(Note: Most readers will have seen this article. We had posted it earlier on our mailing list. We are printing it here to formally include it in the magazine.)

The Economic Survey 2023–24 claims: “Growth has been inclusive with a reduction in unemployment … and an increase in labour force participation.”[1] In support of this, it gives data from the PLFS surveys[2] conducted from 2017–18 to 2022–23 (all data are based on usual status, age 15 years and above):

- the unemployment rate (UR) has declined substantially from 6 percent in 2017–18 to 3.2 percent in 2022–23 [UR is the percentage of labour force that is unemployed];

- the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) has increased from 49.8 percent in 2017–18 to 57.9 percent in 2022–23 [LFPR is the percentage of working-age population engaged in work or making tangible efforts to seek ‘work’.];

- the Worker Participation Rate (WPR) has increased from 46.8 percent in 2017–18 to 56 percent in 2022–23 [WPR, also called the employment rate, is the total number of people employed as a percentage of the working age population];

- youth (age 15–29 years) Unemployment Rate has declined from 17.8 percent in 2017–18 to 10 percent in 2022–23, while youth LFPR has increased from 38.2 percent to 44.5 percent over the same period;

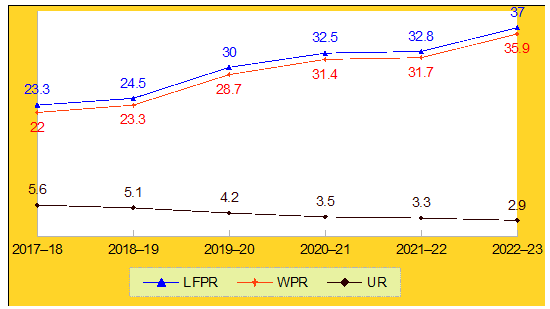

- the Female Labour Force Participation Rate (FLFPR) has risen from 23.3 percent in 2017–18 to 37 percent in 2022–23.[3]

The Economic Survey 2023–24 also says that “India’s workforce is estimated to be nearly 56.5 crore in 2022–23 using WPR from PLFS and MoHFW’s population projections.”[4] Using this data, the total unemployed for 2022–23 works out to a very low 2.02 crore (in usual status).[5]

More recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi came up with an even more astonishing claim, that India created “eight crore new jobs in the last three to four years”. The Prime Minister was using data from the India–KLEMS database hosted by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). On the basis of this database, RBI has estimated employment data at an all-India level. The RBI report does a Houdini act of not just making joblessness vanish, it posits an employment explosion! As per the RBI, total number of jobs in the country increased from 47.5 crore in 2017–18 to 56.6 crore in 2020–21 and 64.3 crore in 2023–24. Thus, according to the RBI, India added 16.8 crore jobs in the six years since 2017–18.[6] This works out to an average of 2.8 crore jobs a year! It means that one-fourth of the total jobs in the economy have been created in just the past six years. This job generation took place even during the pandemic years!

This employment data cited by PM Modi is simply too absurd for us to comment. Actually, the objective of the KLEMS database is not to produce employment data; it is a framework used to measure industry-level ‘total factor productivity’ (TFP). The employment figures are merely inputs into the database’s modelling framework; the RBI sources this data from official sources such as the PLFS and CSO. Commenting on the use of this database as source for employment data, P.C. Mohanan and R. Ramakumar, both well-known economists, write: “It is amusing then that data sourced by the RBI from other official sources, and used as inputs to estimate TFP, are portrayed as ‘RBI jobs data’ to make political statements on employment generation in the economy.”[7]

The point we are trying to make is: the Modi Government is in denial about the country’s unemployment crisis; according to it, the economy is generating sufficient number of jobs. The Finance Minister’s budget speech does not even mention the word ‘unemployment’. Nevertheless, her budget speech says that “in this budget, we particularly focus on employment”. She unveils a “Prime Minister’s package of 5 schemes and initiatives to facilitate employment, skilling and other opportunities for 4.1 crore youth over a 5-year period with a central outlay of Rs. 2 lakh crore.” But if the country is facing no unemployment crisis, the unemployment rate has declined to a historic low of 3.2 percent, and there are just around 2 crore unemployed in the country, then what is the need for announcing a Rs. 2 lakh crore package to generate 4.1 crore jobs?

We discuss the ‘Prime Minister’s Package for Employment and Skilling’ in a subsequent chapter. In this chapter, we investigate the unemployment data given in the Economic Survey 2023–24, that is based on PLFS data released by the National Statistical Office (NSO).

PLFS collects data in two ways — usual status (US) and current weekly status (CWS). Under usual status, the survey respondent has to recall their employment details from the last one year — if the person has been engaged in an economic activity for at least 30 days in the previous year, they are considered to be employed. In CWS, the respondent has to recall the details over the past one week — an individual is counted as being employed if they have worked for at least one hour on at least one day during the seven days preceding the date of survey. While both the definitions have their limitations, the data based on CWS are considered to be more reliable because the recall is better over the past week. However, the above figures given by the Economic Survey are based on usual status, probably because the usual status unemployment rate is lower than the CWS unemployment rate.

The biggest problem with PLFS data is its reliability. The Modi Government’s frequent interference in the country’s statistical system, frequent changes in methodology of the surveys, suppression and delay in release of data — all have put the credibility of NSO data under a cloud. Here is a brief history of the Modi Government’s interference in the country’s unemployment statistics.

During the first term of the Modi Government, in September 2016, data from the fifth round of the Annual Employment–Unemployment Survey (EUS) was released. This report showed that unemployment rate in India had gone up to a five-year high of 5 percent in 2015–16. The government panicked, and not only scrapped all subsequent Annual EU Surveys, but also the quinquennial Employment–Unemployment Survey conducted by the NSSO[8] — whose next round was due in 2016–17. This survey on employment and unemployment had been conducted regularly every five years since 1972–73 in rural and urban areas, and provided extensive information about the volume and structure of employment and unemployment in the country, and also several other indicators related to the quality of workers and non-workers.

