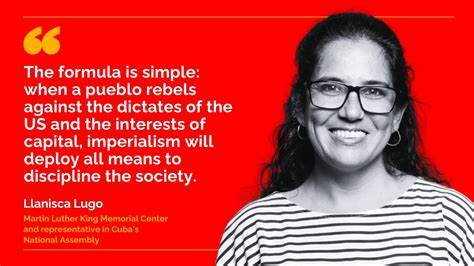

Cuba has endured a criminal U.S. blockade for over six decades, while Venezuela is nearing a decade of life under sanctions. The stated aim of the blockades against both countries is to promote “regime change.” Although the policy has not achieved its goal, it has generated numerous economic, social, and political challenges. In this interview, Llanisca Lugo, the International Solidarity Coordinator at the Martin Luther King Center in Havana, explores the consequences of the imperialist blockade as well as the strategies available to counteract the political and ideological impact of such unilateral coercive measures.

Cira Pascual Marquina: In a recent address in Caracas, you delved into the Monroe Doctrine [1823] and its historical connection to imperialist sanctions. Could you elaborate further?

Llanisca Lugo: It’s important to delve into the historical backdrop of imperialist policies directed at Cuba, Venezuela, and the region as a whole. These policies can be traced back to the Monroe Doctrine, which explicitly asserts the U.S. intent to dominate the continent. Implicit in this doctrine is the US’ drive to maximize profits with the least effort possible.

Over time, U.S. attempts to exert control over the region have shifted and adapted. The shifting balance of power between our liberation projects and the imperialist forces has determined policy changes, but the objective remains the same.

Let’s take Cuba as a case study. When you look at our history, you can see that the imperialist methods have changed over time. Initially, the U.S. sought to purchase Cuba from Spain. Subsequently, the U.S. strategically intervened in our war of independence [1895-98], despite Cuba’s near victory. This intervention paved the way for Cuba’s de facto recolonization. While nominally a republic, the island was effectively tethered to the economic interests and political dynamics of the U.S.

Then, shortly after the triumph of the Revolution [1959], when the Cuban people became the architects of their own history, the U.S. began to pursue a policy of collective punishment.

The formula is simple: when a pueblo rebels against the dictates of the U.S. and the interests of capital, imperialism will use all means to discipline the society. Before the Cuban Revolution, Havana’s hotels, ferries, and businesses catered to the Miami bourgeoisie. In fact, the island was functional to the interests of U.S. capital. Shortly after the Revolution came into power, the blockade was set in place to discipline the pueblo. The blockade was (and is) economic and financial, but it also generated political isolation.

A country—be it Cuba, Venezuela, or any other—that attempts to build a socialist society in a world dominated by capitalism and neoliberal globalization will, sooner or later, be “sanctioned” by imperialism. I should clarify that when I talk about imperialism, I tend to focus on the U.S., but imperialism is constituted by a network of economic, political, and cultural forces driven by capital’s financial logic with the U.S. at its head.

CPM: Why have unilateral coercive measures become a weapon of choice in the imperialist arsenal?

LL: The blockade does not feature in the story told by imperialism. Why? The idea is to transfer the responsibility for the problems in a blockaded country to its “bad” government. This is significant because, to the degree that the blockade diminishes the state’s efficacy, the institutions may seen as inept and incapable of governing and as exclusively accountable for the ongoing economic and financial crisis.

Of course, blockades never come alone. In Cuba, overt violence was deployed against the Revolution, but at present the blockade is the primary mechanism that imperialism uses. As a strategy, the blockade is a cultural and ideological mechanism that gives the U.S. an advantage.

CPM: You have argued that the blockade can, in some cases, sow division between the revolutionary project and the pueblo. Could you elaborate on this?

LL: Our situation is complex, because Cuba and Venezuela embarked on socialist projects in which the people are the protagonists. People’s power has been central, albeit in different ways, in both processes. Both Cuba and Venezuela recognize the pueblo as the subject of transformation, because it is understood that socialism is not possible any other way.

However, when the pueblo faces prolonged scarcity, then social fatigue, anomie, and apathy begin to emerge. This leads to a disconnect between the pueblo — the subject—and the revolutionary project. When this happens, tensions begin to emerge between the revolutionary power necessary for change and the project itself.

Since the state-as-a-revolutionary-power has to secure food for the people, produce essential goods, and assist vulnerable groups, that can weaken the strategic project. That’s why the situation requires constant monitoring.

In other words, we have to do everything possible so that the immediate problems don’t divert us from the strategic goal. That means that, while tackling scarcity and other economic problems, we also have to focus on the Revolution—which is always a work in progress—and address the shortcomings in our democratic processes. In short, we must pursue the project’s strategic objectives while addressing the immediate ones. Balancing both is crucial to prevent a gap from forming between the project and the pueblo.

The blockade restricts access to financial markets, hinders our relationship with banks, and delays vital deliveries of goods such as milk or even the fuel needed for hospital operations. When managing this complex situation, it’s difficult to sustain a political discourse about revolutionary construction, but it is imperative to do so.

In the Cuban case, which is the one I know best, significant efforts are made to engage in “what is to be done” discussions from a Marxist perspective—which is recognized as the ideological source of our revolution in the Constitution. Our debates also draw from the ideas of José Martí and Fidel. However, the blockade consistently obstructs progress, generating both economic and cultural pressures.

