Our sense of smell is an inseparable part of our lives. Our environments and bodies are laden with smells. And it is not surprising that humans have sought to control what they can smell. Our sensorial smell is so powerful that we have made smell a political and cultural tool of inclusion and exclusion, purity and pollution.

Smell has been historically one of the bases of defining the social ‘other’. The colonial British painted Indians and other colonised bodies as dirty and sweaty; casteist and Islamophobic individuals often characterise Dalit or Muslim neighbourhoods as ‘stinky’, some Westerners complain of Indian food or other ‘ethnic’ food as ‘unbearable smelly’.

The world is often divided between good smell and bad smell. The world of bad smell is negotiated through the manual labour of underpaid, marginalised labour, including those who work with hides and skins, animal carcasses and sewage. But the world of good smell is likewise a world of labour, and this essay focuses on artisans and labourers who manufacture perfumes.

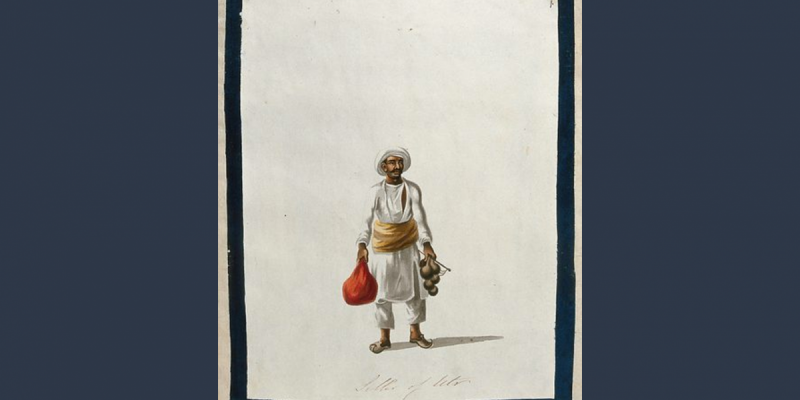

Perfumes evoke a world of emotions, a consumption of scents that remind us of beauty, love or perhaps the distillation of a garden or the natural world. Embedded in each dash of perfume is a history of labour and artisanal skill. Tracing the history of perfumers – Gandhi and ‘itr-saaz in Hindi and Urdu – reveals worlds of labour migration, processes of industrialisation and indebtedness among workers, and the pressures of global trade.

Perfumes, as a luxury item, featured in the courtly politics and the self-fashioning of nobility in pre-colonial South Asia. They also had a bazaar life in ancient and medieval India. The use of sandalwood in Hindu religious events, attars in general, and exotic perfumes, found mention in ancient and early modern Sanskrit, Pali and Persian records.

From the Ain-i Akbari, the administrative records of Akbar’s court compiled by Abul Fazl around 1590, we learn that perfumes made of rosewater and musk were sold by the bottle for Rs 1-3. Conversely, scents that were more precious and difficult to source, such as those made from ambergris, were sold in smaller quantities for far greater prices, fetching several mohars (gold coins), perhaps putting them beyond the reach of anyone but courtly elites. Because of the cost of sourcing materials, most bazaar-based artisan perfumers were likely confined to producing more accessible products, while those who produced more expensive scents were patronised directly by the court.

Systematic trade statistics on the perfume industry before the mid 20th century are limited. As per the Essential Oil Advisory Committee Report of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research in 1946, India exported more than Rs 20 lakh worth and imported about Rs 16 lakh worth of essential oils in 1938-39. Overall, the industry with its raw material had a trade of over Rs 1 crore. The report characterised India as a key producer and consumer of essential oils and attars but lamented the import of cheaper synthetic perfumes from the West, which disrupted the economics and consumption patterns of the India-made essential oils and attars. However, despite ongoing concerns about threats to the industry, some Indian oil and attar-makers have negotiated major shifts in the political economy over the last century. Today, the growth of the fragrance industry in India stands to cross the $1-billion mark by 2026.

Indian attars are distinct from Western perfumes because they are usually distilled using an oil base, rather than the alcohol base that dominates European perfume production. Among the most important oil bases for Indian perfumes was – and remains – sandalwood. The production of sandalwood attars was, by the 19th century, closely associated with the town of Kannauj, in present-day Uttar Pradesh. The labour-intensive process of producing an attar in Kannauj involved first collecting or importing sandalwood, then extracting the oil by boiling split or chipped wood in a copper pan. The sandalwood was then often used as a base for distilling scents from flower petals, which were heated in a dīg, or still, and connected to a bhapka, or receiver, containing the sandalwood base, through a bamboo pipe.

Among the most significant changes to the perfume-making industry in the colonial era was the emergence, in the late-19th century, of larger firms that coordinated and recruited labourers for these varied steps of production. Small-scale artisan perfumers in India faced debilitating competition from imported scents. The new, larger-scale firms were able to control networks of production and distribution, keeping prices low enough to compete with synthetic perfumes manufactured in Europe which, according to a 1908 report, ‘closely resemble[d]’ the attar of the United Provinces.

