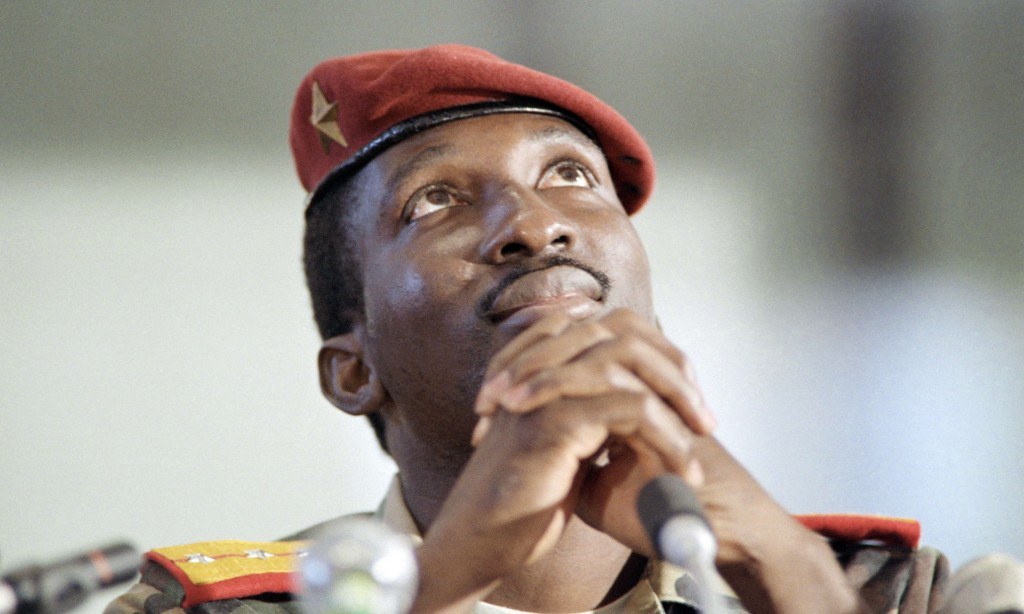

Thomas Sankara Remains a Global Icon

Owen Schalk

“We encourage aid that aids us in doing away with aid,” asserted Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso from 1983 to 1987. “But in general welfare and aid policies have only ended up disorganizing us, thus beguiling us and robbing us of a sense of responsibility for our own economic, political and cultural affairs.”

In order to restore that sense of responsibility, Sankara implemented a socialist, anti-imperialist agenda aimed at cultivating a self-sufficient economy run by the Burkinabè people, for the Burkinabè people. His agenda included, among other things, refusal to pay Burkina Faso’s debts to Western-run institutions on the grounds that, one, it was illegitimately accrued, and two, constant debt serving was anathema to African development.

As ideologically void military coups rock Burkina Faso and the debt crisis across the African continent grows more urgent by the year, the Burkinabè people are readying to commemorate Sankara on the thirty-fifth anniversary of his assassination. Sankara’s four years in power proved that alternative development models that do not subscribe to the imported precepts of neocolonial institutions are not only possible, but necessary if underdeveloped nations want to develop in endogenous and sustainable ways.

When Sankara seized power in 1983, his government represented a radical break from the past. Named “Upper Volta” by the French and underdeveloped in a classic colonial fashion, formal independence brought little material change to the country. A series of puppet rulers kept the country in France’s neocolonial dominion, while the majority of Upper Volta’s population remained undereducated and undernourished. When Sankara, a military captain who espoused the tenets of Marxism-Leninism, took power in a coup, continent-wide hopes for African socialism were reinvigorated. The Zanzibarian socialist A.M. Babu summed up the hopeful feeling:

Captain Thomas Sankara… can be instrumental in reviving that post-colonial enthusiasm which most people had hoped would be rekindled by [Mugabe’s] Zimbabwe but was not; the enthusiasm that cleared bushes, built thousands of miles of modern roads, that dug canals on the basis of free labour and the spirit of nation-building.

