[Ninety-nine years ago today, three men walked down a road and were arrested for their temerity. Newspapers cheered on — it was day one of a “truly glorious fight” against untouchability that would shake a kingdom and captivate a nation. Where would it all end? “Bolshevism and bloodshed,” one caste Hindu was sure.

Avarnas — those without caste or ‘untouchables’ — had no right to set foot in the premises of Vaikom Mahadeva Temple or any other Brahmanical house of worship in Kerala, the country Parashurama claimed from the sea for the delight of the Brahmanas. But three men’s rebellion wasn’t about that, not officially, not just yet. It was ostensibly a campaign for the right to walk on the roads near the temple, a privilege guarded no less jealously by the orthodox establishment.

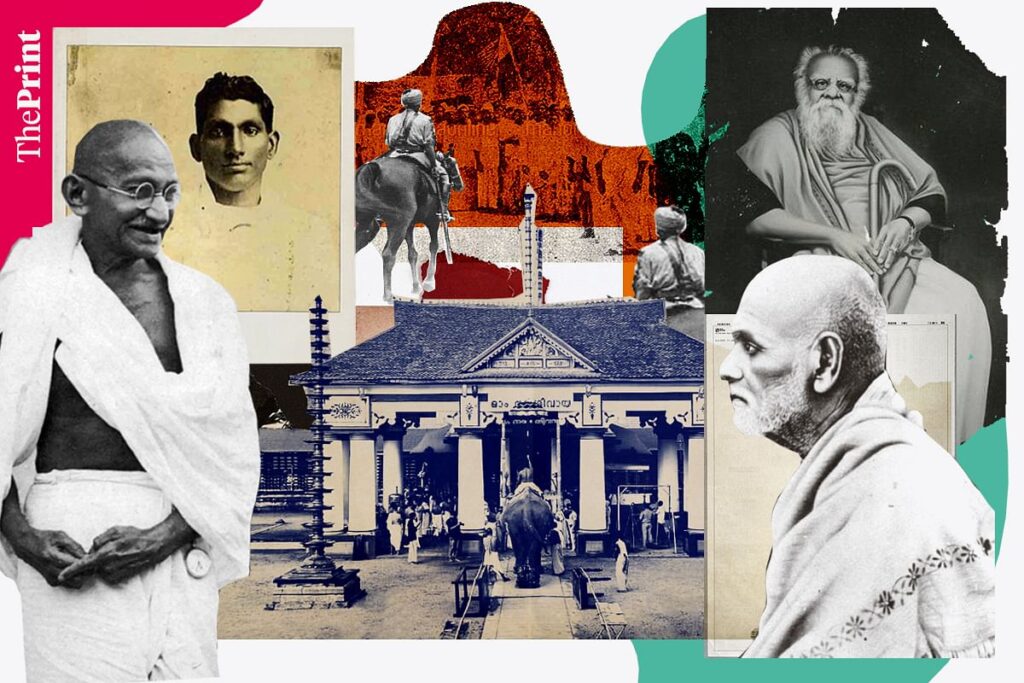

The idea for Vaikom Satyagraha was born in the ferment of an anti-caste movement that had its roots in early 19th-century Kerala and was now at its height under the guidance of spiritual leader Narayana Guru. It drew in the who’s who of social and political leaders from across the princely states of Travancore and Cochin and British Malabar as well as national figures from MK Gandhi and C Rajagopalachari to EV Ramasamy (Periyar).

Did the Vaikom Satyagraha end with a whimper? After 20 months, it won concessions so paltry they could barely be called a compromise. Great disillusionment and further struggle were its first fruits. But the movement left indelible marks on Kerala society and politics, made leaders and heroes, set a precedent for similar mass agitations, and gave hope to a dispirited Congress just three years after the Malabar rebellion was suppressed. And, 11 years after the movement ended, the Maharaja of Travancore would throw open his kingdom’s temples to the avarnas.]

Part 1: The story of how it all began

Three Men, a Great Orator, Gandhi—All That Led to the Birth of Vaikom Satyagraha 99 Years Ago

Roots of the movement

This perhaps wasn’t the first time the Shiva temple at Vaikom had become contested ground. There’s a tale you hear in Kerala, of unknown veracity, about how a large group of young men from the Ezhava caste had marched toward the temple in the early 19th century, planning to enter it. But it’s said that Velu Thampi Dalawa, the ‘prime minister’ and commander-in-chief of Travancore — later killed during a rebellion against the British — rushed to the spot with his cavalry and slaughtered them.

