Kabir Agarwal, Anuj Srivas

How impactful will finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s relief package for India’s poorest actually end up being?

The Narendra Modi government unveiled the contours of the Rs 1.7 lakh crore package on Thursday, with a promise that it was for people who needed immediate help – like migrant workers, and the urban and rural poor.

The headline figure of Rs 1.7 lakh crore may imply that the full amount will be spent immediately or even over the next three months, but this will likely not be the case.

A closer examination of the fine-print shows three major takeaways. Firstly, less than half of the total package, around Rs 60,000 crore, is in the form of cash transfers that will provide immediate help to those that have been affected by the lockdown.

Secondly, it is clear that this package won’t really be stretching the Centre’s fiscal deficit at all, because a few of Sitharaman’s key ‘announcements’ are actually parts of pre-existing government programmes (PM Kisan, MGNREGA) that have already been rolled out and would have been given to the target groups in due course. Or, put more simply, parts of the Rs 1.7 lakh crore package is a repackaging of existing material.

Lastly, a few of the package’s components involve leaning on states to use money they should have already ideally been using (welfare fund for construction workers) or the Centre should have been using (district mineral fund for health policy measures). For both these measures, it is unclear over what time-period these funds will be spent and in what quantity.

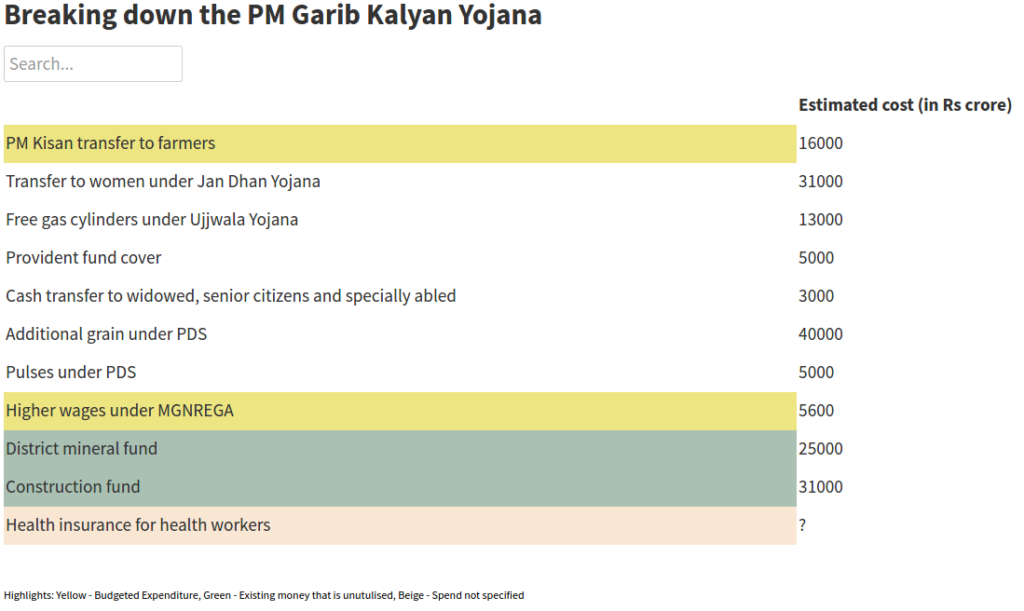

The figures in the table are from the first press release circulated by the government to reporters on March 26.

What the table (shows) is that the Centre will actively spend new and additional (not already budgeted) expenditure only on three major areas. This includes cash transfers to women and elderly, free cylinders under the Ujjwala scheme and increased grains and pulses through PDS. It is unclear at the moment how much the health insurance package that was offered to health workers fighting the COVID-19 pandemic will end up costing.

As experts The Wire spoke to have pointed out, the biggest glaring flaw with Sitharaman’s package is that it still doesn’t provide immediate relief to the millions of migrant workers and daily wage labourers that have been hit hard by the lockdown.

Construction workers left adrift

Beyond this though, there are multiple problems with individual components of the overall scheme.

