[May 27 is the death anniversay of Jawaharlal Nehru. This article is being published courtesy The Wire.]

India was in my blood and there was much in her that instinctively thrilled me. And yet I approached her almost as an alien critic, full of dislike for the present as well as for many of the relics of the past that I saw. To some extent I came to her via the West, and looked at her as a friendly Westerner might have done. I was eager and anxious to change her outlook and appearance and give her the garb of modernity. And yet doubts arose within me. Did I know India?

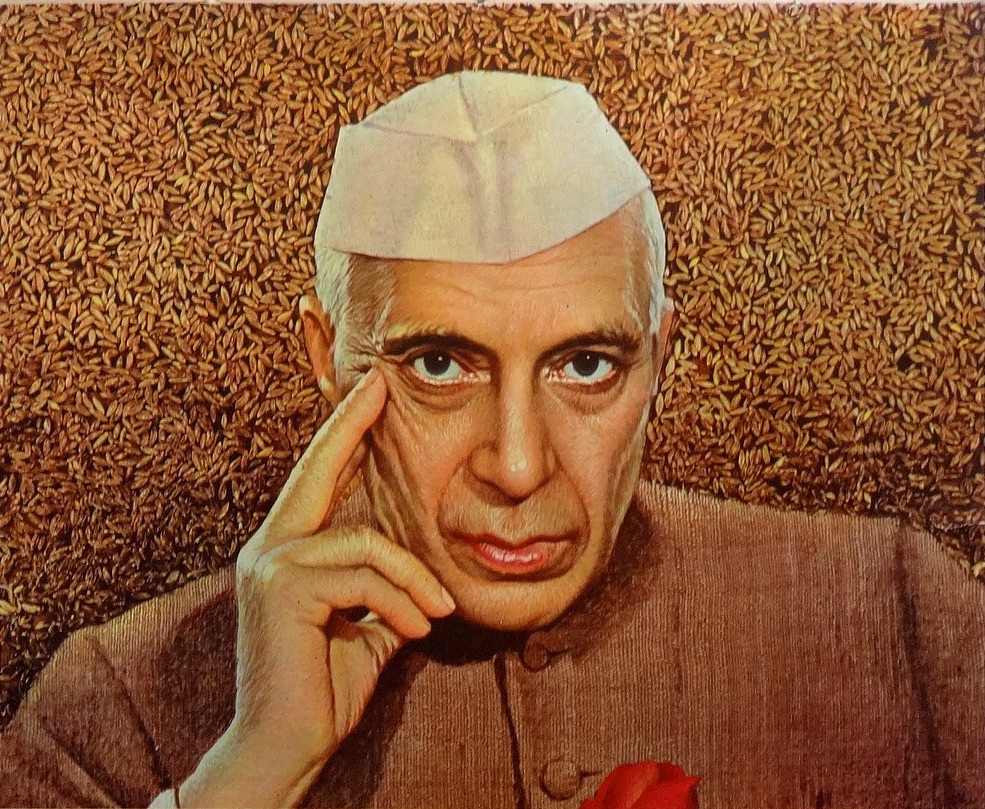

Jawaharlal Nehru, The Discovery of India

May 27, 1964: I was a student of Class II, and my father told me about the demise of Jawaharlal Nehru. It was a small sleepy town in West Bengal, and even as a small child I could feel the moment of mourning and sadness all around. However, everything moves, and with the passage of clock time I too grew up, and experienced many political/historical transformations.

The grandness of Nehru—say, the visual depiction of Nehru with Nasser and Tito generating the spirit of non-alignment; or Nehru with a red rose pinned close to his heart hoisting the national flag as my early memory of calendar art—did remain in my consciousness. But then, after the brief tenure of Lal Bahadur Shastri, we saw the arrival of a major symbol of power, the charismatic Indira Gandhi reminding me of the brilliant letters her father wrote to her, her golden moments during the Bangladesh liberation movement, and eventually the manifestation of her authoritarianism causing the toughness of Emergency and simultaneous growth of the civil liberties movements in India.

