Over 25 percent of India’s total land area has forest and tree cover, according to the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2023 conducted by the Forest Survey of India.

The said report was celebrated in a press release – titled ‘Forest and Tree Cover Grows, Fire Incidents Fall‘ – by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change on 27 December.

The country’s forest and tree cover combined now spans 827,357 sq km, the press release noted, accounting for 25.17 percent of the nation’s total land area. “Through innovative government initiatives and the involvement of local communities, India is not just protecting its natural resources but actively restoring them,” the press release claimed.

While this may appear to be a noteworthy achievement, the devil, as they say, is in the details. A closer examination of the report (which faced a year-long delay with no official explanation), and its data points, uncovers critical problems, highlighting why the reality is far more troubling than it appears.

What Counts as Forest?

Right off the bat, experts have long expressed dissatisfaction with the biennial report’s definition of ‘forest’. Speaking to The Quint, MD Madhusudan, ecologist and director of Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysuru, says,

“Over the 26 years from 1997 to 2023, reports have consistently claimed an increase in forest cover, yet for anyone with a general understanding of what constitutes a forest, this remains perplexing.”

In multiple instances, the 2023 report explicitly defines ‘forest cover’ as “all lands greater than one hectare, with a tree canopy density of 10 percent or more, irrespective of ownership, legal status, or land use. It also includes orchards, bamboo, and palm.”

‘Tree cover’, on the other hand, is defined as “areas with trees outside Recorded Forest Areas, ranging from a single tree to patches under 1 ha, including block plantations, linear plantations, and scattered trees not classified as forest cover in satellite data.”

Madhusudan explains why this is a problem. “For one, the report, for example, categorises oil palm and rubber plantations, which threaten natural forests, as part of forest cover. This redefinition of a forest to include activities that contribute to their destruction creates a paradox where forest loss becomes nearly impossible to describe.”

He adds, “If what replaces a forest after it is cut down is also termed a ‘forest’, can there ever be forest loss?”

In contrast, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s definition of a ‘forest cover’ explicitly states that a ‘forest’ excludes “land that is predominantly used for agricultural practices and urban development.”

MD Madusudhan says, “Every two years, the same narrative – of forest cover increase – is repeated, and as citizens, we accept it without sufficient scrutiny. This collective complacency is deeply concerning.”

Broad-Brushed Data and Contradictions

The problems with the report, though, run deeper than just the convenient definitions of forest cover and tree cover as experts point out how it only gives a partial picture of the state of India’s forests.

According to the ISFR, since the 2021 assessment, there has been a net increase of 156.41 sq km in the forest cover at the national level to 715,342.61 sq km in 2023.

Madhusudan says, “The net change in forest cover obscures the actual dynamics of forest loss and gain. For instance, while public forests may be degraded or lost in one area, gains may accrue elsewhere on private lands with tree cover.”

The report, for instance, makes no distinction or doesn’t provide any specific data on natural forests which support rich and diverse ecosystems in a way that plantations cannot.

“If you look at the report, you won’t know how much of it is natural forest, and how much is plantations, even though this is data that the Forest Survey of India should have,” says Soumitra Ghosh, researcher and activist based in sub-Himalayan West Bengal.

“Even in the Recorded Forest Area, not everything is forest,” adds Ghosh.

According to the ISFR, the Recorded Forest Area is “any area that is officially documented as a forest in government record.”

Simply put, this includes legal boundaries drawn on maps and used as references for decades. These boundaries don’t change regardless of what is actually present on the ground.

Even the report adds this caveat – “A Recorded Forest Area may, or may not, have tree cover.”

It is noteworthy that in 2024, Global Forest Watch, an international project that tracks forest changes in near real-time using satellite data and other sources, had noted that India actually lost 2.33 million hectares (2,330,000 ha) of tree cover since 2000 – equivalent to a six percent decrease in tree cover during this period.

Decoding the Data: Are India’s Forests Really Doing Better?

The forest cover of the country includes three types of canopies — Very Dense Forest (VDF), Moderately Dense Forest (MDF) and Open Forest (OF).

