This is a condensed version of the lecture by professor Vijaya Ramaswamy, titled Reluctant Brides, Deviant Wives and Cunning Witches: Women in Tamil Mahabharatas, focusing on Draupadi, Alli and Aravalli-Suravall.

The event was scheduled to be held at the C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research, in Chennai, on January 4, 2020.

❈ ❈

The critical editions of the Mahabharata are authored by men, Brahmanical in outlook, if not in fact, and located squarely within the patriarchal register, or framework. These tend to freeze women within certain descriptive and prescriptive frames contained within the Sanskritic-Brahmanical and patriarchal register.

Regional variations of the Mahabharata, on the other hand, are much more fluid in their portrayal of the epic characters. Personalities like Duryodhana and Karna, represented in negative terms as ‘evil’ forces, find a more nuanced and less biased space within the regional versions.

This is especially true of the women protagonists within the epic like Draupadi, Gandhari and Karna’s wife, Ponnaruvi.

Ponnaruvi’s name does not figure in the critical edition which talks instead of Vrushali (the daughter of Duryodhana’s charioteer) as Karna’s wife. In contrast to the low social status of Vrushali, in the Tamil rendition of Karna’s life, Ponnaruvi is said to be of royal descent, a Kalinga princess.

The availability of books in the Madras Presidency in the course of the 19th century brought the Mahabharata to the commoners, both men and women.

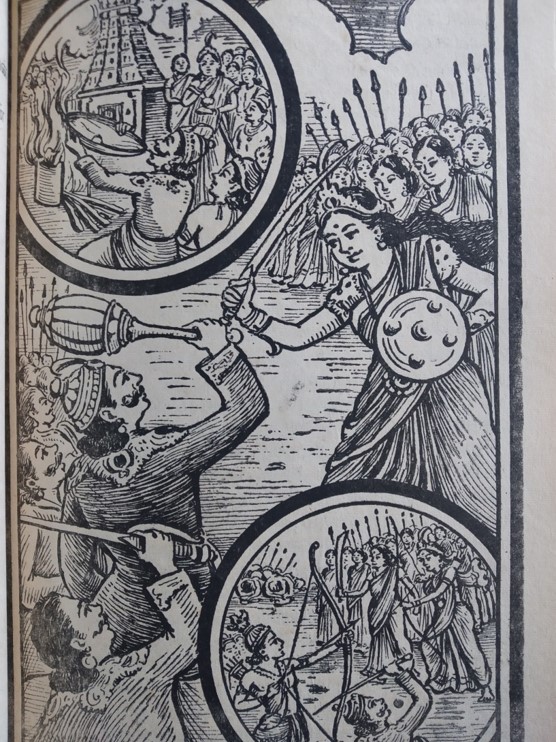

Cheaply priced popular folklore called ‘gujili’ literature (which refers to Gujarati merchants) entered the market, gaining a new readership, especially among women. Fragments from the Tamil Mahabharatas, with additions and interpolations, or even beyond both, with totally new protagonists, changed the understanding of characters from the Mahabharata, bringing into focus the anti-heroes and the militant, non-conformist women who were either from the margins of the epic or outside it altogether.

It is clear that in the Tamil versions of the many fragmented Mahabharatas, one finds a re-invention of the epic, centre-staging women who sometimes find a place in the critical editions, like Draupadi, and also those who sometimes do not find a place in them, like Alli Arasani, although she probably features in the Sanskrit edition as Chitrangada.

As Simon de Beauvoir puts it, “women’s folklore researched by women makes the women in such studies ‘truly subjects rather than objects.’

This exploration into the Tamil Mahabharatas is an attempt to contextualise the process of transmission and transmutation of narrative fragments from the great epic that may have had their birth in the non-Sanskritic, perhaps, to some extent, matri-local, early Tamil society. The myths of warrior queens like Alli, Pavzhakkodi, snake princess Ulupi and the Siva devotee Minnoliyal, and their marriage to Arjuna, a leading protagonist of the Mahabharata, break the mega-narrative of a great epic, bringing centre-stage figures who are wholly absent in the mainstream version (Vyasa’s Mahabharata).

Ballads like Ponnaruvi Masakkai, Karna Moksham and Karnamaharajan Chandai draw attention to the narrative of Karna’s wife Ponnaruvi whose hatred of her so called ‘low-caste’ husband and her unwanted pregnancy, brings into sharp focus issues of both caste and class.

Karna, before his death on the 17th day of the Kurukshetra war, reveals the secret of his birth, turning her repulsion into regret. These fragmented narratives can therefore be said to constitute significant regional variants of a grand narrative, irrespective of whether they truly constitute counter-narratives or get socialised into the patriarchal mainstream.

It is only among the Tamils that Draupadi is venerated as a goddess and there are around 300 temples dedicated to Draupadi or Panchali Amman all over Tamil Nadu.