Consequent to the scrapping of these surveys, the government released no official data on the unemployment situation in the country for the next three years. After much uproar by academics and economists, finally, in 2017, it instituted another employment survey, the PLFS, to be done by the NSSO. This survey was conducted between July 2017 and June 2018. But with Lok Sabha elections coming, the Modi Government decided to withhold the release of this data too. It did so despite the National Statistical Commission (NSC) — the apex body that coordinates India’s statistical activities — approving its release. The NSC is an autonomous body; the government is not supposed to interfere in its functioning. In protest, on 28 January 2019, the last two independent members of the NSC, one of whom was also the acting chairman, resigned.[9]

Finally, after the 2019 Lok Sabha elections were done and dusted with, the government released the suppressed PLFS data. It showed that joblessness was at a 45-year high of 6.1 percent in 2017–18 (the Centre has been collecting unemployment data since the early 1970s). Worse, the data showed that the total number of jobs in the economy had actually fallen in the past six years — from 47.42 crore in 2011–12 to 46.51 crore in 2017–18 (Table 2.1). It is the first time this has happened since independence.

Table 2.1: Total Employment, 2011–12 to 2017–18 (in crore) [10]

| Total Employment | |

| 2011–12 | 47.4 |

| 2017–18 | 46.5 |

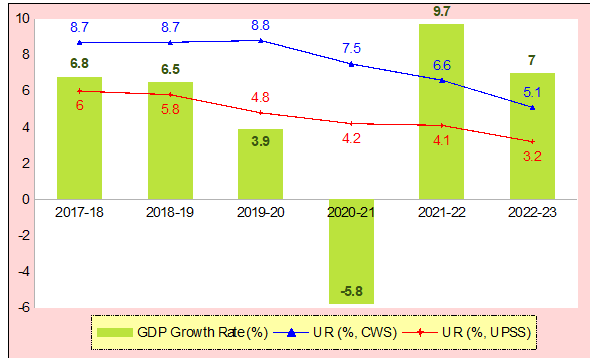

In all probability, the Modi Government now tweaked the data collection methodology. This suspicion arises because even though the country’s GDP growth rate slowed down during the years 2017–18 to 2020–21, data put out by subsequent PLFS surveys show a secular increase in the LFPR and WPR, and a decline in the unemployment rate (UR) to a lowly 3.2 percent in 2022–23 (Table 2.2)! For better visualisation, we present the data in Table 2.2 in graphic format in Chart 2.1.

Table 2.2: LFPR, WPR and UR for Persons of Age 15 Years and Above (in %) [11]

| Usual Status | Current Weekly Status | GDP Growth Rate (%) | |||||||

| WPR | LFPR | UR | WPR | LFPR | UR | ||||

| 2017–18 | 46.8 | 49.8 | 6.0 | 44.1 | 48.4 | 8.7 | 6.8 | ||

| 2018–19 | 47.3 | 50.2 | 5.8 | 44.3 | 48.5 | 8.7 | 6.5 | ||

| 2019–20 | 50.9 | 53.5 | 4.8 | 46.7 | 51.2 | 8.8 | 3.9 | ||

| 2020–21 | 52.6 | 54.9 | 4.2 | 47.9 | 51.8 | 7.5 | –5.8 | ||

| 2021–22 | 52.9 | 55.2 | 4.1 | 48.3 | 51.7 | 6.6 | 9.7 | ||

| 2022–23 | 56.0 | 57.9 | 3.2 | 51.8 | 54.6 | 5.1 | 7.0 | ||

Chart 2.1: Unemployment Rate (usual status and CWS) vs GDP Growth Rate (in %)

PLFS data also show that both LFPR and WPR have been increasing — which means that this decrease in unemployment rate has not occurred because of an increase in discouraged workers (who drop out of the labour force because they cannot find work), but because the economy has been creating more jobs. So, the PLFS data imply that despite the economy sinking into recession, employment generation is robust!

What is even more incredulous is that PLFS data show a decline in unemployment rate (on both usual status and CWS) even during the pandemic year 2020–21, a year when official figures admit that the economy contracted by –5.8 percent (see Chart 2.1), and Professor Arun Kumar estimates that the contraction was –29 percent due to the total collapse of the informal sector (as discussed in the Chapter 1). This implies that the economy created more jobs during the pandemic year 2020–21 as compared to the pre-pandemic years! In their enthusiastic massaging of survey data, the government’s spin doctors probably forgot that the data must show at least some increase in unemployment during the pandemic year for the data to have some credibility.

Several facts from the ground belie this data being dished out by the official statisticians of the Modi Government:

- In June 2022, about 17 lakh people applied for 3,400 jobs requiring a minimum qualification of Class 10 in the ‘developed’ State of Gujarat.[12]

- In end-2022, the Maharashtra police received more than 11 lakh applications for 18,300 posts of constables and drivers. In mid-2023, the State received more than 11.5 lakh applications for 4,600 posts of Talathi, a Group C post.[13]

- And in UP, the Staff Selection Commission’s (SSC) MTS 2023 recruitment examination for Group D jobs (peon, watchman, gardener, etc.) saw a staggering 55 lakh people apply for 11,400 jobs. This is more than double the number of applications received for the previous exam in 2022 — another clear indicator of the worsening employment situation. While the minimum educational requirement was only a high school diploma, candidates with much higher qualifications, such as BTech, MTech, BBA, MBA and MSc degrees applied for these jobs.[14]

The severity of the unemployment situation in the country is also revealed by a reply given in Parliament on 27 July 2022 by Dr Jitendra Singh, the Minister of State in the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions. The minister stated that between 2014 and 2022, a staggering 22.06 crore applications for jobs were received by the Central government, of which 7.22 lakh persons were recruited. According to data provided by the minister, in 2020–21, 1.8 crore persons applied for jobs with the Central government, while 78,000 recruitments were made, and in 2021–22, 1.87 crore applications were received and 38,000 recruitments made.[15] Yet PLFS unemployment data (as per usual status) show that only 2.07 crore people were unemployed in 2022–23!

It is indubitable: the country’s official statisticians have indulged in statistical jugglery to paint a rosy picture of the employment situation. This is also borne out by unemployment data from the CMIE, a reputed dataset that is increasingly being relied upon by economists and policy researchers because of the suppression of key economic data by the Modi Government.

