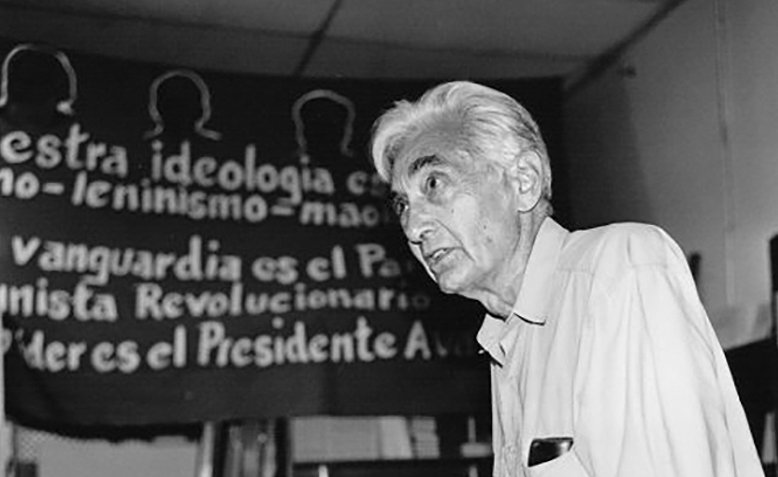

Being denounced by Donald Trump is a badge of honour for anyone on the left. Two years ago while he was still in the White House, the President took aim at one of the great icons of the US dissident tradition: “Our children are instructed from propaganda tracts, like those of Howard Zinn, that try to make students ashamed of their own history”. As part of his unhinged alt-right agenda, Trump was objecting to Zinn’s lifelong commitment to dispelling the myths that the US capitalist state has promoted over the centuries about its origins, operations and objectives.

Zinn was an exemplary socialist activist and intellectual who participated in many of the great struggles of the labour movement in the twentieth century. His greatest legacy is the book he published in 1980, A Peoples History of the United States, which remains the best overview of the country’s story from the viewpoint of the oppressed. Zinn brilliantly succeeded in his stated aim of exposing how the US has evolved into the most powerful oppressive force in history, brutally exploiting both its own population and those of many other countries:

“What struck me as I began to study history was how nationalist fervor–inculcated from childhood on by pledges of allegiance, national anthems, flags waving and rhetoric blowing–permeated the educational systems of all countries, including our own. I wonder now how the foreign policies of the United States would look if we wiped out the national boundaries of the world, at least in our minds, and thought of all children everywhere as our own. Then we could never drop an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, or napalm on Vietnam, or wage war anywhere, because wars, especially in our time, are always wars against children, indeed our children.”

First lessons

Howard Zinn was born into a Jewish working class family in New York a hundred years ago. Both his parents were part of the great waves of immigration that came to the US from Europe in the late nineteenth century. His father was born in the Austrian Empire and his mother in the Russian. They both encouraged young Zinn to be active in the trade union movement and to be a voracious reader. These two activities would become the pillars of his existence for the whole of his life. In the 1930s, as the Great Depression slammed into working-class neighbourhoods, Zinn had his first encounter with the hired prizefighters of the state. He attended a protest against austerity in Times Square and was smashed over the head by a police truncheon:

“From that moment on, I was no longer a liberal, a believer in the self-correcting character of American democracy. . . The situation required not just a new president or new laws, but an uprooting of the old order, the introduction of a new kind of society—cooperative, peaceful, egalitarian.”

High-altitude horror

Zinn found work as a shipyard worker in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and threw himself into the great labour struggles of the era as Roosevelt’s New Deal empowered union confidence and membership. He accepted the anti-war standpoint of the US revolutionary left at the start of WW2 but an intense detestation of fascism led him to join the USAF as a bombardier. This experience would be a major turning point in his life. Thousands of miles up in the air, Zinn and his crewmates had no awareness of the appalling carnage being inflicted on civilian populations by the American and British saturation bombing of Europe. After the war, however, when he visited the locations, Zinn was shocked and repulsed by the gratuitous slaughter condoned by so-called democracies.

