Matthew Ehret

In Africa, injustice looms large, marked by poverty, warfare, and famine. Despite post-WWII political gains, economic independence, a vital component of true freedom as envisioned by Pan African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Patrice Lumumba, and Haile Selassie, remains elusive.

After decades of restrictive IMF and World Bank loans, poverty, hunger, and conflict persist throughout the continent. While many attribute this to Africa’s governance challenges, in reality, a deliberate imperial agenda has hindered the continent’s development in all political, economic, and security sectors.

Coups against neo-colonialism

But much has changed in the past few years. The growing clout of Eurasian institutions that fully embrace Global South countries as valuable, integral, and equal members – the BRICS+ and Greater Eurasian Partnership are examples – offer hope that old neo-colonial shackles will be broken and that Africa can enjoy an unfettered renaissance.

The rise of a new global pole to challenge the old unipolar order has had a notable impact across sub-Saharan West Africa which, in recent years, has seen a surge in military coups shifting power away from regimes that had long prioritized the interests of western corporations.

These coups occurred in Chad (April 2021), Mali (May 2021), Guinea (September 2021), Sudan (October 2021), Burkina Faso (January 2022), Niger (July 2023), and Gabon (August 2023) – all resource-rich countries with abnormally poor living conditions.

In Gabon, over 30 percent of its people live on less than $1 per day, while 60 percent of its regions have no healthcare or clean drinking water despite the abundance of gold, diamonds, manganese, uranium, iron ore, natural gas, and oil – mostly monopolized by French corporations like Eramat, Total and Ariva.

Despite its abundance of rare earths, copper, uranium, and Gold, 70 percent of Malians still live in abject poverty. SImilarly, Sudan, with its riches in oil, fertile soil, and water, has 77 percent of the population living below the poverty line.

In uranium-rich Niger, which provides over 35 percent of the fuel for France’s nuclear industry (accounting for 70 percent of France’s energy basket), mainly under the control of France’s Orano, only 3 percent of Nigerians have access to electricity. In the “former” French colony of Chad, that number is only a little higher at 9 percent, and a still-unacceptable 20 percent in Burkina Faso.

While Altanticists desperately seek ways to keep their talons embedded into the African continent and its abundant riches, a much healthier security paradigm has emerged in recent years from Eurasia.

A new security paradigm for Africa and the world

Since the 2021 coup in Mali, Russian military support has skyrocketed, with the supply of numerous fighter jets and Turkish drones, accompanied by Russian military advisors who have provided substantial assistance to the state.

This approach mirrors Moscow’s strategy in other conflict-ridden countries, such as Syria, where the focus is on eradicating terrorism and supporting legitimate governments.

In 2022, following local accusations that French troops were supporting the Al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorists they claimed to be fighting, 400 Russian military personnel were deployed to Boko Haram-infested Mali. This move marked a significant shift in the region’s security dynamics.

Despite the extensive presence of US and French military bases across Africa and the substantial financial investments in “counter-terrorism” efforts on the continent, militant violence has continued to escalate dramatically, with sub-Saharan Africa witnessing an 8 percent increase in terrorism over the previous year.

Last year, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 60 percent of all terror-related deaths. A 2021 African Center for Strategic Studies report shows that 18,000 conflicts affected sub-Saharan states resulting in over 32 million displaced persons and refugees.

Map of African countries generating the largest share of forced displacement

Russia has steadily established itself as a dependable supporter of African national governments in recent years, by leveraging its advanced defense industry and military intelligence capabilities. It aims to foster cooperation and development alongside China and the broader BRICS+ group, thereby creating a more conducive environment for mutual growth.

While the west portrays Russia as weak and isolated, the fact that 49 African nations were present at the second Africa-Russia Summit in July 2023 paints a very different picture.

Russia has also emerged as Africa’s top arms supplier – representing 44 percent of arms imports from 2017-2022 – and has signed military/technical agreements with 40 African states. Moreover, Moscow has engaged in joint military training exercises with countries like Egypt, Algeria, South Africa (in collaboration with China), and Tunisia.

Map of African states which have military cooperation with Russia

Alternative to rules-based order

During the May 2023 11th International Meeting of High Representatives for Security Issues, Russian President Vladimir Putin reaffirmed the objectives of his country’s vision, stating that nations should jointly work towards “strengthening stability in the world, the consistent construction of a system of unified indivisible security, solving major desks of ensuring economic, technological and social development”.

The Russian leader called out the need to create a “more just multipolar world, and that the ideology of exclusivity, as well as the neo-colonial system, which made it possible to exploit the resources of the world, will inevitably become a thing of the past.”

From 28 August to 2 September, 50 African Defense chiefs and 100 senior representatives of the African Union attended the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum where the theme was “Implementing the Global Security Initiative and Strengthening Africa-China Solidarity and Cooperation” as an alternative to the rules based order.

