❈ ❈ ❈

Salaam, Indian Voters!

G.N. Devy

So much has already been said about the political outcome of Election 2024 in TV studios, newspaper columns, and stock markets and in conversations at homes, offices, and public spaces that it may seem that there is little to add. Yet, this election was so different from all previous elections, except the post-Emergency election of March 1977, that analysts, commentators, and historians will continue to discuss it for a long time to come.

In 1977, the Emergency loomed large over the election, and one just did not know what the outcome would be. Therefore, the stunning defeat of Indira Gandhi’s party resulted in spontaneous jubilation. For the 2024 election, the spread of communal hatred, fear of intimidation, and pervasive state surveillance generated by the regime for its decade-long rule formed the context.

From the hour the last EVM was sealed, exit polls on TV got busy in doling out the spectre of the return of an autocratic regime with unchecked power. But as the morning of June 4 progressed, and the election results started coming in, many voters heaved a sigh of relief, reminiscent of the 1977 results. Neither the hugely politicised Ram mandir nor the communal pitch of the BJP achieved their expected effect. Clearly, the Indian voter had decided to demonstrate its own judgment on the politics of hatred and fear. Though no single party secured a decisive majority and a hung Parliament was clearly on the horizon, several citizens were delighted by the results. They felt that a new hope for Indian democracy had emerged. What indeed was the nature of this hope?

The hope cannot be described in easy terms. Let me, therefore, allude to a poem by A.K. Ramanujan. It is titled “It does not follow, but when in the street” and talks about the experience of walking out of a jail. Ramanujan worked in Baroda in his early years of teaching. The street outside the Baroda Central Jail is lined with laburnum trees. In the hot month of May every year, they blossom. Ramanujan opened the poem with a picture of the bright yellow laburnum blossom, reflecting the joy in freedom. He contrasts the holes in his shoes and tattered clothes with his eagerness to return home: “at once I know / I have a sharp and young daughter / and an old age somewhere.”

Four shades of hope

The sense of relief that Indian voters experienced on the evening of June 4 was, as in Ramanujan’s poem, ambiguous, full of contradictions, and yet palpable. It was not so much a sense of accomplishment as it was a sense of hope, a feeling of assurance that there still is hope, for the people and for India’s democracy.

There were four major shades to the hope that returned to India. One, it was hope for the families whose members lost their lives due to the atmosphere of hatred and unreason. The list of thinkers, mediapersons, protesters, innocent citizens, and hapless Dalit and minority citizens who were silenced through muscle power or bullets can be very long. The families of these innocent martyrs as well as those who faced mob-lynching, expulsion, jail terms, social harassment, and mental agony, and those who sympathised with them, fought on their behalf, espoused their cause—all would have heaved a sigh of relief on June 4. So, too, the lakhs of farmers, political activists who participated in various agitations, and students who had to fight repression on their campuses, would have said: “well, at long last”. This was the hope for a relatively non-repressive state.

Two, the minorities in India were gripped with panic when the exit polls came out with fantasised numbers for the BJP, but were relieved when the actual results emerged. They knew that the Constitution has not timed out, that it will come to their rescue and allow them to continue to peacefully belong to their country. They saw the glimmer of hope for not having to publicly demonstrate their patriotism at every step.

Three, in the past 10 years, the States felt diminished while the Centre acquired an overwhelming role. While the Constitution describes India as a “Union of States”, the States with governments of other parties started getting stepmotherly treatment, and the States with BJP governments were glorified as “double engine sarkar”. The 2024 election has flatly rejected this attitude as non-acceptable. Voters in the largest States—Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, West Bengal, and Tamil Nadu—have clearly indicated that their interests cannot be entirely submerged in the interests of the Central government. The election results have helped India return to its constitutionally guaranteed federal structure. In fact, the hung Parliament arising out of the election results is a most powerful endorsement of Indian federalism.