CPM: The stated objective of the blockades against our countries is “regime change.” Cuba has been subjected to a sanctions regime for over 60 years, while Venezuela has endured a nine-year blockade. Even so, our governments are still standing. So why does U.S. imperialism continue to pursue this policy?

LL: The blockade is deeply intertwined with U.S. domestic politics, particularly during election cycles. It transcends party lines, with both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party embracing the strategy. It should be noted, however, that Trump’s policies were perhaps the most draconian, because they hindered our capacity to get medical inputs and inflicted severe blows to our economy.

While the blockade has failed to topple our governments, it has effectively created a degree of social fatigue and apathy. Moreover, the blockade makes the younger generations more disconnected—the generations who didn’t experience the Revolution first-hand when the most profound social transformations were occurring and emancipatory epic and mystique were strongest.

It’s important to recognize that a revolution is never a finished product and can be reversed. A revolution is not always linear, it’s not in permanent ascent, and it can be undone. We have also learned that the downturns in a revolution can be much more painful, intense, and rapid than the advances, which are often slow because revolutionary transformations take strength and patience.

The disciplinary effects of the blockade have led some young people to entertain the notion that capitalism offers them better prospects, thereby eating away at their rebelliousness. Consequently, some Cuban youth aspire to enter a labor market defined by the logic of capital.

The logic of capital prevails when you think that you deserve more than the other person; that it’s normal to exclude some so that others can advance; that private enterprises work better; and that collective solutions wear you down.

Hence, we must engage in an ongoing debate about which societal model offers better living conditions for the pueblo. We have to show that a communitarian society will be better.

Why is this, from my point of view, so important? Because the blockade invisibilizes our history and our enemy. It creates a narrative in which the Revolution bears the blame for all woes, while successes and solutions seem to come from elsewhere.

If the youth, who haven’t experienced our revolutionary history firsthand, don’t have spaces to reflect, if they don’t have their organizations, if they don’t have a place to rekindle the mystique of the revolutionary spirit in their own terms… then we are at risk of losing sight of our collective struggle.

Finally, we cannot assume that our project is a finished one, that it is solid, homogeneous, and resistant in the face of imperialism. We are in a permanent struggle that must go hand in hand with permanent debate.

CPM: You have talked about the need to cultivate a revolutionary subjectivity among the youth. Beyond the ongoing debate that you encourage, which is crucial, what additional actions do you propose?

LL: Something that I often think about is that we should not imagine that there is a place full of perfect goodness, knowledge, and prophetic illumination. The idealized subject that we all dreamt of doesn’t exist. No individual has all the answers. Nor does anyone hold the perfect roadmap in their hands. Therefore, we must turn to the organized pueblo to find the way forward, but even the pueblo is not all-knowing.

We will make errors, and tensions and contradictions will inevitably arise, but that is the way forward. What lies ahead? We have to do more organizing and do it better. There was a time when the Cuban Revolution made huge strides because of widespread grassroots organization. That should be our model. We have to reactivate many of these organizations, nurture them, and help them advance.

But that is not enough. We must look for other ways to foster a collective subjectivity born out of rebelliousness. We should encourage a group of students who organize a congress or a bunch of barrio kids who gather to address a local problem. Such spaces should be allowed to flourish with autonomy, even if they are not following the exact paths that have been prescribed.

There are many ways of organizing; some are explicitly political, whereas others are not. Yet, we must refrain from discriminating against the latter. A group of young people organizing to play soccer may not be explicitly political, but their endeavor has a collective dimension that inherently goes against the logic of capital.

We have to inspire rebelliousness and enthusiasm among the youth, and we have to foster spaces that breathe life to our process. While doing this, we have to appeal to our history so that all merges into the revolutionary project… but each generation must forge its own path!

We have to debate and listen to each other, so that the diversity that emerges will also converge. It should not matter if it’s a party, a youth organization, or a commune; any organizational project that brings us together as a collective subject is emancipatory.

CPM: You recently visited Venezuela. Do you have any specific thoughts on the Bolivarian Process?

LL: Each process has its beauty. One of our pending tasks is to convey to the Venezuelan pueblo how important their process is for Latin America and the Caribbean. Indeed, the Bolivarian Process has had a huge impact on Cuba. When we listened to Chávez, we reconnected with our project in a new way, because he talked not only about national emancipation but also about continental emancipation.

We are also inspired by the Venezuelan communes. While they may not be perfect, it’s clear that when people organize themselves, collectively manage day-to-day affairs, and produce the goods they need, then a community of equals emerges. This is a fundamental step in transcending capitalism.

At the Martin Luther King Center, we are studying the Venezuelan communes and working to exchange experiences with communards. We want to learn about their processes of self-organization and self-management, about their interaction with the state, and about how they exert pressure, organize processes, and render accounts.

We have beautiful experiences in Cuba, but Venezuela’s communes can teach us a lot too.

As I said during a recent visit to Caracas, we should roll up our sleeves and go to the communes so that we may get to know and learn from each other. Nobody has all the answers; we can’t achieve emancipation alone. We must draw inspiration from every movement that aims to overcome capitalism and free our pueblos from the yoke of imperialism.

(Cira Pascual Marquina is Political Science Professor at the Universidad de Bolivariana de Venezuela in Caracas and is staff writer for Venezuelanalysis.com. Courtesy: Venezuelananlysis, an independent website produced by individuals who are dedicated to disseminating news and analysis about the current political situation in Venezuela.)