CMIE Data on Unemployment

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) is a leading private business information company that conducts Consumer Pyramids Household Surveys (CPHS) to assess short-term changes in the economic conditions of households in India. Data from CPHS have also been used to estimate the employment–unemployment situation in the country. The government has been trying to discredit the CMIE data, claiming that the surveys of such private organisations are “generally neither scientific nor based on internationally accepted norms”.[16] While the CMIE data has some limitations, it also has several merits, such as: it uses internationally compliant definitions, which PLFS does not (PLFS regards unpaid family labour as employment, which CMIE does not — more on this below); the CMIE sample is actually larger than that of PLFS; and it covers both the organised and unorganised sectors, and both rural and urban areas.[17] But the bigger problem, because of which researchers are forced to use CMIE data, is the decline in the quality of data being provided by India’s official statistical agencies.[18]

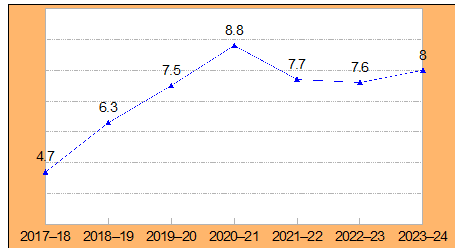

We give the unemployment rate in the country as estimated by CMIE in Chart 2.2 .

Chart 2.2: CMIE Unemployment Rate for Persons of Age 15 Years and Above,

2017–18 to 2023–24 (in %)[19]

These unemployment figures are clearly closer to reality. The CMIE unemployment rate (UR) which was 4.7 percent in 2017–18, rose to 7.5 percent in 2019–20. It shot up to 8.8 percent in 2020–21, the year the country was hit by the pandemic. The post-pandemic marginal recovery (as discussed in the previous chapter) led to a slight decline in the UR till 2022–23, but it has again increased to 8 percent in 2023–24, which is higher than the UR of 7.5 percent in 2019–20! And the latest monthly data from the CMIE show that the unemployment rate has climbed to 9.2 percent in June 2024![20]

This means that the recovery has occurred primarily in sectors and activities which are not employment-intensive; implying that the employment intensive petty and small-scale sectors have been left out of the ambit of the recovery. This is precisely what we have pointed out the previous chapter, where we have discussed the problems with the country’s high post-pandemic GDP growth rate data.

Estimating the Actual Unemployment Rate in India

Good data or bad, data always reveals a lot. A deep dive into PLFS data reveals several problems with the data collection methodology of PLFS, because of which the employment data derived from it becomes so ludicrous.

i) The Category of Unpaid Workers

One major problem with PLFS data is that its data collection methodology regards unpaid family labour as employment. In PLFS data, within the category of self-employment, there is a special category called “unpaid helper in family enterprises”. India is perhaps the only country in the world that includes such workers in employment data. As per the definition of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), which is followed by all countries of the world but not India, employment covers only that part of work which is remunerated. Therefore, unpaid work of any kind, whether in the family enterprise or within households in care and other activities, is considered to be work but NOT employment. Yet in India, official data include this category in the workforce.[21] (The CMIE data also does not include such workers in the category of employed.)

We rework PLFS data on the basis of internationally accepted norms, and calculate the unemployment rates after excluding “unpaid workers” from the category of employed. For this, we first disaggregate the PLFS data for the period 2017–18 to 2022–23 by type of employment: self-employment, regular paid or salaried work, and casual labour. This is done in Table 2.3 for all workers of all ages (in usual status) [Note that this data is for all ages, while data in Table 2.2 is for all workers above 15 years]. For comparison, we also give data for 2017–18 and 2022–23 based on CWS.

Table 2.3: Percentage Distribution of Workers by Status in Employment [22]

(All ages, according to usual status and CWS)

| Usual Status | ||||||

| Self-employed | Regular wage | Casual labour | Total | |||

| Own-account | Unpaid Helper | Total | ||||

| 2017–18 | 38.6 | 13.6 | 52.2 | 22.8 | 24.9 | 100 |

| 2018–19 | 38.8 | 13.3 | 52.1 | 23.8 | 24.1 | 100 |

| 2019–20 | 37.6 | 15.9 | 53.5 | 22.9 | 23.6 | 100 |

| 2020–21 | 38.2 | 17.3 | 55.6 | 21.1 | 23.3 | 100 |

| 2021–22 | 38.3 | 17.5 | 55.8 | 21.5 | 22.7 | 100 |

| 2022–23 | 39 | 18.3 | 57.3 | 20.9 | 21.8 | 100 |

| CWS | ||||||

| 2017–18 | 38.4 | 12.1 | 51.9 | 24.1 | 24 | 100 |

| 2022–23 | 39.9 | 15.6 | 56.6 | 22.3 | 21.2 | 100 |

As we can see in Table 2.3, the unpaid self-employed according to usual status have increased from 13.6 percent of all workers to 18.3 percent over the six-year period 2017–18 to 2022–23. As per CWS, the unpaid self-employed increased from 12.1 percent to 15.6 percent over this period.

This increase in unpaid workers working in family enterprises only reflects an inability to find paid jobs. It confirms our analysis made in Chapter 1 that the post-pandemic economic recovery only reflects recovery in the organised sector, the unorganised sector continues to be in crisis.

As per the internationally accepted ILO definition, all these unpaid workers should be included in the unemployed, and not in the employed. We re-calculate the WPR and UR in Table 2.4, after excluding the unpaid workers from the category of employed and including them in the unemployed. (Note that the official PLFS data for WPR and LFPR in Table 2.4 is different from that in Table 2.2, as the indicators in Table 2.4 are for persons of all ages, while data in Table 2.2 is for all workers above 15 years.)

Table 2.4 shows that after excluding the unpaid workers from the category for employed, the WPR in usual status for 2022–23 drastically falls to just 33.6 percent from the earlier 41.1 percent. As per CWS, it declines from 38 percent to 32.1 percent. This is only to be expected, as the WPR had got inflated due to the addition of unpaid workers in it.

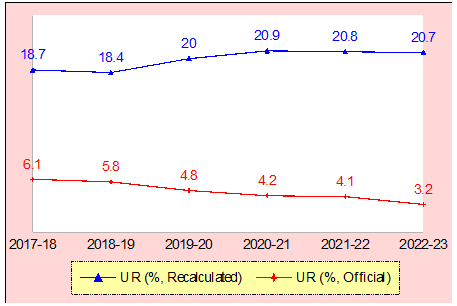

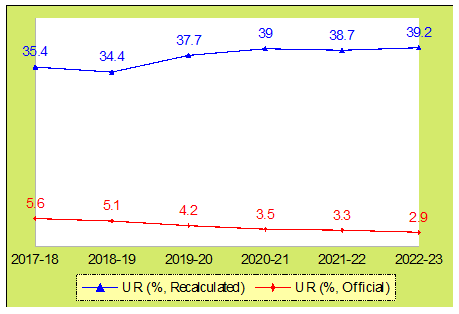

The recalculated unemployment rate for 2022–23 now shoots up to 20.7 percent for persons of all ages as per usual status. This is six times the official PLFS unemployment rate of 3.2 percent. On CWS basis, the recalculated unemployment rate for 2022–23 goes up to 19.8 percent from the PLFS rate of 5.1 percent. We present the official and recalculated unemployment rates (as per usual status) in graphic format in Chart 2.3. The data in this chart is now according to economic common sense — the reworked unemployment rate increased from 18.7 percent in 2017–18 to 20.9 percent in 2020–21, as it should because the economy slowed down during this period.

