(Note: Most readers will have seen this article. We had posted it earlier on our mailing list. We are printing it here to formally include it in the magazine.)

Ever since the Modi Government came to power in 2014, it has been claiming that its economic policies have made India one of the fastest growing large economies in the world. It made this claim in the Economic Survey 2018–19, and again in the Economic Survey 2019–20. Then, the corona pandemic struck, and the Modi Government’s gross mismanagement of the pandemic pushed the economy into an unprecedented collapse, one of the worst in the world.

But the very next year, the Economic Survey 2020–21 again claimed that “India is expected to be the fastest growing economy in the next two years.” This year, the Economic Survey 2023–24 declares India to be the fastest growing G-20 country. It estimates the Indian economy to have grown at 8.2 percent in real terms in 2023–24. This high rate of growth “came on the heels of growth rates of 9.7 percent and 7.0 percent, respectively, in the previous two financial years.”[1]

India’s GDP is estimated to have reached $3.6 trillion in 2024. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman expects India to become a $5 trillion economy by 2027–28 or thereabout[2], and the finance ministry’s review of the Indian economy released in January 2024 says that India should become a $7 trillion economy by 2030.[3]

The Prime Minister’s Yes-men-and-women have been competing with each other in making even grander claims, of India becoming a $10 trillion and a $20 trillion economy in the years and decades to come. NITI Aayog has made a triple jump, and come out with a draft vision document Viksit Bharat @ 2047 to make India a $30 trillion economy by 2047.[4] The Economic Survey 2023–24 posits: “India … has now set for itself the goal of becoming a developed nation within a generation by 2047, the hundredth year of independence.”[5]

Modi’s friends are excitedly chirping in unison. Business tycoon Gautam Adani has come up with this gem, “Following independence, it took us 58 years to get to our first trillion dollars of GDP, 12 years to get to the next trillion and just 5 years for the third trillion. I anticipate that within the next decade, India will start adding a trillion dollars to its GDP every 18 months. This puts us on track to be a $25–$30 trillion economy by 2050 …” Mukesh Ambani has gone one step further, and said that he expects India to become a $35 trillion economy by 2047.[6]

All these buffoons are also gung-ho about India being the fifth largest economy in the world, and becoming the third largest economy in a few years.

But in an economy with such extreme inequality — India is now among the most unequal countries in the world, with the top 1 percent controlling more wealth more than during the British colonial period, while the majority of the population lives on incomes among the lowest in the world [7] — such overall figures have no meaning. The same IMF, which expects India to become a $5 trillion economy by 2026–27, also admits that India had the lowest per capita income among all large economies. In per capita terms, the Indian economy is at the 138th position in the world.[8] Being the fifth or the third largest world economy is of no consolation to the marginalised.

This means that there is a problem with the very assumption that GDP is a measure of societal well-being, and that a high GDP growth rate would increase employment, increase wages and lead to reduction of poverty. This problem has got particularly accentuated in the neoliberal era, when giant corporations have come to dominate the economy, and growth only means growth in their profits, growth in wasteful consumption of the rich, and boom in the stock market, all of which are accompanied by destruction of livelihoods of common people and ruination of the environment. This has also been pointed out by the Stiglitz Commission, set up by the President of France some time ago to identify the limits of GDP as an indicator of economic performance and social progress, including the problems with its measurement. The report of the Commission, authored by two of the world’s most renowned economists, Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen, notes that over the course of recent decades, GDP was rising in most of the world, even as the median disposable income was falling in many countries, meaning that economic growth was benefiting the wealthy at the expense of the rest. The Stiglitz Commission report calls on policy makers to focus on the material well-being of typical people by measuring income and consumption, along with the availability of health care and education, instead of being obsessed with GDP growth rates.[9]

But let us keep this issue aside. In this chapter, we subject the official GDP and GDP growth rate figures released by the official statisticians of the Modi government to close scrutiny. The investigation reveals several problems with the data and methodology, which raise questions about the reliability of these figures.

Problem 1: Manipulation of Data

Even a cursory look at the GDP data released by the Modi Government reveals that it has no qualms about manipulating data to suit its political propaganda!

India had one of the best and most reliable statistical systems in the developing world. The Modi Government has ruined it. It has curbed the independence of the National Statistical Commission — which was originally envisaged as an independent body of experts which would verify and supervise the collection, collation and dissemination of official data — and made it subservient to its wishes. It has pressurised the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO), the body that collects and disseminates data, which is run and staffed by professional economists and statisticians, to blatantly manipulate data to glorify the economic record of the Modi Government. This coercion began immediately after the Modi Government came to power in 2014.[10] We present below a brief summary of how the country’s official statisticians have doctored GDP data in accordance with the desires of their masters.

