Budget 2023 Has Chilling Implications for India’s People

Jayati Ghosh

The annual budget is generally supposed to be a statement of not only the Union government’s actual and proposed revenue raising and spending plans, but also of its general economic policy intent. If so, the indications this year are chilling.

It seems that the Narendra Modi government has decided, in an election year, that general elections can be fought and won without efforts to improve the material conditions of the bulk of the people, and even simply ignoring their suffering. (Presumably other strategies are to be used for the coming elections.) Instead, the focus of the government will be on infrastructure investment, which may have some positive fallout over the longer term, but in the short run will only generate profits (and kickbacks) for a very select few.

The Economic Survey already suggested that the government is innocent of – or in denial about – the material conditions of the vast bulk of the Indian population. Remember that aggregate employment rates are at historically low levels; formal employment is coming down and job losses are hitting even the most “dynamic” sectors like IT; median money wages are lower than they were two years ago; official surveys are finding horrifying nutrition indicators and micro surveys reveal evidence of growing incidence of absolute hunger. But for the finance ministry, there is hardly any mention of any of this, as cherry-picked data are produced to suggest that the period since 2014 (and before that, the term of the A.B. Vajpayee government of 1999–2004) have been golden periods for the Indian economy despite all the challenges. In other words, “sab changa si”, and our only concern is how to insulate ourselves from global economic problems, since we apparently have none of our own.

One important caveat: we need to remember that most of the numbers for the Union Budget 2023-24 – both the declared intentions for the coming year and the so-called “Revised Estimates” for the current financial year 2022-23 – are dubious. The current fiscal year’s numbers are based on the available (and still preliminary) data for April to December 2022, since numbers for January 2023 are not yet available even to the finance ministry, and February and March have yet to occur. Since the numbers for the last quarter of the year are as yet unknown, the finance ministry is free to fill in whatever it likes as the total for the entire year, and thereby claim whatever to meet whatever revenue, expenditure and fiscal deficit targets it chooses. And it can also declare whatever numbers it chooses in the coming year without informed scrutiny about the underlying assumptions.

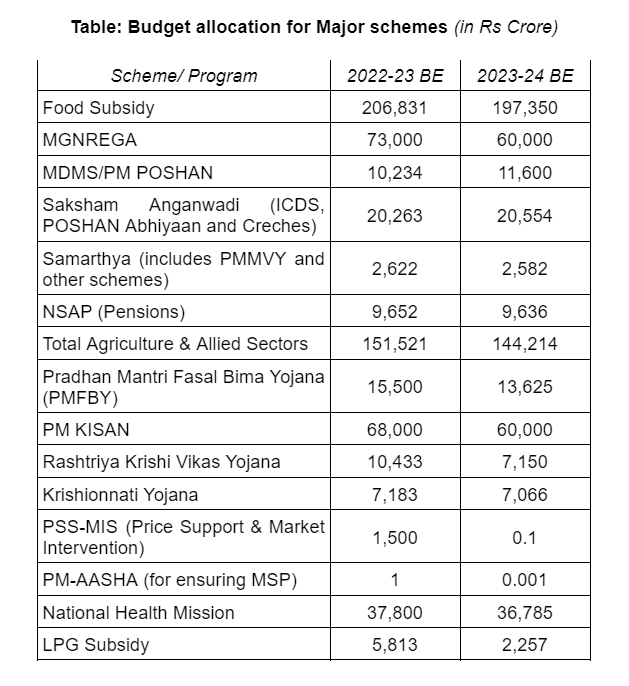

Given this, the numbers provided in Budget 2023-24 are startling to say the least. It is safe to say that we have not experienced such a savage cutback of essential social spending in a very long time, and certainly not in the last two decades. In a period of falling employment and lower real wages especially for the rural poor, the allocation for the MNREGA has been cut by around one-third from the likely spending in the current year, to only Rs 60,000 crore. The group People’s Action for Employment Guarantee has estimated that the allocation for the coming year should be at least Rs 2,72,000 crore if the promise of 100 days’ work is to be met even for those who worked on the programme in the current year – this would be only around one-fifth of that.

