Budget 2023–24: What Is in it for the People?

Part 8: Education Budget

Neeraj Jain

New Education Policy 2020

The Modi Government declared its perspective towards education in the New Education Policy that it unveiled in 2020, that has come to be known as NEP-2020.

The very process of announcing NEP-2020 reveals many things. On 29 July 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic causing existentialist crisis for millions of people, suddenly the nation was told that the central cabinet, presided over by the Prime Minister, has given approval to the National Education Policy 2020. Notably, education is in the Concurrent List (List III) under Article 246 (Seventh Schedule) of the Constitution, i.e. it is a subject that concerns both the centre and the State/UT governments equally. Despite this, the Centre rushed to implement NEP-2020 without (a) seeking the opinion of the Central Advisory Board on Education (CABE) – the highest body for policy scrutiny and approval wherein all the State/UT education ministers are duly represented; (b) debate and endorsement in the State/UT Vidhan Sabhas; and (c) scrutiny by the Department-Related Parliamentary Standing Committee followed by approval of the Parliament.

Discussing the ideology of the NEP-2020 and its contents in detail is beyond the scope of this article. We nevertheless discuss some aspects of the NEP in the context of the education budget proposals of NEP.

Modi Government’s Educational Spending Since 2014

Education is fundamental to human as well as societal development. That is why in all developed countries, governments have taken the responsibility of providing Free, Equitable and Good Quality school education to ALL their children (the private sector invests only for profit). Developed countries spend considerable amounts on providing good and equitable quality education to all their children. The 27 countries of the European Union spend 5.1% of GDP on education, the OECD countries spend 5.3% of GDP on education, and the world average is 4.3% (Data for 2020).[1]

In India, unfortunately, successive governments at the Centre have never really prioritised education spending in their budget allocations. Despite the Kothari Commission recommending way back in the 1960s that education spending of the General Government (that is, Centre and States combined) should be increased to at least 6% of GDP, it has continued to languish at between 3 and 4 percent of GDP for the last several decades.

More than these total spending figures, a more accurate comparative picture of cross-country public spending on education is provided by per student public spending on education — and this is actually what matters. India’s public spending on education per student is around 25 times less than that of the developed countries![2]

With the Centre and States not willing to provide sufficient funds to provide good quality education to all children, this created the conditions for the gradual privatisation of the school education system. Till the 1980s, the overwhelming majority of the schools were government schools; private unaided recognised schools constituted less than 10% of the total schools in the country.[3] By 2014–15, when Modi came to power, private recognised unaided schools accounted for 19% of all schools (primary to higher secondary) and 33% of student enrolment (Classes 1–12). [4]

Consequently, the education system of the country was in a dismal state at the time of the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. This becomes evident from just a single statistic: the 2011 Census figures, the most reliable data source in the country, showed that of the 20.8 crore children in the age group 6–13 in the country, 3.2 crore or 15.4% children had never attended any school![5] That is huge.

In its manifesto for the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP promised to rectify this situation and increase spending on education to 6% of GDP. The NEP-2020 too affirms that the “Centre and the States will work together to increase the public investment in education sector to reach 6% of GDP at the earliest”.[6]

However, like all its other election promises, this too has turned out to be a jumla. The Economic Survey 2022–23 admits that total education spending of the general government (Centre + States) continues to languish at a mere 2.9% of GDP (2022–23 BE). The Economic Survey data on education spending includes spending on sports, art and culture; so actual spending on education would be even less. This figure is among the lowest in the world.

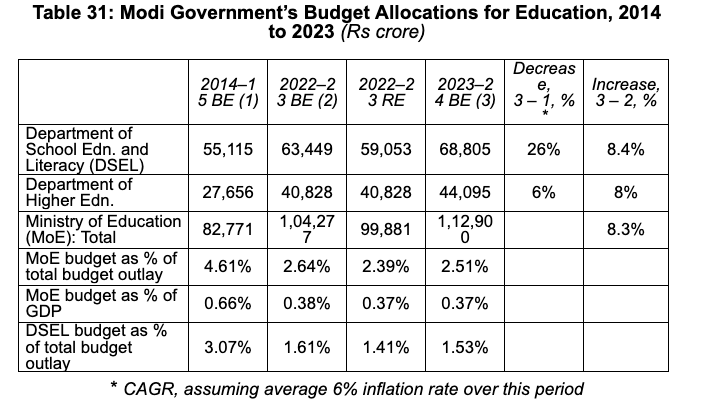

Not only that, in its 10 budgets presented so far, the Modi Government has made deep cuts in its already low education spending. As a percentage of budget outlay, total budget of the Ministry of Education has nearly halved during the Modi years — from 4.61% in 2014–15 BE to 2.51% in this year’s BE. And as a percentage of GDP, it has fallen from 0.66% to 0.37% (Table 31).