Soon after the Modi Government assumed power, in early 2015 the CSO announced that it was changing the base year for all calculations to 2011–12 (from the earlier base year of 2004–05), as well as changing the methodology for calculating the GDP. Based on this, it came out with new figures that magically upped the GDP growth rate to 7.5 percent year-on-year during the third quarter (October–December 2014), overtaking China’s 7.3 percent growth in the same quarter, making India the fastest growing major economy in the world. The CSO also forecast the full year GDP growth for 2014–15 to accelerate by nearly 2 percentage points to 7.4 percent, from the 5.5 percent estimated earlier by the old method. The following year (2016), the CSO projected the country’s growth rate to further accelerate to 7.6 percent for the year 2015–16 (see Table 1.1 for the two sets of figures).[11]

Table 1.1: GDP Growth Rate Figures, 2014–15 and 2015–16

| 2014-15 | 2015–16 | |

| GDP Growth Rate ¹ | 7.4 | |

| GDP Growth Rate ² | 7.2 | 7.6 |

¹ Advanced Estimate, February 2015;

² Advanced Estimate, February 2016.

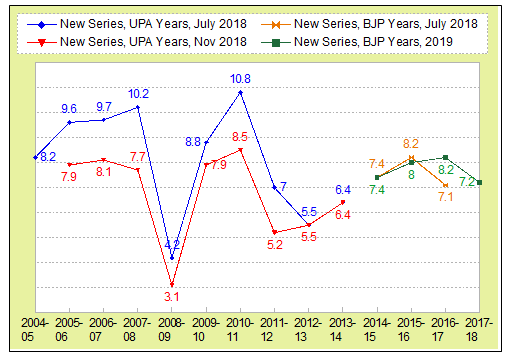

Now, there is fundamentally nothing wrong with re-basing the GDP; this is periodically done. But this time, there were several reasons for doubting the new data series. To begin with, whenever the GDP is rebased, the “back series” is also released immediately, going back to at least a decade or more. This time, what was bewildering was that for three years the CSO did not publish GDP growth figures for the years prior to 2011–12. Finally, in July 2018, a committee set up by the National Statistical Commission (NSC) presented its estimates of GDP back series based on the new methodology. But to the Modi Government’s dismay, the new back series showed that economic growth during the UPA years exceeded the growth during the Modi years. The new series calculated the average growth rate during the UPA years to be 8.0 percent, while the average growth rate during the 3 BJP years as per the new series was 7.6 percent. Despite the NSC being an autonomous body, the Modi Government forced the NSC to trash the report, and the government’s sycophantic statisticians burnt the midnight oil to come up with a new back series that showed a lower rate of growth during the UPA years as compared to the BJP years. The new data now lowered the growth rate during the UPA years to 6.7 percent. And then, wonder of wonders, in 2019, just a day before the Modi Government released the last budget of its first term, the CSO further bumped up the growth rate data for the year 2016–17 to show that growth for the four BJP years was even higher than earlier projected, at 7.7 percent (Chart 1.1 and Table 1.2).[12]

Chart 1.1: GDP Growth Rates, New Series: July 2018, Nov. 2018 and 2019

(constant prices, 2011–12 base, %)

Table 1.2: GDP Figures : 2018 and 2019 Series

(constant prices, 2011–12 base) (%)

| Average GDP Growth rate | July 2018 series |

| 2005–06 to 2013–14 (UPA Years) | 8 |

| 2014–15 to 2016–17 (BJP Years) | 7.6 |

| Nov 2018 series | |

| 2005–06 to 2013–14 (UPA Years) | 6.7 |

| 2019 series | |

| 2014–15 to 2017–18 (BJP Years) | 7.7 |

There were rumblings of disbelief about the new figures. All reports from the ground indicated that the hastily announced demonetisation in November 2016 and then the badly designed GST in mid-2017 had devastated the economy, especially the informal sector. But the new official estimates claimed that India had grown at a whopping 8.2 percent in 2016–17, and 7.2 percent in 2017–18 (see Chart 1.1). These figures were simply unbelievable!