Indira’s rise and fall, from her early ‘socialist’ gestures to Operation Bluestar leading to her assassination illustrated the way in which the political landscape of India was changing. Violence became the order of the day. The spectacular victory of Rajiv Gandhi notwithstanding, the Congress system was falling apart. Coalition politics, the rise of regional forces, the blooming of identity markers as part of Machiavellian calculations, and the normalisation of corruption and scams—it was clear that the political realm had become increasingly separated from Gandhi’s conscience and Nehru’s vision. And now as my hair is turning grey I see yet another twist in our political history—the unholy alliance of neoliberal economics and the social conservatism of religious nationalism. Under these changed circumstances filled with violence, herd mentality and anti-intellectualism, I ask myself whether it is still possible to revisit Nehru, and learn a couple of lessons from him.

Modernity and romance with a civilisation

To begin with, I think, it is important to understand the mind of Nehru and his worldview. Yes, he was ‘modern’ in the sense that, as The Glimpses of World History would indicate, he was heavily influenced by the major transformations that post-Enlightenment Europe was passing through. The critical enquiry of science, the promise of industrial revolution, the turning point in human thinking through the discourses of Marx, Freud and Darwin, liberal philosophy, and above all, the method of Marxian historical method and socialist experimentations—Nehru embraced the spirit of modernity.

Yet, his modernity was subtle, with a deep sense of humility and wonder. This possibly led him to ‘discover’ India. In a way a careful reader of The Discovery of India would agree that it was the story of a romantic (yet critical) engagement between a modern mind and an old civilisation like ours with its many layers, and peaks and valleys. Far from debunking all civilisational values and aspirations, Nehru could retain a sense of enchantment. At Sarnath near Benaras, he could see the Buddha preaching his first sermon; he could still hear the inspiring Upanishadic prayer: “Lead me from the unreal to the real, from darkness to light, from death to immortality!” And in the Bhagavad Gita, he saw “an inner quality of earnest enquiry and search, of contemplation and action, of balance and equilibrium in spite of conflict and contradiction.” No wonder, far from erecting a wall between new age and old civilisation, Nehru had the sensibility to observe:

We can never forget the ideas that have moved our race, the dreams of the Indian people through the ages, the wisdom of the ancients, the buoyant energy and love of life and nature of our forefathers, their spirit of curiosity and mental adventure, the daring of their thought, their splendid achievements in literature, art and culture, their love of truth, beauty and freedom, the basic values they set up.

Yet, despite this romance, Nehru retained the spirit of critical enquiry. It is important to have sensitivity to the past. But we should not keep glorifying the ‘golden past’ because, as he reminded us, such a ‘foolish and dangerous pastime’ would take us nowhere because spiritual greatness could not be founded on starvation and misery. ‘India’, he asserted boldly, ‘must break with much of her past, and not allow it to dominate the present’.

One way of doing this was to popularise ‘scientific temper’—or, “the adventurous and yet critical temper of science, the search for truth and new knowledge, the refusal to accept anything without testing and trial, the capacity to change previous conclusions in the face of new evidence”—which could help us to come out of the “heavy burden of the past”. Well, with some amount of metaphysical wonder Nehru felt that there were ‘invisible’ domains that science could not explain. Yet, for him, there was no escape from science because “it is better to understand a part of truth and apply it to our lives, than to understand nothing at all.”

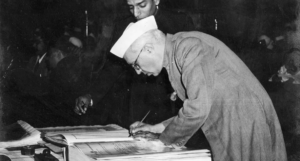

As he became the iconic prime minister of a newly independent country—traumatised by partition, characterised by unstable foundations, worried about autonomy and sovereignty in a divided world because of Cold War politics, and shocked after the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi—history posed new challenges. No wonder, Nehru’s agenda of nation-making, or ‘national philosophy’ assumed three central characteristics.

