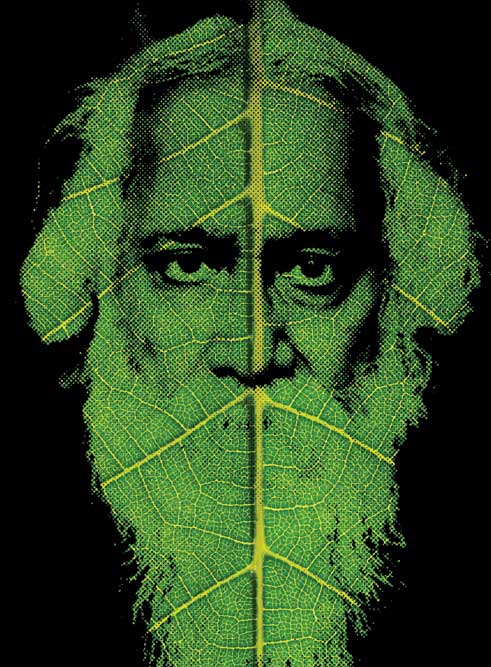

In 1922, Rabindranath Tagore published one of his most important works, the play Mukta-Dhara. The story, rich in symbolism, is a simple yet powerful one.

A child of mysterious birth is found abandoned by a mountain waterfall. He is adopted by the royal family and raised as the crown-prince, Abhijit. As he turns into a young man, Abhijit continues to feel close to the falls. He eventually learns that he is not a prince by birth. He discovers a spiritual kinship with the falls. He goes and sleeps below the waterfall at night. When asked by his father, King Ranjit, why he does something so outlandish, he replies, “In the sound of this water, I hear my mother’s voice.”

The king has other designs on the mountain stream. He appoints an appropriately named figure, Yantraraj Bibhuti, a famous, pompous engineer, to construct ‘a machine’ to build a dam across it. Those building the dam sing an anthem to the machine, chanting, ‘Namo yantra, namo yantra.’ When told about the damage from the new dam to the fields of peasants in the valley below, Bibhuti boasts that “the purpose of my dam was that human intelligence should win through to its goal, though sand, stone and water all conspired to block its path. I had no time to think of whether some farmer’s paltry crop of corn would die.” He lacks the heart to consider the ‘collateral damage’ that the execution of his technocratic ambition brings. He is captivated by the old dream of what digital business commercials today call ‘building a smarter planet’.

All this upsets Abhijit immensely and he joins the protesting villagers of Shivterai, the valley of villages which is denied water after the dam comes up. The king is also interested in getting the dam built since it would enable him to dominate better the villagers in the Shivterai. He has his son arrested, but the villagers set him free. The dam is completed. However, one night Abhijit breaks open the dam at a weak spot. The released torrent of water carries him away. In the cause of defending the waterfall and the people, he willingly sacrifices his life. In the end, he is united with the waters that bore him and even the king is forced to acknowledge regretfully that “in her freedom he has found his own!” Humanity and nature are united at last. In Abhijit’s visarjan (sacrifice through immersion and drowning) is also his mukti (freedom).

Among the many questions that Rabindranath prompts the reader to ask through such a vivid story, perhaps the most important, and readily forgotten one relates to the matter of human freedom and the intimately related spiritual and ecological conditions under which it truly obtains. What is the relationship between nature and the free spirit? Are we not in denial of our own spirit when, mesmerised by the vast, global man-made artifice in which we live, we altogether fail to notice our inevitable roots in the natural world? Isn’t the rediscovery of the spirit essential to the recovery of an imperilled earthly ecology? Can human society ever be free unless ‘nature’ is, in some subtle complementary sense, also free? If the waters in the rivers are instrumentally impounded, drowning rainforests in the bargain, what does it say about a society founded on such ecological violence? Is it not a delusion for it to regard itself as ‘free’ when it is premised on structural avarice? Power is hardly the same thing as freedom. Rabindranath makes one of his protagonists in the play, the king’s uncle, Visvajit ask his nephew at the religious festival held to consecrate ‘the machine’ built by Bibhuti to dam the stream: “God pours out his water freely for all, for every thirsty soul on earth. Why have you blocked the stream?” A question we are surely entitled, as citizens of a putatively free country, to ask those elected to office.

Interestingly, Rabindranath wrote this play just when the world’s first mass protest against large dams was taking place in Maharashtra. (It is not clear if he was aware of this fact). Between 1920 and 1924, a veteran Gandhian leader, educated in England, Senapati Bapat led a large number of peasants in the famous Mulshi Satyagraha against a dam that the Tatas were building on the Mula river in the Sahayadri mountains of Maharashtra. Bapat and other leaders of the movement were imprisoned by the British Government. The Mulshi dam was built and continues to supply water and electricity to Pune and Mumbai to this day. This is one of the oldest modern dams in India.