Arvind Subramanian, who was the Modi Government’s Chief Economic Advisor from 2014 to 2018, let the cat out of the bag after resigning. In a working paper published in June 2019, he admitted that India’s GDP was overestimated by 2.5 percentage points per year for the post-2011 period, that is, for the five year period 2012–13 to 2016–17. Instead of the reported average growth of 6.9 percent for these five years, the GDP growth was more likely to be around 4.4 percent.[13]

There is a limit as to how much you can manipulate data. As the economic situation worsened, the CSO was forced to admit that the economy was slowing down: the GDP growth rate slowed down for 9 consecutive quarters to touch 3.1 percent for January–March 2020, and for 2019–20 as a whole, the growth rate fell to just 4 percent, an 11-year low (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3: GDP Growth Rate Before the Pandemic, 2016–17 to 2019–20

(constant prices, %) [14]

| 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

| GDP Growth Rate | 8.3 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 4 |

This means that the economy had begun sinking into recession even before the corona pandemic hit the economy.

After that, the pandemic struck. The Modi Government’s inept handling of the pandemic led to an unprecedented economic collapse. Official data admitted that the economy contracted by –23.9 percent in the first quarter of 2020–21.[15] For the full year, the CSO estimated that the economy had contracted by –8 percent (this has since been revised to –5.8 percent).[16] India witnessed perhaps the sharpest drop in GDP among the major economies of the world in 2020–21.[17]

With the lifting of the lockdown, the economy began to recover. Once again the Modi Government’s trumpeters have begun to proclaim that India’s post-pandemic growth rates are the highest among the major economies (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4: GDP Growth Rate, Post-Pandemic, 2020–21 to 2023–24 (%) [18]

| 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | 2023–24 | ||

| 1 | GDP Growth RateΩ | 7.2 | 7.3 | ||

| 2 | GDP Growth Rate† | –5.8 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 7.6 |

| 3 | GDP Growth Rate* | 7.0 | 8.2 |

ΩFirst Advanced Estimates (5 January 2024);

†Second Advanced Estimates (29 February 2024);

*Provisional Estimates (31 May 2024).

Several mainstream economists have questioned the reliability of the latest figures dished out by the CSO. For instance, in September 2023, Ashoka Mody, a professor of economics at Princeton University, wrote an article in a reputed international publication, accusing the Indian government of conducting a “branding and beautification” exercise on its GDP numbers to make them look better in the run-up to the G20 summit. The CSO had estimated an annual growth of 7.8 percent in the first quarter (April–June) of 2023–24. Mody argued that the CSO had calculated India’s GDP growth on the basis of output or production data. But there was a huge discrepancy between this figure and GDP measured on the basis of expenditure: expenditure had risen by only 1.4 percent. When the discrepancy is negligible, it can be ignored, but when the discrepancy is large, then the international best practice is to take both figures into consideration. For instance, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) of the USA uses an average of the two. If we use this methodology, then the Q1 2023–24 growth rate falls from the headline 7.8 percent to 4.5 percent.[19]

If we extend this argument to the latest provisional growth rate for 2023–24 (see Table 1.5), which is estimated by the CSO to be 8.2 percent, then since GDP growth rate based on expenditure is 3.8 percent, the average of the two figures or GDP growth rate works out to 6 percent — this is more than 2 percentage points less than GDP growth rate based on production data.

Table 1.5: GDP Based on Production data and Expenditure data,

2023–24 and 2022–23 (Rs. crore)

| 2022–23 | 2023–24 | Growth rate, % | |

| GDP (based on production) | 1,60,71,429 | 1,73,81,722 | 8.2 |

| Discrepancies

(in expenditure component) | –5,53,897 | 1,29,012 | |

| GDP (based on expenditure) | 1,66,25,326 | 1,72,52,710 | 3.8 |

More recently, the well known economist and former Chief Statistician of India Pronab Sen has pointed out another important discrepancy in the GDP data released on 29 February 2024 by the CSO (given in Row 3 in Table 1.4), which indicated that the GDP growth rate is overestimated. According to Sen, private consumption growth numbers correlate very closely with the GDP growth figure. If GDP growth is X percent, then consumption growth can at most be 0.5 to 1 percentage points less than X. This means if GDP growth is estimated to be 7.6 percent for 2023–24, then consumption growth should be at least 6.6 percent. But official data shows consumption growth to be only about 3 percent, or less than half of GDP growth. Sen argues that the only possible conclusion that can be drawn from this is that GDP growth is overestimated.[20]

The latest GDP growth rate data for 2023–24 (provisional estimates, 31 May 2024) given in Table 1.6 also shows the consumption growth to be a huge 4.2 percentage points less than GDP growth rate. Following Pronob Sen’s argument, this means that GDP growth rate for 2023–24 is overestimated, by around 3 percentage points. The arguments of both Pronob Sen and Asoka Mody point to the same conclusion.