Budget 2023: School Education

NEP-2020 on School Education

When it comes to bombast, the Modi Government is second to none. The NEP-2020 document contains a lot of flowery rhetoric about the necessity of improving quality and infrastructure of government schools to bring back to school all school-going children and achieve 100% Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) up to secondary level. The document says:

“A good education institution is one in which every student feels welcomed and cared for, … where a wide range of learning experiences are offered, and where good physical infrastructure and appropriate resources conducive to learning are available to all students. Attaining these qualities must be the goal of every educational institution….

“One of the primary goals of the schooling system must be to ensure that children are enrolled in and are attending school. As per the 75th round household survey by NSSO in 2017–18, the number of out of school children in the age group of 6 to 17 years is 3.22 crore. It will be a top priority to bring these children back into the educational fold as early as possible, and to prevent further students from dropping out, with a goal to achieve 100% Gross Enrolment Ratio in preschool to secondary level by 2030.

“There are two overall initiatives that will be undertaken … The first is to provide effective and sufficient infrastructure … Besides providing regular trained teachers at each stage, special care shall be taken to ensure that no school remains deficient on infrastructure support. The credibility of Government schools shall be re-established and this will be attained by upgrading and enlarging the schools that already exist, building additional quality schools in areas where they do not exist, and providing safe and practical conveyances and/or hostels …

“The second is to achieve universal participation in school by carefully tracking students, as well as their learning levels, in order to ensure that they (a) are enrolled in and attending school, and (b) have suitable opportunities to catch up and re-enter school in case they have fallen behind or dropped out.

“Once infrastructure and participation are in place, ensuring quality will be the key in retention of students …”[7]

As the above extracts show, NEP-2020 lays considerable emphasis on improving school infrastructure, increasing the number of schools, and providing adequate regular teachers, to ensure that the 3.22 crore children of school going age who are out of school are brought back to school, and to ensure that drop-outs do not occur in future.

Claims and Reality

i. Budget Cut in School Education

Implementing the recommendations of NEP-2020 requires a huge increase in budgetary spending on school education.

However, shockingly, in the ten budgets presented by the Modi Government since it came to power in 2014, it has reduced its spending on school education by a quarter! The budget outlay for this year is lower than the BE for 2014–15 by 26% in real terms (CAGR, assuming inflation of 6% per year).

The depth of the cut in the school education budget is better reflected in another statistic — the budget of the Department of School Education and Literacy as a percentage of total Union Budget outlay has halved since 2014. It was 3.07% in 2014–15 BE, and has fallen to 1.53% in this year’s BE (Table 31).

The Modi Government wants to make India ‘Vishwaguru’ without spending on educating its children!

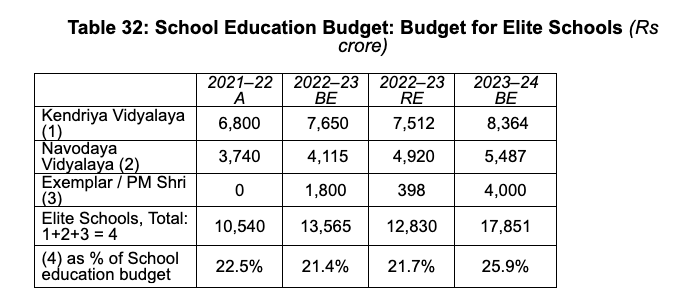

ii. Elite Schools

In 2022, the Centre launched an ‘Exemplar’ scheme to upgrade 15,000 schools to ‘high quality schools’ over the next five years. The Education Minister forgot that all such initiatives have to be credited to our narcisstic Prime Minister; this year, the mistake has been rectified and the scheme has been renamed as Pradhan Mantri Schools for Rising India (PM SHRI schools). The school education budget document says that the aim of developing these “schools of excellence” is to “showcase the implementation of the National Education Policy 2020”. At this speed of upgradation, it will take at least 200 years to upgrade the more than 10 lakh government schools in the country, provided we do not open any more schools during this period. Clearly, all the florid talk in the NEP about providing good quality education to all children is only another jumla.

Whether the government will be able to upgrade even 15,000 schools is difficult to say, as the government has imposed the condition that it will open PM Shri schools in only those States that accept NEP in totality; this is thus a roundabout way of imposing NEP on States. Another condition is that the Centre will fund these schools only for 5 years, after which the States will have to fully fund these schools. Given their constrained budgets, how many States will be willing for this is to be seen.[8]

Last year, of the total budgetary allocation for PM Shri, barely 20% was spent; this year, the budget allocation has doubled from last year’s BE to Rs 4,000 crore. Since the scheme proposes to develop 15,000 schools over 5 years, we can assume that this year 3,000 schools will be developed into PM Shri schools. Two other categories of schools on which the government spends a significant amount of its school budget are the Kendriya Vidyalayas and Navodaya Vidyalayas (Rs 13,851 crore in 2023–24 BE) (Table 32). There are presently 1,252 Kendriya Vidyalayas and 643 Navodaya Vidyalayas in the country. These three categories of elite schools total nearly 5,000 schools, and constitute 0.5% of the total government and aided schools in the country (11 lakh). Assuming each PM Shri school will have 1,000 students, this means that total students enrolled in these 3 types of elite schools will be 45 lakh — this number is just 2.7% of the total 16.7 crore students enrolled in all government and aided schools.[9] Adding up the allocation for these three categories of elite schools, this means that for 0.5% schools where 2.7% of the total children are enrolled, the Centre is proposing to spend 26% of the Union school education budget; while for the remaining ordinary government schools, which constitute 99.5% of the total government schools and where 97.3% of the total students are enrolled, it proposes to spend only 74% of its already low school education budget.