A man of informal style and modest values, Sankara nevertheless espoused an ambitious development program for the African continent. Firstly, he renamed his country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso—“the land of upright people”—and nationalized the majority of its resources, most importantly the farmland and mineral reserves. He launched a series of “commando” operations to build a nation-spanning railroad (the people constructed almost 100 kilometres of railway in two years), increase literacy in the countryside (tens of thousands were taught to read), and vaccinate children against measles, meningitis, and yellow fever (two million children were vaccinated in two weeks, saving 18,000 to 50,000 kids who usually died in the yearly epidemics). All these initiatives were undertaken without accepting funds from international financial institutions or encouraging foreign investment.

“We don’t want anything from anyone,” said Foreign Minister Basile Guissou. “No one will come to develop Burkina Faso in place of its own people.” At a time when Africa’s debt was around $200 billion and 40 percent of the continent’s export earnings were going toward debt payments, this was a brave stance to take. Sankara went one step further when, in 1987, he urged the rest of Africa to reject its foreign debt and follow Burkina Faso’s successful model of self-sufficiency.

Sankara’s goal was to ensure the population’s access to food and clean drinking water, a basic but demanding ambition on a continent where hunger and thirst were enforced on whole peoples through the financial institutions and foreign policy agendas of the “civilized” Western world. “Our economic ambition,” he said, “is to use the strength of the people of Burkina Faso to provide, for all, two meals a day and drinking water.”

His policies bore fruit. Between 1983 and 1986, cereal production rose 75 percent and the new Ministry of Water helped many communities dig wells and water reservoirs. Journalist Ernest Harsch recalls: “Ordinary Burkinabè seemed to readily embrace Sankara’s approach, as they mobilized in their local communities to quickly build new schools, health clinics, and other facilities that had once seemed but a remote fantasy.”

Sankara’s independent development policies, combined with a non-aligned foreign policy that saw him enjoy good relations with Cuba, Libya, and the Soviet Union, led the Europeans (and particularly the French) to turn against the revolutionary government. Much like other revolutionary processes in Cuba and Venezuela, Sankara’s government was successfully implementing a new development strategy that spurned the racist paternalism and interventionist austerity of Western financial institutions in favour of a model of self-sufficiency rooted in popular mobilization. Moreover, Sankara demanded respect from the Global North, and especially from Burkina Faso’s former colonizer. “What is essential,” he stated, “is to develop a relationship of equals, mutually beneficial, without paternalism on one side or an inferiority complex on the other.”

The French government’s attitude toward Sankara grew increasingly negative during his time in power. For example, during a brief border war between Mali and Burkina Faso in 1985, France sold weapons to Mali. Overall, Sankara had deprived France of influence in West Africa, and the success of his alternative path portended an even greater diminishment of French influence as other peoples in the region would likely realize that self-sufficiency was possible. As such, the French retained close ties with conservative governments in neighbouring Togo and Côte d’Ivoire, especially the Ivorian president Félix Houphouët-Boigny, whose country was home to many Burkinabè exiles who opposed the Burkinabè revolution.

When Sankara traveled to Côte d’Ivoire in May 1984, he was initially banned from visiting Abidjan, the largest city, because Ivorian authorities were worried he would be welcomed more enthusiastically than the country’s own president.

Everything fell apart on October 15, 1987, when former Sankara compatriot Blaise Compaoré launched a coup of his own. His soldiers murdered Sankara and his closest allies and unceremoniously buried their bodies in a mass grave. Harsch reported that, when word of Sankara’s death spread, mourners flocked to the mound to lay flowers and weep.

Compaoré ruled until 2014. Some of his earliest actions included reversing the state monopoly on the mining industry and allowing the International Monetary Fund and the World to return to the country. “Without shame, we must appeal to private investors,” he announced in a clear break from Sankara. “We need to develop capitalism… We have never considered socialism.”

In further contrast to his predecessor, Compaoré built an opulent presidential palace and purchased a luxury jet once owned by Michael Jackson. The West’s immediate embrace of Compaoré and the new leader’s closeness to France (and particularly French ally Félix Houphouët-Boigny) have fed theories that the coup was launched at the behest of Burkina Faso’s former colonizer. To this day, the French government refuses to open its archives on Sankara.

By the late 1990s, foreign exploration teams had discovered huge gold reserves in Burkina Faso. Canada, with its growing investments in gold, was especially interested. By 2003, the following Canadian companies were exploring or developing mines in Burkina Faso: Axmin, Orezone Resources, Etruscan Resources, St. Jude Resources, SEMAFO, and High River Gold. Within fewer than twenty years, Canadian interests would own the majority of gold operations in the country, dominating Burkina Faso’s most profitable export.