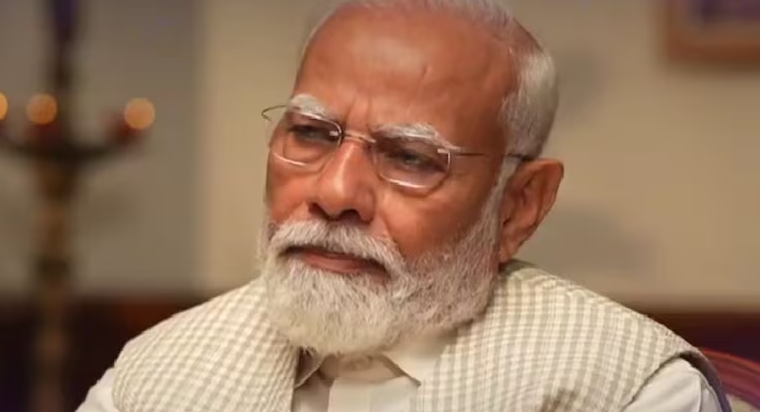

Four, the election seems to have brought back a breathing space for reason and science. Throughout the past 10 years, scientific temper was sidelined. Superstition and baseless claims to scientific achievements in ancient India had become a regular part of official discourse. Senior bureaucrats and top scientists too had to toe the line. It was not just the ouster of Darwin from school textbooks but also a systematic promotion of fraudulent claims aligned with a creationist view of the material world that made this regime rather unique. The election results indicate that metaphysical claims—such as having arrived into this world as a non-biological being—received a blank response from voters. That brings back a hope that the lost space of scientific temper may be regained in the coming years.

The sigh of relief heaved by the voters on June 4 had all these strands in it. People felt that a life of reason and decency may return to India, that the letter and spirit of the Constitution may still have space in India’s future, and arrogance and hubris of rulers can yet be tamed by the collective will of the people who form the very foundation of the country. Of course, no one should delude oneself by comparing the 2024 results with the 1977 results. The protagonists of the last regime stand diminished but not entirely replaced. There still is the question of the BJP’s conduct in the government formed through coalition. Will it have enough respect for its allies and also for the now enlarged opposition? Will it stick to the Parliament rule book from now on? Will it leave in peace individuals who raise dissenting voices? Will it become tolerant of criticism? And, most of all, will it accept communal harmony as the necessary condition for economic progress?

The country has to wait and see if it gets expected answers to these questions. Indian voters are a patient lot. They are capable of waiting for inordinately long periods; but when they know they need to assert themselves, they do so, quietly but fearlessly. The 1977 election had shown it. The 2024 election has reiterated it. Salaam, Indian voters!

(G.N. Devy is a writer and cultural activist. Courtesy: Frontline magazine, a fortnightly English language magazine published by The Hindu Group of publications headquartered in Chennai, India.)

❈ ❈ ❈

A Stunning Rebuke to Narendra Modi’s Divisive, Anti-Muslim Rhetoric

Saba Naqvi

“Love has illuminated my body

My inner self has brightened

My words now have the fragrance of musk”

—Kabir, 15th-century poet-philosopher from Varanasi

In the past decade, there appeared to be no limits to the exclusion-cum-violence, real and psychological, against India’s Muslims that the Narendra Modi regime and its ecosystem would not push. It seemed that many people did not care enough to oppose the segregation and profiling of minorities. It had, therefore, occasionally appeared to this commentator that the two-nation theory of Mohammad Ali Jinnah was being ghoulishly played out, as parts of India seemed to be a de facto Hindu Rashtra and a counter to Pakistan, an Islamic state.

We were embracing an ideology that diminished the ideas on which our independent nation was founded. It was not illogical to conclude that in the BJP-dominant parts of India, the nation’s largest minority was doomed as a people. Modi only reinforced these fears in the course of the 2024 campaign when he insulted and profiled Muslims in an almost manic way and sought to stoke fears about them snatching all the nation’s resources.

There appeared to be no end to the metaphorical and literal process of kicking an entire community on the backside, as a Delhi policeman infamously did to men bent in namaz (prayer) in the national capital on March 8.

The result of the 2024 election, therefore, is a seismic moment for Indian Muslims that restores faith in the fundamentals of democracy. Perhaps we can breathe easy again, take breath in and out in some comfort that all people can again be safe in their homeland. Not just Muslims, but the dissenters, the protesters, the media, the activists, and the ordinary citizens who dare to oppose.

The conversation has opened up in fascinating ways. One long message suggests that the open targeting of Muslims by the Prime Minister in many campaign speeches did not just scare the country’s largest minority; the words, casually thrown around about mutton, mangalsutra, Muslims, infiltrators, traitors, were heard loud and clear and repelled many Hindus as well. It also occurred to many voters to ask if this was all the mighty Modi had to say after a decade in power.

I, too, found anecdotal evidence of indifference and/or revulsion to the Hindu versus Muslim fulminations at the top. In 48 degrees Celsius heat on the Varanasi ghats during the last leg of the election campaign, a pundit told me that he worried about what Modi wants to turn him and his children into: “Are we to be the people whose identity and politics is to be decided by how much we can hate Muslims? Is that what our mantras and philosophy are about?” Prophetically, on the same day, the mahant of a temple in the city said that there was always a limit to some things. “This Hindu versus Muslim will not work. It will backfire.”

And then the result came, and a friend called from Varanasi where Modi’s victory margin had sharply come down. Our Kashi, he said, is the city of Lord Siva and of Sant Kabir; it is the home of Muslim weavers and Ustad Bismillah Khan; “Modi was just a visitor—for the last time.” He also shared the nugget that the Prime Minister had the narrowest lead in the Assembly segment where the Kashi corridor was constructed.