Map of African states which have military-technical cooperation with Russia

Chinese military expert Song Zhongping was quoted by Global Times as saying:

“China will not interfere in the internal affairs of African countries, but we will assist African nations in building defensive military capabilities, and we are also willing to enhance collaboration with African countries on counter-terrorism and other non-traditional security matters.”

Sustainable security means economic development

The fight against the destructive effects of imperialism may seem daunting, especially when viewed solely through the lens of military affairs. But the growing influence of major multipolar institutions offers an important, consensus-based, strength-in-numbers way forward.

The BRICS+, for instance, has made sure to add new members strategically. Last month, the organization grew from five to 11 members, which today include three geostrategic African nations of Egypt, South Africa, and Ethiopia, and major West Asian energy powerhouses Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE with extensive interests across Africa.

Then there’s China’s Global Security Initiative, unveiled in April 2022, which represents far more than just a non-western security doctrine. It embodies a fundamentally different paradigm, which at its core, places paramount emphasis on economic development as the foundation for long-term strategic peace.

Beijing has not only endorsed the objectives of the African Union’s Africa Agenda 2063 in words, but has done more than any other country in realizing those ambitious goals which call for “unity, self-determination, freedom, progress and collective prosperity pursued under Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance”.

Over the past decade, China has advanced a policy of rail development, connectivity and building up industrial capacities, training, and skill building across partner nations. During that time, trade with Africa has risen to $282 billion in trade in 2022, marking an 11 percent increase over the previous year—a figure more than four times that of the US, which recorded $63 billion in trade with Africa in 2022.

During that same 10-year span, Chinese companies have won $700 billion in contracted projects to build energy systems, transportation grids, manufacturing hubs, ports, telecommunication, aerospace, aviation, finance, and a myriad of soft infrastructure.

Despite the challenges posed by western interventions, China has been able to build 6000 kilometers of rail, 6000 kilometers of roads, 20 ports, 80 large power facilities, 130 hospitals, and 170 schools on the continent.