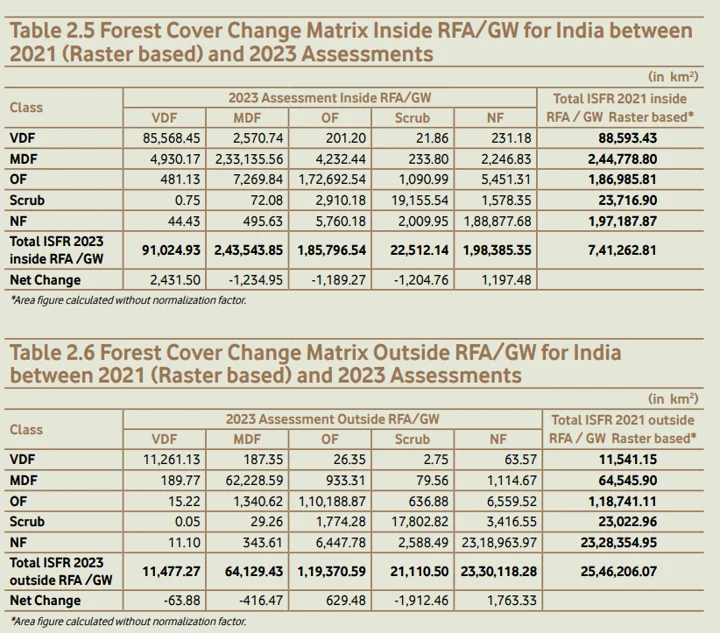

An important section in the report is the forest cover change matrix that gives information about how much a type of forest (such as VDF, MDF, etc.) has increased or decreased between 2021 and 2023 within and outside the parameters of the Recorded Forest Area.

This is valuable information that has unfortunately been codified in two confusing, vague tables with no additional explanation.

The report also combines data for Recorded Forest Areas and Green Wash Areas which are proxy digital boundaries created using satellite imagery where boundaries of Recorded Forest Areas weren’t available. The report also doesn’t specify how much of it is Recorded Forest Areas and how much is Green Wash Areas.

Here are some big points from the forest cover change matrix table – simplified:

- As per the report, in 2023, India’s Recorded Forest Area (including Green Wash Areas) stands at 741,262.81 sq km. However, of this, 197,187.87 sq km is classified as Non-Forest. This means nearly 200,00 sq km of Recorded Forest Area contains no forests – and could include other government, private, or institutional lands.

- Roughly 295 sq km of VDF became Non-Forest between 2021 and 2023.

- Roughly 44 sq km of Non-Forest inside the Recorded Forest Area and 11 sq km of Non-Forests outside became VDF between 2021 and 2023.

- Approximately 496 sq km of Non-Forest inside the Recorded Forest Area and 344 sq km of Non-Forest outside turned into MDF in the same time frame with no clear explanation.

It takes decades for a tree to grow to its maturity, let alone a full forest. According to experts, even if these numbers include plantations, such rapid growth seems unlikely. For instance, a coconut tree takes about 15 years to grow fully. A two-year-old teak sapling, on the other hand, takes about 20 to 30 years to reach full maturity as a tree.

“So, we have some incredible gains and some completely unexplained losses that no one has questioned so far. These are biological impossibilities,” says another ecologist who did not want to be named.

‘No Means of Verification’

There is also some peculiar discrepancy between the data in the 2021 report and the 2023 report.

Unlike the 2021 report, the 2023 report provides two separate tables for the forest cover change matrix – one for areas inside the Recorded Forest Area and one for areas outside it.

While the total geographical area in both reports is the same, the total area covered by VDF and MDF for 2021, as presented in the 2023 report, is higher than the figures reported in 2021.

The total area covered by Non-Forest and Open Forest, on the other hand, for 2021, as presented in the 2023 report, is higher than the figures reported in 2021.

(Data source: India State of Forest Report 2023 and the State of Forest Report 2021)

“It’s not clear how they arrived at this data,” says Ghosh. “There is no transparency in the process to determine how much of what is declared a ‘forest’ is actually a forest.”

According to the ISFR, the ‘forest cover’ data is captured and analysed using satellite imagery and reported accordingly.

While the report mentions that ground verification was conducted to validate the satellite data – and that maps and statistics were created based on these verifications – these documents have not been made publicly available.

Additionally, the report states that on-ground checks were carried out by the Forest Survey of India and state forest departments at 8,494 locations across the country – a notable increase from the 3,414 points visited in the previous cycle. However, details of these on-ground checks, such as their locations, selection process, and the outcomes of the checks, have not been disclosed.

“If they give the maps and locations, only then anyone else can go on ground and crosscheck. Some ground-level scrutiny by independent researchers in the past have shown that these tree covers exist on paper, but not always on the ground,” says Ghosh.

Soumitra Ghosh adds, “You also don’t have data on forest diversion either. There was a government portal that gave data on deforestation due to mining and urban development activities, but that has been stopped.”

“It is reasonable that some forests may need to be diverted for development or industry. However, what is crucial is transparency and disclosure about these diversions. Earlier reports provided such information, but this has now completely disappeared. The ISFR reports fail to reveal any details about forest diversions, leaving citizens completely in the dark about critical decisions on forest diversions,” says Madhusudan.

(Anoushka is a health reporter with the Quint, and covers health policy, medicine, mental health, and women’s health. Courtesy: The Quint. The Quint, launched in March 2015, is an Indian digital news and views platform.)