Anti-caste struggles picked up over the course of the 19th century, with revolts such as those led by the Ezhava warrior Arattupuzha Velayudha Panicker, who himself built temples open to avarnas. Following in his footsteps — but more famously — Narayana Guru would do the same.

On the eve of the Vaikom Satyagraha, these movements had come a long way, and it wasn’t just about religion. Jobs, literacy, a burgeoning middle class, a highly educated elite, organisation, and political representation — Ezhavas, at least, were advancing in the world.

But this was also a time of internal conflict and confusion. There were class divisions among the Ezhavas, debates over the treatment of other communities who were ‘lower’ in the hierarchy, and arguments about religion. Some wanted to stick to Hinduism, others advocated atheism or conversion. There was a sudden rebirth of Buddhism, only for it to disappear just as abruptly. Narayana Guru distanced himself from the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana (SNDP) Yogam, the organisation founded in his name, which was dominated by the Ezhava elite. The SNDP Yogam also lost a key leader with the death of the great poet Kumaran Asan in January 1924.

‘Mahavagmi’

Enter the great orator. TK Madhavan was a prime representative of the Ezhava elite, born into a paradox of privilege and oppression. Both his parents were from old, landed families in Central Travancore, his father’s, in particular, was one of the richest in the kingdom. But none of that could shield him from the realities of caste.

In a 1976 paper (Temple-Entry Movement in Travancore, 1860-1940), scholar Robin Jeffrey quotes Madhavan recollecting his school days: “My companion on my daily trip to and from the school was a Nair boy… whose poor mother was a dependent of ours. He could go straight along all the roads, whereas I, in spite of being economically better off, had to leave the road every now and then [to avoid polluting caste-Hindus]. This used to cut me to the quick.”

There’s a similar story told about Alummoottil Channar, Madhavan’s uncle or great-uncle on his father’s side, who was one of the first people in Travancore to own a car. Whenever he was about to go past a temple in this car, he would have to get out, walk through back alleyways, and get back in the car on the other side. His driver, meanwhile, could go straight past as he was an ‘upper-caste’ Nair.

The 1885-born Madhavan entered public affairs before he was 20, “organising and speaking to Ezhavas in Central Travancore, and acting as an English translator for Ezhava notables attending the representative assembly in Trivandrum,” writes Jeffrey. He became a member of this assembly, the Sree Moolam Praja Sabha, himself, standing in for his great-uncle.

Madhavan earned a reputation as a public speaker and was dubbed mahavagmi or ‘great orator’. He was also the founder-editor of the newspaper Desabhimani, not to be confused with the later Communist party paper of the same name.

Madhavan was all for staying within the Hindu fold and allying with dominant-caste Hindus to secure the rights of avarnas — not necessarily the most popular positions among the Ezhava leadership at the time. His son, Babu Vijayanath, recalls in his book Desabhimani T.K. Madhavan: Ente Achan how close Madhavan was to the pre-eminent Nair leader, Mannathu Padmanabhan.

Road to Satyagraha

According to Jeffrey, Madhavan first raised the issue of temple entry in a Desabhimani editorial in December 1917, and the matter was discussed at meetings of the SNDP Yogam and the Praja Sabha over the next three years.

He introduced resolutions calling for temple entry and for Ezhavas to be recognised as caste Hindus — and, influenced by the Non-Cooperation Movement, threatened more direct action if this didn’t happen.

Jeffrey gives an example of Madhavan taking action himself. In November 1920, he went past the restrictive notice boards on a road near the Vaikom temple and announced the following to the district magistrate: “I am an Ezhava by caste. I came to Vaikom today and went to the temple here, past the notice board posted on the road.”

The issue grew hotter over the next few years as Madhavan and his supporters organised and spoke about it in the villages of Travancore, prompting counter-demonstrations from the orthodox. Faced with stiff resistance and a conservative, elderly monarch, Madhavan knew he needed to do more.