In fact, vernacular-language texts aimed at the emerging business and capitalist classes in north India specifically encouraged the opening of perfume or soap-making factories as means of building one’s industrial influence. For instance, a 1900 Urdu-language compendium of trades aimed at aspiring industrialists in Kanpur explained the materials one would need to acquire to begin manufacturing perfumes. It suggested that those who hoped to own perfume workshops should begin by manufacturing sandalwood solvents, advising them on the style of dīg to purchase and how to set up a workshop. Labour was largely absent from this narrative, but the text was written with the assumption that capitalists would have to scale up to make their workshop profitable, suggesting a reliance on both artisan labour and agriculturalists.

Perfume-making firms in late 19th- and early 20th-century India relied on the fact that workers migrated seasonally across the subcontinent, purchasing wood and flowers in regions where they grew better and selling them to firms that distilled, refined and distributed the perfumes. This system had a long history, in which members of castes associated with gardening or cultivating flowers migrated to collect flowers and wood, and then sold them to perfumers in towns known for their perfume industries. What changed, around the turn of the 20th century, was that these cultivators and flower collectors were increasingly associated with larger firms. They were sent from major centres of perfume production and distribution such as Kannauj – still referred to as ‘the perfume capital of India’ – to the Central Provinces and princely Hyderabad and Mysore States to collect lemongrass, sandalwood and keora, which grew better in those regions.

The organisation of the perfume industry in Kannauj is suggestive of the relationships between labour and emerging capitalists in the early 20th century. By 1908, the attar industry at Kannauj was dominated by ‘five or six capitalists’. These local industrialists contracted workers to import sandalwood, especially from Mysore State. They also relied on a marginalised and often migratory labouring community of ‘julahas’, a caste group of both Hindus and Muslims usually associated with weaving. Fuel was especially expensive in Kannauj, so julaha labourers migrated to cities such as Bahraich, where fuel was cheaper, to distill sandalwood oil and bring it back to the factories, workshops and distribution centres in Kannauj.

By the 1930s and 1940s, even large-scale Indian perfume-making firms struggled to keep up with foreign competition, and especially the rise of synthetic oils and perfumes. The industry underwent form of ‘deindustrialisation’ between the 1920s and 1940s, moving away from the larger, consolidated model of workshop to smaller-scale artisanal cottage style production. An important element of the mid-20th-century artisanal production of attar in Kannauj and other major centres of perfume in India was debt and indebtedness. Labourers responsible for collecting and distilling oil were often indebted to a town-based attar-saz, who lent them money for their travel but took these costs out of their wages. The attar-saz himself may have been indebted to merchants from major cities like Calcutta and Bombay, who commissioned attar seasonally.

As a result of diminishing profits and growing debts, by the time of Indian independence in 1947, some perfumers in towns such as Kannauj began adding synthetics or aromatic chemicals to their attars. This process was decried by the ‘Essential Oil Advising Committee’ for diluting the distinctiveness of the Indian trade but reflected the economic precarity faced by many producers. The production Indian attar is often contrasted with the production of alcohol-based and synthetic perfumes. However, by the mid-20th century, some Indian artisans engaged with both, adapting to compete in a perfume economy overwhelmed by imports.

Through fieldwork in Kannauj, Amrita Chattopadhyay has demonstrated both continuities and shifts in the present-day labour of perfume production. She notes that the distillation practices of contemporary perfumers retain a high level of similarity to those used in the past, relying on the dīg and bhapka system. Moreover, she highlights the overlapping systems of labour between farm and agricultural workers and perfume manufacturers, with perfumers relying on farm workers to pick “jasmine and other petals and deliver them to the nearby perfume distilleries” each morning. The complex systems of agricultural and artisanal labour that characterised attar production in colonial India thus persist today in Kannauj.

Whether we consider the bazaar-based artisan perfumes of medieval and early modern India, the larger firms of the mid-19th century, or the small scale ‘cottage industry’ perfumers of the mid-20th, it is clear that scent production cannot be divorced from labour. When we dab a bit of attar on our wrists, we engage with overlooked stories of labour migration and marginalisation, technological and material change, and competition and changes in taste wrought by colonialism. At the same time, when we use Indian attars to cloak our bodies in good smells, we engage with an artisan industry that has survived – perhaps against the odds – the pressures not only of the colonial economy, but of contemporary globalisation and neoliberalism.

(Dr. Amanda Lanzillo is a postdoctoral fellow with the Princeton University Society of Fellows, and lecturer in the Princeton Department of History, where she writes and teaches on South Asian history. Dr. Arun Kumar is an Assistant Professor of British Imperial, Colonial & Post-colonial History at Nottingham University. He writes on the modern history of India. Courtesy: The Wire.)