherian, “US and India: Strengthening ties”, Frontline, January 17, 2020.

[54] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiger_Triumph

[55] Ibid.

[56] Cherian, op. cit.

[57] Sandeep Unnithan, “Modi-Morrison summit: How Beijing’s belligerence makes the ‘Quad’ more attractive for New Delhi”, daily O, June 15, 2020 https://www.dailyo.in/politics/modi-scott-morrison-virtual-meet-india-china-border-tension-india-australia-ties-2020-malabar-naval-exercise/story/1/33113.html

[58] Ankit Panda, “US Navy Ship Replenishes Indian Navy Ship in South China Sea”, The Diplomat, November 6, 2019.

[59] Saurabh Todi, “India gets serious about the Indo-Pacific”, The Diplomat, December 18, 2019.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Blank, p. 79.

[62] Pravin Sawhney of Force India reveals that, during the second informal summit between Xi Jinping and Modi at Chennai on October 11-12, 2019, the former proposed a trilateral cooperation between China, Pakistan and India to address contentious issues. This was in the wake of the change in status of Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh. The Indian side rejected this proposal. See “Facade of Equal Security Collapses in Ladakh”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AZSbpk5iZGk

[63] Maria Abi-Habib, op. Cit.

(Research Unit for Political Economy is a trust based in Mumbai that brings out material seeking to explain day-to-day issues of Indian economic life in simple terms and link them with the nature of the country’s political economy.)