At March on Washington’s 60th Anniversary, Leaders Seek Energy of Original Movement

Aaron Morrison

Sixty years ago, Andrew Young and his staff had just emerged from an exhausting campaign against racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. But they didn’t feel no ways tired, as the Black spiritual says. The foot soldiers were on a “freedom high,” Young recalls.

“They wanted to keep on marching, they wanted to march from Birmingham to Washington,” he said. And march they did, in the nation’s capital. Just four months later, they massed for what is still considered one of the greatest and most consequential racial justice demonstrations in U.S. history.

The nonviolent protest, which attracted as many as 250,000 to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, helped till the ground for passage of federal civil rights and voting rights legislation in the next few years.

But in the decades that followed, the rights gains feeding the freedom high felt by Young and others came under increasing threat. A close adviser to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Young went on to become a congressman, a U.N. ambassador, and Atlanta’s mayor. He sees clear progress from the time when Black Americans largely had no guarantee of equal rights under the law. But he hasn’t ignored the setbacks.

“We take two steps forward, and they make us take one step back,” Young said in an interview at the offices of his Atlanta-based foundation. “It’s a slow process that depends on the politics of the nation.”

At 91 years old, an undeterred Young will gather again with Black civil rights leaders and a multiracial, interfaith coalition of allies on Saturday, to mark 60 years since the first March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, an event most widely remembered for King’s “I Have A Dream” speech.

But organizers of this year’s commemoration don’t see this as an occasion for kumbaya—not in the face of eroded voting rights nationwide, after the recent striking down of affirmative action in college admissions and abortion rights by the Supreme Court, and amid growing threats of political violence and hatred against people of color, Jews, and the LGBTQ community.

The issues today appear eerily similar to the issues in 1963. The undercurrent of it all is that Black people are still the economically poorest in American society. Organizers intend to remind the nation that the original march wasn’t just about dreaming of a country that lived up to its promises of equality and liberty to pursue happiness. They wanted legislative action then, and they want the same now.

The survival of American democracy depends on it, the organizers say. “It’s inevitable to me that this nation, as Martin Luther King said, will live out, one day, the true meaning of its creed,” Young declared.

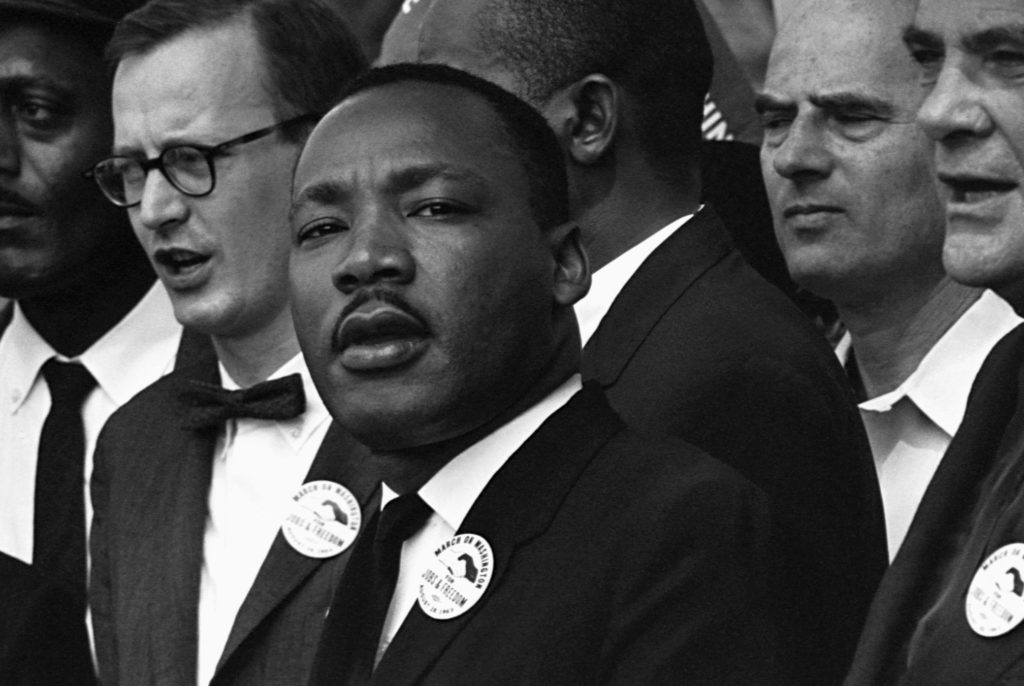

Six decades ago, from the steps of the monument to President Abraham Lincoln, King began his most famous speech by decrying economic disparity, quality of life issues, police brutality, and voter disenfranchisement. He brought his remarks home with the sermonic delivery of his dream of social and class harmony transcending racial and ethnic lines in America.

His words have resounded through decades of push and pull toward progress in civil and human rights. Today, the March on Washington is a marker by which racial progress is measured. But drivers of that progress—namely the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965—have teetered precariously on the edges of partisanship.