iii. Decline in Number and Quality of Teachers

The introduction to the NEP 2020 has a lot of blah-blah-blah about the importance of good quality teachers. It recognises that “the teacher must be at the centre of the fundamental reforms in the education system”. It says that we “must re-establish teachers, at all levels, as the most respected and essential members of our society”. The NEP “must help recruit the very best and brightest to enter the teaching profession at all levels, by ensuring livelihood, respect, dignity, and autonomy …”[10]

But it is all a lot of hot air.

One of the biggest problems afflicting the school education system is shortage of teachers. While the NEP pontificates of the need to make available adequate number of teachers for schools, the ground reality is that government schools are plagued by a huge shortage of teachers:

- Of the total primary schools in the country (all managements), 9.57% schools are single teacher primary schools — implying that 80,000 primary schools in the country have only one teacher! The overwhelming number of these are government schools — more than 70,000! Equally staggering is the fact that even among the upper primary, secondary and higher secondary schools in the country, 25,000 schools are single teacher schools (data for 2017–18).[11]

- Since then, the government has stopped releasing data on single-teacher schools. But in response to a parliamentary question, the Minister for Education replied that in 2021–22, there were 1,17,285 one-teacher schools in the country.[12] In just four years (2018 to 2022), the number of single teacher schools has gone up by 11.4%! No wonder that UDISE has stopped releasing data on single teacher schools.

- More than 70 percent primary schools (all managements) had three or less than three teachers (data for 2015–16, after which the government has stopped releasing such data).[13]

But the Modi Government is totally unconcerned. Despite such a massive shortage of teachers, the number of teachers has declined in government schools during the Modi years (2016–17 to 2021–22) by a huge 1.15 lakh (data is not available after 2021–22) (see Chart 7).

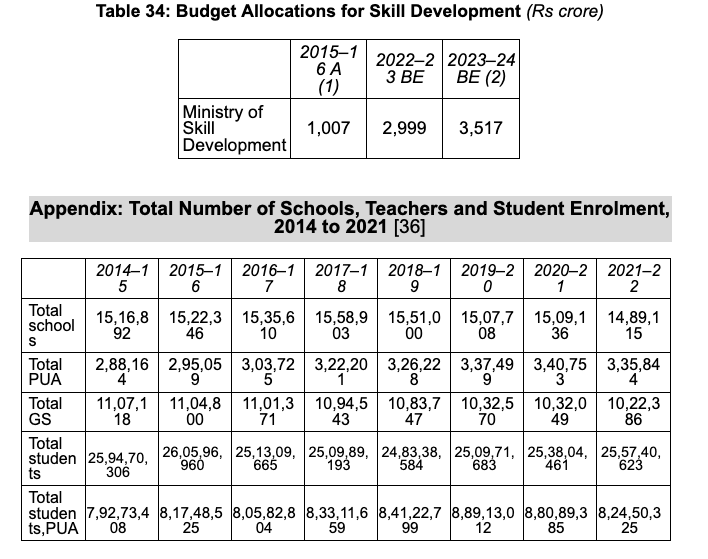

Chart 7: Total Teachers in Government Schools, 2014–2021 (in lakh)[14]

Note 1: Data excludes teachers in government-aided schools;

Note 2: For detailed data, see Appendix.

Worse, a significant number of these teachers are not even professionally qualified. Official data admits that as of 2017–18, nearly 15% of the government teachers (7.3 lakh out of a total of 49.8 lakh), and a huge 27% of the teachers in private unaided schools (8.4 lakh out of 30.6 lakh) are not professionally qualified. (UDISE reports for subsequent years have stopped reporting this data.) [15] These are significantly high numbers. But the NEP does not have any concrete recommendations about training these teachers.

The NEP also does nothing to address the other important issue of weakening of service conditions of teachers and promoting contractualisation. This has been an integral part of the gradual privatisation of the school education system since the 1990s. Official data says that as of 2017–18, 13% government teachers (6.7 lakh) are either on contract or part-time [16]. Without giving job security to teachers, why will the “best and brightest” youth join the teaching profession? Only those who do not get better quality jobs will enter this profession, out of compulsion, and not because they have a passion for teaching. Instead of addressing this issue, the NEP introduces an even more worse ‘tenure track system’ for appointment and confirmation of teachers. In the earlier system, teachers were made permanent after a defined probation period. But this new system will enable the school managements to keep the teachers on a contractual basis for an extended period, with only a promise of confirmation at some future date. They will be forced to serve the bidding of the higher officials and managements. How will this ensure their “respect, dignity, and autonomy”?