Table 1.6: GDP and PFCE, 2022–23 and 2023–24 (Rs. crore) [21]

| 2022–23

FRE (1) | 2023–24

PE (2) | Growth rate (2 over 1), % | |

| GDP at Constant Prices | 1,60,71,429 | 1,73,81,722 | 8.2 |

| Private Final Consumption Expenditure | 93,23,825 | 96,99,214 | 4 |

FRE: First Revised Estimate; PE: Provisional Estimate

Several other economists too have questioned India’s GDP growth rates. To give just one more example: Rajeswari Sengupta, Associate Professor of Economics, IGIDR, says that under the new methodology adopted by the CSO in 2015, GDP is measured in nominal terms, which is then deflated by price indices to derive the real numbers. The deflator has therefore become crucial. She takes the example of Q3 2023–24 data released by the CSO that estimates nominal GDP growth of 10.1 percent and real growth of 8.4 percent, implying that the deflator is 1.7 percent. But how can India’s inflation be so low? Clearly, there is a problem with the deflator.[22] This argument too can be extended to the latest GDP growth rate for 2023–24, wherein the CSO has estimated nominal GDP growth rate to be 9.6 percent and real GDP growth rate to be 8.2 percent, implying a GDP deflator of just 1.4 percent — which again is absurdly low.

All the arguments given above only go to show that the Indian economy is not doing as well as the Modi Government is claiming. India’s real GDP growth rate is much below the CSO estimates.

Problem 2: Methodology Problems

The second problem with GDP data relates to the methodology used by the CSO to calculate GDP — it suffers from a serious infirmity.

The Indian economy consists of two broad sectors: the organised and the unorganised. The organised sector produces about 55 percent of the output, but employs only 6 percent of the workforce; the unorganised sector contributes to 94 percent of the employment and 45 percent of the output of the economy. Of this, agriculture contributes to around 45 percent of the workforce and 14 percent of the GDP.[23] The data for the organised sector are produced regularly every year, and so its contribution to the GDP can be accurately estimated. Of the unorganised sector, data is available only for agriculture. For the remaining unorganised sector, which has 99 percent of all production units and contributes to 31 percent of the GDP, data is collected only once in five years. In between these years, the unorganised sector’s contribution to the GDP is calculated using growth of the organised sector. The last such survey was carried out in 2015–16; after that, the Modi Government has not carried any such surveys, and also scrapped all other surveys that could have given us factual data about the state of the unorganised sector.[24]

Under normal conditions, data for the organised sector can be used to estimate the contribution of the unorganised sector to the GDP. However, with the economy suffering two shocks in quick succession — first demonetisation, and then the structurally faulty GST — this assumption was no longer valid. The unorganised sector declined sharply, while the organised sector did not. A 2018 survey by the All India Manufacturers’ Organisation, which represents over three hundred thousand units — including a large number of micro, small and medium enterprises — showed that the number of jobs in micro and small enterprises had declined by roughly a third since 2014. In medium-scale enterprises, about a quarter of jobs had been lost, and among traders the decline was over 40 percent.[25] A study by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) too noted that the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) had been adversely hit by demonetisation and GST.[26] This suggests that during the second half of 2016–17, after the implementation of demonetisation in November 2016, the growth rate of the non-agricultural unorganised sector had fallen to zero, and in 2017–18, after the implementation of GST, it had contracted by at least –10 percent, even by a conservative estimate.[27] Combining these figures with the official GDP growth rate of 8.2 percent for 2016–17 and 6.8 percent for 2017–18 — both of which represent the growth rate of the organised sector only — the actual growth rate works out to 4.2 percent for 2016–17 and an even lower 1.6 percent for 2017–18.[28] CSO data admit that the economy had slowed down to 6.5 percent in 2018–19 and 3.9 percent in 2019–20. With the Modi Government taking no steps to revive the crisis-ridden unorganised sector, the actual slowdown must have been more than these official figures.[29]

Then, in 2020, the corona epidemic hit the economy, and it suffered an unprecedented economic collapse. The CSO estimates an economic contraction of –23.9 percent during the first quarter of FY21. But again, this reflects only the decline of the organised sector. The unorganised sector suffered an even worse collapse, as it was hit hardest by the brutal lockdown. Professor Arun Kumar, a noted economist who is also Malcolm Adiseshiah Chair Professor at Institute of Social Sciences and former head of Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, JNU, estimates that the unorganised sector probably declined by around 70–80 percent during the first quarter of FY21. Incorporating this figure into GDP data, he calculates that the economy probably declined by –47 percent during April–June 2020, and not –23.9 percent. For the full financial year 2020–21, while the CSO estimates the contraction to be –7 percent, factoring in the decline suffered by the unorganised sector, Professor Arun Kumar estimates the contraction to be a whopping –29 percent.[30]