For instance, while it is great that states and union territories are finally being prodded to use un-utilised welfare funds collected through a mandatory cess under the the Building and Other Construction Workers (BOCW) Act, it is unclear how many construction workers and labourers will be left out of this safety net. So far, around Rs 52,000 crore has been collected as BOCW Welfare Cess, of which around Rs 31,000 crore remains unutilised.

Initial estimates say that anywhere between 30% to 40% of workers may not receive welfare funds through this mechanism. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, while talking to reporters after announcing relief measures on Thursday, said “there are 3.5 crore registered workers.”

However, the Centre’s own official Invest India website puts the total number of workers in the construction sector at 5.1 crore. (Our estimate of the construction sector workers in the informal sector are also around 5.1 crore workers – Editor.)

Jai Kisan?

As part of the financial package, Sitharaman announced that Rs 2,000 crore will be paid under PM Kisan to 8.69 crore farmers ‘immediately’.

However, the CEO of PM Kisan, Vivek Aggarwal told The Wire that he is hopeful that the payment will be made by the end of the first week of April, which is still 10 days away. Several economists have pointed out that at a time like this when lakhs have been rendered jobless overnight and supply chains have been broken down, it is essential to provide financial assistance immediately. The transfer, however, will not be immediate even though the government has registered these farmers and made payments in the past which means that further payments can be made swiftly.

Another aspect of this announcement which is puzzling is that this payment was due even if the pandemic was not upon us and is not a new allocation.

Under the PM Kisan scheme, farmers are due Rs 6,000 annually paid in three equal instalments. The first instalment of the financial year 2020-21 becomes due in April 2020 and has been accounted for in the budget last month.

So, the Rs 2,000 announced by Sitharaman as part of the package would have been due anyway and the money has already been allocated in the budget for this purpose.

Under PM Kisan, the Centre also had the option of providing greater relief at this time as it was not able to spend the entire allocation of 2019-20 and 2018-19. Cumulatively, in those two budgets an allocation of Rs 95,000 crore had been made under PM Kisan. So far, only about Rs 56,000 crore, or 59%, has been spent because bureaucratic inefficiencies have not allowed the programme to scale up. So, almost Rs 40,000 crore that had already been allocated for PM Kisan was not spent. It would have been significant if the PM Kisan payout had been increased this time around as a signal that this government is ready to loosen its purse strings when it comes to farmers.

MGNREGA

Again, the Centre has not made any additional allocation for the MGNREGA scheme. The wage rates are revised every year in April.

As Jean Dreze has pointed out, the wage increase to Rs 202 per day announced by the finance minister is lower than the prevailing MGNREGA wage rates in 29 states. According to a March 23 notification of the government of India, the notified wages under MGNREGA is lower than Rs 202 for only 6 states.

For instance, in Haryana the per day wage under MGNREGA is Rs 309, 52% higher than the wage rate announced by Sitharaman. In Kerala the wage rate is Rs 291.

(In other words, the enhanced MNREGA wage of Rs 202 per day announced by the finance minister is way below the wages that have already been notified. – Editor)

There is also the issue of pending dues of around Rs 1,800 crore under MGNREGA which have not been paid for the 2019-20 financial year. Sitharaman made no reference to this in her press conference, but it appears that it has finally taken a global pandemic for the government to force over what is already due to India’s daily wage labourers. Media reports say that the Centre will release all pending wages under the programme by April 10, which may amount to thousands of crores.

Finally, another question mark over MGNREGA is that given the need for social distancing, will work be generated? Several district magistrates and state governments have disallowed MGNREGA works to continue. In that case no MGNREGA wage will become due and even the regular hike will do no good.

(Kabir Agarwal and Anuj Srivas are reporters with The Wire.)

Editorial addition: In another article, economist Jean Dreze adds:

The Finance Minister has claimed that wage increase under MNREGA will provide an additional Rs 2,000 benefit annually to a worker. This claim asssumes that the said worker gets a full 100 days of MNREGA employment. In reality, only a small minority of MNREGA workers reach this upper limit. So, this claim is only meant to make media headlines. In reality, there is nothing in the package for the MNREGA workers. (Jean Drèze, “Has the Finance Minister Pulled a Fast One on MNREGA Workers?”)