NEP in fact further promotes the contractualisation of teachers by advocating recruitment of “local teachers”. But the policy is silent on their service conditions.[17] Given the entire orientation of the Modi Government towards financing school education, this only means that they will also be recruited as contract teachers, and given a fraction of the pay of regular teachers.

NEP 2020 also abolishes reservation in both the recruitment and promotion of teachers and replaces the entire Constitutional provision of Social Justice by the misleading concept of ‘Merit’ which represents the social privileges of the upper classes/castes inherited over generations.[18]

iv. Severe Shortage of Classrooms

NEP-2020 proclaims that the “credibility of Government schools shall be re-established” and for this, “special care shall be taken to ensure that no school remains deficient on infrastructure support”. In reality, except for creating a few ‘schools of excellence’ like PM Shris, the government is starving the remaining 99.5% schools of funds with the result that they suffer from dilapidated buildings, rickety furniture, lack of separate washrooms for girls, absent teachers, some even have no electricity and drinking water facilities. Here are some staggering facts from official DISE data:

- In 2017–18, 55,000 schools (of which 49,000 were primary schools) functioned with just a single classroom (or no classroom). Again, the overwhelming number of these were government schools — 45,800![19]

- 57 percent of all primary schools (all managements) had three or less than three classrooms (data for 2015–16);[20]

- The condition of our schools is so bad that 44% schools did not even have a boundary wall in 2017–18 (no data available for subsequent years).[21]

Combining the above data for inadequate teachers and inadequate classrooms in primary schools leads to the jaw-dropping conclusion that:

- a single teacher is teaching two or three different classes at the same time in a single room in a majority of the primary schools in the country! (The situation is equally bad in the senior-level schools in the country.)

v. High Drop-Out Rate

Therefore, it is not at all surprising that of those who enrol in school in Class-1, a large number don’t complete even elementary education. The drop-out rates at the various levels are:

- Drop-out rate at the elementary level is 21.2% (this means that of 100 children enrolled in Class-1, 78.8 complete Class-8);

- Drop-out rate at the secondary level is 46.6% (this means that of 100 children enrolled in Class-1, only 53.4 complete Class-10).

- Of 100 children enrolled in Class-1, only 41.9 reach Class-11.[22]

vi. Declining Quality of Education

And of those who do complete elementary education, the quality of education imparted is so bad that they can hardly be called educated! The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) is an extensive nationwide citizen-led rural household survey conducted by the NGO Pratham that provides a snapshot of children’s schooling and learning in rural India. Its 2022 report found that:

- 57% children in Class-5 are not able to read Class 2–level text;

- 30% children in Class-8 are not able to read Class 2–level text;

- 55% children in Class 8 cannot solve a simple division problem.

The ASER report also found that learning abilities of children have deteriorated over the past decade. Thus, the proportion of children enrolled in Class-5 who can at least read a Class 2-level text fell from 47% in 2012 to 43% in 2022; and the percentage of children in Class-8 who can do simple division fell from 48% in 2012 to 45% in 2022.[23]

vii. Result: Increasing Privatisation of School Education

All these facts only go to show the Modi Government’s apathy towards improving our public education system. All the tall claims made in NEP-2020 about improving the quality of our public education system to bring all school-age children who have dropped out of school back to school are just empty rhetoric. On the contrary, during the Modi years, the public school education system has suffered an unprecedented decline. The severe deterioration in the quality of government schools has led to children exiting the government school system in droves; those who can afford it have entered private schools; with the result that probably for the first time since independence, total school enrolment (in all schools, government and private) has actually declined! Over the period 2014–15 to 2019–20:

- the total number of students in government schools declined from 14.41 crore ito 12.81 crore, a fall of 1.6 crore (11.1%) in just 5 years;

- while student enrolment in private unaided schools increased by 96 lakh over these five years (from 7.93 crore to 8.89 crore), it was not enough to compensate for the decline in government school enrolment;

- and so total enrolment in all schools (government and private) fell from the peak of 26.06 crore in 2015–16 to 25.1 crore in 2019–20, a decline of 96 lakh (see Chart 8).

After that, the pandemic struck. The Modi Government’s callous handling of the pandemic led to sharp rise in poverty and unemployment in the country, because of which lower-middle class and even some middle class parents found it difficult to send their children to fee-charging private schools, and they shifted their wards from private schools to government schools. Consequently:

- in the two years from 2019–20 to 2021–22, student enrolment in private schools fell by 64.6 lakh (a few thousand private schools even shut down), while student enrolment in government schools increased by 1.24 crore!

Overall, during the Modi years, the degeneration of the public education system has led to lakhs of students being pushed out of the formal education system:

- student enrolment in government schools during the Modi years (2014–15 to 2021–22) has declined by 36 lakh;

- total student enrolment in all schools (government and private) has fallen from the peak reached in 2015–16 of 26.06 crore to 25.57 crore in 2021–22, a decline by 49 lakh (Chart 8).

