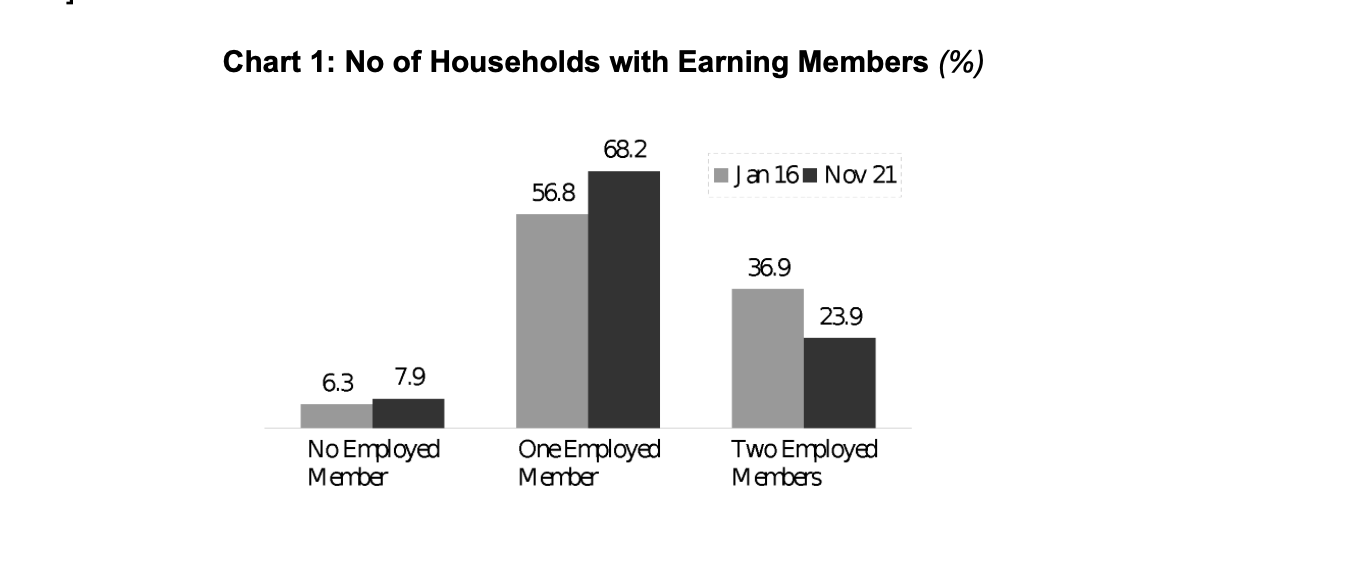

The share of households with two working members has sharply declined from nearly 37% in January 2016 to about 24% in November 2021, according to analysis of latest data collected in the periodic sample surveys conducted by Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Alongside this, the number of households with only one earning member has significantly increased from about 57% to over 68% in the same period [see Chart 1].

Meanwhile, households with no member working have increased from just over 6% to nearly 8% in these five years. These three trends put together reveal a dire – indeed, a desperate – economic crisis that’s haunting common working people of India.

The intensity of this economic crisis can be gauged from the fact that CMIE surveys show that the median income in India was a mere Rs.15,000 in June 2021. With this low level of earning, and with increasing debt, falling savings, households are in a downward tailspin.

The Narendra Modi government, busy in electioneering and aspiring to building a Hindu Rashtra, has no solutions to offer. Indeed, the Prime Minister who once used to emphatically promise jobs everywhere he went, is hardly ever heard mentioning it now.

