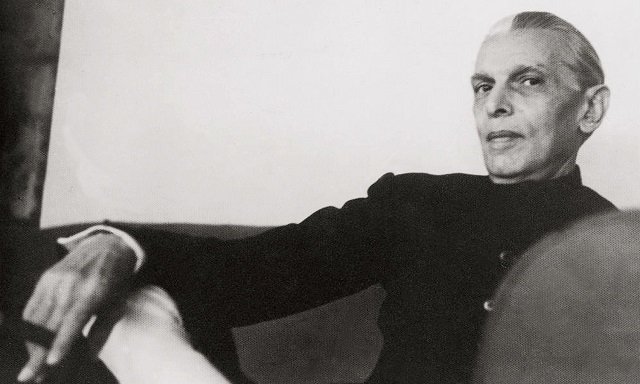

The Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) is not just a place of learning. It was in the forefront of a movement for the demand of Pakistan and still leans towards what is considered beneficial to the millat. A photo of Mohammad Ali Jinnah on the wall of Kenney Hall, the most prestigious place in AMU campus, is no surprise. It was there even before partition and it continues to be there all these years. But what amazes me is its disappearance on May 1 and reappearance on May 3!

True, it was the handiwork of a fanatic BJP member. But he should retract his steps within two days and put back the photo where it had hung since the time before partition looks extraordinary. Perhaps the person concerned was admonished by the BJP high command which is trying its best to woo Muslim voters at the Karnataka state election.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has also kept the polls in mind when he addresses different rallies in the country. Once in a while he tends to make remarks like there should be electricity at cremation grounds as is the case at burial grounds. But this is to assure the Hindu audience that the BJP has not strayed from the party’s philosophy of Hindu Rashtra.

No doubt, the majority of Hindus—they are 80 percent in India—tilt towards what is known as Hindutva. But I do not think that this is something long lasting. Hindus and Muslims have lived together for centuries. They would continue to do so despite the hot winds of Hindutva blowing at present. By temperament, India is a pluralistic society. It would stay that way although at times it looks like going the Hindu way; there always a spoil-play group which opposes everything worthwhile for the sake of opposition.

Take the case of India-Pakistan relations. There are elements which are bent on negating every effort towards conciliation and rebuff steps that help promote good relations between the two countries. Some years ago, the Pakistanis themselves took the initiative to rename the Shadman Chowk in Lahore and the gesture was very much appreciated in India. In fact, the renaming of the chowk gave birth to the idea of honouring heroes of the pre-partition days.

I recall that after celebrating Bhagat Singh’s birthday in March some years ago, a delegation of Pakistanis participated in a gathering at Amritsar in April to recall the Jalianwala Bagh tragedy which had Hindus and Muslims as martyrs. So much enthusiasm was created that preparations were afoot to hail the sacrifices of those who were part of the Indian National Army and the naval uprising in 1946. The two challenges to the British, even when the Hindus and Muslims were divided, indicated that when it came to a third party, both sides were willing to join hands to thwart it.

This is more or less what Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, had said when he came to the Law College at Lahore in 1945 when I was a student. To my question as to what would be the stand of Pakistan if a third power attacked India, he said straightaway that the Pakistani soldiers would fight by the side of Indian soldiers to defeat the enemy. It is another matter that military dictator General Mohammad Ayub Khan did not send any help to India when it was attacked by China in 1962.

Bhagat Singh was only 23 when he went to the gallows fighting against the British rulers. He had no politics other than the politics of sacrificing one’s life and freeing India from bondage. I was surprised to know that there were as many as 14 applications against renaming the Shadman Chowk. This was the same roundabout where a scaffold was erected to hang Bhagat Singh and his two colleagues, Rajguru and Sukhdev.

Jinnah’s name is associated with partition. Was he alone to blame? When I talked to Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, at his place in London in the early 90s, he said that then Prime Minister Clement Richard Atlee was keen that India and Pakistan should have something in common. Mountbatten tried for that but Jinnah said that he did not trust the Indian leaders. He had accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan which envisaged a weak centre. But India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru said that all would depend on the decision of the Constituent Assembly which was already meeting in New Delhi.

Differences between the two sides only accentuated with the passage of time. In the 1940s, when the Muslim League had adopted a resolution for the establishment of Pakistan, partition looked inevitable. Both sides were not facing facts on the ground when they rejected the idea of transfer of population. People themselves did it, Hindus and Sikhs coming to this side and Muslims going to the other side. The rest is history.

That was in 1947. Today, the Muslims in India, approximately 17 crore, do not matter in the affairs of India. True, they have the voting rights and the country is ruled by the Constitution which gives one vote to one person. But they have lost their say in decision making. What Maulana Abul Kalam Azad had said before partition has come true. He warmed the Muslims that they may feel insecure in the country because their number was small but they can proudly say that India belonged as much to them as it did to the Hindus. Once Pakistan was established, the Hindus would be able tell the Muslims that they have got their share and should go to Pakistan.

Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel were able to keep India pluralistic after partition. But the line drawn on the basis of religion is what haunts everybody today. The growing importance of BJP is because pluralism has weakened. Secularism needs to be strengthened so that every community and every part of the country feels that it is equal in the affairs of the country.

Email: kuldipnayar09@akshay