Chart 8: Student Enrolment in Schools, 2014–2021 (in crore)[24]

Note 1: Total students excludes students in pre-primary; total students includes students in government schools, government-aided schools, private unaided schools and unrecognised schools and other schools; enrolment in government schools does not include students in government-aided schools; enrolment in private unaided schools does not include students in other schools.

Note 2: For detailed data, see Appendix.

The decline in government school enrolment provided the perfect alibi for the Modi Government to shut down government schools. Official data reveals that during the first seven years of the Modi Government (2014–15 to 2021–22) for which data is available:

- thousands of government schools shut down: the total number of government schools fell by 84,700 — from 11.07 lakh in 2014–05 to 10.22 lakh in 2021–22.

- private unaided schools increased by 47,000 over this period;

- the increase in private unaided schools has not been able to compensate for the sharp decline in government schools, because of which the total number of schools has declined by 70,000 (from the peak of 15.59 lakh in 2017–18 to 14.89 lakh in 2021–22) (see Chart 9).

Chart 9: Number of Schools by Management, 2014–2021 (in lakh)[25]

Note 1: Total schools includes government schools, government-aided schools, private unaided schools and unrecognised schools and other schools; government schools does not include government aided schools; private unaided schools does not unrecognised and other schools.

Note 2: For detailed data, see Appendix.

The worst sufferers of this ‘education crisis’ are obviously going to be children from the weakest sections, especially children from Dalit, Adivasi and minority families, and girl children. Of the lakhs of children who are being pushed out of school, they would be constituting the largest section. But the NEP does not have any tangible provisions to address the deep-rooted inequities in Indian society. Though it has an entire section devoted to equity in education, it makes only verbose statements, but there is no mention of the most important provision mentioned in the Indian Constitution to address these historical inequities — reservation. NEP-2020 seeks to repudiate the provision for reservation in admissions, recruitment and promotions given in the Constitution for the historically oppressed sections of society, and replace them by ‘merit’. Not only that, the Modi Government has scrapped several scholarship schemes for school children from scheduled castes and tribes, girls and minorities that encouraged them to complete higher secondary education:

- The Union Government has stopped pre-matric scholarships for students from class 1 to 8 belonging to SC, ST, OBC and minority communities from the academic year 2022–23. The allocation for this scheme, now for only Class 9 and 10 students, is Rs 500 crore. That the government wants to phase out this scheme too, is obvious from the fact that the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment has pointed out that as of 31 December 2022, the government has spent only Rs 56 lakh out of this Rs 500 crore, or a tiny 0.1%.[26]

- The Modi Government has also discontinued the scholarship under the National Scheme for Incentive to Girl Child for Secondary Education — the scheme provided girls belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes who passed Class 8 a scholarship of Rs 3,000 per year to encourage them to pursue education till Class 12. [27]

- Centre has drastically reduced its spending on the post-matric scholarship for Scheduled Caste students — this provided around 60 lakh students a yearly financial assistance of about Rs 18,000 at the higher secondary stage (Classes 11–12) to help them complete their education. After spending Rs 4,010 crore on this scheme in 2020–21 (Actuals), it allocated Rs 3,415 crore in 2021–22 BE, but spent only Rs 1,980 crore (Actuals). In 2022–23, it allocated Rs 5,660 crore in the BE, but the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment has pointed out that as of 31 December 2022, the government has been able to spend only Rs 2,500 crore.[28] This year, it has increased the allocation to Rs 6,360 crore. Considering the spending pattern of the past two years, this increased allocation seems to be more for propaganda purposes.

All this can mean only one thing — that the Modi Government is simply NOT INTERESTED in providing good quality education to all our children. While creating a tiny number of well-funded good quality PM Shri schools — to ‘showcase’ its commitment to providing high quality school education — it is actually seeking to ruin the quality of the remaining, more than 99%, of our public education system, and thus create the grounds for privatisation of school education. Lakhs, even crores, of children are going to be pushed out of government schools, especially children from the most marginalised sections of society — the process has already begun. Those who can afford it will join fee-charging private schools.

The Modi Government has a plan for these drop-outs. Under the cover of a lot of florid jargon, it seeks to corral them into vocational training so that they become ‘cheap trained child labourers’ for corporate houses, enabling the latter to make even more profits. The Modi Government’s NEP-2020 is the first policy since independence to deny formal class room-based education at school level![29]

It is the return of Manuvaad once again. Most of the children denied formal education and pushed into vocational training will be children from the lower castes!

Business of Higher Education

Privatisation of higher education has taken place at a much faster pace than that of school education, because of which more than two-thirds of all higher education institutions in the country are today in the private sector.[30] Private higher educational institutions are for-profit institutions; therefore, very few students can afford their fees.