Mukta-Dhara has proved to be prophetic in that it presages the future of development in India over an immensely eventful hundred years. Rivers have suffered one insult after another in Independent India. Rivers constitute the circulatory system of the earth. They are to the earth what the bloodstream is to our bodies. To repeatedly build large dams across them is much like inserting giant artificial stents across the network of our veins and arteries to convert the human body into an efficient blood bank.

While inaugurating the Bhakra Dam in Punjab in 1954, the nation’s first Prime Minister had taken recourse to a religious metaphor and described large dams as “the temples of modern India”. However, within just four years, while speaking to an audience of irrigation engineers, Nehru himself, in a rare moment of developmental regret, referred to the “disease of gigantism” that had gripped India. Today, this gigantism is a national pandemic and takes the form not just of large dams like Sardar Sarovar, Pancheshwar and Polavaram, but of oil refineries (the world’s largest one planned in Konkan, threatening 17 villages and 2 million mango and cashew trees across 15,000 acres), impressive airports, expressways, shopping malls and the like.

Dam-building yields high returns in the short run to builders, developers, and their government patrons. We do not ordinarily hear about this. Nor do our governments share information on communities uprooted, numbers of families displaced, livelihoods and forests destroyed. What reaches our ears are the official justifications for ambitious projects couched in the language of the purported public benefits of large dams in terms of energy and water. In the long run, such an approach to questions of energy and water can only be disastrous. Recent reports suggest that thanks to diminished water released from the Sardar Sarovar Dam, the ingress of the Arabian Sea into the Narmada river estuary near Bharuch could be as much as 72 km, putting in jeopardy thousands of hectares of arable land due to salinisation. The irony ought not to be missed: farmers in this region of Gujarat were meant to be among the intended original beneficiaries of the Narmada project.

At a deeper level, Mukta-Dhara also foretells the manner in which people across the country, despite repeated protests, have been losing their freedom— those uprooted by development quite obviously so, those ‘benefitting’ from it (mostly living in cities) more subtly and invisibly. In its hunt for water and energy, rapidly industrialising metropolitan India has built well over 4,000 large dams during the last ten decades, uprooting the lives of an estimated 40 million people, though the actual figure is perhaps higher. Can those who have lost their way of life in such upheavals, their healthy habitat, their communities, their livelihoods, perhaps in exchange for the compensation of an insecure ‘job’ they may not have liked even if it sometimes yielded more cash in hand, be said to be ‘free’? And how are we to judge the freedom of those like ourselves who were born—ecologically estranged from birth—in urban or metropolitan India, where the air we breathe and the water we drink is more contaminated by the day? This is the ecologically fatal price of ‘progress’. Rabindranath anticipates much of this, not only in the play, but in many essays, lectures, letters, poems and stories.

The Blind Spot of Modern Political Thought

Political philosophers and social scientists usually think about freedom— or even liberty—independent of the ecological context in which humanity lives. A utilitarian calculus is blithely assumed in the background of these discussions. Some of the natural preconditions of liberty and human well- being—climate stability, sufficiency of clean air and water, to remind ourselves of the obvious—are taken for granted in most political discussions. Needless to add, the enormous spiritual meaning of the natural world is repressed out of human awareness.

By contrast, in virtually all his creations and utterances, Rabindranath never loses sight of this salient fact. Where others see mere soil or water resources, the poet notices the soul hidden in our relationship to the elements. In his important work for modern readers, Sadhana, he writes: ‘The man, whose acquaintance with the world does not lead him deeper than science leads him, will never understand what it is that the man with spiritual vision finds in these natural phenomena. The water does not merely cleanse his limbs, but it purifies his heart; for it touches his soul. The earth does not merely hold his body, but it gladdens his mind; for its contact is more than a physical contact—it is a living presence.’ These are not the poetising excesses of a raving mystagogue. They are the calm, sober reflections of a spiritually illumined mind.

The metropolitan, modern world has come to dwell in a matrix of habits which must meet the stressful demands of a complex, highly processed man-made environment, as removed from the natural world as it is possible to imagine, in effect enforcing a default regime of conformity to a realm of abstractions, both mental and physical. Think of the security equipment one has to negotiate at stations, airports and all public institutions nowadays, as also of the many passwords one must remember to navigate cyberspace just in order to manage one’s credit card or bank account. In order to facilitate the smooth operation of the money machine of the global economy, our lives have become thoroughly alienated from any living link to the natural world.