Post-pandemic, the Modi Government has been euphoric about the economy’s rate of growth being the highest among the major economies. But several data sets indicate that these figures again represent the growth rate of the organised sector only, while the unorganised sector continues to flounder:

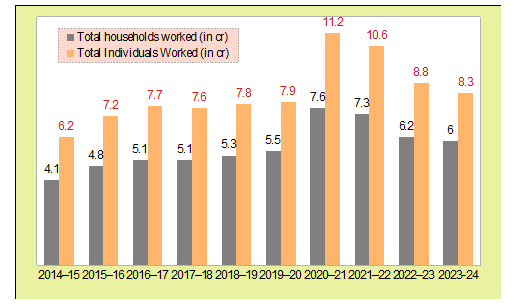

- Work demand under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) continues to be more than the pre-pandemic level. This can be seen from Chart 1.2. Even after 3 years of high (official) growth rates, the total number of individuals who worked under MGNREGA in 2023–24 (8.3 crore) is more than that in the pre-pandemic period (7.9 crore in 2019–20). This high demand for low wage MGNREGA work only means that the economic recovery has occurred primarily in sectors and activities which are not employment-intensive; while the employment intensive petty and small-scale sectors have been left out of the ambit of the recovery.[31]

Chart 1.2: Employment Provided Under MGNREGA, 2014 to 2023 (in crore) [32]

- Labour Bureau data from 2014–15 to 2021–22 shows that during these eight years, the growth rate of real wages was below 1 percent per year across the board for all three groups of workers — agricultural and non-agricultural workers, and construction workers. More recent wage data presented in the Economic Survey 2022–23 shows that this pattern of stagnation has continued till the end of 2022.[33]

- Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) data also show that real wages of casual workers and self-employed workers, who constitute more than 75 percent of the workforce, have stagnated over the period 2017–18 to 2021–22.[34]

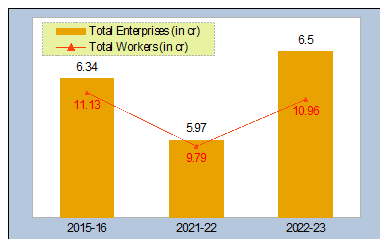

More recently, in June 2024, the government finally released reports of the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises (ASUSE) for 2021–22 and 2022–23. The unincorporated sector enterprises (USE) represent much of what we call the non-agricultural informal sector; these enterprises provide employment to about 20 percent of the total workforce in the country (10.96 crore out of 56.7 crore). The data provided by these reports, when compared with the previous ASUSE report of 2015–16, provide striking evidence of the deep crisis that has engulfed this sector following the 3 shocks of demonetisation, flawed GST and unplanned and badly managed lockdown (Chart 1.3). As per the data, during the 6-year period 2015–16 to 2021–22, the total number of units declined from 6.34 crore in 2015–16 to 5.97 crore in 2021–22 — implying that 37 lakh units had closed down over this period. And the total number of workers declined from 11.13 crore to 9.79 crore — a massive 1.34 crore workers had lost their jobs. Over the next year (2021–22 to 2022–23), while there was some recovery in this sector with the number of units increasing to more than the 2015–16 level (6.5 crore), the number of workers was still below the 2015–16 level (10.96 crore).

Chart 1.3: Unincorporated Sector Enterprises:

Number of Units and Workers Employed, 2015-16 to 2022-23 (in crore)[35]

The reason for this continuing crisis of the unorganised sector is that instead of providing some relief to the unorganised sector to help it recover, the Modi Government has used the crisis plaguing this sector to corporatise the economy.

Professor Arun Kumar estimates that the decline in the unorganised sector in 2022–23 could be between 5.6 percent and 9.3 percent; factoring in this decline into the official growth rate, the actual growth rate of the economy in 2022–23 works to be between 2.5 percent and 3.5 percent.[36]

This corroborates the argument given above, that the growth rate for the post-pandemic years is overestimated.