Table 2.4: Recalculated WPR and UR for Persons of All Ages

(according to usual status and CWS, in %) [23]

| Usual Status | |||||

| Official WPR | Recalculated WPR | Official LFPR | Official UR | Recalculated UR | |

| 2017–18 | 34.7 | 30 | 36.9 | 6.1 | 18.7 |

| 2018–19 | 35.3 | 30.6 | 37.5 | 5.8 | 18.4 |

| 2019–20 | 38.2 | 32.1 | 40.1 | 4.8 | 20 |

| 2020–21 | 39.8 | 32.9 | 41.6 | 4.2 | 20.9 |

| 2021–22 | 39.6 | 32.7 | 41.3 | 4.1 | 20.8 |

| 2022–23 | 41.1 | 33.6 | 42.4 | 3.2 | 20.7 |

| CWS | |||||

| 2022–23 | 38 | 32.1 | 40 | 5.1 | 19.8 |

Chart 2.3: Unemployment Rate: Official and Recalculated (usual status, %)

From the data in Table 2.4, we can calculate that the total unemployed in the country in 2022–23 is not 2.02 crore (in usual status) as claimed by the Modi Government, but 12.2 crore.[24]

ii) The Underemployed Workers

The reworked data in Table 2.4 shows that unemployment rate for all workers only marginally increased during the pandemic year 2020–21, by just 0.9 percentage points. However, all ground reports suggest that the unorganised sector suffered a terrible collapse during the lockdown, probably by as much as 70–80 percent during Q1 2020–21.[25] Subsequently, after the lockdown was gradually lifted, the unorganised sector struggled to recover due to the government’s callous handling of the lockdown.[26] The unorganised sector accounts for 94 percent of the total employment — its sharp decline must have led to crores of people losing their livelihoods. Then why has unemployment for FY21 increased by only 0.9 percentage points, even in the reworked data?

In Table 2.5, we have calculated the percentage distribution of all workers by status of employment, after shifting the category of unpaid self-employed workers to unemployed. As can be seen from the table, nearly 50 percent of all workers are self-employed, and their percentage has increased over the period 2017–18 to 2022–23 by 3 percentage points. And casual workers account for a quarter of all workers.

Table 2.5: Percentage Distribution of Workers by Status in Employment

after Excluding Unpaid Workers (in usual status)

| Self-employed, Own-account | Regular wage | Casual labour | Total | |

| 2017–18 | 44.7 | 26.4 | 28.9 | 100 |

| 2018–19 | 44.8 | 27.5 | 27.8 | 100 |

| 2019–20 | 44.7 | 27.2 | 28.1 | 100 |

| 2020–21 | 46.2 | 25.5 | 28.2 | 100 |

| 2021–22 | 46.4 | 26.1 | 27.5 | 100 |

| 2022–23 | 47.7 | 25.6 | 26.7 | 100 |

A closer examination of the data in Table 2.5 reveals another important problem with the PLFS data collection methodology, because of which its data does not reflect the huge increase in unemployment during the pandemic year 2020–21.

The overwhelming majority of the casual workers work in insecure low-paid jobs with no social security, like in the construction sector or in roadside eateries or in tiny enterprises. PLFS data give the average earnings of casual workers. Table 2.6 gives the real earnings of workers, after making adjustments for inflation using CPI. The data shows that real wages of casual workers have increased by a mere 2.6 percent over the period 2017–18 to 2022–23. Even after this increase, the real wages in 2022–23 were only Rs. 7,899. The India Employment Report 2024 of the ILO gives the distribution of casual workers by monthly wages on the basis of PLFS data and estimates that 78 percent of the casual workers earn less than Rs. 7,500 per month.[27] How do people survive on a daily wage of Rs. 250!

Table 2.6: Average Real Monthly Wage / Salary Earnings of Workers

Estimated from PLFS Various Rounds (according to CWS, in Rs.) [28]

| 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 | |

| Self-employment | 12,318 | 12,988 | 11,560 | 11,411 | 12,089 | 13,347 |

| Casual wage | 6,959 | 7,209 | 7,324 | 7,431 | 7,856 | 7,899 |

| Regular wage | 19,450 | 19,690 | 18,907 | 19,074 | 19,456 | 20,039 |

As regards the self-employed workers, in most cases, self-employment reflects the absence of not just good quality paid employment, but any kind of paid employment. People selling idlis or pani-puris by the roadside, people selling fruits and vegetables on handcarts from 7 am to 9 pm, rickshaw pullers and auto-rickshaw drivers — most of these self-employed people do these low-paying jobs because of the absence of any kind of paid employment. None of these jobs have any kind of social security, nor any accident insurance, they often have to pay bribes to the local police, etc. Many do not even get free rations under the National Food Security Act. PLFS data on earnings of self-employed workers (Table 2.6) show that real wages for these workers had started declining even before the Covid-19 pandemic. They further fell during the pandemic. The post-pandemic recovery led to some rise in wages, but the increase has been so anaemic that average real wages in 2021–22 were below 2017–18. It is only in 2022–23 that they crossed the pre-pandemic levels.

Despite falling real wages, the percentage of people in self-employment increased over the period 2017–18 to 2021–22. Why? Because there are no jobs.