In 2014, a popular uprising overthrew Compaoré, bringing an end to decades of openly neocolonial rule. However, the political process that followed failed to break with the past as Sankara would have advised. Canadian pressure was instrumental in preventing substantial reform. As Business Monitor Online explained, “Burkina Faso is heavily dependent on foreign aid, much of it from Canada, the home jurisdiction of most of the miners that would be hurt by significant review.” Former Prime Minister Stephen Harper further protected Canadian investments by finalizing a Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPA), negotiated with the Compaoré regime, while the unelected transition government was in power.

A 2015 meeting between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and former President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré revealed the continuing prevalence of Canadian capital in the country today. As Canadian mining investments in Burkina Faso and all West Africa continued to rise, Kaboré shook hands with Trudeau and “underscored the importance of Canadian investments to Burkina Faso’s economy.”

This year, Burkina Faso has been the site of two military coups. The first, on January 24, overthrew Kaboré and brought officer Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba to power, and the second, on September 30, dislodged Damiba and elevated officer Ibrahim Traore to the head of the military regime. Neither of these coups impacted Canadian investment in the country. An October 3 article in Canadian Mining Journal notes that operations owned by Canada’s Endeavor Mining and IAMGOLD “have not been affected by spreading social unrest following an internal coup d’état.”

Sankara’s vision of an independent, socialist, pan-Africanist model of development—one in which wealth produced in Africa remains in Africa to develop the majority of the population—was not buried with him. He remains an inspiring symbol for people in Africa and beyond. In a recent interview with Democracy Now!, Aziz Fall, coordinator for the International Campaign Justice for Sankara, explained that Sankara “symbolized for most African youths the hope of a sovereign Africa. He actually gave his life for that… And so he’s an icon, I think.”

(Owen Schalk is a writer based in Winnipeg. He is primarily interested in applying theories of imperialism, neocolonialism, and underdevelopment to global capitalism and Canada’s role therein. Courtesy: Canadian Dimension, a forum for debate on important issues facing the Canadian Left today, and a source for analysis of national and regional politics, labour, economics, world affairs and art.)

Speech: ‘Imperialism Is the Arsonist of Our Forests and Savannas’

Thomas Sankara

[Thomas Sankara’s speech,“Imperialism is the arsonist of our forests and savannas,” has resurfaced on the interwebs of late, and with good reason. Apocalyptic, mercurial, and cruelly deadly weather patterns, brought on by the ceaseless malignancy of capitalism and the tireless expansion of imperialism, has produced a planet that is literally on fire, pushing its life forms to the edge of extinction. From Lahaina to Lytton, entire communities have been incinerated, unprecedented wildfires rage from North Africa to Nunavut, and everywhere temperatures rise while air quality declines. Meanwhile, official, governmental efforts to reverse global warming have been half-hearted, hamfisted, or simply non-existent. And in some cases, such as the push for a so-called green-economy, they have merely gussied up old extractive practices with new but empty language. Green capitalism is still capitalism and still based on white imperialism.

Sankara, on the other hand, recognized that the problem of ecological destruction was rooted in capitalism and imperialism. This was the lesson of the experience of the Burkinabe people; this was the vision of the future of the world from the edge of the Sahel, where deforestation and industrial growth had led to the acceleration of desertification and death—and where the solution lay not only in replanting trees, but in revolution. From the perspective of the present, Sankara’s speech is almost visionary. We hope his prophecy doesn’t come to us too late.

Sankara’s “Imperialism is the arsonist of our forests and savannas” was delivered at the First International Silva Conference on Trees and Forests [1ère Conférence internationale sur l’arbre et la forêt] on February 5, 1986 at the Sorbonne, Paris. It was published in the February 14, 1986, issue of the ‘Ouagadougou journal Carrefour africain’ and included in translated form in ‘Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution 1983-1987’. It was recently published by ‘Black Agenda Report’. We reprint it below.]

● ● ●

My Homeland, Burkina Faso, is without question one of the rare countries on this planet justified in calling itself and viewing itself as a distillation of all the natural evils from which mankind still suffers at the end of this twentieth century.

