If there is a global fan club for Pope Francis comprising non-Catholics, I want to be its active member. The reason is simple. No other religious leader in contemporary times has been so consistently and passionately vocal on so many pressing challenges before humanity.

He called for urgent global action to save Earth, which he has described as our “common home” in his landmark Laudato si’ encyclical released ahead of the Paris climate summit in 2015. With a bold initiative to advance Christian-Muslim dialogue, he promoted inter-religious concord and understanding. He made strenuous efforts to resolve conflicts and end wars, such as in Syria and Iraq. He also raised a strong voice against the shocking, and growing, levels of wealth disparity that have aggravated the sufferings of the global poor. He appealed for an end to the “spiritual famine” and “globalisation of indifference” that have impaired humankind’s ability to create a better future for itself.

Argentina-born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who was elected the 266th head of the Roman Catholic Church in March 2013, took his papal title in honour of Saint Francis of Assisi, Italy. In the course of my own humble efforts in promoting inter-faith dialogue, I have twice travelled, as a Hindu pilgrim, to Assisi. Why as a Hindu pilgrim? Because the greatest Hindu born in the modern era, Mahatma Gandhi, was deeply influenced by the life and teachings of Saint Francis (1182-1226).

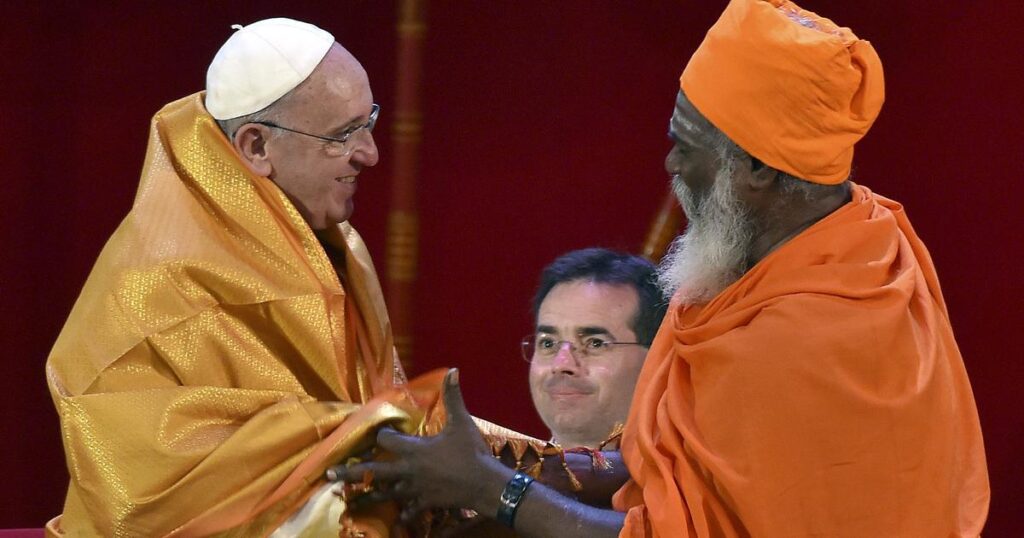

It was in Assisi that I met Pope Francis in 2017, presented to him my book on Mahatma Gandhi and conveyed the wish of millions of Indians that he should visit India. “Yes, I want to,” he said, his eyes displaying a special sparkle as he spoke. “I am eager to come to India.”

Sadly, Narendra Modi’s government has not responded positively to repeated requests from the Catholic Church in India to invite him. It would be a pity if he ends his papacy without ever having come to the land of the Buddha, Mahavira, Shankara, Guru Nanak, Kabir, Basava, Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti, Swami Vivekananda, Gandhi, Aurobindo, Mother Teresa and countless other rishis and saints.

The more I have studied the lives of Mahatma Gandhi, Saint Francis and Pope Francis, the stronger has been my conviction that the three great personalities are united by the silken thread of “godward faith and manward love”. (These are not my words. I have read them in the writings of Swami Ranganathananda, a renowned disciple of Swami Vivekananda.) This essay is an attempt to describe my own discovery of the common spiritual kinship among them.