With the result that barely 20% of children in age group 17–23 are in any kind of higher education degree or diploma course; this proportion is above 60 for developed countries; for many countries, this ratio is above 70.[31]

During the Modi years, privatisation and commercialisation of higher education has accelerated. This is in accordance with the NEP-2020, that makes a big push for privatisation of all public higher education institutions (HEIs) by setting a target of making all HEIs autonomous over a period of 15 years. [32] While the NEP says that this autonomy will be academic and administrative, and the HEIs would be provided adequate financial support, this assurance is only on paper. In reality, the Modi Government is gradually centralising all academic and administrative control over HEIs,[33] and pushing them towards becoming financially autonomous — as we discuss below, it has drastically reduced its funding for ordinary government colleges. Only the more elite institutions can seek to become autonomous — as only they will be able to set up high-fees charging course and attract students from more affluent families to them. The remaining universities and colleges cannot even think of becoming autonomous, as they will go bankrupt. With the government seeking to reduce its educational funding, these remaining public HEIs will be gradually forced to close down.

At the same time, NEP-2020 also encourages the entry of the private sector into higher education, under the guise of permitting entry of ‘philanthropic institutions’ in education (without making any attempt to distinguish between ‘private’ and ‘philanthropic’ institutions). It allows ‘philanthropic institutions’ to make profits (the NEP uses a more mellifluous word for this — ‘surpluses’). It is not that private HEIs were not making profits earlier. But this is the first time since independence that the government is officially allowing private or philanthropic educational institutions to make profits by hiking fees, withdrawal of fee subsidies, reduction in scholarships, salary cuts and dilution of infrastructural facilities. The only restriction is to ‘invest the surplus in education sector’.[34]

NEP completely deregulates fee and salary structures of educational institutions if they merely fulfil the requirement of online transparent self-disclosure. So, it allows loot — only you must be transparent about it![35]

NEP-2020 proposes to establish a National Testing Agency (NTA) to conduct a single entrance examination for all university and college admissions in the country. This will make it difficult for students from weaker sections of society to take admission in HEIs. NEP also proposes to replace the three-year undergraduate degree program with a four-year program — which is also going to adversely affect students from weaker backgrounds as it increases the cost of completing a degree course.

The NEP also has a proposal to provide a lollipop for students not able to complete the extended degree course. It provides for “multiple exit points” in higher education courses — students can exit the 4-year degree course after 1 or 2 or 3 years of education, and they will be given a certificate certifying the number of years they have studied. Given the high unemployment levels in the country, this certificate is going to have little job value.

There is little reason for doubt: the Modi Government is seeking to deny higher education to children from the marginalised sections of society.

With the Modi Government pushing for privatisation of higher education, it is therefore reducing budgetary funding for higher education. In the first 9 Modi budgets (2014 to 2022), Centre’s spending on higher education increased by just 4.4% (CAGR); taking inflation into account, this implies a cut in real terms. In this year’s education budget, the squeeze continues. The higher education budget has increased by 8% over last year’s RE — which means that in real terms, the budget is near-stagnant (see Table 31).

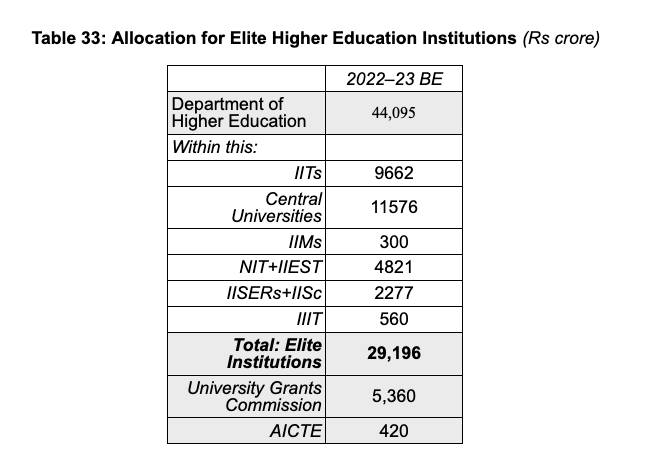

Even within the limited higher education budget, most of the funding is going to elite government institutions like the IITs and IIMS:

- Two-thirds (66%) of the higher education budget has been allocated for the elite higher educational institutions, that is, the IITs, IIMs, IISERs, NITs, IIITs, IISc, and the Central Universities! These together total not more than 100 in number.

- Allocation for the University Grants Commission, that regulates the higher educational institutions in the country and provides grants to around 20,000 colleges and several hundred universities, has been drastically cut in the 10 Modi budgets, from Rs 8,978 crore in 2014–15 BE to just Rs 5,360 crore in 2023–24 BE — a 65% cut in real terms (CAGR, assuming 6% inflation).

- Likewise, allocation for the All India Council for Technical Education, the regulator of engineering education in India, has remained dismally low during all the 10 Modi budgets and is a lowly Rs 420 crore in the 2023–24 BE.