The massive cut in the allocation for the food subsidy by nearly one-third is similarly striking given all the evidence on undernutrition and absolute hunger. The increase in allocation for the National Health Mission will not keep pace with inflation, implying a cut in real terms and an even bigger cut in terms of per capita spending. The much-celebrated public health insurance scheme PM Swasthya Suraksha Yojana was allocated Rs 10,000 crore in the current year but will apparently manage to spend only Rs 8,270 crore. For the coming year, the allocation is only Rs 3,365 crore! So what will happen to all the unfortunates who are currently covered under this scheme – will their “insurance” simply lapse?

Unlike most countries in the world that significantly increased public spending on schooling to allow for students to deal with learning losses during the pandemic, the Indian government did not do so. Instead, even the budget estimate of Rs 63,449 crore for 2022-23 is not expected to be met, with a shortfall of Rs 4,396 crore. And the budget outlay for the coming year is only Rs 5,356 crore more, once again just about keeping pace with expected inflation. The higher education outlay is slated to increase by a pathetic Rs 3,267 crore, suggesting no real expansion.

The finance minister spent what seemed like an aeon talking about agriculture – but the total budgetary outlay for agriculture is down, as is that for rural development. Some of the reductions are striking: the Market Intervention Scheme that is supposed to provide price support for farmers when market prices fall below a certain minimum level was announced with much fanfare a few years ago. But the allocation for that scheme has fallen from Rs 1,500 crore to only Rs 1 lakh! (You read that right – it’s not a typo.) The finance minister announced that the PM-KISAN payments would increase from Rs 6,000 per farmer to Rs 8,000 per farmer in what is clearly one of the few pre-election sops – but that is not reflected in the expenditure budget, where the amount allocated is the same as the previous year, Rs 60,000 crore.

Even the much-hyped capital expenditure numbers are also padded up in ways that should now be familiar over the tenure of this finance minister. For example, support to oil companies is included under “capital expenditure to fund the green transition”!

One of the biggest cons is in the declaration that state governments are being provided hugely increased funds to finance their capital expenditure. In reality, the total transfers to the states are projected to come down. In 2021-22, such transfers amounted to Rs 4,60,575 crore, but they were reduced to Rs 3,67,204 crore in Budget 2022-23, and the Revised Estimates suggest only Rs 3,07,204 crore will be transferred in the current fiscal year. The Budget 2023-24 provision is for Rs 3,59,470 crore. Meanwhile the states’ share of tax revenues has come down to only 30.4% in the upcoming Budget, down from 33.2% in 2021-22, and a very far cry from the 42% share promised by the 14th Finance Commission.

All this is very bad news for ordinary people, and also for domestic demand, since this will impact directly on mass consumer demand. This has already affected industrial production: consumer durable production in 2021-22 was 13% lower than in 2018-19, while non-durable consumer goods production increased by less than 1% over the same period. In the circumstances, it is hardly surprising that private investment as a share of GDP fell from 23.1% to 19.6% over those years.

Clearly, this government is either not interested in genuine macroeconomic revival or persists in the foolish belief that just announcing big capital spending plans can cause people to overlook the actual realities. It is evident that stock markets – after the initial knee-jerk euphoria – were not fooled by this; and it is increasingly evident that international investors are not going to be fooled either, especially as the Adani unravelling continues. It remains to be seen whether the electorate will once again persist in being fooled.

(Jayati Ghosh is a development economist and a professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Courtesy: The author’s blog at networkideas.org.)

❈ ❈ ❈

A press statement by Right To Food Campaign, “Union Budget 2023-24: Betrayal to the People of India”, adds:

India is facing serious inequality where only 5 percent of Indians own more than 60 percent of the country’s wealth while 50 percent of India’s population possesses only three percent of the wealth according to Oxfam India’s report. In this context, spending on social protection schemes such as the PDS, anganwadis, pensions and MGNREGA became especially important. But the Government of India has betrayed the hardworking people of this country by showing no sense of accountability in this year’s Union Budget.