First, a confession. I am not a scholar of religions. I am just a student of religions. Someone who became a student rather late in life, after believing for many years in Karl Marx’s description of religion being the opium of the masses. It was a time when Marxism was the opium of my life. I was intoxicated by it for many years. Thereafter I began studying religions, first my own, Hinduism.

Hinduism convinced me that all religions are but different paths to God-realisation – what Krishna says in the Bhagawad Gita. This has protected me from the “my religion is superior to others” virus, which sadly infects many people who claim to be religious.

Tryst with Christianity

I was drawn to Christianity not so much by its theology as by its strong emphasis on the service of humanity. Many non-Christians are ardent admirers of Christian priests, activists and organisations for their devoted service to the poor and the marginalised.

This explains, for example, the widespread outrage in Indian society over the custodial “killing” of Stan Swamy, an 84-year-old Jesuit priest working for the welfare of tribals in Jharkhand. He was falsely charged under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, kept in jail without trial for eight months and was denied bail even when his health was deteriorating.

Another aspect also endeared me to Christianity – its willingness to engage in inter-faith dialogue. One day, about 20 years ago, I came across a book at Chetana, a nice little book store near Kala Ghoda in Mumbai that specialises in religious and spiritual literature. It was titled Jnaneshvari: Path to Liberation. Jnaneshvari is a highly revered rendering of the Bhagwad Gita from the original Sanskrit into poetic Marathi by Saint Jnaneshwar, one of the greatest exponents of bhakti marg (path of devotion) in India’s medieval history.

The first thing that struck me was that the book was written by a reputed Christian priest. Far more notable was the quality of scholarship and deep love of the subject that animated the book. Commending the book in his illuminating preface, Raimundo Panikker, a celebrated author of over 50 works on spiritualism, had written:

“The entire book is carried by an inner vision of the divine which shows that the way to God is not by despising anything of the splendour of the creatures, but only in discovering the true order of things, which require bhakti, karma and jnana – or in Christian language love, faith and hope.”

The author’s name was Felix Machado. I was quite surprised that a Christian priest could write such an erudite book on a Hindu saint. I bought the book and read it. My surprise turned into admiration for the author.

I later came to know from a very dear friend of mine, RV Pandit, who is a devout Christian, that Father Felix Machado is his nephew, and that he works at the Vatican in the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue. (Pandit, who ran the famous “Nalanda” bookshop at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, was the editor-publisher of Imprint, an influential monthly magazine of yester-decades.)

I developed a keen desire to meet him, and the opportunity came in 2000 when I went to Italy for the first time as a member of the delegation of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Father Machado came to see me and I introduced him to Vajpayee. He presented his book on Jnaneshwari to the Prime Minister, who browsed through it attentively and said, “Yeh toh ek shreshth granth hai, anokhi rachana hai, upayukt rachana hai. Sabhi dharmon ke baare mein aise vidvattapoorna granth anya dharmeeyonke dwaara likhe jaane chaahiye. [This is a great book, a unique and useful work. There should be scholarly books like this on all religions by persons belonging to other religions].” The Prime Minister also called on Pope John Paul II at the Vatican.

The next day Father Machado took me on a guided tour of the Vatican. This was my first opportunity to experience the spiritual and artistic grandeur of Saint Peter’s Basilica. My Hindu faith teaches me to pray to God from every house of worship that I happen to visit anywhere in the world. As I did so at the Vatican, I experienced the same peace and tranquillity within myself as when I have visited a temple, a mosque, a synagogue or a gurdwara.

Conference on ‘conversion’

However, there was one mental hurdle that kept me from developing a deeper respect for and understanding of Christianity. And that was the question of conversions, as practised by some Christian organisations. I used to think – and I still think – that their method of doing religious conversions was wrong. My views on this subject were strongly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi’s own criticism of religious conversions and, especially, the means employed for it.

One day, in early 2006, I got a call from Father Machado from the Vatican saying he would like to invite me for a conference on the subject of “religious conversion”. The six-day event at a monastery in Lariano near Rome was jointly organised by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, Vatican and the Office on Inter-Religious Relations and Dialogue, World Council of Churches, Geneva.