Problem 3: Data Deficiencies

This methodological problem in calculating the GDP is compounded by data deficiencies. Even for the organised sector, only limited data is available. For instance, the corporate sector data representing industry is available only for a few hundred firms. In the case of agriculture, it is assumed that targets set by the ministry are achieved. But that has not been the case in the last few years due to heat or late rains or inability of perishable crops to come to the market during the lockdown and demonetisation, so that it rotted in the fields and agricultural output declined while the government assumed that it has increased.[37] This probably explains why the official GDP growth rate for agriculture for 2016-17 of 6.8 percent is overestimated, as the agricultural sector was hit hard by demonetisation.

Estimating Actual GDP of the Indian Economy

We can now make a rough estimate of what is the actual GDP in 2023–24, based on the above discussion.

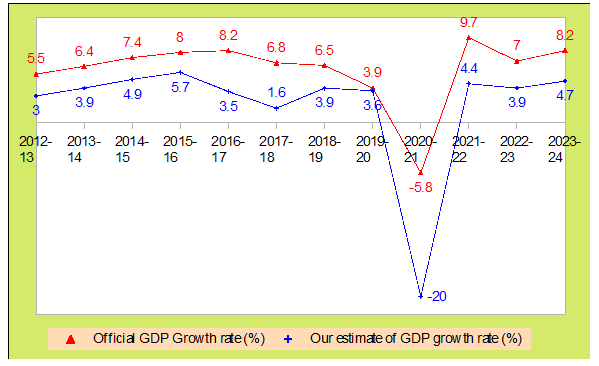

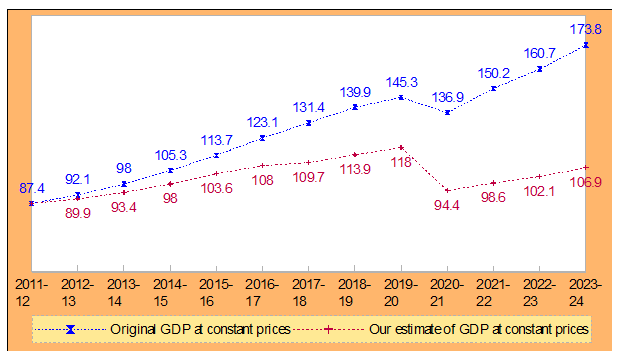

Based on the discussion above, we first plot the actual GDP growth rate at constant prices in Chart 1.4.

Chart 1.4: Official GDP Growth Rate and Our Estimates, 2012–13 to 2023–24

(at 2011–12 constant prices) (%)[38]

Based on these GDP growth rates, we then estimate the actual GDP for the years 2012–13 to 2023–24 in Chart 1.5. As can be seen from the chart, the actual GDP for 2023–24 at constant prices works out to Rs. 106.9 lakh crore, which is 61.5 percent of the official GDP figure of Rs. 173.8 lakh crore estimated by official statisticians.

Chart 1.5: Official GDP and Our Estimates, 2011–12 to 2023–24

(at 2011–12 constant prices) (Rs. lakh crore)

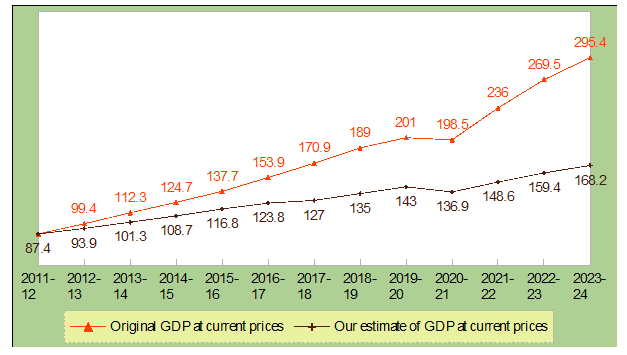

Assuming that the ratio of GDP at current prices to constant prices remains the same as in official data, we can now calculate the actual GDP at current prices. This is done in Chart 1.6. We estimate the actual GDP at current prices to be Rs. 168.2 lakh crore for 2023–24, which is 56.9 percent of the official GDP of Rs. 295.4 lakh crore! We are not even a $2 trillion economy.

Chart 1.6: Official GDP and Our Estimates, 2011–12 to 2023–24

(at 2011–12 current prices) (Rs. lakh crore)

Notes

- Economic Survey 2023–24, p. vii.

- “India to be $5 Trillion Economy by 2027–28: Finance Minister”, 11 January 2024, https://www.deccanherald.com.

- Indian Economy – A Review, Department of Economic Affairs, Government of India, p. 64.

- Viksit Bharat, https://www.niti.gov.in

- Economic Survey 2023–24, p. 155.