In 1973–74, India’s Planning Commission defined the poverty line as that particular level of total spending per capita on all goods and services, whose food spending part satisfied the nutrition level of 2,200 calories of energy intake per day in rural India, and 2,100 calories per day in urban areas. It applied this definition to NSS data for 1973–74, and estimated the poverty line to be Rs. 49/56 per day for rural/urban families. Since then, all kinds of subterfuges have been adopted by all subsequent governments at the Centre to change this definition and show a decline in poverty. But if we stick to this sensible definition of the poverty line, and use the NSSO data for 2017–18 to estimate the per capita expenditure level at which exactly 2,200 calories were accessed in rural India, then that works out to Rs. 70 in 2017–18, or Rs. 8,400 for a family of four. Updating it to 2022–23 (using the Agricultural Labourers Price Index), the poverty line works out to Rs. 10,853 per month.[29]

A comparison of this poverty line with the average wage of casual workers as given in Table 2.6 reveals the astounding fact that the average wage of casual workers in 2022–23 is 30 percent less than this poverty line. [This poverty line is for a family of four. But since more than 80 percent of the female workforce in India is not engaged in any paid economic activity (see below), we can take the data in Table 2.6 to represent household income too for most families.] This means that the overwhelming majority of casual workers are living in penury. And the average wage of the self-employed workers is just 22 percent above this poverty line, which means the majority of self-employed workers must also be living on the edges of destitution.

Nearly 50 percent of the workforce earns barely enough to eke out a living. Why do people work in such low-paying insecure jobs? Because there is no unemployment allowance in the country. So people have the option of either starving, or taking up whatever jobs are available, doing any kind of work, to somehow earn something and stay alive.

All unemployment surveys in India, be it the NSSO surveys or the CMIE surveys, consider all these workers in the informal sector to be ‘gainfully employed’, even if they are earning subsistence level wages. The reason why the PLFS data shows such a marginal increase in unemployment in 2020–21 is because people were trying to do something or the other to somehow stay alive — they had no option, as the relief package given by the government was meagre. By PLFS definition, all these people are included in the “employed” category.

Defining all such people as “employed” is actually ridiculous; they are all victims of an economy that is unable to create decent jobs. Any humane society would consider them to be unemployed, or at least under-employed. International covenants such as ‘The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’, and our own Constitution explicitly state that all workers have the right to a decent job that ensures them and their families a life of dignity. In 2015, the United Nations passed a landmark resolution announcing seventeen Sustainable Development Goals. One of these goals was providing “decent work for all”. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) in fact says that only those who are doing “decent” jobs should be considered as employed. The ILO defines “decent work” as work that delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for all, freedom for people to express their concerns (in plainer language, this means workers must have right to form trade unions and engage in collective bargaining), and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.[30] This means that all workers whose earnings are able to provide them only the bare necessities of life should be recognised as ‘under-employed’, and included in the unemployed.

If we include all these underemployed workers in the total number of unemployed in the country, the unemployment rate would go from the 20 percent estimated above to at least 50 percent, if not more! The total number of unemployed and underemployed would zoom to more than 29 crore. Terrible figures indeed.

But as we see below, even these mind-boggling unemployment figures are an underestimate!

iii) Discouraged Workers

A third problem with PLFS data becomes evident if we examine the Labour Force Participation Rate. It reveals that despite the inclusion of so many unpaid workers, the LFPR in India for persons aged 15 years and above is only 54.6 percent as per CWS and slightly higher at 57.9 percent in usual status (in 2022–23; see Table 2.2).

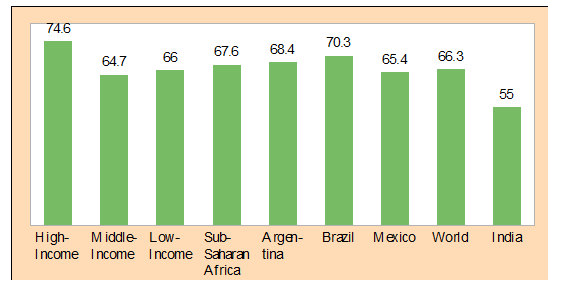

This figure is significantly less than that for other countries. The LFPR for high-income countries is 74.6 percent, nearly 20 percentage points more; for middle-income countries, it is 64.7 percent; for low-income countries, it is 66 percent; even for poverty-stricken sub-Saharan Africa, it is 67.6 percent. For other emerging market countries whom India considers as its peers, the LFPR is 68.4 percent for Argentina, 70.3 percent for Brazil and 65.4 percent for Mexico. The world average is 66.3 percent (see Chart 2.4).

Chart 2.4: Labour Force Participation Rate, India vs Other countries, 2022–23 (in %) [31]

The reason why India’s LFPR is so low is because of the country’s appalling unemployment crisis, which has only been getting worse during the Modi years. There are simply no jobs. Consequently, many workers have simply given up looking for jobs — out of frustration, because they have not been able to find a job for a long time. In official parlance, they are known as “discouraged workers”; such workers are not included in the official figures of the unemployed, nor are they included in the labour force.

But actually they should be included in both, as they have not dropped out of the labour force willingly, but due to frustration! Any pro-people system oriented towards providing decent jobs to all its people would seek to bring these workers back into the labour force.

Discouraged workers are there in all capitalist countries, due to the chronic nature of unemployment in capitalism. For instance, in the USA, while the total labour force was around 163 million in 2019, the discouraged workers totalled 10.22 million.[32] In India, the number of discouraged workers is much larger, as the unemployment situation is far more worse. A rough estimate of the number of discouraged workers in India can be made by comparing the LFPR in India with the global average — the LFPR in India is less than the global average by around 11.3 percentage points (as per World Bank data given in Chart 2.4). Assuming that this difference represents the total number of discouraged workers in India (it is actually the number of discouraged workers in India above the global average), this figure works out to around 10.4 crore.[33]

Including the discouraged workers in the labour force and unemployed would send the unemployment rate through the roof! India’s unemployment crisis is among the worst in the world.

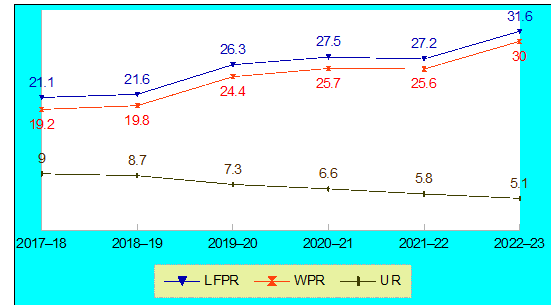

Women’s Employment

The godi media went ga-ga when the latest PLFS figures were released, as they showed that women’s employment, that has historically been very low in India, had actually increased during the Modi years, and the female unemployment rate had fallen to just 2.9 percent in 2022–23 (in usual status) — it was even lower than that for men (3.3 percent)! The data also showed that WPR for women as per usual status had significantly increased — by as much as 14 percentage points (see Charts 2.5 and 2.6).