There were about 40 participants from different parts of the world, and from different religions. I was invited to present a Hindu perspective. In my paper at the conference, I tried to explain the Indian understanding of secularism as “sarva panth samabhava” (equal respect – respect and not just tolerance – for all faiths).

I elaborated on the Vedic maxim “Ekam sat viprah bahudha vadanti – Truth is one and the wise interpret and express it differently”. I gave several examples to illustrate my point. Among them was one about the life and teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.

The example was from Millie Graham Polak’s book Gandhi, The Man. Henry Polak and his wife Millie Graham Polak were quite close to Gandhi during his long stay in South Africa (1893-1914). It was Polak, then a young lawyer and editor of a journal, Critic, who had presented John Ruskin’s book Unto This Last to Gandhi. The book had a life-changing impact on him. Ruskin’s Lead Kindly Light became his favourite prayer.

“Is Mr Gandhi a Christian?” a female visitor once asked Millie. The latter asked for further clarification – whether she meant one converted to Christianity or one who believed in the teachings of Christ. The visitor emphatically told she meant former. She was talking about him with some friends and they were wonderstruck that Gandhi knew Christian scriptures so well, and was so fond of quoting the words of Christ frequently. This made her friends think he must be a Christian.

Millie brooded over. What the visitor said was true. Gandhi frequently quoted the sayings and teachings of Jesus. The lesson of the “Sermon on the Mount” seemed to work constantly in his mind and was a source of guidance and inspiration to him. There was a beautiful picture of Jesus Christ that adorned the wall over his desk. (There was no picture of Rama, Krishna or any other Hindu deity.)

When asked why he did not embrace Christianity, Gandhi said that he had studied the Christian scriptures and was tremendously attracted, but eventually he came to the conclusion that there was nothing really special in them which he had not got on his own. He said, “To be a good Hindu also meant that I would be a good Christian. There was no need for me to join your creed to be a believer in the beauty of the teachings of Jesus or try to follow his example.”

Saint Francis and Gandhi

Many Christian observers – notably, Anglican missionary Reverend CF Andrews – saw Saint Francis of Assisi in Gandhi. Andrews was a close associate of the Mahatma, who called his Christian friend Deenabandhu (friend of the helpless). He also affectionately dubbed CF Andrews Christ’s Faithful Apostle, based on the latter’s initials.

Here is a description by Andrews of an incident he witnessed in South Africa during Gandhi’s satyagraha agitation:

“All through the long day, I watched the behaviour of the crowd and their attitude towards Mahatma Gandhi, their leader. It was there for the first time that I could understand the secret of this amazing influence with his fellow countrymen and the reason for their devotion to him.

I can only describe this briefly by saying that my thoughts went back to the Gospel story for an analogy. He was there, in the heart of that multitude that pressed upon him.

They had come to him without anything to eat, and he was busy providing for their needs. An infinite tenderness and compassion shone from his eyes, while the mothers brought their little children to him so that he might lay his hands upon them and bless them.

The crowd would never leave him even for a moment and his patience was inexhaustible. He had no time for himself to rest or take his own meal while he supplied others with food, for they went on pressing upon him and he would not turn them away.

As I have often in memory looked back upon that scene and afterwards recalled many other pictures also of a similar character I have been able from time to time to find the parallels I needed in history. Sometimes the scenes I have witnessed have reminded me of stories about the Buddha.

But most often my thoughts have turned to the legends concerning Saint Francis of Assisi. Mahatma Gandhi is, most nearly of anyone I know, the Saint Francis of this modern age, the little brother of the poor.”

Gandhi never renounced his Hinduism but he often declared himself a follower of Jesus Christ. He studied the gospels and lived by them. I concluded my paper at the conference in Lariano with these words:

“God has created diversity – and not uniformity – as the essential principle of the architecture of this universe. This is as true about the physical or material side of Nature, as about the social and the spiritual side of man’s life.

Therefore, what humankind offers to God almighty is a bouquet and not a bunch of flowers of the same colour. God accepts prayers from every pure heart, irrespective of creed…What is needed is an honest and sustained dialogue between the adherents of diverse faiths living on this beautiful planet of ours, so that we can rid it of the curse of hatred and violence in the sacred name of religion.

