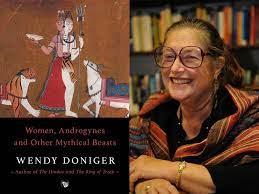

[Wendy Doniger’s Women, Androgynes and Other Mythical Beasts explores gender and sexual identities in Hindu, Buddhist, and Tantric mythologies. It takes us from the union of ‘mother earth’ and ‘father sky’ in the Rig Veda to Shiva’s burning of Kama, the god of desire. The author explores the complex portrayal of dominant women and goddesses in Hindu mythology.

The book delves into the dichotomy between the non-maternal and maternal goddess, the inequality of power structures, and the emergence of a new Goddess in medieval India. The worshiper’s relationship with the Goddess, her ambivalence, and the longing for her presence shed light on the multifaceted nature of devotion in Hinduism.

In this conversation with Githa Hariharan, Wendy Doniger talks about the book and more.]

Githa Hariharan (GH): Who is a saint in the Hindu context? I suspect this question may require a timeline, and address multiple meanings. But the question also gains resonance because of the times we live in – with the full range of ‘saints’, ‘sants’ and ‘godmen’ in the news every day in India, involved in a range of secular / political activities.

Wendy Doniger (WD): The Hinduism I know best and write about, Epic and Puranic Hinduism, the myths and rituals from the ancient and early medieval period, doesn’t have what Christians and even some Buddhists (under, I think, Christian influence) would call ‘saints’: human beings of ordinary birth who take on, either in childhood or later in life, extraordinary religious qualities and powers. What Hindus have, instead, are ordinary human beings who demonstrate extraordinary powers and are then revealed to be incarnate gods or humans possessed or transformed by gods. These gifted individuals actually bear little resemblance to the so-called saints in the Indian newspapers today.

GH: I found the section on ‘the dangers of upward mobility’ (including the title), a powerful indication of how central hierarchy is to organizing all the worlds – of mortals, gods, and anything in between. ‘Knowing your place’ seems to operate even when it comes to earning spiritual points. Would you say there is a glass ceiling in place limiting how far a person can go toward achieving sainthood or god/demigod status through penance and prayer? You mention some cautionary tales about those who aspire to spiritual activities above their station? And would you tie this up with the ‘challenge to brahmin monopoly of spiritual power’?

WD: You are certainly right in everything you say about these deeply embedded hierarchies. But here I think we need to distinguish between two very different powerful and ancient and deeply opposed lines of thinking about apparent upward mobility in the Hindu tradition. On the one hand, in most of the classical Sanskrit texts (the ones I mostly write about), texts composed by brahmins, upward mobility is absolutely forbidden, and there are thousands of cautionary tales about non-brahmins who tried in vain to change their caste and class status and were thwarted and subjected to horrendous punishments, on earth and in the hereafter (whatever the text in question regards as the hereafter).

On the other hand, in later texts from the medieval bhakti period, both in Sanskrit and in vernacular texts, we encounter the phenomenon that my old teacher Mircea Eliade once characterized as ‘briser le toit,’ or ‘break open the roof.’ In these texts, people of low caste, even those we now call dalits, and even women(!), perform actions of great self-sacrifice and generosity and are rewarded, by the god or goddess or gods, by translation to heaven or into the world beyond all heavens, or even, in a few texts, transformation into Brahmins in their later rebirths. These mythical stories reflect great social changes that were going on in India at the time, not in Hindu society as a whole, which remained, and remains, staunchly casteist, but in certain large sections of Hindu society, not just in the breakaway groups of followers of gurus or companies of renouncers and holy men (some of whom were influenced by Sufis), but in the minds of a number of Hindus who remained within the bounds of caste society while at the same time beginning to entertain far more liberal ideas about upward mobility.

GH: How different or difficult is it for a woman to aspire to sainthood? Would this be a far greater challenge to the hierarchical (and brahminical) order of things? I want to link this up with your very powerful statement in another context, “In Indian mythology, the female is truly deadlier than the male.”

WD: Here again we must distinguish between the earlier Sanskrit texts and later texts in Sanskrit and the vernaculars. The earlier texts are spectacularly sexist, rife with stories that prove how wicked, over-sexed, and cunning women are, how they must be ‘guarded’ or ‘protected’ or ‘controlled’ (the fact that one verb, raksh, means all of these things is in itself an indication of the attitude to women in Sanskrit texts) or else they will betray and destroy their husbands. This is what I meant by the ‘deadlier than the male’ remark.