- M.G. Devasahayam, “India’s ‘Amrit Kaal’: Hunger, Inequity and a $30-Trillion Economy”, 2 December 2023, https://thewire.in.; “Nothing Can Stop India from Becoming $35 Trillion Economy, Says Mukesh Ambani”, 10 January 2024, https://www.indiatoday.in.

- “India’s Income Inequality Is Now Worse Than Under British Rule, New Report Says”, 27 March 2024, https://time.com.

- Amitabha Roychowdhury, “Multilateral Banks Debunk Govt Claims on India’s Growth Rate”, 9 May 2023, https://www.newsclick.in; Arun Kumar, “The Hollowness of the Modi Government’s Tall Claims and Self-Praise on Economy”, 18 August 2023, https://thewire.in.

- Peter. S. Goodman, “Emphasis on Growth Is Called Misguided”, 22 September 2009, http://www.nytimes.com; Vandana Shiva, “How Economic Growth has Become Anti-Life”, 1 November 2013, http://www.theguardian.com; David Jolly, “G.D.P. Seen as Inadequate Measure of Economic Health”, 14 September 2009, http://www.nytimes.com. See also our booklet: “Is the Government Really Poor?”, Lokayat publication, 2018, available online at https://lokayat.org.in.

- For more on this, see: Jayati Ghosh, “Hindutva, Economic Neoliberalism and the Abuse of Economic Statistics in India”, South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 2020, https://journals.openedition.org.

- Rajesh Kumar Singh, Manoj Kumar, “Methodology Change Sees Indian Economy Grow Faster than China’s”, 9 February 2015, https://in.reuters.com. “India Fastest Growing Economy”, 9 February 2015, https://www.thehindu.com. For the two sets of figures, see: Advance Estimates of National Income, 2014-15, 9 February 2015, https://pib.gov.in; and: Advance Estimates of National Income, 2015-16, 8 February 2016, https://pib.gov.in.

- For July 2018 figures: “Simply Put: This Back Series, That Back Series”, 30 November 2018, https://indianexpress.com; For November 2018 figures: Press Note on National Accounts Statistics Back-Series (2004–05 to 2011–12), 28 November 2018, http://www.mospi.gov.in; For 2019 figures: Press Note on First Revised Estimates of National Income, Consumption Expenditure, Saving And Capital Formation for 2017–18, 31 January 2019, http://www.mospi.gov.in. We have discussed this manipulation in detail in a previous article in Janata Weekly: Neeraj Jain, “Modinomics = Falsonomics: Part I”, Janata Weekly, 31 March 2019, https://janataweekly.org.

- Subramanian based his calculations on the July 2018 back series of the NSC committee. Arvind Subramanian, “India’s GDP Mis-estimation: Likelihood, Magnitudes, Mechanisms, and Implications”, CID Faculty Working Paper No. 354, June 2019, https://www.hks.harvard.edu.

- Press Note on First Revised Estimates of National Income, Consumption Expenditure, Saving and Capital Formation for 2019–20, 29 January 2021, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

- Press Note on Estimates of Gross Domestic Product for the First Quarter (April-June) 2020-2021, 31 August 2020, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

- Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2020–21 …, 26 February 2021, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

- Prabhat Patnaik, “The Current State of India’s Economy”, 24 April 2023, https://www.networkideas.org.

- GDP data in Row 1 from: Press Note on First Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24, 5 January 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in; Row 2 from: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, 29 February 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in; Row 3 from: Press Note on Provisional Estimates of Annual GDP for 2023–24 and Quarterly Estimates of GDP for Q4 of 2023–24, 31 May 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

- Ashoka Mody, “India’s Fake Growth Story”, 6 September 2023, https://www.project-syndicate.org. See also: “The Rising Discrepancies in Indian GDP Data Point to a False Growth Story, Say Experts”, The Wire Staff, 7 September 2023, https://thewire.in.

- M.K. Venu, “Sluggish Consumption Data Debunks PM Modi’s High GDP Growth Claims”, 5 March 2024, https://thewire.in.

- Press Note on Provisional Estimates of Annual GDP for 2023–24 …, op. cit.

- Rajeswari Sengupta, “Is India’s Growth Rate Overestimated?”, 29 March 2024, https://indianexpress.com. See also: Vivek Kaul, “Finally, an Economist Explains Why the Indian GDP Growth Number Is Wrong”, 19 March 2016, https://vivekkaul.com.

