It is well known that indirect taxes fall disproportionately on the poor, and therefore a tax regime that relies mostly on such taxes is both unjust and inefficient in terms of not mopping up the excess profits and incomes of large corporations and rich families. The Indian tax system has always been broadly regressive, with an inordinately high share of indirect taxes, even when compared to countries at similar levels of per capita income. But the extent to which this reliance has been accentuated during the Modi government are not fully appreciated. When combined with other regulatory measures and public policies that have greatly increased the market power of some large corporates in particular, the system has greatly added to the process of making India one of the most unequal countries in the world.

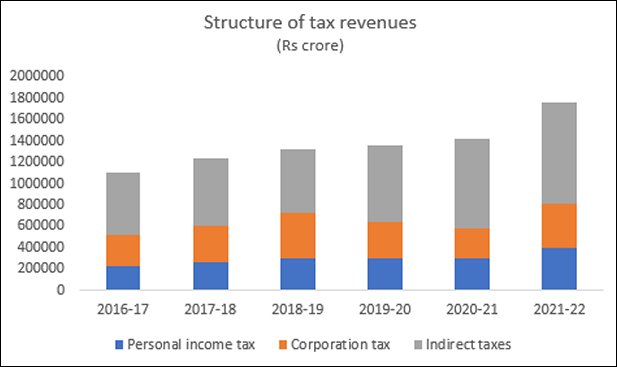

Chart 1 describes the overall composition of central government tax revenues, and shows that indirect taxes have generally accounted for more than half of total tax revenues. Indeed, the ratio has worsened in recent years, with indirect taxes going up from around 51 per cent of total tax revenues in 2016-18, to as much as 59 per cent in 2020-21 and remaining high at 54 per cent in 2021-22.

The direct tax regime is certainly lacking in many ways, with the abolition of wealth taxes and negligible inheritance taxes, despite the clear evidence of extreme concentration of wealth in a few hands. Despite much noise made by the Prime Minister and others about bringing back “black money” salted away abroad and forcing offshore assets to be declared and taxed, very little has actually been done for this. The Indian government has received at least some information about assets of Indian citizens held abroad, yet it has neither pursued this systematically, not allowed the lists of such individuals to be made public. This lack of transparency and inaction enables wealthy individuals to continue to prosper while most of the people face extremely dire economic conditions.

However, it is in the matter of corporate taxation that the upward bias of the government has become particularly evident. Chart 2 shows the recent pattern of revenues from corporate taxation. It is particularly striking to note the dramatic decline in corporate tax receipts in both fiscal years 2019-20 and 2020-21. The recovery in 2021-22 appears good in contrast, but still leaves the share of corporate taxes in total taxes well below the levels of several years earlier.

This sharp and unusual decline in tax revenues was not only, or even dominantly, because of supposedly “God-given” external factors like the Covid-19 pandemic that battered the economy. Indeed, the first major decline occurred well before the pandemic, and was the result of the explicit decision in September 2019 to offer significant tax breaks to companies. The corporate tax rate was lowered from 24 per cent of 21 per cent and a variety of other fiscal sops were offered, with the supposed aim of generating more private investment in a context of economic stagnation. In the event, private investment did not rise but continued to fall in real terms, but the large corporates in particular happily pocketed the windfall gains from lower tax rates.

Chart 3 describes the impact this had on corporate tax collection, seen in quarterly terms. Since September 2019, corporate tax revenues remained low and declined sharply in some quarters. This has been ascribed to the impact of a slowing economy, especially during the extreme lockdown in the first phase of the Covid-19 pandemic. But in fact, corporate taxes declined even in the periods when aggregate income and corporate profits were growing.

This becomes clear when the actual evidence on corporate profits over this period is examined. The RBI provides data on the financial performance of non-government non-financial public limited companies, based on the audited annual accounts of 7,233 companies with a total paid-up capital of Rs 5,40,493 crore of at end-March 2021. The results in terms of profits and tax payment for these companies, in the period 2016-17 to 2020-21, are presented in Figure 4.

The contrast between the trends in profits and in tax payments by these same companies is striking. (It should be noted that in the first two years described in Chart 4, tax payments exceeded profits of that year, probably because of arrears in tax payments and demands for previously unpaid taxes.) Tax expenses of companies declined sharply in 2018-19, and declined even further in the following year. Thus, between 2018-19 and 2020-21, the rate of taxes paid out of the recorded profits of these companies declined from 34 per cent and to 28.7 per cent.

Note that even this average can be misleading, as it has been found that the incidence of corporate taxes is also unevenly distributed, with the large corporations (and multinational companies) paying much lower effective rates of taxation than middle and small companies. It has been estimated that some of the largest corporations pay very low, almost negligible taxes even when they experience very high profits, because they are able to utilize various loopholes in the tax regime to their own advantage. For example, one of the largest corporate behemoths in the country, Reliance Industries Limited owned by Mukesh Ambani, is estimated to have paid an effective tax rate of only 3.1 per cent in 2020-21, a year when its profits increased by 35 per cent. (https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/companies/decoding-reliance-inds-3-effective-tax-rate/article34916732.ece)

The inability or unwillingness to collect taxes from large corporates and rich individuals has several adverse consequences. It is one of the main reasons why people in the country continue to suffer from inadequate public services, why state governments suffer from a real financial crunch that prevents them from meeting basic obligations to their citizens, why the government’s macroeconomic policy is so conservative and procyclical to the point that it cannot effectively counter downswings and shocks that adversely affect peoples’ lives and livelihoods. The demand for a more progressive and just tax system is therefore an essential part of a progressive economic agenda.

(C. P. Chandrasekhar was Professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Jayati Ghosh is Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA. Courtesy: Ghosh’s blog at networkideas.com and Business Line.)