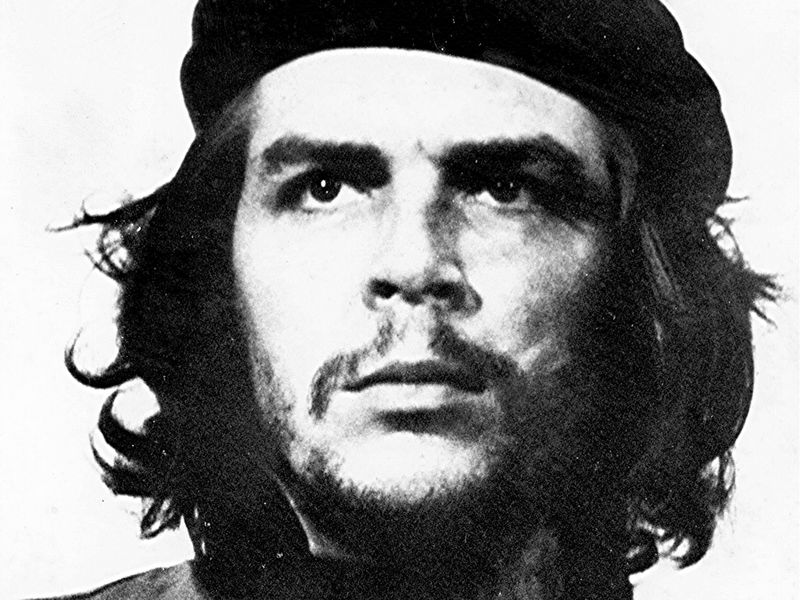

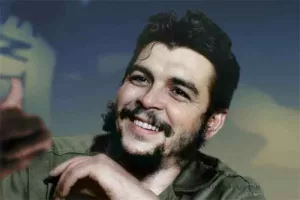

(We are publishing this article in memory of Che Guevara, who was born on June 14.)

In light of a recent upsurge in denunciations of Che and the Cuban Revolution, it is important to separate fact from fiction.

Here are five important points to take into account, all in historical context, drawn from countless reliable sources.

First, there is a burgeoning school of professional Cuba bashers, including some self-proclaimed leftists, who in effect seek the overthrow of the Cuban Revolution.

Apparently expecting perfection, they tend to only see the failures of the Cuban Revolution and its historical leaders. In so doing, they distort the truth beyond recognition and base their arguments on such outright lies as describing Che as “an ardent Stalinist” wedded to “authoritarian ways,” or saying the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) are used for “spying on and controlling people”.

In reality, however, the CDRs were and continue to be key institutions of the evolving and by no means perfect participatory socialist democracy the young revolutionaries set about trying to establish in 1959 in the face of continuous US aggression abetted by diehard supporters of the overthrown Batista dictatorship. This offensive has continued till today, 60 years later, by maintenance of the economic blockade, control over Guantánamo, acts of terrorism, military threat, a sophisticated cultural offensive and financing “dissidents”, CIA agents and NGOs inside Cuba, not to mention the mendacious slanders spewed forth by the mass media of disinformation, including through the social media.

Second, Che understood the centrality of ethics in politics, the centrality of subjective factors in revolution, leading to the rapid transformation of Cuban society into a giant school of reclaiming Cuban culture and ethical values.

Hence, the literacy and “voluntary labour” campaigns, the advances in education and medicine, and the large scale involvement of people in movements for agrarian reform, housing reform, and so on. These movements and campaigns converted idealistic goals largely based on the thoughts of Martí, Mella, Guiteras and other revolutionaries in Cuban history into on-the-ground realities that have continued to evolve, making possible what one could have never imagined even in one’s wildest dreams.

Third, rejecting the use of capitalist methods to fight capitalism, Che and Fidel used the methods of socialist praxis to transform what began as a national liberation struggle into a socialist revolution that would transform institutions and social and human relations through an organised and conscious “praxis” that—despite errors recognised publicly by both of them and their successors—continues till today.

Fourth, Che had repeatedly warned about the dangers of not seeing the deficiencies of “existing socialism” and of mechanically copying Soviet manuals and methods. He had spoken about this often, and this is also explicitly stated in his writings preserved in Cuba and available around the world. He observed that the “intransigent dogmatism of the Stalin era has been succeeded by an inconsistent pragmatism . . . returning to capitalism.” He saw the actions and programmes of the Cuban Revolution as “clashing with what one reads in the (Soviet) textbooks” and contributed insightful socialist critiques of both capitalist and socialist societies and their theories.

Fifth, Che, like Fidel, was profoundly committed to the cause of peace, but unfortunately had to take up arms to move the world closer to that ephemeral goal. To make a world without war possible, Che gave his life, even as Fidel did. We can learn much from their examples.

(James Cockcroft is Internet professor for the State University of New York, a poet, three-time Fulbright Scholar, and a veteran activist.)