In my research into the Tamil Mahabharatas, the portrayal of the characters of Kunti, Gandhari and Draupadi in the critical editions have been juxtaposed against the more fluid representations, especially of Draupadi, in the regional retelling of the Mahabharata such as the celebrated Tamil text, S. Subramanya Bharatiyar’s Panchali Shapatam.

Equally important in the re-telling of Draupadi’s character and role are performance texts such as Draupadi Kuram or Kuravanji.

It is noteworthy that the deification of Draupadi by Tamil communities has evolved in the course of a few centuries into the Draupadi Amman cult. Similarly, Gandhari is also worshipped as a goddess by many Tamil castes.

Professor R. Srinvasan, in his introduction to Nallapillai Bharatam, has opined that it is the Draupadi cult which is responsible for the rapid spread of the Mahabharata, especially in the narrative and the performative mode.

The ritual of fire-walking is practised in the festivals celebrated around both Draupadi and Gandhari Amman among the Tamils, not only in India but wherever the Tamils have settled as a sizeable diasporic community – in areas such as Fiji and Reunion islands.

There are three major components of the Draupadi festival celebrated all over the Tamil region and more particularly in its northern part – the Mahabharatam recital every evening by the Bharata Prasangi (artists who present a dramatised narration of the Mahabharata); the folk form of Bharata koothu, also called theru koothu, literally street performance, which are all-night performances based on the epic; and tee midital, or fire walking, as an act of worship dedicated to Draupadi Amman. Very often the Kootandavar festival, which is about the story of Aravan, the son of Ulupi and Arjuna, is conjoined with the Draupadi cult ritual festivities.

In addition, the texts, Alli Natakam and Alli Arasani Malai, which connect with the Mahabharata, are read both as texts, largely by women, and also performed as theru koothu or villu pattu, a narrative performance accompanied by a huge bow-stringed instrument called ‘villu’.

Alli is said to be the only child of Malayadvaja Pandya, a king who is not located in chronological time. The location of the Alli myth in Madurai, the capital of the Pandyan kingdom, seems deliberate in view of the hagiographical tradition enshrined in the Tiruvilaiyadal Puranam, stating that Madurai was ruled by the three-breasted Meenakshi.

It is said that Alli’s was a miraculous birth since she was found on an ‘alli’, or flower, at the conclusion of the performance of the ‘putra kameshti yaga’, a sacrifice performed to beget a child. Like the divine ruler Meenakshi, Alli too was trained in the martial arts and went to a ‘gurukula’ (traditional school) to learn the sacred texts as well as the texts of governance.

Alli began her political career by defeating Neenmugan, the usurper of the Pandyan throne, in battle and was crowned ruler. The ballad Alli Kadai says that Alli defied the tyrant and successfully led the army against him, and Madurai itself acquired fame and glory because the valorous Alli destroyed the tyrant Neenmugan.

She governed with an all-woman establishment. Hence the popular Tamil saying ‘Alli Rajyam’ for a household dominated by women.

The Alli Arasani Maalai says:

If you take the name of Alli

Even the bird will not sip water

If you take the name of Alli

The goblins (Ganas) will dance.

If you take the name of Alli

The decapitated head will chatter!

The Alli narrative connects with the Mahabharata epic when Arjuna becomes attracted by Alli and marries her by stealth, resulting in the birth of Pulandiran.

In the critical Sanskrit edition, Alli’s story has a parallel with Chitrangada and her son Babruvahana. From this turn in the Alli story, it gets tamed into a patriarchal narrative when it enters Tamil stage and cinema since the audience was largely a male audience.

Yet, as a text Alli Kathai was read extensively by women and was seen as a deviant text.

Neelambikai Ammaiyar, the daughter of Maraimalai Adigal (co-founder of Tani Tamizh Iyakkam, or the pure Tamil movement, started in 1916), wrote:

“Women should not be permitted to read texts like Alli Arasanikkovai Pavalakkodi Malai, Eni Etram etc., which may lead them into bad ways. They do not only read such texts day and night but also read books (Brahmanical Sanskrit texts) like Kaivalya Navaneetam which are false doctrines.”

On the one hand, Neelambikai Ammaiyar’s statement indicates the patriarchal responses to the Alli myth which was regarded as corrupting and subversive. At the same time, her fears prove that women read these Mahabharata fragments, centred on women, avidly.

To conclude, the Tamil Mahabharatas, whether as textual fragments or as performances, break caste and gender barriers in significant ways, marking a departure from the Sanskrit Mahabharata epic. In their manifold forms they represent different strokes in the Brahmanical patriarchal narration.

(Professor Vijaya Ramaswamy, formerly at the Centre for Historical Studies, JNU, is currently Tagore Fellow at the IIAS, Shimla. Courtesy: The Wire.)