True religious spirit unites humanity and does not divide it. It promotes universal peace, brotherhood, goodwill and mutual trust and understanding. Therefore, may all of us get “converted” to that truth, uniting and ennobling the religious spirit.”

Pioneers of green movement

Andrews’ description of the similarity between Saint Francis and Gandhi whetted my curiosity. Saint Francis preached the teaching of the Catholic Church that holds that the world was created good and beautiful by God.

He believed it to be the duty of all creatures to praise God and the obligation of all men to protect nature. The underlying thinking behind this belief was that man, as the highest creation of God, is the steward of God’s creation.

This is precisely what Gandhi meant by “Trusteeship” – that man is the trustee of all the non-human creatures in the world. This belief is rooted in the first verse of the Isha Upanishad that states:

“Everything animate or inanimate that is within the universe is controlled and owned by the lord. One should therefore accept only those things necessary for oneself, which are set aside as one’s quota, and must not accept or covet other things, knowing well to whom they belong.”

Gandhi extolled this verse for conveying a message of universal brotherhood – not only the brotherhood of all human beings, but of all living things. Trusteeship can be called the kernel of Gandhian socialism: “When an individual has more than his proportionate portion, he becomes a trustee of that portion for other creations of God”.

We can see here how beautifully ancient Indian philosophy has linked the concepts of non-stealing, nonviolence, trusteeship and socialism (“each for all and all for each”).

Indeed, Gandhi extended the concept of trusteeship beyond economics to the realm of the environment.

Gandhi wrote:

“It is an arrogant assumption to say that human beings are lords and masters of the lower creatures. On the contrary, being endowed with greater things in life, they are the trustees of the lower animal kingdom.”

He wanted “to realise identity with even the crawling things upon the earth, because we claim descent from the same God, and that being so, all life in whatever form it appears must essentially be so”. In a highly original reinterpretation of colonialism, the Mahatma affirmed that lording over nature and lording over other “inferior” people are both manifestations of colonialism.

Saint Francis lived in an altogether different era, nearly eight hundred years ago. Nevertheless, environmentalists worldwide regard him as the Green Saint, or the Patron Saint of Ecology. Many of the stories that surround his life say that he had a great love for animals and the environment.

Here is a story:

“One day, while Francis was travelling with some companions, they happened upon a place in the road where birds filled the trees on either side. Francis told his companions to “wait for me while I go to preach to my sisters, the birds”. The birds surrounded him, attracted by the power of his voice, and not one of them flew away. In Christian iconography, he is often portrayed with birds, typically with one in his hand.”

Saint Francis of Assisi

One of Gandhi’s favourite Christian saints was Saint Francis of Assisi.

Gandhi wrote:

“Saint Francis was a great yogi in Europe. He used to wander in the forests among reptiles, but they never harmed him. On the contrary, they were friends with him.

Thousands of jogis and fakirs live in the forests of India. They move fearlessly among tigers, wolves and snakes, and one never hears of their coming to any harm on that account. We are told and we believe it to be true that these jogis and fakirs keep no weapons with which to withstand these beasts.

I personally feel that when we rid ourselves of all enmity towards any living creatures, the latter also cease to regard us with hate. Compassion or love is man’s greatest excellence. Without this, he cannot cultivate the love of god. We come to realise in all the religions, more or less clearly, that compassion is the root of the higher life.”

On another occasion, Gandhi wrote:

“Our shastras teach that a man who really practices ahimsa in its fullness has the world at his feet, he so affects his surroundings that even the snakes and other venomous reptiles do him no harm. This is said to have been the experience of Saint Francis of Assisi.”

In one of his letters to his own ashramite, Mahatma Gandhi wrote:

“I am sending you a beautiful letter received from a lady living in an ashram like ours in Italy. All the workers in that ashram are women. The letter will give you some idea of the devotion and patience with which they work. Explain its contents to all the inmates, particularly to the women. Tell them at the same time about Saint Francis. Mahadev once wrote a sketch of his life for Navajivan.” [Mahadev Desai was Gandhi’s trusted secretary. Navajivan was a Gujarati newspaper founded by Gandhi.]”