Chart 2.5: LFPR, WPR and UR for Women of Age 15 years and Above (usual status, in %) [34]

Chart 2.6: LFPR, WPR and UR for Women of Age 15 years and Above (CWS, in %) [35]

A deeper scrutiny of the data reveals that it too suffers from the same infirmity as the general employment data given above — unpaid women workers have been included in the category of employed. In Table 2.7, we have given disaggregated data on the basis of employment status for women workers.

Table 2.7: Percentage Distribution of Women Workers

by Status in Employment (All ages, in usual status) [36]

| Self-employed | Regular wage | Casual labour | Total | |||

| Own-account | Unpaid Helper | Total | ||||

| 2017–18 | 20.2 | 31.7 | 51.9 | 21 | 27 | 100 |

| 2018–19 | 22.5 | 30.9 | 53.4 | 21.9 | 24.7 | 100 |

| 2019–20 | 21.3 | 35 | 56.3 | 20 | 23.7 | 100 |

| 2020–21 | 22.8 | 36.6 | 59.4 | 17.4 | 23.2 | 100 |

| 2021–22 | 25.4 | 36.7 | 62.1 | 16.5 | 21.4 | 100 |

| 2022–23 | 27.8 | 37.5 | 65.3 | 15.9 | 18.8 | 100 |

The data show that the number of women unpaid self-employed workers as a percentage of all women workers is much more than that of men unpaid workers: in 2022–23, women unpaid self-employed workers constituted 37.5 percent of all women workers, while for men, this figure was 9.3 percent.[37]

We recalculate the WPR and unemployment rate for women workers using the same methodology adopted for all workers above — by excluding the unpaid women workers from the category of employed, and including them in the unemployed. The reworked data is given in Table 2.8 and Chart 2.7. The results are eye-popping — the unemployment rate for women workers for 2022–23 in usual status shoots up to 39.2 percent, more than 13 times the official PLFS unemployment rate for women workers (2.9 percent).

While the official data show the women’s unemployment rate to have fallen from 9.1 percent to 5.1 percent, the recalculated data after exclusion of unpaid workers shows the unemployment rate to have risen from 35.4 percent to 39 percent over the period 2017–18 to 2020–21, then slightly declined to 38.7 percent in 2021-22 before further increasing to 39.2 percent in 2022-23. This data is in accordance with the discussion in the previous chapter that the economy slowed down till 2019–20, collapsed in 2020–21, and then has had an anaemic recovery during the post-pandemic period.

Table 2.8: Recalculated WPR and UR for Women of All Ages (usual status, in %)

| Official WPR | Recalculated WPR | Official LFPR | Official UR | Recalculated UR | |

| 2017–18 | 16.5 | 11.3 | 17.5 | 9.1 | 35.4 |

| 2018–19 | 17.6 | 12.2 | 18.6 | 8.7 | 34.4 |

| 2019–20 | 21.8 | 14.2 | 22.8 | 7.3 | 37.7 |

| 2020–21 | 24.2 | 15.3 | 25.1 | 6.6 | 39 |

| 2021–22 | 24 | 15.2 | 24.8 | 5.8 | 38.7 |

| 2022–23 | 27 | 16.9 | 27.8 | 5.1 | 39.2 |

Chart 2.7: Unemployment Rate for Women: Official and Recalculated (usual status, %)

Table 2.8 also reveals that employment rate for women (WPR) is abysmally low — just 17 percent of women are engaged in some economic activity that provide them with an income. This figure is among the lowest in the world. Women employment rates for other BRICS countries are more than double India rates: Brazil – 40 percent; China – 59 percent; Russia – 52 percent; and South Africa – 30 percent. According to the ILO, female WPR for Low Income Countries is 53 percent; for sub-Saharan Africa is 55 percent; and the world average is 43 percent. India’s female WPR is even lower than that for Saudi Arabia (23.6 percent).[38]

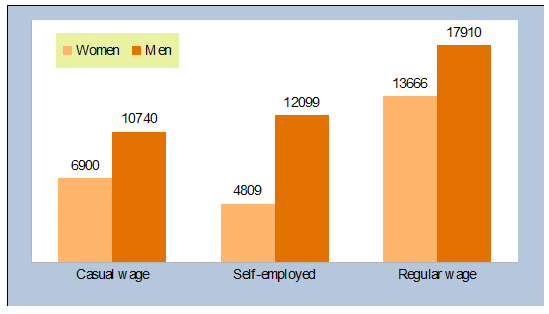

Even though WPR for women is low, it has increased by more than 5 percentage points over the period 2017–18 to 2022–23. To understand the real reasons for this increase, we give in Table 2.9 the percentage distribution of all women workers by status of employment, after shifting the category of unpaid self-employed workers to unemployed. And in Chart 2.8, we give the average monthly earnings by gender for the three categories of employment for 2021–22 from PLFS survey data. The starkest difference is seen in self-employment with women reporting earnings only 40 percent that of men.

Table 2.9: Percentage Distribution of Women Workers by Status in Employment

after Excluding Unpaid Workers (All ages, usual status, %)

| Self-employed, Own-account | Regular wage | Casual labour | Total | |

| 2017–18 | 29.6 | 30.8 | 39.6 | 100 |

| 2018–19 | 32.6 | 31.7 | 35.7 | 100 |

| 2019–20 | 32.8 | 30.8 | 36.5 | 100 |

| 2020–21 | 36.0 | 27.4 | 36.6 | 100 |

| 2021–22 | 40.1 | 26.1 | 33.8 | 100 |

| 2022–23 | 44.5 | 25.4 | 30.1 | 100 |

Chart 2.8: Gender Gap in Earnings for Different Kinds of Employment, 2021–22 (in Rs.) [39]

Table 2.9 makes clear that WPR for women has increased (by 5.6 percentage points in our recalculated data given in Table 2.8) because of an increase in self-employed women — their number has increased by a huge 15 percentage points (from 29.6 percent in 2017–18 to 44.5 percent in 2022–23). This increase is mirrored by a steady decline in the percentage of women in regular employment as well as in casual labour. Despite the average monthly earnings for women in self-employment being only Rs. 4,809 in 2021–22 — a wage that can only be called starvation wage — why has the number of women in self-employment been increasing? The decline in share of women in both casual labour and regular employment indicates that there has been no increase in job availability. It is because of the decline in job availability that there has been an increase in self-employment — it is basically distress employment, women are doing whatever low paid work is available to somehow stay alive.[40] Self-employment in India serves as a kind of reserve army of labour; when there are no jobs available, people do some or the other odd jobs to survive. Our data enumerators include all of them in the employed, even if the wages are destitution level wages.

