The Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG), founded in 1947, belonged to a moment of transition and optimism. Last year, it celebrated its 75th anniversary along with the country. So, this is a good time to look back at the PAG’s claims and achievements.

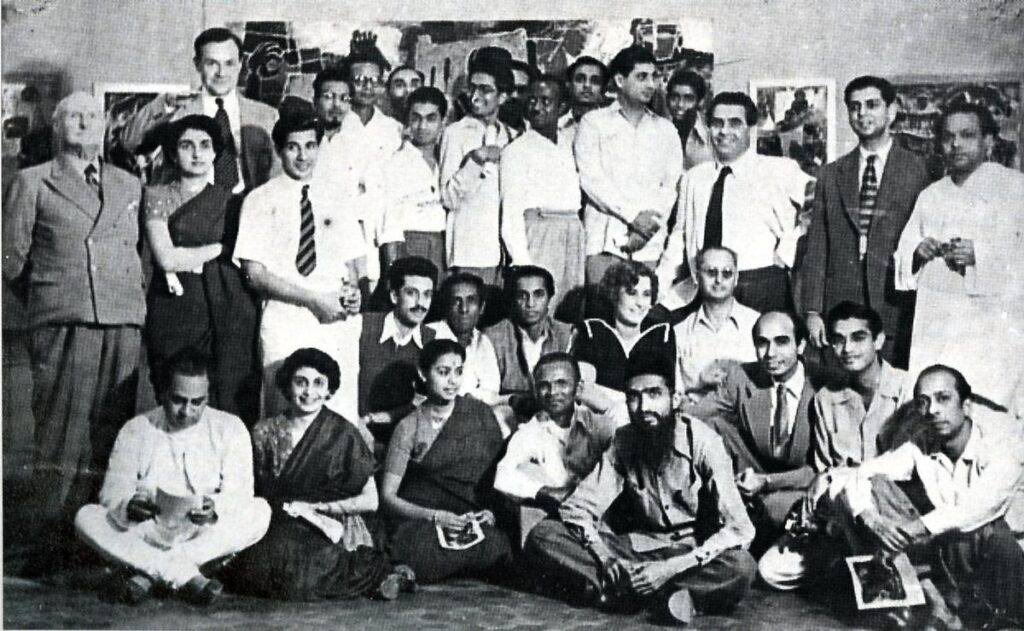

The PAG’s founding members were F.N. Souza (1924-2002), M.F. Husain (1915-2011), K.H. Ara (1914-1985), S.H. Raza (1922-2016), H.A. Gade (1917-2001), and S.K. Bakre (1920-2007). The group was led by Souza, who was its ideologue, spokesperson, and in later years, its lone stormtrooper.

However, when Souza, Raza, and Bakre left for Europe after the group’s first exhibition in Bombay in 1948, several new members were added, including A.A. Raiba, N.P. Chapgar, Krishen Khanna, V.S. Gaitonde, Akbar Padamsee, and Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, its only female member. Subsequently, Mohan Samant, Ram Kumar, and Tyeb Mehta also came to be associated with the group.

From being an exclusive club of six, with these inclusions, the PAG came to stand for a phase of post-Independence Indian modernism: its founders and supporters saw it as the fountainhead of true modernism in Indian art. According to Souza, the group was conceived as a protest against the J.J. School of Art, which perpetuated academic realism, and from which he was expelled; and the revivalists of Indian art, whom he considered chauvinistic and stuck in time. The immediate provocation, however, was the rejection of his submission by the Bombay Art Society. It occurred to him that it would be easier to take on “the kind of art inculcated by the J.J. School of Art and exhibited in the Bombay Art Society” by ganging up. He believed that its members were “the best and the most vital among us”: that its formation “coincided with the Independence of India was symbolic, but coincidental”. In his view, the group’s work was self-generative, owing nothing to what came before. As Souza wrote in the group’s catalogue of 1949: “[O]ur art has evolved over the years of its volition. Out of our own balls and brains.”

Though brilliantly polemical, Souza was given to bragging and simplifying facts. There was more context and history to the group’s emergence than he cared to admit. The emergence of Bombay as a centre of the cotton trade at the turn of the century meant that it attracted a large number of people from different regions, religions, and castes. Its subsequent development into a cosmopolitan port city and India’s commercial capital, and India choosing to be a secular modern nation post-1947 all helped the Progressives develop in the way they did.

‘Almost anarchic’

While Ara was a Dalit who worked as a car-washer, Souza, Husain, and Raza were members of underprivileged marginalised communities. Souza and Raza nurtured leftist sympathies and, taking a cue from the Progressive Writers’ Association, called themselves the Progressive Artists’ Group. In the beginning, they painted landscapes or pictures of local life with beggars, farmers, potters, or street vendors in a loose realist manner with modernist overtones. The focus shifted quickly from subaltern subjects to self-expression and to formalist issues after they came into contact with three Jewish immigrants from fascist Europe —Rudolf von Leyden, Walter Langhammer, and Emmanuel Schlesinger—who introduced them to Western modern art, especially German expressionism. As art critics, artists, and entrepreneurs, the trio also became mentors and patrons to the Progressives.

