Mögen andere von ihrer Schande sprechen,

ich spreche von der meinen.

[Let others speak of their shame,

I speak of my own.]

– Bertold Brecht, Deutschland, 1933

It’s the early 1970s. An American and a Soviet are debating which of their societies is freer. ‘At least we can criticize Nixon!’, the American blurts out. ‘So what?’, the Soviet replies. ‘We can criticize Nixon too.’ Nixon was, after all, more than worthy of critique: his administration was responsible for perpetuating the worst massacres in Indochina, the extermination of the Black Panthers at home, for backing Pinochet’s bloodstained coup in Chile; the list goes on. But today it appears that the roles have been reversed. When it comes to the war in Ukraine, Westerners find themselves in a situation not unlike that of the Brezhnev-era Soviet. ‘We are free to criticize Putin!’, they exclaim.

To be clear: Vladimir Putin is a true reactionary, with his nostalgia for the Tsars, his Orthodox Christian fervour and ironclad alliance with one of the world’s most objectionable religious hierarchies, his vision of a feudal state-capitalism, the rampant corruption he has enabled and encouraged, his butchery in Chechnya, his repression of dissent. And of course, his suicidal invasion of Ukraine, an anachronistic return to trench warfare in Europe that risks an atomic holocaust over territory – the Donbass – that a decade ago hardly anyone knew existed. To measure the extent of Putin’s folly beyond the horrors he has unleashed, one need only recall that in 2013, 80 per cent of Ukrainians had a positive opinion of Russia.

We would not have been awed by the bravery of Soviets who criticized Nixon’s barbarism – by a commentator in Leningrad describing him as the new Hitler. The same holds true today: unlike Russian citizens who risk their lives in doing so, we should hardly be celebrating the ‘courage’ of pundits in the West who deprecate the cruelty of this Eastern satrap (Oriental despotism: will this rhetorical topos, the coinage of Karl August Wittfogel, ever die?). Not to mention the unpleasant aftertaste of cowardice in the unremitting dictum of ‘we’ll arm you and you fight’ for which they have been a megaphone over the past year and a half. It’s all too easy to play tough with other people’s lives.

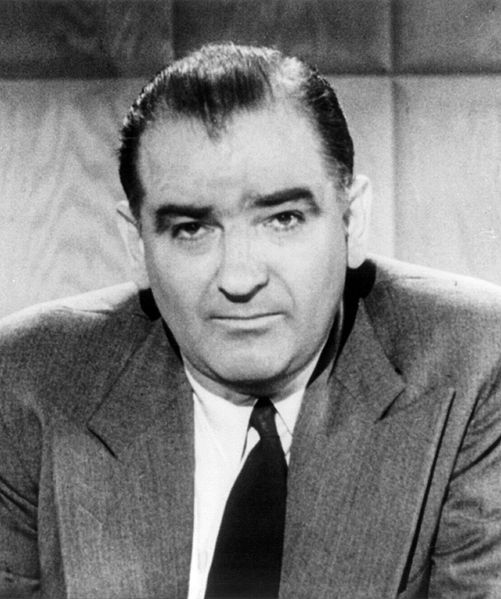

The phenomenon being outlined here echoes the past in some respects, while not abiding by it. The same division of the world into good and evil defined the McCarthyism of the 1950s. For readers who don’t remember, the term derived from American senator Joseph McCarthy, who together with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUCA), led a witch hunt targeting anyone (actors, directors, journalists, musicians, writers, diplomats, even members of the armed forces) suspected of being a communist. It’s no coincidence that Wittfogel himself participated in this witch hunt. In 1951, he accused the UN delegation chief and Canadian diplomat Herbert Norman of being a communist agent. Norman denied everything, but he was once again put under indictment. He committed suicide in Cairo.

There are, of course, significant differences. McCarthyism deprived its targets of their livelihoods in the name of a hunt for spies and traitors. Today’s campaign hasn’t gone as far. McCarthyism infected the American state and media, but since it also attacked them as either soft on communism or harbouring secret communists, an internal opposition grew, and it was ultimately ended by the establishment itself. Currently, what we might call Western Brezhnevism seems to be spreading unopposed. The result is a homogenization of perspective. Rather than la pensée unique, we have a récit unique. What is required of NATO members is unwavering adherence to an orthodoxy, demanding a level of self-censorship that recalls what the atomic physicist Leo Szilard said about Americans during the Cold War: ‘Even when things were at their worst, the majority of Americans were free to say what they thought for the simple reason that they never thought what they were not free to say’.