Nearly 75 percent of the employed women are self-employed or in casual work. Even if we conservatively assume that half of them are earning below-subsistence level wages, and include them in the unemployed, it means that in India, real employment rate or WPR for women is just around 10 percent — not 16.9 percent as estimated in Table 2.8!

Therefore, it is not at all surprising that the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report for 2023 ranked India very low — 127 among 146 countries. The index measures gaps on four broad parameters (also called sub-indices) — economic participation and opportunities, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. India’s poor scoring on “economic participation and opportunities” for women contributed substantially to India’s low rank in the global list — India ranked 142nd (fifth lowest) on the sub-index of “economic participation and opportunity”.[41]

Youth Unemployment

Even PLFS data admits that youth unemployment rate is triple the overall unemployment rate (Table 2.10).

Table 2.10: LFPR, WPR and UR for Youth, Age 15–29 years (in %, usual status) [42]

| WPR | LFPR | UR | |

| 2017–18 | 31.4 | 38.2 | 17.8 |

| 2018–19 | 31.5 | 38.1 | 17.3 |

| 2019–20 | 34.7 | 40.9 | 15 |

| 2020–21 | 36.1 | 41.4 | 12.9 |

| 2021–22 | 36.8 | 42 | 12.4 |

| 2022–23 | 40.1 | 44.5 | 10 |

The India Employment Report of the ILO gives disaggregated data for youth by status of employment for the year 2021–22, based on PLFS data. We give this data in Table 2.11.

Table 2.11: Percentage Distribution of Youth (15–29 years)

by Status in Employment, 2021–22 (usual status) [43]

| Year | Self-employed | Regular wage | Casual labour | Total | ||

| Own-account | Unpaid Helper | Total | ||||

| 2021–22 | 19.2 | 28.3 | 47.5 | 27.8 | 24.7 | 100 |

In accordance with international standards, excluding the unpaid workers from the category of employed and including them in the unemployed, the actual employment rate for youth in 2021–22 falls to just 26.4 percent, and the actual unemployment rate rises to 37.1 percent, more than 3 times the official PLFS unemployment rate of 12.4 percent (Table 2.12).

Table 2.12: Recalculated WPR and UR for Youth (15–29 years),

2021–22 (in %, usual status)

| Recalculated WPR | Recalculated UR | |

| 2021–22 | 26.4 | 37.1 |

The India Employment Report points out that in 2021–22, the average monthly earnings or wages for youth in regular salaried work was Rs. 14,583, in self-employment was Rs. 10,100, and in casual work was Rs. 8,315.[44] The report also says that the percentage of youth in self-employment increased from 42.2 percent in 2018–19 to 47.3 percent in 2020–21 to 47.5 percent in 2021–22.[45] This increase has taken place, despite the average wage for self-employed youth being below poverty line wage.[46] The average wage for youth in casual work is nearly 20 percent less than this subsistence-level wage. All this only means that a very large number of youth in employment are actually underemployed / in distress employment, and should be included in the unemployed. This will send the youth unemployment soaring to more than 60 percent.

That there are no decent jobs is also borne out by another statistic from PLFS surveys highlighted by the India Employment Report. The youth unemployment rate increases with the level of education. In 2022, the unemployment rate among youth was six times greater for those who had completed secondary education or higher (18.4 percent) and nine times higher for graduates (29.1 percent) than for persons who could not read or write (3.4 percent).[47]

Notes

1. Economic Survey 2023–24, p. 1.

2. Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) is a survey conducted by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) under the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) to measure the employment and unemployment situation in India. It was launched in April 2017, after the Modi Government scrapped the previous five-yearly Employment and Unemployment Surveys conducted by the NSSO. The PLFS is conducted with a completely new data-gathering methodology.

3. Economic Survey 2023–24, Chart VIII.1, p. 273, Chart VIII.6, p. 276, and Chart VIII.7, p. 277.

4. Economic Survey 2023–24, pp. 158 and 274.

5. Our calculation. The workforce data of 56.5 crore is in CWS. {The Economic Survey does not explicitly mention this. We estimate that this data is in CWS. That is because it cannot be usual status data, as working backwards, the total working age population in usual status works out to just 1 crore (using WPR in usual status given in Table 2.2 of this chapter). This is less than the estimated total population of age 15 and above for 2021, which is 1.01 crore, as given in MoH&FW’s Population Projections 2011–36. [Table 17, Census of India 2011 – Population Projections for India and States 2011–2036, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, https://nhm.gov.in.]} We calculate the working age population from this figure and WPR (in CWS) from PLFS data given in Table 2.2 of this article (=56.5/51.8). Using this figure and LFPR in usual status (57.9 percent) given in Table 2.2, we can calculate the total labour force according to usual status, and then calculate the total unemployed using the Unemployment Rate in usual status.

6. Dhananjay Sinha, “Unravelling RBI’s ‘Unemployment’ Houdini Act”, 25 July 2024, https://thewire.in; P.C. Mohanan and R. Ramakumar, “Were 8 Crore New Jobs Created in Three Years?”, https://www.thehindu.com; Employment in the Country Increased to 64.33 Crore in 2023–24, Up from 47.5 Crore in 2017–18: KLEMS Database, Press Release, 22 July 2024, https://pib.gov.in.

7. P.C. Mohanan and R. Ramakumar, ibid.

8. NSSO, or National Sample Survey Organisation, is responsible for conduct of large scale sample surveys in diverse fields on All India basis. It is under the NSO.

9. Rosa Abraham et al., “A (Failed) Quest to Obtain India’s Missing Jobs Data”, 1 February 2019, https://thewire.in; James Wilson, “Lies, Deceit and Invented Truths in the Modi Regime”, 10 February 2019, https://www.telegraphindia.com; “2 More Members of NSC Quit on Feeling Sidelined”, 30 January 2019, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com.

10. Santosh Mehrotra and Jajati K. Parida, India’s Employment Crisis: Rising Education Levels and Falling Non-Agricultural Job Growth, October 2019, CSE Working Paper, https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in.