- The Right to Food Campaign condemns the sheer insensitivity of the Central Government’s policy decision which will result in reducing the ration entitlement of 81 crore people by 50%. Till December 2022, the ration cardholders were entitled to a 10 kg ration per person since April 2020 (5 kg under NFSA at a subsidized price and 5 kg free under PMGKAY) but with the discontinuation of the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) from January 1, 2023, the ration entitlement of people is halved- and they will be entitled to only 5 kgs ration per person (normal NFSA entitlement) instead of the current 10 kgs ration per person (NFSA+PMGKAY).

- The requirement, therefore, was to continue the additional foodgrains under PMGKAY and expand the PDS to include non-ration card holders and distribute pulses and oils. However, the budget has reduced the food subsidy allocation by over ₹89,000 crores. The ₹1.97 lakh crore that has been allocated is barely enough to meet the requirements of the regular entitlements under the National Food Security Act.

- Women and children of the country have once again been ignored even when they have been most affected by the pandemic and the continued economic severity. The allocations for samarthya (including maternity entitlements), and PM POSHAN (mid-day meals) have reduced considerably this year as well (see table 1). In the Saksham Anganwadi which includes Anganwadi services, a scheme for adolescent girls and Poshan Abhiyan remains almost the same as compared to the previous year. The Government of India’s fight against malnutrition and the efforts to ensure nutritional security looks like a far dream through the poor budgetary allocation in these crucial departments.

- Social security pensions for the aged, single women, and disabled under the National Social Assitance Programme (NSAP) have been reduced significantly creating a major impact on the lives of the most marginalised section of society. Similarly, maternity entitlements that come under Samarthya (including PMMVY and other schemes) saw a decline in this year’s budget allocation. Recently, in an RTI reply, the government has responded that the number of women who are receiving maternity benefits is going down. A letter by a group of over 50 economists was sent to the finance minister in December 2022 with the demand to increase allocations for social security pensions and maternity entitlements. The letter stressed the allocation of at least Rs. 8,000 crores for full-fledged implementation of maternity entitlements as per NFSA norms and an additional Rs. 7,560 crores for old age and widow pension is required with an immediate increase to at least Rs.500 per month from the stagnant amount of Rs. 200 since 2006. This year’s Budget has once again failed to meet this crucial requirement.

As regards the much touted increase in capital expenditure in the budget, Prabhat Patnaik in an article “Budget 2023-24 Fails to Spur Flagging Consumption Spending” writes (extract):

The most outstanding feature of the Indian economy today is the sluggish increase in real consumption expenditure. Between 2019-20 and 2022-23, for instance, the per capita real consumption expenditure has grown by less than 5%, which is less than the rate of growth of the gross domestic product (GDP).

Even the meagre recovery from the depths of the pandemic, in short, has been investment-led rather than consumption-led. This has two obvious problems: first, such a recovery is patently unsustainable. It would simply lead to a pile-up of unutilised production capacity, of unused infrastructure, and hence of unrecoverable loans by banks that would inevitably choke off the recovery, apart from threatening the stability of the financial system itself.

Second, the basic rationale of growth is to improve the living conditions of the masses; and if the level of consumption of the masses remains stagnant, then there is little point to this growth.

The primary task before the 2023-24 budget, therefore, was to stimulate consumption in the economy, for which there had to be, above all, an increase in social sector expenditure. But this is precisely what the budget has not done.

On the contrary, what the budget has done is to squeeze government expenditure on the social sectors in order to make resources available for increasing capital expenditure even further.

Likewise, on rural development there is a reduction even in the nominal outlay. On education and health, there are small increases in outlay in nominal terms, but when inflation is taken into account these sectors would witness a decline in real terms.

All this is not surprising given the anti-consumption and hence anti-poor stance of the government. The striking feature of the 2023-24 budget is that government expenditure, including transfers to states, is expected to increase at a rate lower than the GDP; its share is supposed to fall from 15.3% in 2022-23 (revised) to 14.9%, a fall almost matching the fall in the ratio of the fiscal deficit from 6.4% to 5.9%.