Here I’m not referring merely to war propaganda, which is a given (and inevitable): our bombs only hit military targets, the enemy’s exclusively civilian ones; our soldiers are gentlemen, theirs are barbarians who commit atrocities; if we lose a city, it was of little strategic importance; if the enemy loses it, it was vital. I’m not even talking about lies, again a given in war; propagated not out of malice, but because you cannot give true information to the enemy. I’m describing something more subtle that permeates our thinking. The clearest signs, as always, come in lexical form. Why, for example, are Russian billionaires called oligarchs, but never Western ones? Billionaires in any nation form – by definition – a small group that exerts great power over the country. But the term oligarch implies something more: that the regime in which they operate is not a true democracy (read: like ours) but an oligarchy. The term is thus a building block for the construction of a non-democratic, authoritarian enemy.

The double standards are more telling in the use of the term ‘empire’. In Russia’s case – whether for Tsarism, the Soviet era, Putin’s revanchism – the term is used constantly, but in the mainstream press it is never applied to the United States, a peace-loving state concerned only with defending itself against ignoble aggressors. That the US has more than 750 military bases in 85 countries is an irrelevant detail (by way of comparison, the UK has 17 military bases abroad, France 12, Turkey 10, China 4, Russia 10, of which 9 are in countries within the borders of the former Soviet Union). Equally irrelevant is the fact that since the Second World War, it has triggered more wars than any other state on earth (in Guatemala, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Nicaragua, Grenada, Panama, Iraq, Serbia, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, Syria…). And that’s not counting the coups d’état staged in Chile, Iran, Cuba…

Then there is the received vocabulary for hired soldiers, by now a resource used by almost all militaries (let’s not forget its august forefather, far less romantic than the stories we have been told, the French Foreign Legion established in 1831). On the American side they are demurely referred to as ‘contractors’, while their Russian counterparts are ‘mercenaries’ (an appropriate term in both cases). Meanwhile the former head of the Wagner Group, the recently deceased Yevgeny Prigozhin, was part of the ‘inner circle’ or ‘clique’ of the Kremlin Tsar, but the head of Blackwater, Erik Prince, is merely a ‘businessman’ who just happens to be the brother of Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s education minister. All such organizations recruit criminal offenders and all commit atrocities, though some are euphemized as ‘unintended casualties’ while others are signs of ‘barbarism’. We need a quantitative analysis of the Western media’s use of adjectives like those carried out by Franco Moretti on literary texts.

Perhaps the most telling indication of this new orthodoxy is the proliferation of the expression ‘Putin’s useful idiots’. A search on Google yields 321,000 results. The history of ‘useful idiots’ – implying as it does a cynical view of politics, in which good faith and naivety are exploited – is enlightening. As William Safire wrote in a New York Times Magazine article from 1987: ‘This seems to be Lenin’s phrase, once applied against liberals, that is being used by anti-Communists against the ideological grandchildren of those liberals, or against anybody insufficiently anti-Communist in the view of the phrase’s user.’ But Safire’s research failed to uncover the expression in any of Lenin’s writings and speeches. The cynicism of the term was thus used against its supposed first formulators.

Use of the expression faded with the end of the Cold War which had spawned it (‘Cold War’ itself a term coined by Walter Lippmann). But in 2008, it was reinvented as ‘Putin’s Useful Idiots’ in Foreign Policy. Paraphrasing Safire: to qualify one merely had to be insufficiently anti-Putin in the eyes of those using the phrase. One should, of course, remember the context. In the early 2000s Putin was asking to become a NATO member (as Foreign Policy reminded its readers last year in the article, ‘When Putin Loved NATO’). But by 2008, things had been turned on their head; the issue was no longer if Russia should be accepted, but how to grant Ukraine and Georgia access to NATO as a move against Russia (this was also the year of the war between Russia and Georgia over South Ossetia and Abkhazia). ‘Putin’s useful idiots’ appeared again in a New York Times article in 2014, the year of Ukrainian President-elect Viktor Yanukovych’s dethroning. Usage has steadily intensified, the floodgates finally opening after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Since then, it’s appeared in headlines (just to give an idea) in the Atlantic, the Spectator, Politico and the Economist.