- The Rashtriya Uchhatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA) is the most important Centrally Sponsored Scheme for providing aid to State higher and technical institutions to improve their quality, equity, access, and research. Spending on this important scheme was Rs 1,400 crore in 2016–17. Since then, it has sharply fallen to just Rs 242 crore in 2021–22 Actuals (BE was Rs 3,000 crore) — reflecting the concern of the Modi Government towards improving the quality of our higher educational institutions. Allocation for this scheme was Rs 2,043 crore in last year’s BE; the RE show that spending has come down to just Rs 361 crore. This year’s allocation is a more modest Rs 1,500 crore — let’s see how much is spent.

With such tiny allocations for the UGC, AICTE and RUSA, most government funded colleges are starved of funds and so, to meet their expenses, are being forced to increase student fees using all kinds of excuses. Consequently, studying in government funded educational institutions too is becoming unaffordable for students from poor families.

What we can definitely conclude is: the government is clearly not concerned about improving the overall quality of our higher educational institutions, or providing formal higher education to our children.

Cogs in the Corporate Wheel

The corporate-fascist alliance ruling the country is very clear in its outlook. There is no need to educate the young, especially those from the marginalised sections — only then can they be transformed into mindless automatons in the service of virulent Hindutva. So the overall budget for government colleges where the children of the poor study has been sharply reduced in the ten years of Modi rule.

But the corporates also need good quality engineers and managers. And so, within the reduced budget for higher educational institutions, the spending on elite engineering / management colleges and setting up so-called ‘world class institutions’ has been hugely increased, and constitutes two-thirds of the higher education budget. Private HEIs are also proliferating — which cater exclusively to the children of the rich.

At the same time, the corporates also need skilled workers for their assembly lines. For this, the youth must be trained — not educated — so that they can become cogs in the corporate wheel. The Modi regime has in fact opened a separate ministry for this, the Ministry of Skill Development, and allocation for the most important program under this, the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana, has more than tripled since it was launched eight years ago (Table 34).

Notes

1. World Bank figures: “Government Expenditure on Education, Total (% of GDP) – World”, https://data.worldbank.org; see also: “Public Spending on Education as a Share of GDP”, Our World In Data, https://ourworldindata.org. Similar data is given in a Parliament document: “Background Note on Trend and Pattern of Expenditure on Education and Health”, Research and Information Division, Lok Sabha Secretariat, July 2022, https://parliamentlibraryindia.nic.in.

2. According to one study, per capita spending on elementary education in India was Rs 12,768 in 2011–12 (Ambrish Dongre, Avani Kapur, Vibhu Tewary, “How Much Does India Spend Per Student on Elementary Education?”, Centre for Policy Research, https://accountabilityindia.in.). That year, Government of India (Centre and States combined) spent Rs 277,053 crore on education (data from Economic Survey 2013–14). In 2020–21, this had increased to Rs 575,834 crore (Economic Survey 2022–23). Total student enrolment in government schools in elementary education had declined from 12.94 crore to 10.45 crore over this period (DISE data). Assuming that total expenditure on elementary education has increased in the same proportion as total public expenditure on education, per capita expenditure on education in 2020–21 then works out to Rs 32,861 (roughly $438). In contrast, the average public expenditure on primary education per student in the OECD counties in 2019 was around $10,000. (“Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Indicators”, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org; another article gives an even higher figure: “Annual Expenditure per Student on Educational Institutions in OECD Countries for Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Education in 2019, by Country (in U.S. dollars)”, https://www.statista.com.) 10000/438 = 22.8. The OECD countries public spending on higher education per student as compared to that of India is much higher than this ratio. The OECD countries per capita spending on higher education is around $12,000; on the other hand, except for its spending on a few elite institutions, the General Government expenditure of India on higher education has been sharply falling. So actually the ratio of overall per student public spending on education of developed countries and India is much more than 23.

3. Private recognised unaided schools accounted for 2.5% of total primary schools, 8.4% of upper primary schools, 12.7% of secondary schools and 6% of higher secondary schools. Source: N.V. Varghese and J.B.G. Tilak, The Financing of Education in India, International Institute for Educational Planning, UNESCO, Paris, 1991, http://unesdoc.unesco.org.

4. UDISE Flash Statistics 2017–18, NIEPA, New Delhi, http://udise.in/flash.htm. Apart from private unaided recognised schools, other private schools (include recognised and unrecognised madarsas and other unrecognised institutions) accounted for 2.5% of all schools and 3.2% of total student enrolment.

5. India’s Missing Millions of Out of School Children: A Case of Reality Not Living Up to Estimation? 2 November 2015, https://www.oxfamindia.org.

6. New Education Policy 2020, MHRD, Government of India, p. 61, https://www.education.gov.in.

7. Ibid., p. 5, 10.

8. For more on this, see: Navneet Sharma, “Decoding PM-SHRI”, 16 September 2022, https://www.deccanherald.com.

9. Data for total number of government schools and government school enrolment taken from: “UDISE + Report 2021-22”, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in.

10. New Education Policy 2020, op. cit., p. 4.

11. To be more precise, there are a total of 1,05,102 single teacher schools in the country, of which 80,623 are primary schools. Data taken from: “School Education in India”, UDISE Flash Statistics 2017–18, op. cit.