Reflecting on these shifts, Souza wrote in the catalogue of his second solo exhibition: “My last exhibition was damned as communist propaganda by retrogressives. This one is going to be damned as sexual exhibitionism by moralists.” A year later, in the catalogue of the PAG’s first exhibition in Bombay, he wrote: “I do not quite understand now, why we still call our group ‘Progressive’. We have changed all the chauvinist ideas and the Leftist fanaticism which we had incorporated in our manifesto at the inception of the Group…. Today we paint with absolute freedom for contents and techniques, almost anarchic; save that we are governed by one or two sound elemental and eternal laws, of aesthetic order, plastic coordination and colour composition.”

Independence opened up new and far-reaching possibilities: while it brought with it the need for nation-building, it also lifted the moral compulsion to take an anti-colonial nationalist stance. As citizens of independent India, artists were free to respond to social and political experiences as individuals, to critique the state and society, and to give precedence to one’s subjectivity, as Souza did. With India opting to be a modern secular nation with aspirations to become a world player, cultivating international ambitions became a desirable choice for individual artists. Especially as Western modernism was touted as a universal phenomenon rather than a regional cultural development. So, beginning with Souza in 1949, several PAG members and their associates, including Raza, Bakre, Padamsee, Ram Kumar, Mohan Samant, and Mehta left for London or Paris to become a part of international modernism and, perhaps, to represent India in the international cultural arena.

With this exodus, only Ara, Gade, and Husain were left in India. Of them, Ara continued to plough his lonely furrow without any change in content or style; Gade returned to academics and gradually faded into oblivion. The group became inactive and was finally disbanded in 1956. Husain alone remained committed and chose to align with the Nehruvian project of transforming India into a modern secular nation through industrialisation, cultivation of science, adoption of modern technology, and urbanisation, without abandoning its old cultural expressions or forgetting its villages, which were the fulcrum of the nationalist movement.

The planning and building of Chandigarh, in which Jawaharlal Nehru was personally invested, exemplify what this meant in cultural terms. Nehru wanted it to be a planned modern city, a symbol of independent India’s identity, as opposed to Lutyens’ Delhi, a symbol of British imperial power. But he did not shy away from seeking the collaboration of American and European architects to achieve this. Initially designed by Albert Mayer and Matthew Nowicki, it was finally built by Le Corbusier, combining modern city planning, modern materials and technology with Corbusier’s mid-century modernist style and a veneer of vernacular elements like concrete jalis and rough-textured walls recalling the mud walls of Indian village homes.

Husain’s art

Husain adopted a similar stance, combining modernist art language with formal elements and bright flat colouring drawn from Indian art. The ground for such an eclectic visual language was laid by his visit to the large exhibition of Indian art in New Delhi in 1948. Souza accompanied him.

In a 1992 interview with Yashodhara Dalmia, Husain said, recollecting his visit: “I came out with a set of five paintings in 1948 after visiting Delhi with Souza…. Till then I was influenced by the Expressionists. After visiting the exhibition, I combined three periods, the form of the Gupta period, the strong colours of the Basohli period, and the innocence of folk art and worked on it and then came out with five paintings which were shown at the Bombay Art Society in 1949.”

Initially, the impact of this eclectic mix was powerful and effective, but it lasted only for a short while, culminating in the 1951 painting “Man”, an authentic image of life in an urban slum, and perhaps the last sympathetic representation of the urban poor in Husain’s work. After this, his representations of life and landscape became more panoramic and evocative (“Zameen”, 1956), and emblematic and ambivalent (“Between the Spider and the Lamp”, 1958) while retaining their expressive power.

Husain’s work became what he called “a celebration of India”, widely appealing but largely vacuous. Husain recognised this, and in a 2005 interview with Soma Choudhury, he confessed: “I reached my peak as an artist in the late 1950s. All my other work is a manifestation of that.” The 1968 Ramayana paintings, his first step towards the popularisation of his work, were done following the socialist leader Ram Manohar Lohia’s suggestion to do something that would appeal to Indian villagers. The subsequent series based on the Mahabharata and his take on various historical figures and events effectively turned modern art into contemporary popular art. They helped Husain become India’s official modern artist and a household name. But, despite his sporadic avant-gardist gestures, such efforts eroded his standing as an artist.

And finally, as India’s collective commitment to secularism and an inclusive modern society began to be challenged by the political Right, these very efforts at forging a secular collective identity and a sense of national belonging, cutting across religions, brought him trouble and forced him into self-exile. The subsequent fall of Nehru from grace showed that Husain’s experience was not a singular event but a sign of changing political power structures, and social and cultural perspectives.

Raiding ancient art to develop one’s visual language or one’s thematic repertoire is common among modern artists. Souza, who was with Husain on his 1948 trip to Delhi, was captivated by the sensuality of the yakshis and mithunas, or as he put it, “girls wearing nothing but smiles”.