An example of the term’s noxious application comes from Steve Forbes, editor of the eponymous magazine, who in June 2022 attached the epithet to French president Emmanuel Macron for having the temerity to propose a diplomatic solution to the conflict. The episode recalls when another French president insolently refused to participate in the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Such was George Bush’s anger at Jacques Chirac that his administration tried to convince Americans to change the name of ‘French fries’ to ‘freedom fries’. This was a repeat of the campaign undertaken during the First World War, in a climate of intense Germanophobia, when ‘frankfurters’ were renamed ‘hot dogs’ – considerably more successful than Bush’s feeble rebranding of fried potatoes.

On the long list of Putin’s useful idiots, one name that is conspicuous by its absence is Henry Kissinger, who wrote in an opinion piece in the Washington Post in 2014:

The West must understand that, to Russia, Ukraine can never be just a foreign country. Russian history began in what was called Kievan-Rus. The Russian religion spread from there. Ukraine has been part of Russia for centuries, and their histories were intertwined before then. Some of the most important battles for Russian freedom, starting with the Battle of Poltava in 1709, were fought on Ukrainian soil. The Black Sea Fleet – Russia’s means of projecting power in the Mediterranean – is based by long-term lease in Sevastopol, in Crimea. Even such famed dissidents as Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Joseph Brodsky insisted that Ukraine was an integral part of Russian history and, indeed, of Russia.

He concludes:

Putin should come to realize that, whatever his grievances, a policy of military impositions would produce another Cold War. For its part, the United States needs to avoid treating Russia as an aberrant to be patiently taught rules of conduct established by Washington. Putin is a serious strategist – on the premises of Russian history. Understanding US values and psychology are not his strong suits. Nor has understanding Russian history and psychology been a strong point of US policymakers.

Clearly, Kissinger has the qualifications necessary to be on the list of ‘Putin’s useful idiots’. Why has he not been branded as such? Because it’s hardly credible that the old fox of Realpolitik is an idiot, let alone at the expense of a comparative youngster like Putin. Perhaps he could have been termed a Putinversteher instead (Google yields 41,000 results for it), the German equivalent meaning ‘one who understands Putin’, which replaces the instrumental contempt of ‘useful idiots’ with innuendo: ‘understanding’ hinting at sympathy, support or complicity.

The sleight of hand is not an innocuous one. The war had barely broken out when Repubblica, one of the most important Italian newspapers, published a list of Putinverstehers, an exercise in public derision of prominent journalists and ambassadors for their adherence to the notion – verified a thousand times over throughout history – that the guilt of one party does not imply the innocence of the other. ‘But this is just pro-Putinism in disguise!’, retort commentators who until the day before yesterday hailed Putin as a political heir of Talleyrand and Metternich, ignoring his butchery in Chechnya, not to mention his ridiculous shirtless horseback rides, his photo-ops with tigers, his childish passion for martial arts, his boundless admiration for C-list actors like Jean-Claude Van Damme. How can you attribute intelligence to someone who idolizes Van Damme?

Swiftly, the discourse migrated from Putinversteher to all-out Russophobia. As Mikhail Shishkin argued in the Atlantic:

Culture, too, is a casualty of war. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ukrainian writers called for a boycott of Russian music, films and books. Others have all but accused Russian literature of complicity in the atrocities committed by Russian soldiers. The entire culture, they say, is imperialist, and this military aggression reveals the moral bankruptcy of Russia’s so-called civilization.

That Ukrainians adopt this stance is understandable – à la guerre comme à la guerre – though they might have stopped short of closing the museum in Kiev dedicated to their compatriot Mikhail Bulgakov on account of his opposition to Ukrainian nationalism. Many great Russian authors were Ukrainian: Gogol, Chekhov (born near Mariupol), Akhmatova (born in Odessa)… But the fact they were born in Ukraine doesn’t mean they felt Ukrainian, just as writing in Russian doesn’t make you Russian, just as Austrian or Swiss authors would never feel German for writing in German, and Americans wouldn’t want to be called English just for writing in it. I have great admiration for the novel The Penguin, written by Andrei Kurkov, a Ukrainian author who writes in Russian but champions the Ukrainian cause. All this underlines the speciousness of Herder’s triad: ein Volk, eine Sprache, ein Land.