First, the state, he thought, ought to become an ethical state endowed with the responsibility of modernising a traditional country like ours with its new educators—economists, scientists, technologists, artists—promoting a ‘scientific temper’, a secular ethos with composite culture and a broadly pan-Indian national identity.

Second, with a mix of Fabian socialism and mixed economy, the state ought to play a great role in building the economic infrastructure. Big industries (or ‘temples of new India’), science labs, institutes of technology and new universities for creating a resurgent human force: rational, secular, and progressively nationalist.

Third, despite his charisma and immense popularity, and at times an uneasy relationship with the radical left as well as the extremist right, he took great care to strengthen the pillars of liberal democracy with periodic elections and a delicate balance of centripetal and centrifugal forces implicit in a country with mind-boggling diversities.

Hearing the Lost Voice

Wrote Nehru in his autobiography, “We cannot stop the river of change or cut ourselves adrift from it, and psychologically we who have eaten of the apple of Eden cannot forget that taste and go back to primitiveness.”

Nehru’s admirers are many. And at the same time, with the rise of ecological consciousness and neo-Gandhian radicalism, there is no dearth of critics. For instance, Nehru’s ‘state-centric development planning’—its centralising tendency, its reliance on techno-economist experts (symbolised by the Bhabha–Mahalanobis duo), its biases towards heavy industry—is said to have created unevenness in the country and led to the devaluation of agriculture and the rural economy, the withering away of local resources and knowledge traditions, and the widening cleavage between the educated elite and the masses.

Likewise, as ‘subaltern’ historians see the limits to ‘nationalist/bourgeois’ historiography and plead for the ‘autonomous domain of people’, we witness yet another critique. The meta narrative of Nehru is seen with suspicion, and the histories, struggles and resistances of the peasantry, the working class, Dalits and adivasis are seen as counter narratives. And again, there are political philosophers who would argue that there was a mismatch between the Nehruvian rhetoric and the actual performance. His socialism remained half-hearted; it could not really break the hold of semi-feudal landlords and the industrial capitalists; science eventually became the language of the state, and its secularism remained elitist because it could not articulate itself through the language of people’s folk religiosity.

Yet, I feel it is difficult to resist the call of Nehru. We are living at a time when mainstream politics has lost even the slightest trace of idealism; its business-like instrumental character retains no philosophic engagement, no grand dream, no romance with ideas and visions. Nehru reminded us of this lost idealism. Even in this cynical era, when I invoke Nehru’s ‘tryst with destiny’ it enchants me; it makes me feel that politics ought to be a vocation with a missionary zeal. His writings, his speeches, his grand vision: we see a source of great treasure that should not be allowed to be forgotten—especially given the mood of our times.

With neo-liberal global capitalism, we have an aspiring class that cherishes reckless consumerism and the gospel of privatisation of resources, a team of economists whose principle of ‘growth’ is devoid of social justice with the minimalist role of the government, and a brigade of hyper-masculine nationalists for whom the state is essentially a militaristic institution. Under these circumstances socialism seems to have become a bad word. Nehru was not an ideal socialist. Yet, he brought socialism in the collective conscience of the nation. And today amidst jobless growth and the increasing insecurity amongst the poor and the underprivileged, we need this spirit of socialism—an ethical state deeply engaged with collective welfare.

Finally, when the onslaught of majoritarianism or the assertion of narrow parochial identities—‘I am my religion, my caste, my race, my ethnicity’—is taking us to a dark, segmented world, Nehru’s spirited humanism or cosmopolitanism can be seen as a refreshing departure: a path leading to pluralism, the fusion of cultures and traditions and a blend of nationalism and internationalism. Amidst the noise of loud, narcissistic politics, are we ready to hear the call of this lost voice?

(Avijit Pathak is a professor at the centre for the Study of Social Systems. Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delh )