Their traces can be easily noticed in his works shown in the PAG’s 1949 exhibition. But in his later works, they are wrenched out of their cultural context and transformed, using an expressionist idiom, into manifestations of his libido, just as he transformed Christian iconography into expressions of social anger and personal angst. While Husain played down the sensuality of Indian sculpture, Souza heightened it. But displaced and transformed and placed squarely within the Western modernist tradition, where the use and distortion of religious iconography for personal expression or social commentary were normal, they did not attract the kind of hostility Husain drew. However, like Husain, Souza also did not achieve the success he hoped to achieve.

Souza’s achievement

Souza’s work fell well within the kind of work British artists like Graham Sutherland and Francis Bacon were doing at that time, and his oeuvre stood well against theirs. By 1957, important critics like David Sylvester and John Berger and writers like Stephen Spender recognised the energy and power in his paintings and writings, but they remained somewhat baffled, not knowing where to place him. Berger wrote: “I find it quite impossible to assess his work comparatively. Because he straddles several traditions but serves none.” As for Husain, by the early 1960s his best work was behind him.

The experience of other Indian artists who went to Europe was similar. They realised that despite the role of non-Western arts in developing modern Western art, which was presented as a universal model, European art establishments were not ready to see contemporary artists from non-Western countries as equals. Bakre, for instance, had some success as a designer but not as a sculptor. Even when they received sympathetic attention from French poets of the Left like Jacques Dubois, Surrealists like Louis Aragon and Paul Éluard, and artists like Alberto Giacometti, they were seen as derivative late-comers by museum directors and critics. Raza alone had a modicum of critical success in Europe in the late 1950s after he shifted to an abstract expressionist idiom.

By the early 1960s, they were convinced that they carried more Indian cultural baggage than they had believed and that Europe was not the place for them. Gradually, all except Souza returned to India, where they continued to be seen as the masters of post-1947 modern art even while living abroad.

Looking back at the PAG from our vantage point, it is easy to see that they were not the sole nor the first Indian artists to have drawn lessons from modern Western art. Gaganendranath and Rabindranath Tagore, Amrita Sher-Gil, and Ramkinkar Baij had already done so with considerable success before them without joining the internationalist bandwagon. Souza and Husain consolidated the achievements of their predecessors and turned it into a shared project for Indian artists of their generation rather than beginning afresh.

Similarly, the PAG members were on different pages stylistically and in their achievements. Raza, Gaitonde, Ram Kumar, and Gade quickly moved away from figurative expressionism to nature-based abstraction. They also peaked as artists at different points in time. While Souza, Husain, and Padamsee peaked around 1960, others like Raza and Mehta came into their own much later. Ram Kumar, Padamsee, and Mehta added an existential streak to the group’s expressionist aesthetics, but Mehta alone continued to develop the original impulse and progress continuously.

Expressionism and the School of Paris, which Souza identified as the group’s collective aesthetics, had already passed its heyday by 1947, and America had displaced Paris as the centre of avant-garde modernism. PAG members connected with American art only in the 1960s through visits facilitated by the Ford Foundation (Krishen Khanna, Mehta and Gaitonde) or academic appointments (Padamsee and Raza). Raza and Mehta were again the only two who clearly benefited from it.

By the early 1960s, Indian artists, partly disenchanted by the experience of the Progressives, ceased to be enamoured of internationalism and began to fix their gaze on things closer home. The older debates around indigenism and modernism were revived.

Art critic Geeta Kapur noted, “concepts of progress, internationalism and the avant-garde, all of which together constitute the substance of modernism, came to be re-evaluated”. This gave rise to multiple positions. While some veered towards styles identifiable as Indian, others tried to rethink modernism and look at the social and the political through the lens of the regional, the local, and the experiential. And that reduced the PAG adventure from being the source of modernism in India into a historical moment in time.

However, these changes did not affect the members of PAG, as Raza’s 1985 letter to the critic S.I. Clark mourning Ara’s death makes clear. He wrote: “Your letter gives me the sad news of Ara’s death. Something precious deep within me ceases to beat. And then, echoes and memories emerge in an endless chain: our association, youthful dreams, our collective action and our own individual work, in Bombay, during the years, 1943-50. I think I have shared with Ara, the richness of feeling in the kingdom of the heart, a certain emotional approach to life, where only the authenticity of the MAN really mattered. There was no barrier of caste or creed or nationality. These petty prejudices which existed then in abundance and exist even now all around us. Our reactions were spontaneous, almost raw, dictated by animal-like perceptions and we painted and painted endlessly. It did not matter if we were right or wrong, we did make mistakes. But we lived and acted, responding to a mysterious life-force and the logic seems to hold good even today.”

Raza sums up the strengths and weaknesses of the PAG, including the fact that its members continued to stick to the values of their youth long after Indian art and their own practice had changed.

(R. Siva Kumar is an art historian and curator based in Santiniketan. Courtesy: Frontline magazine.)