Explaining Falling Work Participation Rates

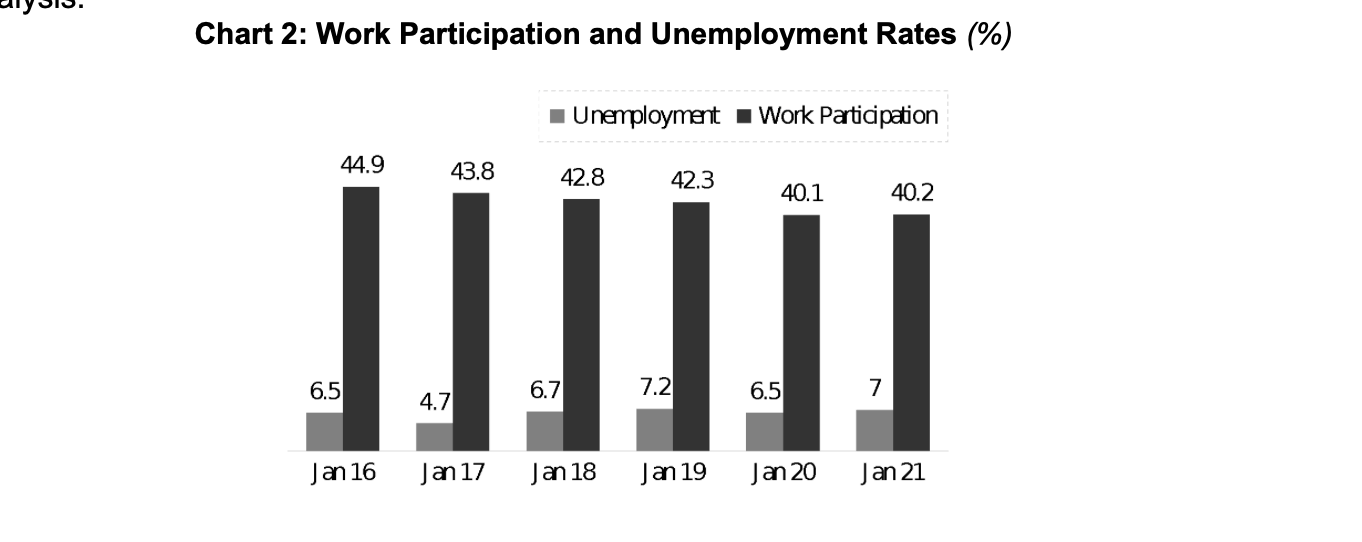

The fact that the number of employed per household is falling is perhaps the reason why India has been exhibiting a paradox of falling work participation rates (WPR), that is, the share of people working and those without jobs but willing to work. In November 2021, India’s WPR was 40.2% compared with 44.9% in January 2016. Currently, India’s WPR is among the lowest in the world. The average WPR for the whole world is about 58.7%, according to the World Bank.

On the other side, the unemployment rate is not reflecting this harsh reality adequately because it tracks only those who are willing to work. Despite that, India’s unemployment rate has been hovering around the 7% mark for three years, which is higher than the preceding average of 5-6%

Clearly, a large segment of the working age population is too discouraged and frustrated with non-availability of jobs and has dropped out of the workforce altogether. This is reflected in the drastic fall in two working member households, according to the CMIE analysis.

Chart 2: Work Participation and Unemployment Rates (%)

Agriculture Absorbing the Most People

Most of the growing population of working age population in rural areas is willy-nilly getting absorbed in agriculture to the point of heavy overloading. Since agricultural incomes are not rising concomitantly, this means more people are sharing the same amount of income from farming and related activities.

The lack of jobs in the largely urban industrial and services sector has discouraged migration as an option for many. That is why a big share of migrants that trekked back home when the first lockdown was announced in March 2020, have not returned to their jobs in cities.

These people are either sharing agricultural jobs or working for a few days in the rural job guarantee programme (MGNREGA), as shown by the exploding numbers in this popular scheme. In 2017-18, about 7.6 crore persons found some work in MNGREGA, which increased to 11.9 crore in 2020-21 and has reached 9.34 crore already by December-end in 2021-22, with another three months to go before the financial year ends.

But, low wages, delays in payment and intermittent nature of work has marred even this programme. The average number of days worked was 52 in 2020-21, which is half the stipulated 100-days minimum that the law requires. The average wage was just Rs.200.7 in 2020-21, which has increased to Rs.209.4 in the current year.

It is a measure of the deep and desperate economic crisis that families are continuing to work in these onerous and barbaric conditions, even as the COVID pandemic continues to devastate the country.

No-Job Families on the Rise

As the first graph showed, the absolute rock bottom level – of families with nobody employed – has increased from 6.3% to nearly 8%. In fact, in 2020, the year of the lockdowns, this share had risen to 11.5%, according to the CMIE analysis. In April 2020, the first full month of the severe lockdown, the proportion was an unimaginable 33%.

Obviously, these are the families that are the most vulnerable and in great need of active and immediate support from the government. While the distribution of free extra rations (that has now been extended till March 2022) would have helped in their surviving the pandemic-related economic downturn, but families don’t just need foodgrains. Various other spending – children’s education, healthcare, clothing, fuel, etc – is needed. But that is out of reach in the face of the jobs crisis.

Will there be political fallout?

In recent years, the complete failure of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in handling the economic crisis, especially the jobs crisis, has emerged as the single biggest rallying point against it. In the recent Assembly elections, the issue reported to be among the foremost in people’s minds was jobs. This has led to a clear erosion of support for BJP, despite all its attempts to create social strife through religious polarisation.

And, as time passes, this discontent is gathering steam. It was reflected in the year-long farmers’ movement, in the protests and struggles of workers and employees that have continued unabated in the past few years. Such is the hardship that people are struggling to just get their earned wages, or preserve minor benefits. Price rise is unbridled and is robbing whatever meagre earnings that exist. So, it is likely that this disillusionment from Modi (and his party) – who had promised two crore jobs every year, once upon a time – will find expression in the ensuing Assembly elections too.

(Subodh Varma is an independent journalist. Courtesy: Newsclick.)