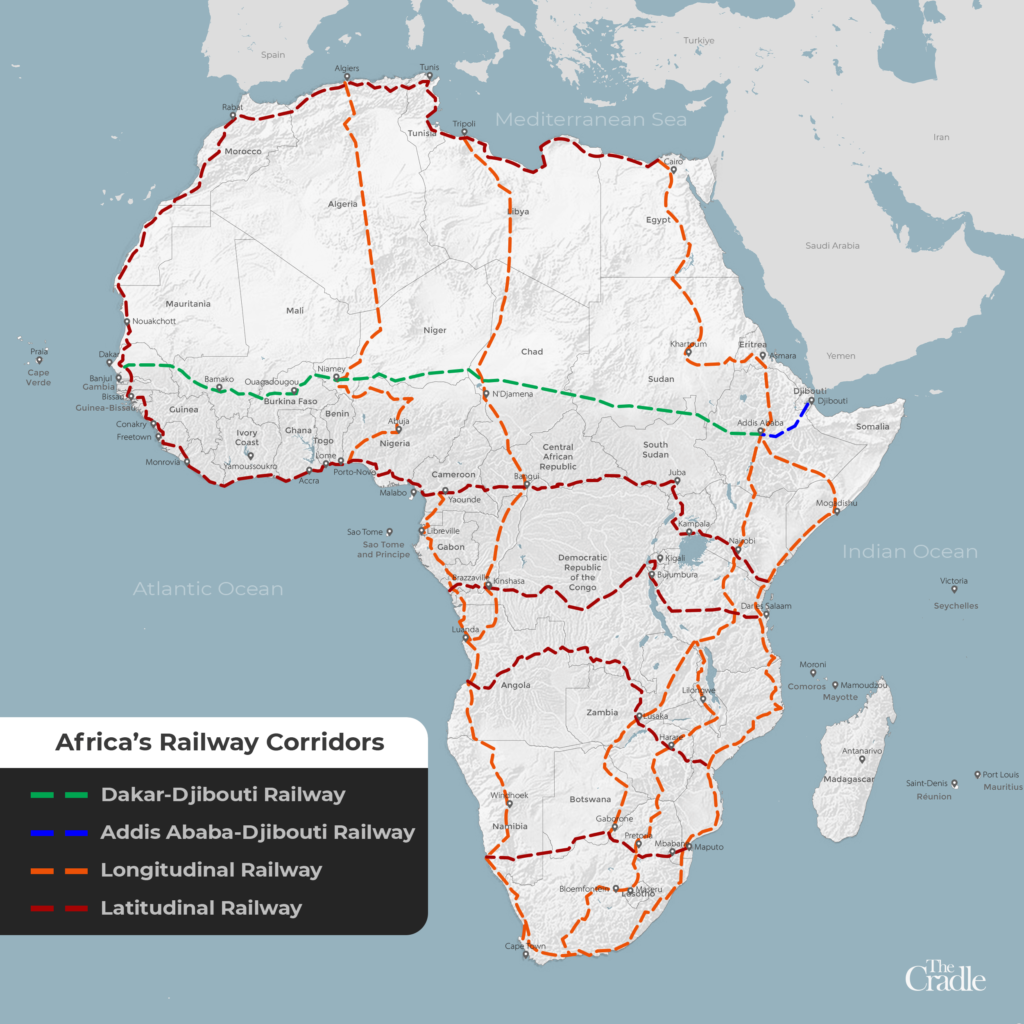

Map of Africa’s railway corridors

western “democracies” resort to the threat of military intervention, punitive sanctions, or assassinations in post-coup Niger, China assumed the role of peace broker and re-emphasized its commitment to continue all projects in Niger, including the crucial 2,000-kilometer pipeline designed to export crude oil from the Agadem fields to the Port of Seme in Benin.

This pipeline, currently three-quarters finished, will boost Niger’s oil output by 450 percent upon completion.

In Tanzania, the Chinese government hosted the 25 August China-Africa Vision conference promoting a myriad of economic initiatives, but its highlight was the Tanzania-Burundi-Democratic Republic of Congo railway which will likely become the first of several major trans continental rail lines outlined in the Africa Agenda 2063 Report.

Another significant development is the construction of northern sections of east-west continental railways. The electrified Djibouti-Addis Ababa railway, completed in 2018, serves as the cornerstone of a major rail corridor connecting Senegal, Mali, Niger, Chad, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Cameroon, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, facilitating trade and economic growth across the sub-Sahara.

The extension of the Trans-African rail across the 29 km Bab el-Mandeb Strait, linking Djibouti to Yemen, and its subsequent connection to the Persian Gulf-Red Sea high-speed rail line currently under construction is indeed an exciting prospect. China’s ongoing efforts in this regard are laying the foundation for broad continental harmony.

China is constructing the “African BRI” (Belt and Road Initiative) in sections, including a 1,228 km line connecting Dakar in Senegal to Bamako in Mali, and a 283 km line connecting landlocked Niger to Nigeria, which is in its final phase of construction.

As this project continues to expand, feeder lines into other landlocked African countries and ports along the Atlantic coast will likely become evident, enhancing connectivity and trade across the continent.

In August, Kenya and Uganda announced the launch of a $6 billion Standard Gauge rail line as part of the Northern Corridor Integration Project of the East African nations extending the already existent Mombassa-Nairobi-Naivasha line built by China in 2018 to Kampala in Uganda, Kigali in Rwanda and then South Sudan and Ethiopia. It will eventually connect with the emerging Djibouti-Dakar railway, further integrating East and West Africa.

North-South African development

In North Africa, three north-south rail lines outlined in the Africa Agenda 2063 Vision have strategic ports in Algeria, Egypt, and Morocco to facilitate trade with Europe. Egypt’s imminent entry into BRICS+ in January 2024, and Algeria’s potential future inclusion, signify the growing geopolitical significance of North Africa as a hub of industrial growth and a gateway between Africa, Europe, and the Eurasian Heartland.

Egypt is Africa’s second largest economy with a $475 billion GDP enjoying a strategic gateway into the Heartland and Europe via both land and sea routes. China is also helping to build Egypt’s high speed rail system alongside German firms and is a major investor in Egyptian ports – Alexandria, Abu Qir and El Dekheila – that are integrated with the supply lines into Europe where China has a controlling stake in Greece’s Port of Piraeus.

Morocco, which successfully built Africa’s first high speed railway (Al Boraq) with financing from France, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait, has also built the Mediterranean’s largest port – the Tanger Med Port – with China financing 40 percent of the port’s expansion. This advanced transportation grid has inspired European automakers like Groupe Renault and Groupe PSA to launch factories in the region.

While China has not built automotive facilities in Morocco, it has built a massive $400 million aluminum casting plant which supplies material used by French automotive producer Peugeot, and although China failed to win the contracts to build the first phase of Morocco’s high speed network, plans are in motion to take the lead on the upcoming extensions.

From the standpoint of energy geopolitics, Russia’s Rosneft owns a stake in Egypt’s Zohr offshore natural gas field and in June 2022 Russia’s Rosatom began building a third generation reactor set to begin generating energy in 2026 located in El Dabaa. Russia also has a $2.3 billion stake in a petrochemical complex and oil refinery in Morocco and Rosatom is carrying out studies for Moroccan desalination plants.

Africa is undeniably on the move, and the quest for economic independence, long denied by colonial powers, is finally emerging. The rise of a multipolar order, with ancient civilizational states cooperating and adhering to Natural Law, offers hope for the eventual post-Hobbesian order, bringing us closer to a more just and harmonious world.

(Matthew Ehret is a journalist, lecturer and founder of the Canadian Patriot Review. Courtesy: The Cradle, an online news magazine covering the geopolitics of West Asia from within the region.)