The huge hole in the BJP’s numbers came from Uttar Pradesh, and some BJP supporters have said that it was because all the State’s Muslims (20 per cent of the population) ganged up and voted with their hands and feet against Modi. Sure, Muslims voted against the BJP, but the sucker punch was delivered by Hindus for various reasons, such as their economic condition, the increased perception of Modi being a pro-rich figure (yes, electoral bonds were at the back of people’s minds), and Dalits choosing the INDIA bloc for the strategic reason of defeating the BJP.

The candidate selection of the Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Congress was excellent and increased the wind speed of the gathering storm that sought to protect the Constitution. Free rations, people decided, would not make them the bonded labour of the BJP, as a Dalit worker in Chandauli told me.

The greatest defeat

The greatest defeat came from Faizabad, which includes Ayodhya, where the SP’s Awadhesh Prasad, a Dalit candidate on a general category seat, trounced the mighty BJP. This will radiate, as it is the very site that has symbolised the party’s rise to power through the Ram Janmabhoomi agitation, the demolition of the Babri mosque and, in January this year, the inauguration of the Ram temple and puja by several VIPs, with Modi officiating as a sort of grand priest. The bluff has been called, and it turns out that people in Ayodhya were not blinded by the razzmatazz and spectacle. Even as their lands were acquired, their traffic blocked, and citizens pushed around, they were just biding their time to send a message to both Lucknow and New Delhi.

True, hate-mongering will not go away, and it is in the nature of the BJP and the RSS to flag divisive issues to gather their cadres and unite Hindu society over caste differences. They are ideologically committed to an Us versus Them ideology, as right-wing formations across the world are. They cannot biologically change their DNA, to use a prime ministerial turn of phrase. It is not over, the obsession with halal and hijab, Muslim this and Muslim that.

Still, the glass is half full, and I disagree with those who say it is empty. For there are arguments that it is all somewhat meaningless from the perspective of minorities, as the BJP-dominated narratives/atmospherics have resulted in many opposition parties not being able to openly speak up for Muslims or field Muslim candidates. True, the number of Muslim candidates who contested in 2024 fell to 78 from 115 in 2019.

Yet, there is something fabulous about the coalition of the poor that the SP-Congress forged with Dalits and EBCs added to their Yadav/Muslim voter blocs; it is this that would shift the ground from under the feet of the BJP. Indian Muslims have long understood that, with some exceptions such as Asaduddin Owaisi (of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen) repeatedly winning from Hyderabad, it is through coalition with other communities that their preferred parties can win.

In Uttar Pradesh, for instance, Mayawati’s BSP fielded the highest number of Muslim candidates at 20 but won zero seats, as the community’s vote overwhelmingly headed to the INDIA bloc. Post-election, Mayawati said that her party gave ample representation to Muslims but would think hard about repeating this to prevent huge losses in the future.

There is a message, too, from the Muslim-dominated Dhubri seat in Assam, won in the past by Badruddin Ajmal, AIUDF, who solely positions for Muslims. He was defeated by an amazing margin of 10 lakh votes by Rakibul Hussain of the Congress. The message in all this is that Muslims need not vote for fellow Muslims or parties that speak solely for Muslims.

Modi has been cut to size, but he is still Prime Minister and the BJP the single largest party with many State governments. The challenges remain, but the capacity to fight back has turned out to be robust despite the playing field not being level. Many problems persist, and new challenges shall emerge, but many of the winners of this round do have their futures entwined in also protecting minority rights. This also includes two parties, the JD(U) and the TDP, who could be pulling the strings in the third term of a Prime Minister who has turned out to be entirely biological.

(Saba Naqvi is a Delhi based journalist and author of four books who writes on politics and identity issues. Courtesy: Frontline magazine, a fortnightly English language magazine published by The Hindu Group of publications headquartered in Chennai, India.)

❈ ❈ ❈

A Clear Message

Sushant Singh

It was during his campaign speech at Banswara in Rajasthan that the prime minister, Narendra Modi, first claimed that the Opposition parties, if they won the general elections, would transfer the wealth, including mangalsutras, of Hindus to the ones who have more kids. This was a thinly-veiled insinuation against Indian Muslims. Coming from the prime minister himself, the speech had shocked most observers. The Election Commission of India did not do anything. It later explained its benevolence as a decision taken by the EC to “not touch” the “top two people in both the parties.”

