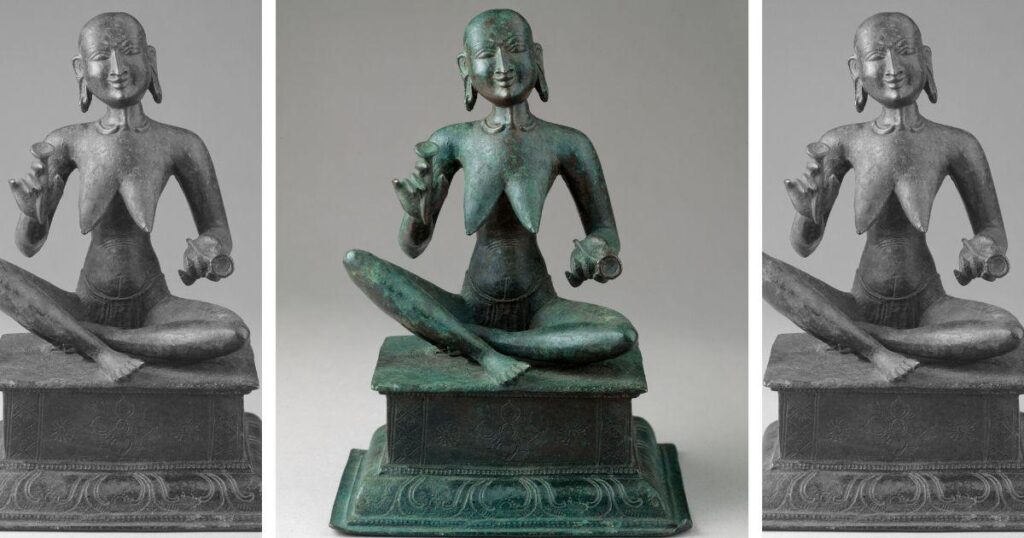

There is an apocryphal, though riveting tale of Karaikal Ammaiyar, a 6th century poet-mystic of modern-day Tamil Nadu. Abandoned by her husband who viewed her as a goddess after witnessing her miracles, she found herself harassed by a society that found it unpalatable for a married woman to live alone. Legend has it that this is what led Karaikkal Ammaiyar to seek divine intervention to do away with her conventional beauty and break free from the shackles of social conformity.

In a striking verse, Karaikkal Ammaiyar writes a self-portrait of sorts:

A female ghoul, with shriveled breasts, bulging veins

hollow eyes, white teeth, a bloated belly,

Red hair, fangs …

Ammaiyar is one of the 63 Nayanmar mystics from Tamil Nadu who celebrate the divine as Shiva. Karaikal Ammaiyar was one of three Nayanmar women mystics – the other two being Isaignaniyar and Mangayarkarasi. Along with the Alwars, devotees of Vishnu, the Nayanmars are considered amongst the earliest proponents of Bhakti, a movement that spanned from the 6th century all the way to the 18th century.

The Bhakti movement arose from a desire to have a direct relationship with god while rejecting the rules and rituals imposed by society. Mystics of the movement composed poems and hymns that described their feelings towards the divine. The poems were often of devotion and were stated in personal terms. The mystics themselves came from regions across India – Kashmir to Kerala – and varied backgrounds, from marginalised to the privileged and cobblers to kings.

But among Bhakti mystics, women are a minority. A few, including Akka Mahadevi, Andal and Meera, are well known outside their regions unlike Karaikkal Ammaiyar, Soyarabai, Lal Ded and Bahinabai whose lives and work offer sobering lessons about the inequality and discrimination that continue.

Avagha rang ek zaala

Rangi rangalá shri ranga

Naahi bhedhache te kama

Paloni gele krodha kama

“Avagha rang ek zaala” is how 14th century Bhakti saint Soyarabai refers to all colours (people) being the same in her abhang – a devotional poem in Marathi. Soyarabai’s struggles began at birth when she was born into the oppressed Mahar caste in present-day Maharashtra. Hailing from a caste of “untouchables”, she was not allowed to enter the Vithoba temple in Pandharpur. Her husband, Chokhamela was also refused entry into the temple.

While the abhangs of Soyarabai heard today are revered as devotional verses, her social message and lived experience of caste and gender discrimination is largely unacknowledged and glossed over.

Women mystics born into privileged castes faced gender discrimination. Lal Ded, who is believed to have been born in a Kashmiri Pandit family in the 14th century, was married at a young age. After facing years of abuse at the hands of her mother-in-law and husband, she walked out of her marital home to pursue her devotional path of Shaivism.

Her vakhs, or poetic verses, one of the earliest known works in Kashmiri, are written in the first person and are a continual search for answers. A woman who had no fear or desire for approval from others, Lal Ded says in one of her vakhs, “tavay mey hyotum nangay natsun”, indicating someone who wanted to dance naked in her spiritual journey.

Like Lal Ded, Bahinabai, the 17th century mystic from Maharashtra, was born into a Brahmin family. However she chose to fight her battles within the confines of her marriage. Bahinabai’s story is one of angst and acceptance.

“A woman’s body is a body controlled by somebody else. Therefore, the path of renunciation is not open to her,” she says. Bahinabai was a child bride married to a man nearly three decades older. Her abhangs speak of her struggles being married to a cruel man and how she internalised the oppression she faced on a daily basis.

Bahinabai’s poetry and folklore reveal her prolonged efforts and the divine intervention that lead to her husband’s eventual transformation. Caught between duty and devotion Bahinabai’s story is one of how patriarchy trumps all else. A concept all too familiar to women everywhere even today.

In recognising some or all of these mystics, regional, religious or other parochial pressures lead to hagiographies and myth-building around them. Celebrating these women as Bhakti saints and an inspiration, while not acknowledging their oppression and lived experiences is an act of creating, what Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls, “a single story”.

As Adichie says, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they aren’t true, but they are incomplete.” Instead of seeing these Bhakti women poets as uni-dimensional and narrating a single story of their devotion, their struggles need to be acknowledged, and that such issues continue in society today. While celebrating their abhangs and vakhs, it is important to address these inequities with the same fervour.

(Chitra Srikrishna is a carnatic vocalist and adjunct professor of music at Ahmedabad University. Courtesy: Scroll.in.)