- Arun Kumar, Digitalisation’s Marginalising Impact on India’s Unorganised Sector, 7 April 2024, https://rupe-india.org. According to Pronab Sen, economist and famed statistician who oversaw the 2011–12 re-basing of GDP as chairman of the National Statistical Commission (NSC), during the 2011–12 re-basing of the GDP series, the contribution of the unorganised sector was taken to be 47 percent. Cited in: Prasanna Mohanty, “Recession Reality Check: Do Quarterly GDP, Other Indicators Reflect the True State of Economy?”, 9 December 2019, https://www.businesstoday.in.

- Arun Kumar, “The Gathering Storm”, 4 November 2019, https://caravanmagazine.in; Prasanna Mohanty, ibid.; Arun Kumar, “What Do We Really Know About India’s GDP?”, 4 January 2024, https://thewire.in.

- Arun Kumar, “Falling Fortunes”, 30 January 2019, https://caravanmagazine.in.

- “MSME Worst Hit by GST, Demonetisation, Says RBI Study”, 18 August 2018, https://www.business-standard.com.

- This estimate of the unorganised sector having contracted by –10 percent is given in: Arun Kumar, “Falling Fortunes”, op. cit.

- Our estimates. For 2016–17: we base ourselves on the growth rate calculated by Arvind Subramanian, and factor in the collapse of the non-agricultural unorganised sector for the second half of the year (Arvind Subramanian estimates GDP growth rate to be 4.6 percent; so we assume that growth rate of non-agricultural unorganised sector is 2.3 percent for the full year). For agriculture, we take the latest official agricultural growth rate of 6.8 percent, even though this seems to be an overestimate.[Agricultural growth figures taken from: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, 29 February 2024, op. cit.] For 2017–18, we have recalculated the GDP growth rate estimated by Arun Kumar (he estimates it to be 1 percent), taking into account the latest GDP and agricultural growth rate figures, as given in Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, ibid.

- For more on the impact of GST on unorganised sector, see: Arun Kumar, Digitalisation’s Marginalising Impact on India’s Unorganised Sector, op. cit.

- Arun Kumar, “What the 23.9% Drop in Q1 GDP Tells – and Doesn’t Tell – Us About the Economy”, 2 September 2020, https://thewire.in; “State of Economy Far Worse Than Govt Admits, GDP Shrank by More Than What Govt Claims”, Arun Kumar interviewed by Karan Thapar, 30 January 2021, https://thewire.in.

- “Rise in Demand for MGNREGS a ‘Living Monument’ of Govt. Failure, Says Jairam Ramesh”, 1 April 2024, https://www.thehindu.com.

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme, Scheme at a Glance, https://nrega.nic.in, accessed on 10 July 2024.

- Jean Dreze, “Wages are the Worry, Not Just Unemployment”, 13 April 2023, https://indianexpress.com. See also: C.P. Chandrasekhar, “GDP Estimates Fail to Adequately Capture Informal Sector”, 15 June 2023, https://frontline.thehindu.com.

- State of Working India 2023, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, https://publications.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in. This data is discussed in greater detail in the next chapter on unemployment.

- Dipa Sinha, “The Latest ASUSE Reports Show How Deep in Trouble the Informal Sector Is”, 16 July 2024, https://thewire.in.

- Arun Kumar, “Three Notes of Caution as India Celebrates Its GDP Growth”, 2 June 2023, https://thewire.in.

- Arun Kumar, “What Do We Really Know About India’s GDP?”, op. cit.

- For official GDP data, we have taken the latest GDP figures, as given in: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, 29 February 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in. For 2023-24, GDP data taken from: Press Note on Provisional Estimates of Annual GDP for 2023–24 and Quarterly Estimates of GDP for Q4 of 2023–24, 31 May 2024, https://www.mospi.gov.in.

For making our estimates of actual GDP growth, we have taken Arvind Subramanian’s estimates of GDP growth rate till 2015–16. For the subsequent years, we take the official GDP growth rate data to be growth rate data for the organised sector, and for the non-agriculture unorganised sector we take the growth rates based on the discussion in this chapter. For agriculture, we have used the latest agricultural growth rate figures, even though they appear to be overestimated, as given in: Press Note on Second Advance Estimates of National Income 2023–24 …, 29 February 2024, op. cit. For calculating the GDP growth rates, we combine these three using the methodology suggested by Prof Arun Kumar in his article: Arun Kumar, “Falling Fortunes”, 30 January 2019, https://caravanmagazine.in. For 2020–21, we have taken a more liberal estimate of the collapse rather than the –29 percent estimated by Prof Arun Kumar. For the post-pandemic years, we have taken a more liberal estimate of the decline in the unorganised sector, as compared to the estimate by Prof Arun Kumar cited in this chapter.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)