In 1921, he met Gandhi at Tirunelveli and sought his blessings for a temple-entry agitation. Gandhi, it appears, had a mistaken impression of the Ezhavas’ condition. At first, he counselled Madhavan: “Drop temple entry now and begin with public wells. Then you may go to public schools.” But after Madhavan corrected him, he said, “You are ripe for temple entry then.” He recommended a civil disobedience campaign and said the Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee (KPCC) should take it up.

Then, in 1923, the Kakinada session of the Indian National Congress, with Madhavan in attendance, passed a resolution to set up a committee on untouchability. Next year, the KPCC, still smarting from being blamed for the Malabar rebellion, chose Nair leader K Kelappan — later known as ‘Kerala Gandhi’ — as convener of an anti-untouchability cell.

Everything was coming together for an organised agitation, the likes of which Travancore had never seen — and all roads led to Vaikom.

Part 2: On what happened during the satyagraha and its fallout

Gandhi Spoke No Sanskrit & Narayana Guru Spoke No English When They Met During Vaikom

Five stages of the campaign

On 30 March 1924, three men — an ‘upper-caste’ Nair, an Ezhava and a Dalit Pulaya — “dressed in khaddar uniforms and garlanded”, and followed by a crowd of “thousands” tried to use the roads. The three were arrested and sentenced to six months in prison when they refused to furnish bonds for good behaviour.

In a 1976 paper (Temple-Entry Movement in Travancore, 1860-1940), scholar Robin Jeffrey identifies five stages in the long campaign that followed. The initial phase saw a daily “ritual of satyagraha and arrest” that continued until 10 April, when the government decided to cease making arrests.

The next few months saw the police barricade the roads against the satyagrahis, who sat in front of the barricades, fasted and sang patriotic songs — and suffered attacks from “thugs” dispatched by caste Hindus. This was also the period when national leaders such as C. Rajagopalachari and E.V. Ramasamy (Periyar) visited and offered advice to the volunteers.

But this wasn’t the first time Periyar, who would be arrested twice during the campaign, was associated with the anti-caste movement in Kerala. Just the previous year, he’d been involved in an incident that exposed some of the ideological cleavages among the Ezhavas. At a meeting in Kottayam, Madan Mohan Malaviya — visiting Travancore on Madhavan’s invitation — had exhorted his audience to chant ‘Ramaya namah’. Led by Periyar and the atheist leader Sahodaran Ayyappan, many responded with precisely the opposite: ‘Ravanaya namah’.

Nevertheless, Periyar came together with Madhavan and other ideological rivals to play a noted role in the Vaikom Satyagraha, which entered its third stage after the death of one of its most intractable foes, Maharaja Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma, in August. His successor, Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, was a boy, and power passed into the hands of a regent: Maharani Sethu Lakshmi Bayi.

The regent immediately released the 19 satyagrahis who had been jailed in April, while the campaign continued much as before. But now, the attention was on two jathas (marches) of caste Hindus that traversed the state in support of the movement — a triumph for Madhavan’s policy of allying with the dominant castes. A resolution calling for the opening of roads around temples was also introduced in Travancore’s legislature on 25 October 1924, and was defeated by a single vote.

The fourth phase began with Gandhi’s visit to the state in March 1925. He spoke to all parties but was only able to get the police to withdraw their barricades — in exchange for the satyagrahis promising not to enter the forbidden zones.

The final stage was a period of “waning interest” that lasted until November 1925, writes Jeffrey. By this point, the government had completed alternative roads near the temple that were open to the avarnas, while a few lanes remained closed to them. The last satyagrahi was withdrawn on 23 November.

The guru, the Mahatma and the Malayali Brahmana

Does the swamiji speak English? No. Does the Mahatma speak Sanskrit? No. That’s how a well-known conversation between Gandhi and Narayana Guru began on 13 March 1925.

This interaction between the two came after a misunderstanding over the possibility of violence in the campaign the previous year. In June 1924, an Ezhava journalist reported an informal conversation with the guru, in which the latter had purportedly said, “the volunteers standing outside the barricades in heavy rains will serve no useful purpose…They should scale over the barricades and not only walk along the prohibited roads but enter all temples…It should be made practically impossible for anyone to practise untouchability.” Gandhians were alarmed, and the guru wrote to Gandhi to say that there had been misreporting and misunderstanding.