Yet, even in Sanskrit texts, there are some good women (Gargi in the Upanishads, Sita in the Ramayana – alongside the devious and destructive Kaikeyi) who manage to prove their virtue even within the strict bounds of the hierarchy, who make extraordinary sacrifices to save their husbands and/or children, or even sometimes remain celibate and sacrifice themselves for others, and are translated to heaven as a reward. But only in later bhakti texts, particularly in vernacular traditions in Bengali and Tamil and Telugu and so forth, do a few extraordinary women become religious celibates or even religious leaders on a level with male gurus.

GH: In the same vein, I want to ask you about ‘promoting’ an angry woman to the status of a goddess to placate her, but also to pull her back into the sanctioned order of things. I am thinking, of course, of Kannagi in the Silappadikaram, burning Madurai with her plucked out breast. How is the fire, her anger, to be put out? By making her the goddess of chastity? And this seems to me a cunning choice. Am I right in assuming that her wild anger that has been unleashed by the king’s injustice will now be subject, not only to an alliance with the ‘establishment’, but also to the rules of ‘chaste behaviour’?

WD: Yes, the tale of Kannagi is a strange and compelling story. Historians of religion have contrasted goddesses of the breast and goddesses of the tooth (the latter sometimes a euphemism for the yoni, particularly the so-called vagina dentata, the yoni with teeth). Goddesses of the breast are gentle and chaste and nurturing; goddesses of the tooth ambiguous and sexy and dangerous. This is a useful paradigm as far as it goes, though a bit too pat and blatant to serve all circumstances. By tearing off her breast, Kannagi transforms herself from the benign goddess (who makes extraordinary self-sacrifices in her attempt to save her husband) to the fiery, dangerous goddess (to whom others must offer bloody sacrifice if they want to survive). And yes, the way to control a dangerous goddess (think of Kali and Durga) is to worship her, which does not so much tame her as it channels her useful destructive powers into the service of the worshipper – in the case of Kannagi, the service of the king and his armies. And, indeed, as long as she remains celibate, we don’t have to worry about her violent sexuality, do we? The king can channel it into a political weapon, and we can ask her to use it to protect us from our enemies.

GH: Would you comment on how a balance is achieved between acknowledging the potential of women – perhaps vested in that third breast – and anxiety about keeping women, mortal or goddess, in control of men, male gods, and brahminical orthodoxy?

WD: The trouble with acknowledging the powers of women is that it tends to terrify men and drive them to institute extraordinary measures to keep women from using those powers against men. This is the message of so much of classical Hindu mythology. And it still holds true today. As women in India become better educated and more often able to choose their own husbands, or opt not to marry at all, male terror increases and results in the sexual violence and other forms of violence against women that plague India today. The solution is not, however, to backslide and give back those new powers, but to use the increasing literacy of women, and their growing presence in Indian politics, to legislate and enforce measures to channel the power represented by the goddess into political weapons that women can use in legislature and the political presence to protect and empower women.

GH: In particular, how is the anxiety around worship of the ‘demonic goddess’ handled? Whether Sitala and Manasa (or Kali?), the goddess must evoke considerable ambivalence in the devotee.

WD: Yes, goddesses, especially but not only ‘demonic’ goddesses, can be very scary. That’s why we worship them; if we did not, who knows how they might destroy us? But there are just as many ‘breast’ goddesses as ‘tooth’ goddesses. My favourite is Shashti, the goddess of ‘the Sixth,’ that is, the sixth day after childbirth; she is the one who watches over new mothers during this most dangerous period for the survival of the infant. Kali asks you to sacrifice a goat so that you yourself do not become the goat whom she devours, but Shashti and the many other gentle goddesses, breast goddesses, ask only for your prayers and a bit of ghee or a few flowers, in return for which they will stand by your side in time of need. I think women in India, who face very serious problems, should probably invoke both Kali and Shashti to make sure that they cover all the bases in their fight to win equality and, indeed, safety in India today.

(Githa Hariharan is an Indian writer based in New Delhi. Courtesy: India Cultural Forum, a group of cultural activists and academics, who see India as part of a rich and plural heritage, and seek to build on this heritage for a more just, egalitarian and humane society.)