The EC may have abdicated its duty, but the voters of Banswara didn’t. They defeated the BJP by a thumping margin, choosing the candidate of a tribal party, the Bharat Adivasi Party, which is a part of the INDIA bloc. In Banaskantha in Gujarat, Modi’s home state, he had threatened the voters that if they voted the Congress to power, it will take away one of their two buffaloes. Here, the Congress candidate, Geniben Thakor, had an unassailable lead and ultimately went on to win the seat. This was the first loss for the BJP in any Lok Sabha seat in Gujarat after 2009.

Modi’s campaign during these elections was neither about his record of the past 10 years nor about any promises for the next five. It was full of anti-Muslim vitriol and attempted to invoke fear among lower-caste Hindus that their constitutional benefits and wealth will be given away to Muslims by the Opposition parties if they captured power. This narrative, along with the construction of the Ram temple at the site of the Babri mosque that was destroyed by Hindutva’s foot soldiers in 1992 and the high-handed, security-centric approach towards the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir, was expected to pay rich dividends for the BJP. But that was not to be. Campaigning on a slogan of more than 400 seats for the ruling alliance and 370 for the BJP, Modi’s party has won a far reduced mandate. As I write this, the BJP still remains short of a majority on its own and is, therefore, dependent on two fickle allies — Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) and Chandrababu Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party —to form the government.

Since Modi became Gujarat’s chief minister for the first time in 2001, the BJP has never failed to get a brutal majority of its own in an election led by him. This Lok Sabha election is an exception. It will thus be a test of Modi’s skills to compromise with allies to run the government. It may no longer be a one-party, one-leader government that he will be heading; it will be a coalition government with its own pulls and pressures. These factors may or may not play out immediately but they are likely to surface sooner than later. That is the nature of politics.

Even though he is likely to be sworn in as the prime minister for a third term, Modi stands diminished as a political figure after yesterday’s result. He derives his legitimacy from a huge mandate, often credited to his ability to pull off miraculous poll victories against many odds. Once that sheen starts to wear off, as witnessed by the reduced margin of his victory in his own Varanasi Lok Sabha seat, questions are bound to be raised within the party and the larger sangh parivar. Tensions, which had been papered over in the last decade given the weight of decisive mandates in the past, can flare up and create unpleasant situations. It is not going to be a smooth ride for Modi in his third term as prime minister. His halo has diminished. When this happens, a halo often ends up becoming the proverbial noose.

Whether this election result is an outright rejection of his anti-Muslim campaign will be known in due course but it is a definite repudiation of the economic policies pursued by the Modi government. His economic policies were a disaster for vast masses of Indians, particularly the poor and the socially backward groups. Wealth and income inequality have risen sharply since 2014, unemployment has been at a record high, and price rise is hurting the ordinary people. These have been recorded in many surveys reported in the media but did not lead to remedial measures by the Central government, which was confident of sweeping the polls because of its ability to polarise Hindus against Muslims. But Uttar Pradesh and Bengal, among other states, have disrupted the BJP’s plan.

Modi was seen to indulge in crony capitalism and be insensitive to the pain of the poor. The five-kilogramme of free rations to 80 crore Indians has outlived its utility as a sop, with the people demanding jobs instead. Agnipath, the short-term contractual scheme for soldiers, exemplified the unemployment challenge and the government’s unwillingness to listen to grievances. The youth — particularly those belonging to the lower and the intermediate castes — in North India, which forms the traditional recruiting ground for the army, have spoken at the polling booth. Joblessness is a challenge that cannot be ignored by the next government.

The collapse of India’s mainstream media — print and television — created a vacuum that has been filled by independent platforms and YouTube influencers. Aided by cheap data, these voices have penetrated the Indian hinterland. The Opposition parties had neither the resources nor the media support to shape the narrative in their favour. But these new platforms came to the aid of the Opposition, and the BJP was found wanting for the first time in many years. Fresh from his gruelling Bharat Jodo Yatra, Rahul Gandhi was no longer the subject of mockery. He stuck to campaign issues and agenda points in an aggressive and sustained manner. Modi was compelled to respond to him, even making the blunder of calling Ambani and Adani corrupt.

The dry haystack was there; what lit the spark was Modi’s slogan for the NDA to capture 400 seats. It worried the lower castes that the call was to change the Constitution, which would result in the withdrawal of affirmative action policies. Their concern was not just about the material benefits of reservations. It was equally an expression of the need for political power, a quest for social respect, and a call for personal dignity. The electoral process, despite a biased EC, provided them the vehicle to express their view.

India’s democracy has been wounded and assaulted in the past decade. These election results have ensured that democracy will survive. But a lot more needs to be done to make it healthy, once again. Replacing a one-nation, one-leader rule with a coalition government will be the first step in the endeavour to heal India’s constitutional democracy.

(Sushant Singh is lecturer at Yale University. Courtesy: The Telegraph.)