“(King) said in the speech, ’We come to here, Mr. Lincoln, because 100 years ago, in 1863, you promised that we’d be full citizens, and America has not fulfilled the promise’,” said the Rev. Al Sharpton, president of the National Action Network and co-convener of the 60th commemoration of the march.

King also said America had given Black Americans a check for equality that had been marked “insufficient funds” in the bank of justice.

“They came (to Washington) in ’63 to say the check bounced,” Sharpton said. “We come in ’23 … to say the check didn’t bounce this time. They put a stop payment on the check. And we’re coming to say, ‘You’re going to take stop payment off the check, and you will pay your debt.’”

This is at least the third time that Sharpton has organized a commemoration of the March on Washington. There was a march in 2000, the 37th anniversary of King’s speech, focused on police brutality and racial profiling. Thirteen years later, the late Rep. John Lewis, who at the time was the last living speaker from the original march, and a host of celebrities, athletes, and politicians attended the 50th anniversary commemoration.

Each time, Sharpton has partnered with members of King’s family. Martin Luther King III, the eldest son of the late civil rights icon, and his wife, Arndrea Waters King, head the Drum Major Institute and are co-conveners of this year’s march. A list of march partners includes about 100 other civil rights, labor, faith, and cultural organizations.

Sharpton’s organization expects tens of thousands to attend on Saturday.

Part of the success of the original march was its turnout, said author Michael Long, who next month will publish the book Bayard Rustin: A Legacy of Protest and Politics, which celebrates the march’s chief architect.

“Rustin really believed that the power on that day would be in numbers created by this coalition that he put together of Black civil rights activists, people from faith communities, and progressive workers in the labor rights movement,” Long said. “Civil disobedience attracts the hardcore few,” he added, “but when you get 250,000 people together on the National Mall, you serve notice on the political leaders of the day.”

Most Americans say King has had a positive impact on the U.S., according to a Pew Research Center report detailing the results of an opinion survey conducted in the spring. Just over half of Americans say there has been a great deal or a fair amount of progress on racial equality since the original March on Washington.

Along racial lines, a clear majority of Black adults (83%) say efforts to ensure equality for all, regardless of race and ethnicity, haven’t gone far enough. About 58% of Hispanic adults, 55% of Asian American adults, and 44% of white adults say the same. A 2022 poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found similar gaps in opinions about the treatment of Black people by police and in the criminal justice system.

Further, in the Pew report, a majority of people who think efforts to ensure equality haven’t gone far enough also feel it is unlikely that there will be racial equality in their lifetime. It’s difficult to blame those with a pessimistic view of racial progress, considering most of the key measures of socioeconomics in America.

Today, Black Americans are more educated, they are less disproportionately incarcerated, and they are in more positions of power than they were 60 years ago. But the Black-white wealth gap is larger now than in 1963, the Black homeownership rate has risen only modestly, and younger Black Americans are more often saddled with student loan debts that dim gains made in other areas. Black Americans and other non-whites live disproportionately in communities plagued by climate disasters and exposure to pollution that shortens their lifespans and depresses their property values.

From neighborhood redlining and job discrimination to healthcare disparities and incarceration, racism has proven to be the most effective tool to uphold an unjust capitalist system, said Jennifer Jones Austin, CEO of the Federation of Protestant Welfare Agencies, an anti-poverty policy and advocacy group and a march partner.

The federation recently released an analysis of stalled civil rights progress in the 60 years since the March on Washington, as a way to re-center King’s focus on economic issues. Job attainment, income inequality, and poverty continue to greatly impact how differently Black Americans and other people of color experience life in the U.S. compared to many white people.

“If America is able to tell the story today, that Black unemployment has reached record lows, but they’re not saying that Black Americans are still disproportionately earning just minimum wage or that they’re not earning as much as their white counterparts, with the same levels of education and experience, they’re only telling half the story,” said Jones Austin who, with the National Action Network and the Drum Major Institute, is lobbying the federal government to change how economic deprivation and need are measured in the U.S.

Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton was a 26-year-old Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee worker in Mississippi in 1963 when she became part of the staff that organized the March on Washington.

“I was on the staff in New York and was the last person to leave because we were getting people on the buses,” she said. “And as I flew from New York to Washington, I could see that the march would be a success because as far as the eye could see, there were crowds. We weren’t sure how big because there had never been such a large march before, but it was overwhelming.”

Norton, now 86, and Washington, D.C.’s non-voting delegate, said she knew once she saw how many people had come that “the march was not only successful, but they would help us with what we wanted the march to do.” The civil rights and voting rights legislation, as well as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, all came in part from the energy and commitment from the march, she said.

Now, 60 years out, she said the political environment is so polarized it is hard to imagine the legislative achievements in the aftermath of the 1963 march being possible now. “Unlike the kind of atmosphere we had during the March on Washington, we have exactly the opposite now,” Norton said.

