“The exceeding beauty of the earth, in her splendour of life, yields a new thought with every petal,” the nineteenth-century English nature writer Richard Jefferies wrote. “The hours when the mind is absorbed by beauty are the only hours when we really live.”

The most fertile seeds of cultural sensibility can take generations to bloom. In the twentieth century, Jefferies’s ideas became a major inspiration for Rachel Carson (May 27, 1907–April 14, 1964) — the pioneering marine biologist and writer who catalyzed the modern environmental movement and ushered in a new literary aesthetic of writing about science as something inseparable from life and inherently poetic.

Carson examined the question of beauty as a lens on comprehending the universe in a stunning speech she delivered before a summit of women journalists in 1954, later published under the title “The Real World Around Us” in Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson (public library) — the indispensable volume that gave us Carson’s prescient 1953 protest against the government’s assault on science and nature.

Carson, for whom wonderment was not only the raw material for her books but the native orientation of her mind, writes:

A large part of my life has been concerned with some of the beauties and mysteries of this earth about us, and with the even greater mysteries of the life that inhabits it. No one can dwell long among such subjects without thinking rather deep thoughts, without asking himself searching and often unanswerable questions, and without achieving a certain philosophy…. Every mystery solved brings us to the threshold of a greater one.

Nearly a century after trailblazing astronomer Maria Mitchell, in reporting on a total solar eclipse, observed that “it is always difficult to teach the man of the people that natural phenomena belong as much to him as to scientific people,” Carson writes:

The pleasures, the values of contact with the natural world, are not reserved for the scientists. They are available to anyone who will place himself under the influence of a lonely mountain top — or the sea — or the stillness of a forest; or who will stop to think about so small a thing as the mystery of a growing seed.

Unafraid of being seen as sentimental, this uncynical scientist, who eight years later would awaken the modern environmental conscience and who considered her life animated by “a preoccupation with the wonder and beauty of the earth,” adds:

I believe natural beauty has a necessary place in the spiritual development of any individual or any society. I believe that whenever we destroy beauty, or whenever we substitute something man-made and artificial for a natural feature of the earth, we have retarded some part of man’s spiritual growth.

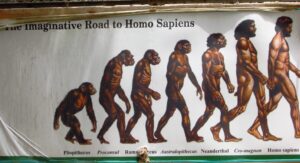

I believe this affinity of the human spirit for the earth and its beauties is deeply and logically rooted. As human beings, we are part of the whole stream of life. We have been human beings for perhaps a million years. But life itself — passes on something of itself to other life — that mysterious entity that moves and is aware of itself and its surroundings, and so is distinguished from rocks or senseless clay — [from which] life arose many hundreds of millions of years ago. Since then it has developed, struggled, adapted itself to its surroundings, evolved an infinite number of forms. But its living protoplasm is built of the same elements as air, water, and rock. To these the mysterious spark of life was added. Our origins are of the earth. And so there is in us a deeply seated response to the natural universe, which is part of our humanity.

With a cautious eye to “this destruction of beauty — this substitution of man-made ugliness — this trend toward a perilously artificial world” — cautiousness rendered tragically prescient in the retrospect of half a century of irreversible environmental destruction in the hands of merciless capitalism — Carson admonishes against the commodification of nature as a marketable resource for human use:

Beauty — and all the values that derive from beauty — are not measured and evaluated in terms of the dollar.

Looking back on the innumerable letters from readers she had received in response to her groundbreaking book The Sea Around Us — a book that crowned the New York Times bestseller list for thirty-nine weeks, made Carson the most famous nonfiction writer in America, and earned her the National Book Award — she notes that she heard from people as diverse as “hairdressers and fishermen and musicians, “classical scholars and scientists,” who all articulated a kindred sentiment:

So many of them have said, in one phrasing or another: “We have been troubled about the world, and had almost lost faith in man; it helps to think about the long history of the earth, and of how life came to be. And when we think in terms of millions of years, we are not so impatient that our own problems be solved tomorrow.”

Returning to the Jefferies lines that had so inspired her, she adds:

In contemplating “the exceeding beauty of the earth” these people have found calmness and courage. For there is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of birds; in the ebb and flow of the tides; in the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in these repeated refrains of nature — the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after winter.

Carson ends on a note of lucid hope in the face of humanity’s destructively short-sighted descent into “an artificial world of its own creation”:

For this unhappy trend there is no single remedy — no panacea. But I believe that the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.

The whole of Lost Woods is a trove of abiding wisdom from one of humanity’s most elevated and elevating minds.

(Maria Popova is a Bulgarian-born, American-based essayist, book author, poet, and writer of literary and arts commentary and cultural criticism. She is the creator of the blog, The Marginalian, that features her writing on books, the arts, philosophy, culture, and other subjects. Courtesy: The Marginalian.)