The global food crisis has now grown to such proportions that everyone is talking about it (even though world leaders are doing relatively little about it). It has become an article of faith to blame the war in Ukraine for the supply disruptions that have led to dramatic price increases in global food grain markets, which are now impacting food importing countries as well as poor populations across the world. Certainly, this war has been a catalyst for the recent spikes in food prices—but seeing that as the only cause is not just simplistic; it risks policy inaction to address some of the other factors, that can be controlled.

The latest Food Outlook for June 2022, just published by the Food and Agriculture Organization, repeats the concerns that are now being widely voiced. Because of “soaring input prices, concerns about the weather and increased market uncertainties stemming from the war in Ukraine, FAO’s latest forecasts point to a likely tightening of food markets and food import bills reaching a new record high.”

This assessment is almost entirely based on supply concerns: the shocks to global production and trade caused by the war between two important grain producers Russia and Ukraine; and the impact on prices of inputs, including fertilizers, which acts as a disincentive for their use by farmers, and therefore can affect yields.

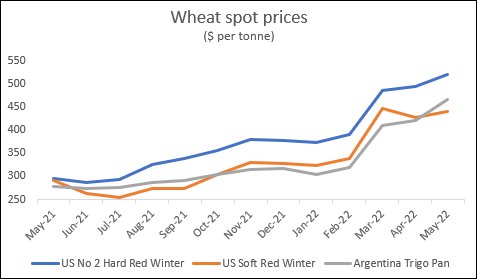

These are surely important but are they sufficient to explain the really sharp increases in global food prices that have been witnessed over the past months? Consider the case of wheat, the crop that is most directly affected by the Ukraine war and the consequent disruptions.

Figure 1 shows how wheat prices have shot up astronomically over the past year. The average of three important wheat prices increased by 165 per cent between May 2021 and May 2022, with the bulk of the increase coming after February 2022. In the case of U.S. Hard Red winter wheat, the price increase was as much as 176 per cent over this same period. This rapid rise echoes the prices increases of 2007-08, the last global food crisis, when it subsequently emerged that financial speculation in the food markets was an important driver of the sharp increase and then decline after June 2008.

Figure 1. Source: FAO Food Outlook June 2022, Appendix Tables 2A and 2B

In the 2007-08 food crisis, one telltale indicator was that global supply and demand (estimated in terms of total production and “utilization”) changed very little, and certainly not enough to explain the dramatic changes in prices that occurred over that period. In fact, despite all the hype in the media and the finger pointing by some politicians, that is also the case today: the Ukraine war has definitely impacted production and trade, but not by all that much, and definitely not by enough to justify the dramatic prices hikes that are being experienced.

Consider the evidence provided in Table 1, which are also from the FAO’s own projections. According to these estimates, the estimated global production of wheat in 2022 is likely to be lower than in 2021 by about 6 million tonnes. But that is a decline of less than 1 per cent, and global production in 2022 is projected to be around 2 per cent higher than the average of 2018-20. Global trade in wheat is also projected to fall slightly in 2022, but it will still remain higher than in 2018-20. Total consumption (or utilization) of wheat is actually projected to be lower than production, to the point that stocks are likely to increase in 2022. And global per capita food use will barely budge.

Table 1. Source: FAO Food Outlook June 2022, Appendix Tables 2A and 2B

This should not really be such a surprise. After all, Russia and Ukraine together accounted for less than 14 per cent of global wheat production in 2021, and it has often been the case that crop production in other regions of the world has gone up to counterbalance declines in output in specific areas. Indeed, even in 2007-08, similar and much-repeated concerns about the impact of specific supply constraints in particular countries turned out to be unwarranted because of increased production in other regions.

If that is the case, and if the broad global totals of supply and demand are not supposed to change that much even with the Ukraine war, what explains the dramatic increases in wheat prices? Two factors are likely to be playing a significant role, and both stem from and now rely on the general public perception that the current food crisis is all about war-related supply shocks. One is profiteering by major grain trading agribusinesses, which have already shown dramatic increases in profitability in January-March 2022 as they have raised their prices without being questioned, as everyone assumes that this is the result of war-driven supply shortages. The other is financial speculation in wheat futures markets, which can drive up prices even in spot markets.

Figure 2. Source: FAO Food Outlook June 2022, Appendix Table 22.

Figure 2 shows how futures prices for wheat have been moving upwards rapidly, particularly in contracts from 11 May onwards. The contracts falling due in July, September and December all showed rapid acceleration in average prices particularly between 11 May and 18 May. This is typical of speculative bubbles, which are often driven by news, but also tend to be affected by herd behaviour that intensifies particular tendencies even if they are not warranted by any real processes.

The increased speculative activity is confirmed by important work done by Kabir Agarwal, Thin Lei Win and Margot Gibbs, who have tracked the activities of financial investors (investment funds in particular) in commodity markets. They find that, for example, “in the Paris milling wheat market, the benchmark for Europe, speculators’ share of buy-side wheat futures contracts has increased from 23 per cent of open interest in May 2018 to 72 per cent in April 2022.” Similarly in May 2022, speculators’ long positions (buying positions) constituted over 50 per cent open interest in Hard Red Winter and Soft Red Winter wheat varieties.

As long as this is not recognized, it will not be addressed by public policy and by regulators who are in a position to control the tendency. The almost exclusive emphasis on the fall-out of the war in Ukraine as the cause of the price spike points to the absence of such recognition. Meanwhile, hundreds of millions of people will face more hunger and even starvation, as the explosion of food prices puts even basic nutrition out of their reach. If we want to deal with the escalating food crisis, we must recognize all the causes.

[C. P. Chandrasekhar was Professor at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Jayati Ghosh is Professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, USA. Courtesy: MacroScan, a website seeking to provide an alternative to conservative and mainstream positions in economics.]