Eight million Burkinabè have painfully internalized this reality for twenty-three years. They have watched their mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons die, with hunger, famine, disease, and ignorance decimating them by the hundreds. With tears in their eyes, they have watched ponds and rivers dry up. Since 1973 they have seen the environment deteriorate, trees die, and the desert invade with giant strides. It is estimated that the desert in the Sahel advances at the rate of seven kilometers per year.

Only by looking at these realities can one understand and accept the legitimate revolt that was born, that matured over a long period of time, and that finally erupted in an organized way the night of August 4, 1983, in the form of a democratic and popular revolution in Burkina Faso.

Here I am merely the humble spokesperson of a people who, having passively watched their natural environment die, refuse to watch themselves die. Since August 4, 1983, water, trees, and lives, if not by survival itself, have been fundamental and sacred elements in all actions taken by the National Council of the Revolution, which leads Burkina Faso.

In this regard, I am also compelled to pay tribute to the French people, to their government, and in particular to their president, Mr. François Mitterrand , for this initiative, which expresses the political genius and clear-sightedness of a people always open to the world and sensitive to its misery. Burkina Faso, situated in the heart of the Sahel, will always fully appreciate initiatives that are in perfect harmony with the most vital concerns of its people. The country will be present at them whenever it is necessary, in contrast to useless pleasure trips.

For nearly three years now, my people, the Burkinabè people, have been fighting a battle against the encroachment of the desert. So it was their duty to be here on this platform to talk about their experience, and also to benefit from the experience of other people from around the world. For nearly three years in Burkina Faso, every happy event, marriages, baptisms, award presentations, and visits by prominent individuals and others, is celebrated with a tree-planting ceremony.

To greet the new year 1986, all the schoolchildren and students of our capital, Ouagadougou, built more than 3,500 improved cookstoves with their own hands, offering them to their mothers. This was in addition to the 80,000 cookstoves made by the women themselves over the course of two years. This was their contribution to the national effort to reduce the consumption of firewood and to protect trees and life.

The ability to buy or simply rent one of the hundreds of the public dwellings built since August 4, 1983, is strictly conditional on the beneficiary promising to plant a minimum number of trees and to nurture them like the apple of his eye. Those who received these dwellings but were mindless of their commitment have already been evicted, thanks to the vigilance of our Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, committees that poisonous touches take pleasure in systematically and unilaterally denigrating.

After having vaccinated throughout the national territory, 2.5 million children between the ages of nine months and fourteen years, children from Burkina Faso and from neighboring countries, against measles, meningitis, and yellow fever; after having sunk more than 150 wells assuring drinking water to the 20 or so districts in our capital that lacked this vital necessity until now; after having raised the literacy rate from 12 to 22 percent in two years, the Burkinabè people victoriously continue their struggle for a green Burkina.

Ten million trees were planted under the auspices of a fifteen-month People’s Development Program, our first venture while awaiting the five-year plan. In the villages and in the developed River valleys, families must each plant one hundred trees per year.

The cutting and selling of firewood has been completely reorganized and is now strictly regulated. These measures range from the requirement to hold a lumber merchant’s card, through respecting the zones designated for wood cutting, to the requirement to ensure reforestation of deforestation areas. Today every Burkinabè town and village owns a wood grove, thus reviving an ancestral tradition.

Thanks to the effort to make the popular masses aware of their responsibilities, our urban centers are free of the plague of roaming livestock. In our countryside, our efforts focus on settling livestock in one place as a means of promoting intensive stockbreeding in order to fight against unrestrained nomadism.

All criminal acts of arson by those who burn the forest are subject to trial and sanctioning by the Popular Courts of Conciliation in the villages. The requirement of planting a certain number of trees is one of the sanctions issued by these courts.

From February 10 to March 20, more than 35,000 peasants, officials of the cooperative village groups, will take intensive, basic courses on the subjects of economic management and environmental organization and maintenance.

Since January 15 a vast operation called the “Popular Harvest of Forest Seeds” has been under way in Burkina for the purpose of supplying the 7,000 village nurseries. We sum up all of these activities under the label “the three battles.”