When the two met in March 1925, it was at Narayana Guru’s Sivagiri ashram, wrote Kottukoyikkal Velayudhan in Sreenarayanaguru Jeevithacharithram. Gandhi spoke in English, the guru in Sanskrit, and N. Kumaran translated. A few of their exchanges follow:

Gandhi: Some say that a non-violent satyagraha will be useless and violence is needed to secure rights. What is the swami’s opinion?

Guru: I don’t think violence is good.

Gandhi: Do the Hindu dharmashastras prescribe violence?

Guru: It can be seen in the puranas that it’s necessary for kings and others, and they have used it. It may not be right for ordinary people.

Gandhi: Some are of the opinion that religious conversion is needed and that’s the true path to freedom. Would the swamiji agree?

Guru: It can be seen that people who’ve converted are gaining freedoms. When people see that, they can’t be blamed for saying religious conversion is good.

Gandhi: Does the swamiji think Hinduism is enough for the soul to attain moksha?

Guru: Other religions also have a path to moksha, don’t they?

The conversation continued in that vein. The references to conversion may be seen in the context of the situation in Travancore, where conversion to other religions such as Christianity removed the disabilities of untouchability, at least officially; an avarna who had become Christian could do much that was forbidden to his Hindu counterpart.

A few days before, at Vaikom, Gandhi had had another conversation the history books have recorded, with a Namboothiri Brahmana of the Indanthuruthi mana — the custodians of the Mahadeva temple. He was accompanied by others including Rajagopalachari, Mahadev Desai and the Nair leader Mannathu Padmanabhan.

When Gandhi questioned restrictions on avarnas using public roads, the Namboothiri replied that it was the fruit of their karma, and cited the long-held rights of the Brahmanas. He then asked Gandhi why he thought the avarnas were oppressed. When Gandhi made a comparison to Jallianwala Bagh, the Namboothiri asked if he were calling Shankaracharya a ‘Dyer’ — in Kerala, many of the laws regarding caste were codified in the mediaeval Shankarasmriti, a book traditionally attributed to Shankaracharya (believed to have been a Kerala Brahmana himself), although the consensus now is that it’s a much later work.

The argument went nowhere, with the Namboothiri resorting to silence when Gandhi tried to press him. It revealed just how inflexible orthodox attitudes continued to be, and that the anti-caste movement still had a long and difficult road ahead.

Aftermath

The tangible gains of the movement had been few, and it ended with a compromise after the government constructed a few new roads that avarnas could use without “polluting” the temple. A few lanes and of course, the temple itself, remained barred to them. More satyagrahas on the Vaikom model followed in the next few years, but bore little fruit; the avarnas seemed no closer to temple entry.

However, the Vaikom Satyagraha set in motion many forces that would go on to transform the politics of Travancore and the entire region of Kerala. Its leaders attained immense stature — Madhavan became a towering figure among his contemporaries and continued to be an indefatigable organiser, while others such as K. Kelappan and K.P. Kesava Menon — the president of the Kerala Pradesh Congress Committee and editor of Mathrubhumi — could mobilise their accrued prestige to revitalise the Congress in the wake of the Malabar Rebellion.

The eventual Temple Entry Proclamation of 1936 was the result of complex politics and the government led by the diwan, Sir C.P. Ramaswami Iyer, being alert to the dangers staring it in the face. Militant rhetoric was gaining popularity among disgruntled Ezhavas, while the community was also drifting closer to Christians and Muslims; in 1933, the representatives of 12 Christian, Muslim and Ezhava organisations formed the Joint Political Congress to boycott that year’s election and demand greater representation in the legislature and in government service. And above all, there was the looming threat of mass conversion, especially to Christianity, which haunted a government that desperately wanted to preserve Travancore’s ‘Hindu’ identity, Jeffrey wrote.

The rest of Kerala would take longer to follow suit, with avarnas only being granted entry to all temples after more satyagrahas and even after Independence.

As for T.K. Madhavan, an injury suffered during a later agitation — when he was following Narayana Guru’s directions to push forward forcefully if physically stopped — would continue to haunt him for the rest of his foreshortened life. His final illness struck him in 1930 when he was resting in the shade of almond trees at his home.

As his friend and occasional rival, the poet Kumaran Asan, once wrote, ‘Kaalam kuranja dinamenkilum arthadeergham’. The days were short, but they were long with meaning.

(Courtesy: The Print.)