The opportunity to know more about Saint Francis – also about Pope Francis – came to me fortuitously. In 2013, the Vatican got a new pope, one from outside Europe for the first time.

In the same year, both Archbishop Machado and I were invited to participate in a global inter-religious conference in Rome. It was organised by the Community of Sant’Egidio, a voluntary spiritual organisation inspired by Saint Francis and dedicated to “serving the poor, inter-faith harmony and conflict-resolution”, three activities that were also close to Gandhi’s heart.

I presented a paper on the misuse of religion for terrorism and other types of violence. But what made this third visit of mine to Italy truly unforgettable was the opportunity to go on three “pilgrimages”.

The first pilgrimage was of course to the Vatican itself. The second was to the house in Rome where Mahatma Gandhi lived during his historic visit to Italy in December 1931. The third was to Assisi, the janmabhoomi (land of birth) and tapobhoomi (land of spiritual service) of Saint Francis.

Gandhi in Rome and Vatican

To me, every place associated with Mahatma Gandhi’s life is a place of pilgrimage. Among his many photographs that I cherish, the one that always leaves me transfixed shows him in a meditative pose – sitting cross-legged in deep silence with eyes closed and turned inward.

Beneath the photo is written: “Where he sat became a temple.” I have experienced this sacredness at Kirti Mandir in Porbandar where he was born, Mani Bhavan in Mumbai where he stayed for many years, Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Phoenix Settlement near Durban that was his first ashram in South Africa, Gandhi Smriti in Delhi where he spent the last day of his life and, of course, at Raj Ghat.

I had the same experience when I visited Gandhi’s “home” in Rome, at 103 Via Massimi. It happened to be Gandhi Jayanti. It was not easy for me to get to that place. Father Machado, who was familiar with Rome, had given me the right bus number to reach there, but I got down at the wrong stop.

I could find no English-speaking person to help me with the right directions. It took me two hours of walk to finally reach my destination. I realised that, as in ancient times, one cannot hope to go to a place of pilgrimage without a difficult trek on foot!

A marble memorial plaque at the entrance of the house, located in a peaceful residential neighbourhood, had an inscription in Italian. It was installed in 1981 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Mahatma’s stay there.

The gate to the house was locked. The street was empty. The golden rays of the evening sun cast a mysterious light on the tall trees surrounding the beautiful house. An old man passing by saw me clicking pictures. He came to me and asked, “You from India?” My answer seemed to make him very happy. He exclaimed in Italian, with a few broken words in English: “Ghandi, great man, great man. No man in the world like him….My heart, Ghandi in my heart…”

The Mahatma had visited Italy on his way back from the failed Second Roundtable Conference in London. He knew the London roundtable, organised by the British government to discuss constitutional reforms in India, was doomed to fail. But his real purpose of undertaking an extended journey to Europe was to broadcast his message of truth, nonviolence and universal brotherhood at a time when dark clouds were again hovering over the continent’s sky. While in Rome, and against the advice of many, he went to meet Benito Mussolini because of his conviction that the pursuit of peace through principled dialogue could not exclude anybody, not even dictators and tyrants.

The highlight of Gandhi’s visit to Italy was his visit to the Vatican. Shockingly, the Pope refused to meet him, an indication of how far the church had moved away from the essential message of Christianity. The outward grandeur of the Vatican did not impress Gandhi much. But he was spellbound by a particular statue of Christ on the cross above the altar of the Sistine Chapel. The profound effect it had on him was later described by Mirabehn, who accompanied him on his European journey:

“He remained perfectly silent, as if still in contemplation. He then said, ‘So deep an impression did that crucifix make on me that it stands out all alone in my mind, and I remember nothing else of my visit to the Vatican.’”

After reading this, I wondered: When the Mahatma stood in front of the statue of Christ, was he having a premonition of his own death 17 years later?

The Vatican press at the time scorned Gandhi’s visit. However, in 1986, John Paul II visited Raj Ghat in Delhi, and said, “Today, as a pilgrim of peace, I have come here to pay homage to Mahatma Gandhi, a hero of humanity. The figure of Gandhi and the meaning of his life’s work have penetrated the consciousness of mankind.”