12. Santosh Kaloji, “Data: There are 1.17 Lakh Single-Teacher Schools Across the Country in 2021–22”, 3 March 2023, https://factly.in.

13. Calculated by us from data given in: Elementary Education in Urban India, Analytical Report, 2015–16 and Elementary Education in Rural India, Analytical Report, 2015–16, NUEPA, New Delhi, available online at: http://schoolreportcards.in.

14. All data from UDISE reports. Data for 2014–15 to 2017–18 from: UDISE Flash Statistics 2017–18, op. cit. Data for subsequent years from: UDISE + Report 2018–19, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in; UDISE + Report 2019–20, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in; UDISE + Report 2020–21, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in; and UDISE + Report 2021–22, https://dashboard.udiseplus.gov.in.

15. UDISE Flash Statistics, 2017–18, ibid. Data for government teachers does not include teachers in government aided schools.

16. Ibid. Data for subsequent years not available. Data does not include teachers in government aided schools.

17. New Education Policy 2020, op. cit., pp. 9, 21.

18. For a more detailed discussion on this, see: “National Education Policy 2020: An Agenda of Exclusion and Enslavement”, AIFRTE document, April 2021, available on the AIFRTE website, “AIFRTE – Democratising Education”, https://aifrte.in. See also: Kumkum Roy, “National Education Policy Needs Close Scrutiny for What it Says, What it Doesn’t”, 31 July 2020, https://indianexpress.com. Following an uproar on this issue after the announcement of the NEP-2020, the Minister for Education stated that the NEP will not dilute provisions of reservation in educational institutions enshrined in the Constitution, but the fact of the matter is that there is no mention of the word “reservation” in the NEP.

19. UDISE Flash Statistics 2017–18, op. cit.

20. Calculated by us from data given in: Elementary Education in Urban India, Analytical Report, 2015–16 and Elementary Education in Rural India, Analytical Report, 2015–16, op. cit.

21. UDISE Flash Statistics 2017–18, op. cit.

22. Calculations done by us, based on data given in: UDISE+ Flash Statistics, 2021–22, op. cit. The methodology adopted by us is: We have taken the annual drop-out rate data for primary level, and used it to calculate the overall drop-out rate for primary education. Then, we have used the Transition Rate data and annual drop-out rate for upper primary level, to calculate the overall elementary level drop-out rate. Using the same methodology, we have calculated the drop-out rates for senior schools.

23. Annual Status of Education Report (Rural) 2022, Provisional, January 2023, https://img.asercentre.org. The figures are weighted average for children in government and private schools.

24. Source for data: Same as Chart 7: All data from UDISE reports.

25. Source for data: ibid.

26. “Only Class 9, 10 Students to be Considered for Pre-Matric Scholarship Scheme”, 1 December 2022, https://indianexpress.com; Jayanth R., “Union Government Stops Pre-Matric Scholarship for SC, ST, OBC and Minority Students of Class 1 to 8”, 29 November 2022, https://www.thehindu.com; Bharat Dogra, “‘Reform’ to Help Dalits Muddled Up: Just 0.1% Disbursal of Pre-Matric Scholarship Funds”, https://www.counterview.net; “Centre Has Spent Only 1% of This Year’s Allocations for Pre-Matric SC Scholarships”, 23 March 2023, https://www.thehindu.com.

27. “Centre Discontinues Incentive Scheme for Girl Students, Plans to Restructure the Scheme”, 27 July 2021, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com; “Union Budget 2022: No Schooling Scheme for Poor Girls”, 2 February 2022, https://www.telegraphindia.com.

28. Bharat Dogra, “‘Reform’ to Help Dalits Muddled Up: Just 0.1% Disbursal of Pre-Matric Scholarship Funds”, https://www.counterview.net; “Centre Has Spent Only 1% of This Year’s Allocations for Pre-Matric SC Scholarships”, 23 March 2023, https://www.thehindu.com.

29. For more on this, see: “National Education Policy 2020: An Agenda of Exclusion and Enslavement”, AIFRTE document, op. cit.

30. “Majority of Indian Colleges are Run by Private Sector, Govt Tells Rajya Sabha”, 29 July 2021, https://www.livemint.com; see also: Neoliberal Fascist Attack on Education, pp. 51–52, Lokayat publication, available on Lokayat website, http://lokayat.org.in.

31. J.B.G. Tilak, How Inclusive Is Higher Education in India? 2015, http://www.educationforallinindia.com; see also: Neoliberal Fascist Attack on Education, Lokayat publication, ibid.

32. This has been repeatedly mentioned in the NEP-2020 policy document: New Education Policy 2020, op. cit., pp. 34-35, 49.

33. For more on this, see: “National Education Policy 2020: An Agenda of Exclusion and Enslavement”, AIFRTE document, op. cit.

34. New Education Policy 2020, op. cit., p. 49.

35. Ibid.

36. Source: Various UDISE reports (see endnote 14).