On its 3,100-kilometre course from the mountains of Tibet to the Arabian Sea, the mighty Indus River flows through foothills and plains, national parks, lands that have been denuded of their forests, fertile farmland and bustling towns. Along the way are dams and barrages, with large hydropower and irrigation projects affecting the natural flow of the river.

The Indus provides almost 90% of the water for agriculture in Pakistan, but its waters can also take lives through floods. For the herders, farmers and fishers of the Indus basin, the river is a way of life, providing them with livelihoods and sustenance, yet it possesses the power to strip them of their homes, businesses and livestock with just one flood. They fear as well as revere the river.

Floods are an ever-looming threat in the Indus basin. Between 1950 and 2010, 21 major floods killed a total of 8,887 people, while immense floods in 2022 killed more than 1,700 and displaced nearly 8 million. The government estimated that an additional 8.4-9.1 million people would be pushed into poverty as a result.

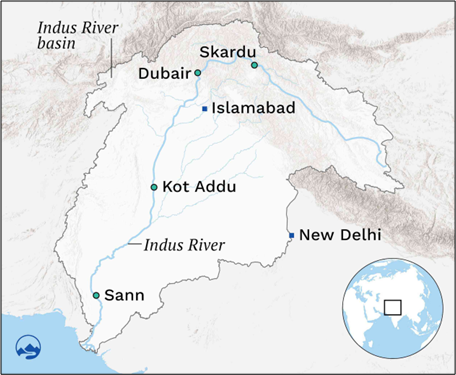

The Third Pole travelled down the Indus, from the mountains of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the north to the desolate villages of Sindh in the south, meeting people who depend on the river. We heard stories of a changing river and evolving relationships: many contend that engineering interventions like dams and barrages have transformed the Indus’ once free-flowing and predictable character, rendering it volatile and unforgiving. But almost nobody mentioned climate change, despite this being a key factor behind the unusually intense monsoon rains that caused the catastrophic 2022 floods.

The main locations visited by The Third Pole during its journey along the Indus River.

Credit: The Third Pole

‘Hits the poor the hardest’

Most people in Khaplu and Skardu towns, where the Shyok River meets the Indus in Gilgit-Baltistan, know of Muhammad Jan and the homes he runs for destitute children.

Muhammad Jan says that in this area, surrounded by towering mountains, the relationship between the Indus and its people is defined by fear and destruction. Here, most of the river’s water comes from glacial melt in the Karakoram mountains. But climate change impacts are jeopardising the food security and livelihoods of local people, increasing poverty levels.

“The people of this area are at the mercy of Indus. It hits the poorest the hardest,” says 57-year-old Muhammad Jan.

Muhammad Jan started supporting destitute children in 2002. More than two decades on, he houses 96 boys and 23 girls aged between 5 and 18 in homes called “Apna Ghar” – or “[our] own house” – in Khaplu and Skardu. “They are the children of shepherds or labourers or farmers living on slopes and terraces built along the Indus. They cannot afford one meal a day of roti [bread]. They do not own land and live in small one-room huts together with their animals and meagre belongings. They are at the mercy of nature.”

According to Muhammad Jan, the destruction caused when the Indus overflowed in 2010 was the worst in his memory, leading to many requests for admission to the Apna Ghar. Three brothers and one sister were admitted after their house was washed away by floodwaters in Balghar; they are all still studying, the eldest in college. He supported a girl whose father and three siblings died when their house collapsed as the Indus raged through Hoto village; she is now pursuing a degree in botany.

“I do not want them to live a troubled life because the Indus, in its various moods, has not been too kind to them,” says Muhammad Jan.

Effect of power project

Having cut through the Himalayan, Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountain ranges, the Indus reaches Kohistan district in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

“The Indus is an integral part of our landscape. Yet, we prefer to keep a distance from it due to its formidable force,” says 32-year-old Shams ul Haq, whose home is perched about 900 metres above the river in Kohistan, near a small hamlet called Dubair.

Ways to earn a living in Kohistan are limited, and residents are able to grow just enough maize, wheat and vegetables on their small, terraced farms to sustain themselves. Haq runs a development organisation to help residents acquire an education and set up small businesses. Floods have hit Kohistan four times since 2010, and in 2022, Dubair’s bazaar, located close to the river, was washed away. “The shop owners have abandoned the village and resettled in nearby larger towns,” says Haq.

Dubair is the location of the 130-megawatt Dubair Khwar hydroelectric project, which became operational in 2014. The village is also located 75 kilometres downstream of the under-construction 4,800 MW Diamer Bhasha dam, scheduled for completion in 2027, and 10 kilometres downstream of a 4,320 MW run-of-the-river dam being constructed at Dasu.