There is another proof of how the Vatican changed its views on Gandhi. Visitors to the office of the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue (where Father Machado worked for many years) are greeted by a large painting at the entrance.

The painting shows a scene, imagined by the artist, of the Pope, welcoming a group of religious leaders from different parts of the globe, and representing different faiths, to the Vatican. Bernini’s magnificent 17th-century colonnade that encompasses Saint Peter’s Square can be seen in the background. But what is most eye-catching in the painting is that the very first person among the spiritual dignitaries being welcomed by the Pope with extended hands is a dark-skinned saintly man clad in white dhoti with a walking stick in his hands – Mahatma Gandhi!

There cannot be a more eloquent contrast between one Pope refusing to meet the Mahatma when he actually visited the Vatican, and another Pope welcoming him to the Vatican through the timeless medium of art.

There is a beautiful account of Gandhi’s visit to Italy by Maria Montessori, the legendary Italian educationist whom he greatly admired. She described a prayer meeting held at the house at 103 Via Massimi:

“His [Gandhi’s] spirit is like great energy that has the power of uniting men because it effects some inner sensitivity and draws them together. This mysterious and marvellous energy is called love. I felt this very deeply when Gandhi paid a visit to Europe and stayed a few days in Rome on his homeward voyage.

During his stay in his honour, and while he sat on the floor and spun, children sat around him, serene and silent. And all the adults who attended this unforgettable reception were silent and still. It was enough to be together, there was no need of speeches. We must think about this spiritual attraction, it is the force that can save humanity, for we must learn to feel this attraction to each other, instead of being merely bound by material interests.”

Pope echoes Gandhi

From Rome, I sent an article to The Indian Express, titled: ‘Why Gandhi resonates in Rome”.

I wrote:

“Rome, the Eternal City, is still as inviting as ever. But there is a certain new thinking in the air in Italy’s capital, born of three factors – prolonged economic recession, political instability and the arrival of a progressive new Pope in the Vatican. Like millions of non-Christians around the world, the new Pope has fascinated me.

He was variously called the ‘poor people’s Pope’, ‘Pope from the slums’, ‘radical Pope’, ‘reformist Pope’, ‘Pope of paradoxes’ and also ‘the unpredictable Pope’. One thing was immediately clear – there was a close similarity between Gandhi’s rejection of economics without ethics and the Pope’s flaying of the current global economic system that has put “an idol called money”, and not people, at its heart.

Speaking extempore to loud applause from a large crowd of unemployed youth in Sardinia, the Pope said, ‘Let us all fight the money idol, against an unfair system without ethics in which money rules everything. To protect this idolatrous system we abandon the weakest, the elderly, those who have nowhere to sleep… Even the young are abandoned and left without dignity.’”

Here I turn to a page in my book on Gandhi:

“The introduction of justice and moral values as a factor to be considered in regulating international commerce was, according to Gandhi, the touchstone of ‘the extension of law of nonviolence in the domain of economics’.

He declares: ‘Economics that hurts the moral well-being of an individual or a nation are immoral and therefore sinful.’ Much of what Gandhi said or wrote about economics negates the foundational principles of modern economic theory and practice. ‘True economics,’ he affirms, ‘is the economics of justice.’

He calls it the first principle of every religion. His castigation of colonial Britain was on account of the fact that the economics it practiced was a violation of the religion of Jesus that it preached. He wrote: ‘I know no previous instance in history of a nation’s establishing a systematic disobedience to the first principle of its professed religion.’

Gandhi reminds us that all the scriptures of the world, ‘which we [verbally] esteem as divine” denounce “the love of money as the source of all evil, and as an idolatry abhorred of the deity”. They also declare ‘mammon service to be the accurate and irreconcilable opposite of god’s service’.”

The new Pope was saying the same in his own ways. Since then, “A poor church for the poor” has become Pope Francis’s clarion call.

This slogan emphasises – and there is a message in this for religious establishments of all denominations – that the church would be judged not by its riches and its outward grandeur but by its determined reaching out to the victims of poverty, exploitation, misfortune and consequent despair.