Denigration of all things Russian can be observed everywhere. Register the sudden absence of Russian films from our cinemas, even those of esteemed directors like Andrey Zvyagintsev, winner of several prizes at Cannes and a Golden Globe. The classics of world literature have not been spared either. See, inter alia, ‘From Pushkin to Putin: Russian Literature’s Imperial Ideology’, published in Foreign Policy, which characterized both Tolstoy and Pushkin as Russian imperialists (even if the latter’s reconstruction of the Pugachev Rebellion seemingly demonstrates his sympathies for the insurgency). Since the war began, several monuments to Pushkin in Ukraine have been demolished (and yet we express indignation when the Taliban destroys statues of Buddha?), and as the Financial Times reports, ‘some Ukrainians now refer on social media to “Pushkinists” launching missile attacks on their cities’.

No artist has suffered this vilification more than Dostoevsky. The equation is linear: Dostoevsky fashioned himself as the standard-bearer of the so-called ‘Russian soul’ (Russkaia Dusha) which ‘embodies the idea of pan-humanistic unity of brotherly love’. The Russian soul is at the heart of the idea that Russia must unify all of the Slavic people within and beyond its borders, and therefore the theoretical foundation for Russian imperialism of which Putin is an expression. Ergo, Dostoevsky is the inspiration for Putin, just as Nietzsche was for Hitler. For more than a century, Dostoevsky – along with Tolstoy – was considered a literary giant alongside Dante, Cervantes, Shakespeare and Goethe. Suddenly he’s a reprobate.

The analogy between Dostoevsky–Putin and Nietzsche–Hitler brings us to a final discursive aspect of this new orthodoxy: the constant comparison to Hitler and Stalin, which in modern secular theology means only one thing – identifying the person one speaks of as Satan. It is not the first time we have seen this film: figures whom only yesterday world powers had treated as trusted friends are suddenly declared monsters, madmen, criminals. An expedient amnesia is employed, alongside a moral rigour worthy of Cato the Younger. No need to go back to the praise that the Anglo-Saxon press bestowed on Mussolini (Hitler received the same treatment for a while too); one has merely to remember how Saddam Hussein was financed and armed to fight against Iran, only to become a criminal, and then a condemned man after an abominable farce of a trial. The same happened with Bashar al-Assad. In short, as soon as a crony ceases being a crony, he becomes a criminal (not that he wasn’t one before, but our eyes were closed then). Roosevelt’s immortal reply to those who pointed out that Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza was a son of a bitch applies in every case: ‘Yes, but he’s our son of a bitch’.

Putin stopped being our son of a bitch some time ago now. But that doesn’t automatically make him a new Hitler. His was a violence of an almost metaphysical ferocity, so terrifying, so apocalyptic, that it doesn’t compare to that of the little despots who are often likened to him. To put Hitler side by side with any old murderer is akin to comparing every neighbourhood massacre to the Shoah. It ultimately diminishes the enormity of the Judeocide, a step towards absolving its perpetrators.

One last consideration: you know you’re in trouble when the political class starts to talk about the defence of values. As Carl Schmitt observed, values are an intrinsically polemogenous category, that is to say, one that generates conflict. In order to value, one must devalue other values – defeat them and subordinate them, thereby exercising tyrannical power. If patriotism is the last refuge of scoundrels, values are more like the first resort of tyrannical powers: it is no coincidence that fascism championed ‘the ethical state’. There is no possible compromise in the defence of values; only crusades can be fought in their name. This is especially true when we’re dealing with an idea as vague and ill-defined as ‘Western values’. What are these: slavery, practised for centuries? Wars to force a country to import opium? Concentration camps in which to cage asylum seekers, the billions handed to tyrants to keep them out, the patrolling of the seas to make them drown in the tens of thousands?

Western values seem to function intermittently, like a car’s indicator lights. For Kosovo, the idea that a linguistic and ethnic minority has the right to secession and independence holds. But not for the Donbass. For Ukraine, the right to resist invasion and occupation is sacrosanct. But not for the Palestinians. The truth is that in the game of the great powers, the issue is not really the territorial integrity of Ukraine. This is a mere pretext for the ‘defence of values’, for their export in fact. Better still if they’re exported by means of cluster bombs banned by a UN convention signed by 111 states (but not the US, Russia, Ukraine, China, India, Israel, Pakistan and Brazil). Cluster bombs render Western values all the more convincing.

(Marco d’Eramo is an Italian journalist and social theorist. Courtesy: Sidecar, the blog of New Left Review. The New Left Review is a British bimonthly journal covering world politics, economy, and culture, which was established in 1960.)