11. Source for table: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, available online at: https://mospi.gov.in.

12. India Employment Report 2024, ILO, p. 6, https://www.ilo.org.

13. “Maharashtra Police Receive More Than 11 Lakh Applications for 18,331 Vacancies”, 29 November 2022, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com; “Over 11 Lakh Applications for 4,644 Posts of Talathi in Maharashtra”, 21 July 2023, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com.

14. “Over 55 Lakh Candidates with BTech, MBA, Master’s Degree Apply for Group D Jobs in Uttar Pradesh”, 6 June 2023, https://www.businesstoday.in.

15. Subodh Varma, “Central Government: 22 Crore Applied, 7 Lakh Got Jobs, 9 Lakh Posts Still Vacant”, 31 July 2022, https://www.newsclick.in.

16. Nachiket Deuskar, “How Modi Government’s Warning About Private Economic Data Ends Up Highlighting Its Own Failures”, 24 January 2023, https://scroll.in.

17. Santosh Mehrotra, “Ten-Year Record on Employment: Does the Reality Match the Promises or Claims?”, 7 January 2024, https://thewire.in.

18. Nachiket Deuskar, op. cit.

19. Natasha Somayya K., “Unemployment Rate Ends High in 2023–24”, 5 April 2024, https://www.cmie.com.

20. “Unemployment Rate Rises to 9.2 percent in June 2024”, 1 July 2024, https://www.cmie.com.

21. C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh, “Faultlines in the Jobs Data”, Hindu Business Line, 19 October 2023, https://www.thehindubusinessline.com; Santosh Mehrotra, “Ten-Year Record on Employment: Does the Reality Match the Promises or Claims?”, op. cit. See also: “Work and Employment are Not Synonyms”, ILOSTAT, 29 October 2019, https://ilostat.ilo.org.

22. Source for table: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2017–June 2018, Table 38, p. A-231; Annual Report, PLFS, July 2019–June 2020, Statement 12, p. 53, and Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, Statement 6, p. 12, and Table 21, p. A-124; all available online at: https://mospi.gov.in.

23. Source for PLFS official data in table: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, ibid.

24. Our calculation. From population data given in MoH&FW’s Population Projections 2011–36 (Census of India 2011 – Population Projections for India and States 2011–2036, op. cit.), we have taken the total population figures given in Table 18, as the labour statistics in Table 2.4 are for all ages. The MoH&FW document gives data for 2021 and 2026. We calculate the CAGR for the period 2021 to 2026, and use it to calculate the working age population figure for 2022–23. That works out to 138.59 crore. Using this, and official LFPR data, we calculate the labour force = 58.76 crore, and then calculate the total unemployed.

25. Arun Kumar, “What the 23.9% Drop in Q1 GDP Tells – and Doesn’t Tell – Us About the Economy”, 2 September 2020, https://thewire.in.

26. We have discussed this in detail in Chapter 1.

27. India Employment Report 2024, op. cit., p. 28.

28. State of Working India 2023, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University, https://publications.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in. This report has based its calculations on the basis of PLFS data, various rounds. This report carries data till 2021–22. For 2022–23, data is taken from: Udit Misra, “ExplainSpeaking: How to Read India’s Latest Employment Data”, 16 October 2023, https://indianexpress.com. Also note that PLFS gives earnings data in CWS. The earnings are adjusted for inflation using CPI-R and CPI-U, base April–June 2022 quarter.

29. Prabhat Patnaik, “The Pervasiveness of Poverty in India”, 27 November 2023, https://www.networkideas.org. We use the poverty line data given in this for 2017–18, of Rs 8,400. The All-India Consumer Price Index Numbers for Agricultural Labourers on base 1986–87=100 has increased by 29.2% in 2022–23 over 2017–18. The poverty line for 2022–23 then works out to Rs. 10,853.[All-India Consumer Price Index Numbers for Agricultural Labourers taken from: All India General Index, Labour Bureau, https://www.labourbureau.gov.in.]

30. “’India’s Workforce Not Rising, Quality of Jobs Very Low’: CMIE’s Mahesh Vyas”, 2 May 2023, https://thewire.in; “Decent Work – ILO”, https://www.ilo.org.

31. Labor Force Participation Rate, Total (% of total population ages 15–64), World Bank Open Data, https://data.worldbank.org.

32. The Employment Situation – Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov.

33. We calculate this as follows. We estimate the working age population from population data given in MoH&FW’s Population Projections 2011–36 (Census of India 2011 – Population Projections for India and States 2011–2036, op. cit.). The working age population between age 15-64 years for the year 2022–23 works out to 91.97 crore. The average world LFPR is 66.3 percent. We don’t have LFPR for India for the age group 15–64 years, but World Bank gives this to be 55 percent as per Chart 2.4. This difference of 11.3 percent works out to a population of 10.4 crore.

34. Source for data: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, op. cit.

35. Source for data: ibid.

36. Source for data: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2019–June 2020, Statement 12, p. 53, and Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, Statement 6, p. 12; ibid.

37. Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, Statement 6, p. 12, ibid.

38. WPR calculation done by us, based on Female LFPR and Female UR data given in: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Sandra Tzvetkova and Max Roser, “Women’s Employment”, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org, accessed on 20 April 2024.

39. State of Working India 2023, op. cit. The report has based its data on PLFS 2021–22.

40. For more discussion on this, see: Ashwini Deshpande, “Illusory or Real? Unpacking the Recent Increase in Women’s Labour Force Participation in India”, 19 December 2023, https://thewire.in; State of Working India 2023, ibid., p. 53.

41. Global Gender Gap Report 2023, People’s Archive of Rural India, https://ruralindiaonline.org.

42. Source for data: Annual Report, PLFS, July 2022–June 23, Statement 2, p. 7, op. cit.; and Annual Report, PLFS, July 2019–June 2020, Statement 7, p. 47, Statement 9, p. 50, and Statement 26, p. 66, op. cit.

43. India Employment Report 2024, op. cit., pp. 268, 270.

44. Ibid., p. 85.

45. Ibid., p. 268.

46. Poverty line for 2021–22 works out to Rs. 10,164: Prabhat Patnaik, “The Pervasiveness of Poverty in India”, op. cit.

47. India Employment Report 2024, op. cit., p. 89.

(Neeraj Jain is a social–political activist with an activist group called Lokayat in Pune, and is also the Associate Editor of Janata Weekly, a weekly print magazine and blog published from Mumbai. He is the author of several books, including ‘Globalisation or Recolonisation?’ and ‘Education Under Globalisation: Burial of the Constitutional Dream’.)