“Though we are surrounded by power projects, my village has power for only a couple of hours during the day. Our homes get electricity only at night,” says Haq. Most homes in Dubair are powered only by solar energy.

Haq explains that during construction of the Dubair hydropower project, local people willingly surrendered their agricultural land and even the village graveyard to developers to build infrastructure for the dam. They received what he considers to be “adequate compensation” for the land. However, many of these families then migrated to cities like Mansehra to establish new businesses there. As a result, he says, “the project has further impoverished the village”.

He hopes that when the Diamer Bhasha and Dasu dam projects are eventually completed, they will provide power to local villages and open up easy access to the rest of the country. “[I hope] more people come and inhabit Dubair, to liven up the markets.”

Life and death

Fifty-five-year-old Bashiran Bibi grew up on the Indus. Her ancestors lived on boats, travelling between Kalabagh in Punjab and Sukkur in Sindh, trading goods. In her childhood, she says, the river provided abundant water, food and trading opportunities for her family to thrive. “I learned to cook, eat and live on the boat. My family experienced life and death on the boat. We used to get off the boat only to bury the dead,” she recalls.

Then, after an array of dams and barrages were constructed in the mid-20th century to regulate the river’s flow and irrigate millions of acres of farmland on the fertile Punjab plains, the water level of the Indus fell. Meanwhile, fast-moving trucks on highways became the preferred mode of goods transportation. Bashiran Bibi’s family had to abandon trading along the river in the 1970s, as “the water became too shallow for our big boats, often 80- to 100-feet long.” Her family was forced to settle in Kot Addu in south Punjab, and take up fishing as their new profession.

A few minutes’ walk away from Bashiran Bibi’s house in the village of Basti Sheikhan – a dusty collection of mud huts and open courtyards – the Indus flows sleepily under the shadow of the Taunsa barrage. Fishing boats are tied up along the banks as children play in the muddy water.

Almost 40 years since Bashiran Bibi and her family resettled in Basti Sheikhan, they are still redefining their relationship with the Indus. “We had to learn to live in one place on land as opposed to being driven by the wind upstream and drifting with the flow of the water downstream,” she says.

Bashiran Bibi feels that the character of the Indus has changed tremendously since that time, “as if the free-flowing river has been tamed by dams and barrages”, which have cost her family their culture and identity.

But Bashiran Bibi still believes in the power of the Indus as a river of life, and in Hazrat Khizr – who is described in Islamic and other traditions variously as an angel, a mystic, and a saint. He is also known as the guardian of the river. She sings:

“Oh my beloved, the boat is ready,

Come, let’s go together across the river,

God will help us!”

‘I feel betrayed’

As a fisherman, Abdul Karim has spent his 60-plus years going with the flow of the Indus. He has lived on riverboats, eaten freshly-caught fish and drunk muddy river water. He says he could feel the warm, racing pulse of the Indus in the monsoon months, and remembers the pullah, a now-threatened species of fish, growing in abundance as water levels fell. “That was before the river betrayed us,” he says.

Karim still works as a fisher in the village of Sann in Sindh province, but he says the character of the river has been transformed. In the past decade, he says “the river has stopped following the familiar seasonal patterns. It swells and recedes unexpectedly.”

“It’s the government. It blocks water for electricity and to irrigate agricultural lands upstream in Punjab. The blockages reduce the level of water in our area of Sindh. Here, the land becomes dry and barren, and my community is unable to grow foods to sustain us. We have to live off fish, even if we have to catch them in the breeding season,” he says.

Karim is too poor to own a boat himself. He provides his services for PKR 500 ($2) per day to fellow fishers, who set out early in the morning to lay down the fishing nets and return to collect the catch before sunset.

Over thousands of years, the Indus has sheltered civilisations and washed them away too. Today, for the people living along its length, the river remains at the core of their lives.

As the Indus reaches its end, spreading shallow and wide across the delta in Sindh before vanishing into the Arabian Sea, the connection between the people and the river is at its strongest, “like nowhere else along the river,” according to Hassan Abbas, a prominent water expert currently focusing on water supply and drainage issues for Pakistan’s main cities.

Here, people revere and trust the river spirit, known as Udero Lal or Jhule Lal, Zinda Pir, Sheikh Tahir or Hazrat Khizr, depending on their religion. “We have altered the river’s natural flow. [But] we must never forget that nature’s power far surpasses that of humans,” says Abbas.

He adds that people used to coexist harmoniously with nature until engineering interventions began to make their mark: “The disruption in the flow of dissolved salts, suspended silt and water can be attributed to these structures, and this should be a matter of great concern.”

(Alefia T. Hussain is a Lahore-based journalist who currently works as a consultant editor for The Friday Times. Courtesy: The Third Pole, a multilingual platform dedicated to promoting information and discussion about the Himalayan watershed and the rivers that originate there.)