This, surely, is a new moral voice in the world, urging radical transformation as much in the internal working of the Vatican as in the unjust, unethical and opaque economic and political systems governing the human race. And he is influencing a new thinking in Europe and elsewhere in the world. This new thinking is further amplified by his historic Laudato si’ document, which reminds us that “the cry of the Earth and of the Poor is becoming more and more heart-breaking”.

‘Poor people’s Pope’

This brings me to my third pilgrimage – to Assisi. After the conclusion of the inter-religious conference in Rome, I went to Venice for a day. Venice was charming, but it left an inner emptiness in me.

The next day I took a train to Assisi. It is a small town on top of a mountain. It has the look and feel of a monastery. Like all Italian towns with old buildings, Assisi is also beautiful. But its beauty has rare simplicity, almost as ascetic as the personality of the saint who has made it globally famous.

Pope Francis had come to Assisi the previous day. And the town was still full of banners, balloons and other decorations welcoming him. The lady at the local tourism office told me with gushing enthusiasm: “Forty thousand people came here yesterday. Never before so many.”

The air of Assisi still reverberated with the wise words spoken by the new Pope, words that echoed the timeless wisdom of Saint Francis himself. In his extempore speeches and impromptu interactions, Pope Francis amplified two inter-related messages that are at the core of Franciscan philosophy: care for the poor and peace in the world.

“From this City of Peace,” the Pope said, “I repeat with the force and meekness of love: let us respect creation, let us not be instruments of destruction!” Christians and others cannot be unconcerned about those in the world who suffer in situations of poverty or other hardships, he said.

He spent many hours with disabled children, jobless youth and poor immigrants, and sat with them for lunch, eating the same food they are daily served by a local charity. “Many of you have been stripped by this savage world that does not give employment, that does not help, that does not care if there are children in the world who are dying of hunger,” he said.

He expressed grief over the deaths of over a hundred African migrants, who had drowned when their boat sank near the Italian shore. “Today is a day of tears…It is a disgrace. The world does not care about the many people fleeing slavery, hunger, fleeing in search of freedom.”

Then, in what has now become the main theme of his papal pronouncements, he denounced unbridled materialism that has enslaved the modern world. Referring to Saint Francis disrobing himself before God in an act of renunciation and also an act of solidarity with the poor, he urged, “All of us must undress ourselves from this worldliness, which is contrary to the spirit of Jesus.”

He warned that worship of money and worldliness are “the cancer of society” that “lead us to vanity, arrogance, pride”.

Harbinger of radical change

Why does Pope Francis’s call for a radical change in the church, and also in the world beyond, ring authentic? It is because his own life in some ways embodies the change. There is a fabulous book Pope Francis: Untying the Knots by Paul Vallely, which tells, in a critical and non-hagiographic style, the story of how this self-confessed sinner – “I committed hundreds of errors and sins” for which “today I ask forgiveness” – underwent an inner transformation that enriched him spiritually, changed his worldview, made him humble and, at the same time, deepened his fixity of purpose.

Saying no to occupy the Apostolic Palace – “There is room for 300 people here. I do not need all this space” – he chose to live in a spartan guest house in the Vatican. In another unprecedented tradition-breaking move, he went, within days of becoming Pope, to a prison in Rome and washed the feet of twelve prisoners, including those of women, Muslims and atheists.

Since 2013, I have been participating in the inter-religious dialogue meetings organised by the Community of Sant’Egidio each year in different cities in Europe. One scholarly person from Argentina I have often met at these conferences is Rabbi Abraham Skorka, who has known Pope Francis for over two decades from his days as a priest in Buenos Aires and co-authored with him the widely acclaimed book On Heaven and Earth.

Skorka once told me, “He is totally aware that he must in some sense be a revolutionary Pope, not only for the Catholic Church but for the whole of humanity.”

Having avidly followed all the sayings and doings of Pope Francis as his ardent fan, I am convinced that he is a conscience keeper of humanity in our times.

Should the Modi government not invite this holy man to visit India?

(Sudheendra Kulkarni served as an aide to former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and is the founder of the Forum for a New South Asia. Courtesy: Scroll.in.)