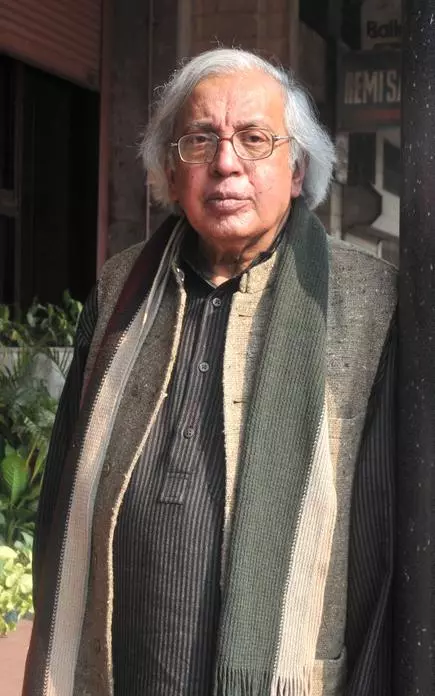

[As he turns 83 on January 16, Ashok Vajpeyi embodies the great values of the republic. Having lived the life of an extraordinary bureaucrat, when he set up a vast array of institutions, he is also a poet and patron of the arts. In his cosmos, poetry arrives with criticism, and literature finds meaning through a dialogue with music and visual and performing arts. As managing trustee of the Raza Foundation since 2001, Vajpeyi has taken this bridging role to its acme, with a prodigious calendar of seminars, concerts, exhibitions, books, and journals.

Engaged in constant dialogue with artists, writers, and thinkers across the country, he is among the foremost cultural-literary personalities to have emerged from the Hindi land since Independence, and one who has been a fearless critic of all tyrannies, whether of ideologies, markets, or fundamentalists. Excerpts from an interview with Vajpeyi.]

●●●

Ashutosh Bhardwaj: You began writing poetry and writing about poetry simultaneously. What prompted it?

Ashok Vajpeyi: Born in the small town of Sagar, I had learnt in my early teens that “poetry is good but tea is better”. The world in which I write poetry will always have things that are better or alleged to be better than poetry. I began with poets like Rilke, Neruda, and Pasternak and realised that to write poetry you require a certain courage to capture new experiences and sensibilities. Such courage was either mostly missing around me or was not visible. I came into contact with major Hindi poets like Agyeya, Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh, and Shrikant Verma. There was a provocation to supplement their poetic thought.

I had read American critics like Irving Howe, Harold Rosenberg, and Allen Tate, poet-critics Octavio Paz and Seamus Heaney, and was also influenced by the Polish critic Jan Kott, who wrote Shakespeare, Our Contemporary. I was convinced that it was not enough to write poetry, it was important to think and write about poetry and its relationship with the world.

AB: You wrote iconic critiques of Agyeya and Muktibodh in the mid-1960s when several veteran poets like Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Sumitranandan Pant, and Mahadevi Verma were alive. You did not write about them.

AV: I didn’t feel like it. Neither did I engage with Harivansh Rai Bachchan or Ramdhari Singh Dinkar. The two didn’t matter to me. Bachchan has good lyricism and Dinkar has an overdone audacity of a certain kind. They are, at best, good minor poets. They have little influence on the Hindi critical tradition. Their poetry suffers from an intellectual deficit. After the intellectual rigour and emotional depth of Kabir and Tulsidas, Jaishankar Prasad, and Nirala, Dinkar and Bachchan were a comedown.

AB: But Dinkar and Bachchan are influential outside Hindi literature. They are well known in the Indian English world.

AV: First, Indian English poetry, barring exceptions, has itself lacked intellectual rigour. The fiction writing has a certain intellectual strength, which is absent in most of its poets. Second, a large segment of the Indian English mind allows an intellectual rigour for itself but doesn’t look for it elsewhere. They have a hierarchical mind. They want to believe that what’s possible in English cannot be possible in Indian languages.

AB: What is the Ashok Vajpeyi school of poetry?

AV: I am a child, perhaps illegitimate, of literature. My life was shaped by literature. There are many sources of my poetry. I took Sanskrit in BA and studied Kalidas, Bhavabhuti, Jayadeva, and learnt about the sringara, or the erotic tradition, which was sidelined by Victorian values. I inherited the element of the erotic from the Sanskrit tradition, and the complexity of being human and the subtlety of existence from Western poetry.

Poetry is a genre as well as a reservoir of memory. A poetry which doesn’t remember and rehabilitate its ancestors is pointless for me.

Poetry is not an intellectual statement. It is not an emotional report. It’s not a visionary document. Yet it subsumes all of that to become poetry. Intellect and sensibility, vision and experience, questioning or interrogation or celebration—they all get organically coalesced into poetry.

I have also tried to discover and articulate a notion of earthly sacredness. There’s a sacredness in ordinary living. The erotic, the spiritual, and the cosmic share a space in my poetic muddle.

AB: The above elements shaped your poetry for the first 60 years. But a political reality suddenly arrives in your poetry after your retirement as a civil servant in 2001. What if you had been shaped by the political in your early days too?