He discovered that one of his missions, over the French town of Royan, had involved the first ever deployment of napalm, killing one thousand French civilians and many German soldiers who had already surrendered. Zinn was passionate about fighting fascism but his military experience brought home to him the true nature of the global capitalist system. It also turned him into a fierce anti-war activist for the rest of his life and would drive his opposition to later American interventions in Vietnam, Latin America and Iraq:

“There is no war of modern times which has been accepted more universally as just. The fascist enemy was so totally evil as to forbid any questioning. They were undoubtedly the “bad guys” and we were the “good guys,” and once that decision was made there seemed no need to think about what we were doing. But I had become aware, both from the rethinking of my war experiences and my reading of history, of how the environment of war begins to make one side indistinguishable from the other.”

Past and present

The Truman administration’s postwar GI Bill enabled Zinn and thousands of other services personnel to acquire a university education. He studied History at New York University and progressed to postgraduate level work, writing a pioneering thesis on coalminers’ struggles in Colorado. Remarkably, as a white male northerner, Zinn’s first teaching job was at an all-black women’s college in Georgia. It was typical of him to be more interested in educating those on the margins of society than the traditional academic elite.

This was in the early 60s when the US civil rights movement was starting to gain traction. Zinn’s conviction that History is a subject as much about the present as the past brought him into conflict with the conservative authorities at the college and prompted his dismissal in 1963. They did not approve that he was encouraging his classes to attend meetings of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as part of their homework!

Zinn and Zen

After this, he secured a post at Boston University where he taught till his retirement in 1988. Zinn was a charismatic and popular teacher whose lectures were often standing-room-only as he became a beacon for the insurgent social movements of the 1960s and 70s. Many of his students testified that his influence was decisive in helping them understand how racism, sexism and imperialism have been hardwired into American society from the very beginning. One of them was George Binette:

“I soon came to appreciate that through subtly weaving considerable erudition with personal reminiscence, he was challenging the received and often cherished assumptions about US history among young people. In person Zinn frequently projected a Zen-like calm. He seemed to possess exceptional patience, both for naive admirers and stridently reactionary critics, though he never concealed a zealous passion against injustice. And in contrast to many left-leaning academics, he combined his classroom stance with practical action.”

Not Neutral

A key part of Zinn’s massive appeal to students was how he practised his famous slogan that “You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train“. He would appear as frequently on demonstrations and picket lines as he would in lecture theatres. His anti-war credentials persuaded the North Vietnamese government to summon him to Hanoi in 1968 to oversee the release of three American POWs. When Daniel Ellsberg exposed the machinations of the Nixon administration in the Pentagon Papers in 1971, Zinn was one of the those entrusted with their publication. He acted as a crucial bridge between the Old Left of the Wobblies and the great labour battles of the 1930s, and the New Left of the 60s that was energised by civil rights and the Vietnam protests.

Theory and practice

This inspiring synthesis of theory and practice culminated in A People’s History of the United States which had sold two million copies by the time Zinn died in 2010. This remains the best text to start with for anyone looking to understand the reality of America’s rise to superpower status, beneath the jingoistic rhetoric of the likes of Nixon, Trump and Biden. From the genocide of the native population by white settlers to Reagan’s delusions of war in space, the book is a brilliant evisceration of the hypocrisy of the elite and celebration of the resistance that has come from below. Zinn summed up the philosophy that underpinned his view of US history:

“The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, most often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.”

Of course Zinn did not live to see a socialist revolution in America. However he never gave up hope that his students might live to see it and was happy to be part of acts of resistance at every opportunity. As he wrote:

“The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvellous victory.”

(Sean Ledwith is a Counterfire member and Lecturer in History at York College, where he is also UCU branch negotiator. Courtesy: Counterfire, a socialist organisation and website in the United Kingdom.)