Do we have the privilege of such convenient abstraction anymore? The fact that we may now be living in what geologists term ‘the anthropocene’ prompts the fundamental question: what will remain of liberty if humanity in significant parts of the earth is overwhelmed by climate events in a now foreseeable future? In such a predicament, will we still be discussing, by lazy habit, things like citizenship and individual rights? Or wouldn’t the potentially catastrophic turn of events (even much more frequent wars) force us to think in a meaningful and imaginative way about collective rights, with the help of which communities that still live in underprivileged parts of the world, in relative intimacy with nature, may be in a better position to protect the habitats, crafts, cultures, and languages that have long sustained them? Is there any well-founded hope for the cities unless the rural cultures of this land are ecologically renewed, unless the last people on earth who know something about living sustainably and creatively with nature have a chance to keep their way of life? Blind to much that should be obvious, there are over 800 million Indians in the villages of India who our governments want to urbanise. There aren’t quicker roads to ecocide.

If India is turning into a voracious ‘graveyard of languages’, as the famed linguist Ganesh Devy has frequently drawn attention to, surely the reasons for this lie in the familiar ecological violence of modernity and development? Devy has argued, for instance, that hundreds of Adivasi tongues have disappeared because of the government’s insistence on the modern idea that a language, in order to be recognised as such, has to have a written script (this, when, as Devy points out, languages have far more variety before they are written down). Many more languages have disappeared because entire modes of socio- economic life have been rendered obsolete or impossible on account of ‘development’.

If communities of fisherfolk and pastoralists have lost their languages, cultures and communities, it is because the elite-driven technocratic processes of development and modernisation have rudely pushed them out of their habitats, colonising them with an avarice all too structural and predatory. In arrogant negligence of all the accumulated knowledge of the life-sciences, earthmovers have taken the place of earthworms. Is it so difficult to imagine what this will ultimately do to the soils so desperately needed to provide for ten billion human stomachs?

In the modern world, such violence is routine. Whether a country is democratic or not, these are not ecological injustices that can be redressed with narrow notions of individual rights. We are in need of an entirely different imagination which draws at least a significant part of its cultural and spiritual inspiration from the natural world and the communities that still in relative contact with what modern civilisation would rather cast out of contention as ‘the wilderness’.

An environmentalism in which nature becomes a token afterthought to the economy, which habitually takes facile exemptions from geography (and history), turning real places into portable, exchangeable abstract spaces, and whose foundations are not allowed to be questioned, can only serve to temporarily ‘greenwash’ self-destructive growth. In the long run, the damage will not be possible to correct—for the sort of problems we are discussing here are well ahead of us, and perhaps not clearly visible from the road being travelled. Technological opacity brings structural ecological idiocy with it. We are at that critical point in human history when the cumulative consequences of possibly runaway climate change and the rapid deterioration of vital ecosystems across the earth are spinning so rapidly out of human control as to put our species survival itself in question. What then of actually existing democracy? Is it even democracy, properly speaking?

Are Democracies Really Free?

The real question is whether we can still afford the shallow notions of human liberty which are themselves responsible in no small measure for the precipitation of such a state of affairs. There is perhaps nothing more dangerous than illusions of freedom. And—regardless of the fact that social science usually pays little attention to it—we may have been enticed into an operative definition of liberty more akin to licence than to freedom. This, in fact, might be necessary to condition human cognition in such a manner as to turn us into restless consumers.

Those who live under obvious despotism or a brutal dictatorship know palpably the cage they live in. Citizens of totalitarian consumer democracies are twice unfree for occupying invisible—now digitised— cages. We may seem to enjoy all the official liberties, such as free—if ineffective— speech (though today even that faces threats everywhere). But our spirit is mired in a morass of often unspeakable oppression brought on by fears sustained by own collective greed (which serves the interests of gluttonous global corporations) as well as the hidden eye of an Orwellian State.

After visiting America, the French traveller Alexis de Tocqueville had prophesied such a predicament with chilling accuracy almost two centuries ago:

I seek to trace the novel features under which despotism may appear in the world. The first thing that strikes the observation is an innumerable multitude of men, all equal and alike, incessantly endeavouring to procure the petty and paltry pleasures with which they glut their lives. Each of them, living apart, is as a stranger to the fate of all the rest; his children and his private friends constitute to him the whole of mankind. As for the rest of his fellow citizens, he is close to them, but he does not see them; he touches them, but he does not feel them; he exists only in himself and for himself alone; and if his kindred still remain to him, he may be said at any rate to have lost his country.