The parsimony in stimulating consumption is reflected also in the decline in transfers to state governments. Transfers to the states in 2021-22 amounted to Rs 4,60,575 crore, which came down to Rs 3,67, 204 crore in 2022-23; this was further cut to Rs 3,07,204 crore, according to the revised estimates. The current budget provides only Rs 3,59, 470 crore, which, far from making up for the shortfall in 2022-23, is even lower than the budget estimates for the last year.

Since state governments are substantially responsible for expenditure on social welfare, the Centre, itself niggardly in this respect, has imposed niggardliness on the state governments as well, through its deliberate centralisation of resources that palpably undermines the federal structure.

Within the reduced central expenditure relative to GDP, there has been a sharp increase in capital expenditure. The finance minister made much in her speech of this increase in capital expenditure from Rs 7.5 lakh crore to Rs 10 lakh crore, citing this as the panacea for the scourge of unemployment that currently afflicts India.

What the finance minister glossed over, however, were four basic points: first, exactly the same amount of money, if spent on the social sector, would have at least the same employment effect. Second, this sum, if spent on the social sector, would have been directly beneficial for the working people, in whose case, as the Economic Survey presented to Parliament the previous day has admitted, there has been an absolute decline in real wages.

Third, the multiplier effects of expenditure that (via larger social sector spending) directly or indirectly, augments purchasing power in the hands of the working people, are much greater than the effects of public capital expenditure, so that the impact on unemployment, of an identical amount spent on the social sector would have been far greater than when it is spent as capital expenditure.

And fourth, much of capital expenditure “leaks” out abroad in the form of imports of capital goods, unlike in the case of a boost to the consumption of the working people, which further strengthens the point about the asymmetric employment effects of the two modes of spending.

The import dependence of capital expenditure has increased in recent years under the neoliberal dispensation, which is a major reason for the stagnation in the country’s own capital goods sector despite the investment-led recovery that we have been witnessing of late. In the absence of greater protection of the domestic capital goods sector, expecting larger capital expenditure to generate any noticeable larger domestic employment is just a pipe-dream.

The budget, instead of providing greater protection from imports, has, on the contrary, lowered customs duties on a range of imports. To claim under these conditions that the proposed step-up in capital expenditure will boost employment to any significant extent, is sheer chicanery.

What is more, between the two ways of spending, through larger capital expenditure or larger social expenditure, since the former is more import-intensive, it will only worsen the balance of payments problem toward which the country is headed. India’s export growth has suffered because of the world recession, despite a massive depreciation of the rupee; and the current account deficit for the latest quarter for which we have data has been in excess of 4% of GDP. The government could have killed at least three birds with one stone if it had increased social expenditure, instead of boosting capital expenditure: that would have directly improved the people’s lot; would have boosted employment to a far greater degree; and would have kept the balance of payments current deficit in check. Instead, it chose an option that is patently much worse.

So far, I have only compared two options before the government, arguing that it chose the worse one; but, of course, the government is not confined just to these two options. The ratio of government revenue to GDP, according to the government’s own estimates, is likely to remain unchanged next year compared with the current fiscal year. But the fact that there has been a massive increase in income and wealth inequality is well-known, and in a period of rising inequality, even in the absence of a wealth tax, the ratio of tax revenue to GDP should show an automatic increase; with a wealth tax or other revenue-raising efforts at the expense of the rich, this should be even more pronouncedly the case. What is remarkable about the budget is the absence of any serious revenue-raising measures.

The budget, of course, has provided income tax relief to certain segments of the salaried classes; but its myopia in two senses is quite amazing: one, its utter indifference to the need to raise government revenue as a proportion of GDP in a period of sharply increasing income and wealth inequalities; and two, its utter indifference to the need to provide larger social expenditure which could boost purchasing power with the working people and its emphasis instead on capital expenditure whose employment generating effect largely leak out abroad.

To call this budget myopic, however, as I have done, is perhaps to miss the point. The infrastructure sector is where its “crony capitalists” have a special interest; spending on the infrastructure sector, therefore, is a way of helping its “cronies”. And this particular government, on its past performance, can hardly be expected to put the interests of the economy as a whole, let alone those of the working people, above the interests of its crony capitalists.

(Prabhat Patnaik is Professor Emeritus at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Courtesy: The author’s blog at networkideas.org.)