Ladies and gentlemen:

My intention is not to heap unrestrained and inordinate praise on the modest revolutionary experience of my people with regard to the defense of the Trees and Forests. My intention is to speak as explicitly as possible about the profound changes occurring in the relationship between men and trees in Burkina Faso. My intention is to bear witness as accurately as possible to the birth and development of a deep and sincere love between Burkinabè men and trees in my Homeland.

In doing this, we believe we are applying our theoretical conceptions on this, based on the specific ways and means of our Sahel reality, in the search for solutions to present and future dangers attacking trees all over the planet.

Our efforts and those of the entire community gathered here, your cumulative experience and ours, will surely guarantee us victory after victory in the struggle to save our trees, our environment, and, in short, our lives.

Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen:

I come to you in the hope that you are taking up a battle from which we cannot be absent, we who are attacked daily and who are waiting for the miracle of greenery to rise up from the courage to say what must be said. I have come to join with you in deploring the harshness of nature. But I have also come to denounce the ones whose selfishness is the source of his fellow man’s misfortune. Colonial plunder has decimated our forests without the slightest thought of replenishing them for our tomorrow’s.

The unpunished disruption of the biosphere by savage and murderous forays on the land and in the air continues. One cannot say too much about the extent to which all these machines that spew fumes spread carnage. Those who have the technological means to find the culprits have no interest in doing so, and those who have an interest in doing so lack the technological means. They have only their intuition and their innermost conviction.

We are not against progress, but we do not want progress that is anarchic and criminally neglects the rights of others. We therefore wish to affirm that the battle against the encroachment of the desert is a battle to establish a balance between man, nature, and society. As such it is a political battle above all, and not an act of fate.

The creation of a Ministry of Water as a complement to the Ministry of the Environment and Tourism in my country demonstrates our desire to clearly formulate the problems in order to be able to resolve them. We must fight to find the financial means to exploit our existing water resources, drilling operations, reservoirs, and dams. This is the place to denounce the one sided contracts and draconian conditions imposed by banks and other financial institutions that doom our projects in this field. It is these prohibitive conditions that lead to our country’s traumatizing debt and eliminate any meaningful maneuvering room.

Neither fallacious Malthusian arguments, and I assert that Africa remains an underpopulated continent, nor the vacation resorts pompously and demagogically christened “reforestation operations” provide an answer. We and our misery are spurned like bald and mangy dogs whose lamentations and cries disturb the peace and quiet of the manufacturers and merchants of misery.

That is why Burkina has proposed and continues to propose that at least 1 percent of the colossal sums of money sacrificed to the search for cohabitation with other stars and planets be used, by way of compensation, to finance projects to save trees and lives. We have not abandoned hope that a dialog with the Martians might lead to the re-conquest of Eden. But in the meantime, earthlings that we are, we also gave the right to reject a choice limited simply to the alternatives of hell or purgatory.

Explained in this way, our struggle for the trees and Forests is first and foremost a democratic and popular struggle. Because a handful of forestry engineers and experts getting themselves all worked up in a sterile and costly manner will never accomplish anything! Nor can the worked-up consciences of a multitude of forums and institutions, sincere and praiseworthy they may be, make the Sahel green again, when we lack the funds to drill wells for drinking water a hundred meters deep, while money abounds to build oil wells three thousand meters deep!

As Karl Marx said, those who live in a palace do not think about the same things, nor in the same way, as those who live in a hut. This struggle to defend the trees and Forests is above all a struggle against imperialism. Because imperialism is the arsonist setting fire to our forests and savannas.

Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen:

We rely on these revolutionary principles of struggle so that the green of abundance, joy, and happiness may take its rightful place. We believe in the power of the Revolution to stop the death of our Faso and usher in a bright future for it.

Yes, the problem posed by the trees and Forests is exclusively the problem of balance and harmony between the individual, society, and nature. This fight can be waged. We must not retreat in face of the immensity of the task. We must not turn away from the suffering of others, for the spread of the desert no longer knows any borders.

We can win this struggle if we choose to be architects and simply not bees.[1] The bee and the architect, yes! If the author of these lines will allow me, I will extend this twofold analogy to a threefold one: the bee, the architect, and the revolutionary architect.

Homeland or death, we will win!

Thank you.

(Courtesy: Black Agenda Report, a US publication that gives news and analysis from the perspective of the black left.)