AV: Yes, for a long time my poetry had an inward look, and outwardness came in only through an inward gaze. But the Babri Masjid demolition, my retirement from civil service, and the 2002 Gujarat riots brought about a discomfort. I realised that my poetry would be failing in its moral function if I don’t dig the outward into the inward. I can, however, cite any number of poems from my first 60 years that were provoked by political impulse except that it was not so direct that anybody could discern the political undertone.

AB: You consciously concealed it?

AV: I was a civil servant. I couldn’t have taken a direct political position, and yet I didn’t want what was happening to go unaddressed in my poetry. I adopted a poetics of indirection, which did not mean not addressing it either. However, 2002 onwards the earlier indirections were given up. My distrust of the direct statement has not completely disappeared, but I have tried to find a way to sideline it. I still don’t believe that poetry can be a statement, and yet my own poems have sometimes tended to become statements, in spite of me, because the situation cannot be addressed except by a direct statement. Poetry has to perform not only dharma, but also apad dharma (dharma appropriate to a time of calamity).

Being political doesn’t necessarily mean being more effective as a poet. Being a poet is already being a moral being. Jean-Paul Sartre once made the outrageous statement that writers should stop writing and go fight in Vietnam. Theodor Adorno said that there can’t be poetry after Auschwitz. But it was countered by saying that there should be poetry even after Auschwitz.

AB: There has always been a rift between the political and the personal in literature. How do you see this in Hindi?

AV: During Partition, the largest number of Muslims who migrated to Pakistan were from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. It must have created a social void. But there’s hardly any attempt in Hindi fiction or poetry to record the void after millions of your neighbours have gone away. Shani once raised the question, why are there no Muslim characters in a large part of Hindi fiction? Partition itself remains very inadequately addressed.

AB: Only a few writers wrote about Partition.

AV: And all of them from Punjab—Agyeya, Krishna Sobti, Bhisham Sahni, Krishna Baldev Vaid, Upendranath Ashk. At present, I am also outraged by the fact that 70 per cent of crimes against women, children, minorities, Adivasis take place in the Hindi belt. The RSS was created and dominated by Maharashtrians, but it no longer has so much support there. It [the BJP] has come to power largely because of the Hindi-speaking States. The Hindi belt has come to represent parochialism and fundamentalism. As a Hindi writer, I cannot ignore it. Literature in Hindi today can only be against Hindi society. There’s no other moral choice before a Hindi writer. Literature and society are pitched against each other.

AB: But it must also be recorded that Hindi society has not given the Hindutva ideology a single great writer. The Nazis could still showcase some writers but not Hindi.

AV: Yes. Hindi literature has been fairly secular. It has stood against hatred. Barring some exceptions, it has not promoted casteism, parochialism, and communalism. I had differences with the Marxists partly because their understanding of their own ideology was remarkably shallow and uninformed. But their ideology has offered a great dream and produced great writers. Then there are ideologies which are arid ab initio. Hindutva is one such political ideology. The RSS is now nearly 100 years old and also in power, but it has not produced a single great writer or intellectual. It cannot. It can only produce violent and aggressive mediocrity. Even in the Hindi belt, it has failed to attract a single significant writer to its fold.

AB: You mentioned the near absence of Muslim characters in Hindi fiction. But is not the vice versa also true? Where are the Hindu characters in Urdu fiction from Umrao Jaan Ada (1899) to Kai Chaand the Sar-e-aasman (2006)? The latter narrates a tale of two centuries across north India, but a reader might well believe it is taking place in an altogether Muslim land.

AV: Though Urdu claims the legacy of composite culture, the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb, there is a sad situation of mutual invisibility. Although Hindi has bridged the distance from Urdu, the vice versa does not seem to have happened.

AB: Tell us a bit about the institutions you helped set up in Madhya Pradesh.

AV: A lot of credit goes to the Madhya Pradesh government, which gave me the opportunity and freedom to undertake various initiatives. We began in the 1970s with an annual festival, Utsav, with poetry, theatre, dance, classical music, which created an audience in Bhopal. A decade later, Bharat Bhavan institutionalised Utsav in a permanent mode.

We also set up Kalidas Academy, Dhrupad Kendra, Adivasi Lok Kala Parishad, and residencies in the name of Premchand, Muktibodh, and Nirala. Each was democratic to the core. J. Swaminathan, for instance, firmly opposed neo-narrative art and attacked it intellectually, yet, as a major figure at Bharat Bhavan, created the single largest public collection of neo-narrative art in the 1980s. While in Bhopal, he created a new vision of visual arts in which folk and tribal and urban were equally valid expressions of contemporary art. B.V. Karanth took us back to the dialects of Hindi like Bundelkhandi, Malwi, and Chhattisgarhi and produced the first full-length plays in these dialects.

In its first year, more than a lakh people visited Bharat Bhavan. At that time, visitors to National Museum, National Gallery of Modern Art, and Crafts Museum were less than a lakh.

The idea of staging the Mahabharata took shape in Peter Brook’s mind after his visit to Bharat Bhavan. When he staged it in an abandoned stone quarry at Avignon, he invited me to the inaugural show.