Indeed, Congress and the White House have often been consistently at odds on modern civil rights and voting rights legislation. A Democratic-controlled House, for example, has passed versions of the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act—it would have restored a potent tool against voting law bias that was gutted by the Supreme Court in 2013—only for a past Republican-controlled Senate and then a narrowly Democratic Senate to block or fall short of sending legislation to the president’s desk.

That’s also been true of police reform legislation proposed after the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis and during unprecedented racial justice demonstrations nationwide. The Floyd legislation was before Congress when Sharpton convened a march at the Lincoln Memorial in 2020 that featured several families of Black victims of police brutality.

Voting rights and police reform aren’t the only issues that march partners want to uplift on Saturday. Increased antisemitic hate crimes, as well as attacks on Asian American communities, have drawn in participation from a range of other groups.

Young, the King adviser and former U.S. ambassador to the U.N., said he thinks it unwise for him to predict how successful this year’s March on Washington will be. But his faith tells him to not place limits on what is possible.

“If there is a place where we can learn to live together as brothers and sisters, rather than perish together as fools, it’s the United States of America,” he said.

(Aaron Morrison is National Race and Ethnicity Writer for Associated Press. Courtesy: People’s World, a voice for progressive change and socialism in the United States. It provides news and analysis of, by, and for the labor and democratic movements.)

60 Years After the March on Washington, Black Economic Inequality Persists

Chuck Collins

Black Americans have endured the unendurable for too long. Sixty years after the famed March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., gave his landmark “I Have a Dream” speech, African Americans are on a path where it will take 500 more years to reach economic equality.

A new report, Still A Dream, coauthored by Institute for Policy Studies and the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, examines the economic indicators since 1963. Our country has taken significant steps towards racial equity since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s. But growing income and wealth inequality over the last four decades has supercharged historic racial wealth disparities, slowing and even reversing many of those gains.

Sixty years without substantially narrowing the Black-white wealth divide is a policy failure. But just as federal policy helped create the racial wealth gap, it can also help close it. In this report, we look in detail at the state of that divide and recommend policy reforms that would substantially narrow it within one to two generations.

A summary of the report follows.

Key Findings

In a few areas, African Americans have made substantial socioeconomic advancements since the 1960s.

- In 1963, Black Americans had a stunningly high poverty rate of 51 percent, compared to 15 percent for white Americans. By 2021, poverty rates had declined, with white poverty at 8 percent and Black poverty at 20 percent. Though this is a substantial decline, it still means almost one in 12 white Americans are in poverty and one in five Black Americans live in poverty.

- The rate of Black high school attainment has sharply increased over the past 60 years, from 24.8 percent in 1962 to 90.1 percent in 2022. But while the college attainment advantage for whites in 2022 (1.7 times that of Black Americans) was substantially lower than it was in 1962 (2.4 times), there is still a substantial divide between Black college attainment (27.6 percent) and white college attainment (37.9 percent).

- Unemployment has been historically low for African Americans over the last few years. Between 1974 and 1994, Black unemployment consistently remained in the double digits, with rates twice as high as those for white Americans. From 1994 to 2017, Black unemployment rates varied between 7 percent and 10 percent, occasionally spiking to nearly 17 percent during recessions. However, since 2018, Black unemployment has reached record lows of 5 percent and 6 percent, except during the 18-month recession caused by COVID-19.

Yet there has been minimal progress in most socioeconomic indicators. At this pace, it would still take centuries for African Americans to reach parity with white Americans.

- For every dollar of white family income, African Americans had 58 cents in 1967. In 2021 African Americans had 62 cents to the white household’s dollar. At this rate, it would take Black households 513 years to reach income parity with white households.

- Median household income for African Americans has grown just 0.36 percent since the turn of the century and it is still lower today than the white median family income in 1963.

- In 1962, African Americans had 12 cents for every dollar of wealth of non-Black Americans. By 2019, African Americans had 18 cents for every dollar of wealth of non-Black Americans. At this rate it would take 780 years for Black wealth to equal non-Black wealth.

- Black homeownership increased from 38 percent in 1960 to 44 percent in 2021, an increase of 6 percentage points. White homeownership has increased from 64 percent in 1960 to 74 percent in 2021, a 10 percentage point increase. In over 60 years, there has not been a bridging of the Black-white homeownership divide.

Solutions and Interventions

“Depressed living standards for Negroes are not simply the consequences of neglect. Nor can they be explained by the myth of the Negro’s innate incapacities, or by the more sophisticated rationalization of his acquired infirmities. They are a structural part of the economic system in the United States.”

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1968

There are a wide range of solutions necessary to narrow the racial economic divide. The five that we believe would make the most difference are:

- A push for full employment and guaranteed jobs.

- A massive land and homeownership program.

- A commitment to individual asset building.

- Policies to reduce dynastic concentrations of wealth and power.

- Targeted reparations and universal health care.

(Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies, where he also co-edits Inequality.org. Courtesy: CounterPunch.)