Above this race of men stands an immense and tutelary power, which takes upon itself alone to secure their gratifications and to watch over their fate. That power is absolute, minute, regular, provident, and mild. It would be like the authority of a parent if, like that authority, its object was to prepare men for manhood; but it seeks, on the contrary, to keep them in perpetual childhood…For their happiness such a government willingly labours, but it chooses to be the sole agent and the only arbiter of that happiness; it provides for their security, foresees and supplies their necessities, facilitates their pleasures, manages their principal concerns, directs their industry, regulates the descent of property, and subdivides their inheritances: what remains, but to spare them all the care of thinking and all the trouble of living?

After having thus successively taken each member of the community in its powerful grasp and fashioned him at will, the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting. Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannise, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.

I have always thought that servitude of the regular, quiet, and gentle kind which I have just described might be combined more easily than is commonly believed with some of the outward forms of freedom, and that it might even establish itself under the wing of the sovereignty of the people.

Such is the condition of today’s famed democracies in which even citizens of privilege move around in a digital daze, in a state of perpetual suspicion, yet all too often unmindful of the fact that they are under the ceaseless surveillance of the State and the Corporation. Under such conditions, freedom can be but a fragile belief, subject to forces the individual may hardly suspect. The tragic element in this solipsistic, Kafkaesque arrangement is that isolated individuals all too often become a party to their own unfreedom. One significant consequence of this is that they toss between the devil of suspicion and the deep blue sea of gullibility. The harvest is reaped by a predatory media, the strange thing about which is that virtually everyone thinks they are not fooled by it and yet are often led to believe it because they pridefully believe that everyone except they themselves believes it.

Listening to Rabindranath

Among many others, on various continents, Rabindranath Tagore anticipated in broad outline, a century ago, the onset of authoritarianism in the Western world. On a visit to America, he noticed that people there believed themselves to be free, but this was in fact very far from being the case. Nor, in his view, was this atypical of the modern world. He wrote to his close friend CF Andrews: ‘The freedom of unrestrained egoism in the individual is licence and not true freedom…The idea of freedom which prevails in modern civilisation is superficial and materialistic. Our revolution in India will be a true one when its forces are directed against this crude idea of liberty.’

Fatally, it is precisely ‘this crude idea of liberty’ which has triumphed in the world after World War II, and especially after the end of a bipolar world a generation ago. Consumer modernity in the digital era builds precisely upon this crude idea of liberty which inevitably brings us an ever more imperilled world as the planetary ecological crisis worsens.

That harmony in the human relationship to the natural world is a prerequisite to human freedom is a theme that recurs throughout Rabindranath’s writings. To him, an intimate kinship with our natural surroundings is essential to realise ourselves as a free, illumined humanity. It is nature which inspires ‘song, art, beauty’, in the absence of which ‘the soul is denied nourishment and remains neglected and starved’ and it becomes really difficult to ‘bear our sorrows’. We are normally unconscious of this great need, and often realise it only once it is attended to. While he was looking after his family estates in East Bengal (now Bangladesh), in sylvan surroundings, and was living on a boat on the Padma river, he wrote to his niece: “People cannot even begin to believe that things like these are absolutely essential for anybody. I too slowly begin to forget that almost none of the roots that feed myself are getting any nutrition. In the end, when suddenly one day some little source of nourishment becomes available, and I feel the intensity of my eager heart, I remember that all these days I was starving, and that this is an essential requirement . . .”

We do not have to accept Rabindranath’s piercing critique of the modern idea of liberty and his ecological notion of freedom. We may merely consult the price list of any real estate dealer in the city where we live. Between two otherwise identical apartments in any building, the price of the one which looks onto a freshwater lake, a wetland or a forest would be predictably higher than the one that instead faces a neighbour’s store-room. In other words, we are all willing to pay a premium to experience natural surroundings which offer nutriment to the soul. We are merely unaware of the full meaning of this for our inner selves. It is to this that Rabindranath wishes to draw the attention of the modern mind, which he believed was normally too intoxicated with power to realise the simple truth of freedom and the conditions under which it obtains.

(Aseem Shrivastava trained as an environmental economist at University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He taught philosophy at the Nordic College of Norway and currently teaches courses in Ecosophy at Ashoka University. He devotes much of his time to working as an independent researcher and communicator of issues relating to ecology and modernity. He is co-author of ‘Churning the Earth: The Making of Global India’. Courtesy: Open, a weekly current affairs and features magazine.)