We also organised the World Poetry Festival in 1989, which was attended by 27 foreign poets including giants like Stephen Spender, Tomas Tranströmer, Ernesto Cardenal, Nicanor Parra, Roberto Juarroz, and Craig Raine.

AB: You have been engaged in a passionate argument with Leftist writers in Hindi for several decades. How did it transform you?

AV: First, it made me aware that my insistence on individuality would have greater acceptance if I was able to couch it in social terms. This is a clever lesson. Some of the best progressive writers like Muktibodh and Shamsher Bahadur Singh have very individual voices. Two, there are issues and problems in society which can’t be ignored and bypassed by literature. Three, I don’t have the talent or necessary skill to try a certain form of literature, but if somebody else does it, I must not fail to acknowledge it. Four, whatever may be the consequences of a dialogue with your adversary, you must not cease to be in dialogue.

AB: You are among the few writers to have constantly engaged with other art forms. Before you turned 20, you wrote a poem after listening to Ali Akbar Khan on the radio, a poem on M.F. Husain’s painting after a reproduction appeared in the Hindi journal Kalpna, a poem on Khajuraho, and so on.

AV: I learnt quite early that the truth of literature is different from the truth of visual art which is different from that of music. And yet, they share certain elements. All of them have rhythm, and yet what rhythm does in poetry is quite different from what it does in music or in the visual arts. The struggle of Muktibodh is not more important than the struggle of Kumar Gandharva or Habib Tanvir. Literature is not a vocation to be pursued singly but is part of a larger community of arts.

I was intrigued by what a painting does but a poem can’t. At a softer level, I don’t agree with ekam sad, vipra bahudha vadanti (literally, there is only one truth but it is called by many names) because literary truths are distinctly different from musical truths or from visual artistic truths. If they were all similar, why would we have so many arts?

Singularity of truth also leads to autocracy. The plurality of truth saves the truth from itself, makes it democratic.

AB: Can we differentiate among these truths as well as the various languages these arts use to depict their truths?

AV: That all these forms have a distinct language is true in a very broad sense. When you come to a complex analysis, the word gets primacy by sheer usage. One of the problems in talking about the arts is that it uses verbal language. Since writers have command over the verbal language, they tend to overvalue and valorise verbal communication at the cost of other forms of communication. But chitraarth, rangaarth or nrityaarth (the essence of a painting, or of a dance form) can’t be just versions of or approximate vaagarth (the essence of the spoken word).

The advantage of the verbal should be employed for a better understanding of the other forms and the differences with them. Differences enrich the creative spectrum.

AB: How does a painter bring poetry to the canvas?

AV: There are several approaches. One, painters like Krishen Khanna, M.F. Husain, J. Swaminathan, who were fond of poetry, who said their paintings were inspired by poetry.

The second category is rarer. You have S.H. Raza who inscribes lines of poems— from the Upanishads or Bhakti, Urdu, and modern poets—on his canvases; not treating them as illustrations of the paintings or akin to the painting. He’d say, ‘the verse has nothing to do with what I am painting. Nor am I painting to illustrate the verse’. Raza would say a verse flashed before him when he was painting. It may or may not have any relation to the painting. The poem is allowed to exist on its own.

The third kind would be painters like V. Ramesh and Atul Dodiya who use whole poems on their canvas.

AB: The fusion of various arts is reflected in the Raza Foundation. You have published significant books, instituted fellowships and awards, and organised a range of events and seminars. But there is no second or third generation leadership at the Raza Foundation. Why?

AV: Our mandate can only be implemented by someone well versed in all the arts. In all humility, I don’t know of many writers who would be as interested in other arts. There might be some exceptions, but by and large writers have become unconcerned and uninformed about other arts.

It is a difficult proposition to find the right people. This was not always so. There was a dialogue between painters and writers in the 1960s and 1970s. Unfortunately, it no longer happens. I remain on the lookout for people.

AB: What are the duties of a writer in these violent times?

AV: Let us not forget that we have been a violent people. Non-violence has been a parallel, minor tradition led by Buddha, Mahavira, Bhakti poets, Gandhi. But the main tradition, as it looks to me now, has been of violence. Now, besides violence, hatred and lies have become rampant. This is a great civilisational collapse. For a writer, it’s a duty of despair.

When religions, especially Hinduism, seem to have become devoid of spirituality and are open promoters of violence and hatred, it is the job of literature to retrieve spirituality from the clutches of religion. A writer must reconstruct and preserve memory and safeguard it against attempts to impose a concocted memory. Literature is the last residence of spirituality in our times.

A writer cannot cooperate with the forces promoting violence but must endeavour to create a climate of disobedience and non-cooperation. Literature must zealously protect its autonomy and defend its realm against those trying to undermine it, be it politics, religion, ideology, or the state. It is a tall order. But literature must have a tall order. It cannot be a camaraderie of pygmies. It must be a space of excellence that upholds the highest forms of morality. A writer must be willing to walk alone. This should not depress them. This is their calling.

(Ashutosh Bhardwaj is an independent writer and journalist. His recent book, ‘The Death Script’, traces the Naxal insurgency. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)