❈ ❈ ❈

From Love Songs to Kurta Ads, Urdu Is Popular with Indians. Why do Hindutva Backers Hate it So Much?

Shoaib Daniyal

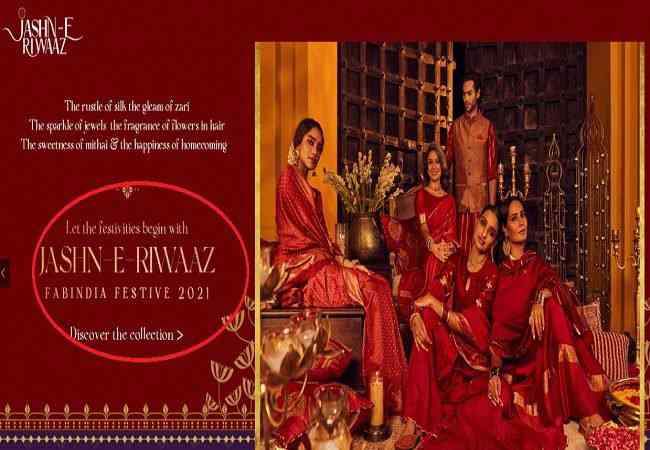

Even by the trigger-happy standards of Hindutva outrage, what happened on Tuesday seemed ridiculous: some Indians, including senior Bharatiya Janata Party leaders, were angry that clothing brand FabIndia had named a Diwali collection using Urdu. They claimed that the Urdu language simply could not be associated with a Hindu festival.

A jumpy FabIndia soon took down the advertisment for the collection and released a statement that assured anyone outraged that the Urdu phrase “Jashn-e-Rivāj” (celebration of tradition) would not be associated with its Diwali collection. Instead, it would have a Hindi name: Jhilmil sī Diwāīi (a sparkling Diwali).

By any standard, the controversy was both ridiculous (how could festivals be associated with language?) and frightening (the mob had enough power to force corporations to bend to their will). But perhaps, the biggest irony was that both phrases, Jashn-e-Rivāj and Jhilmil sī Diwāīi would be perfectly intelligible to Indian Hindi speakers.

The Persian loanwords “jashn” and “rivāj” would, in fact, be seen as common Hindi words with the only explicit “Urdu” element being the genitive marker “-e-” rather than the postposition “kā” (which is shared by both Hindi and Urdu). Nevertheless, even the “-e-” is so common in Indian popular culture such as Bollywood that Hindi speakers would come across it all the time, even if they would rarely use it in their personal speech.

Hindi and Urdu

Due to these incredible similarities – Hindi and Urdu share almost all of their grammar and most of their day-to-day vocabulary – most linguists would often classify Hindi and Urdu as literary registers of the same language (the Khari Boli of medieval Delhi). Registers are language styles used as per occasion or identity. Every language has them, even English.

Think of academic English and the English used for hip hop lyrics. They differ significantly in lexicon but with largely the same grammar. Most importantly, an Anglophone academic and a rapper can, if they chose to, be mutually intelligible and have a conversation. It’s almost the same as Hindi and Urdu speakers, except the choice of who speaks which register is based on religion – a somewhat more ossified identity than professor or rapper.

As academic Christopher King puts it in his book One Language Two Scripts, Hindi and Urdu are “considered two different languages on political and cultural – not linguistic – grounds” such that only “vocabulary and script constitute the principal difference between the two”.

Urdu makes a virtue of borrowing words from mostly Persian, the elite lingua franca of medieval India (even the Arabic and Turkish words in Urdu are via Persian). Hindi, on the other hand, makes sure those very same borrowings are from Sanskrit, a language that enjoys immense prestige in India for its position as the liturgical language of Hinduism.

Notably, the vast majority of the lexicon of both Hindu and Urdu, their core vocabulary, is commonly inherited from its Prakrit ancestor. Thus, often whether a person is speaking “Hindi” or “Urdu” depends on the identity of the speaker or, in the case of written language, the script.

The split

Both modern Hindi and Urdu literary cultures are fairly new, contrary to the claims of their partisans. Persian, in fact, continued as the administrative language and elite lingua franca well after Mughal power had declined and the British star had risen. As academic Francesca Orsini explains, it was only in the 19th century that “Urdu took over the mantle from Persian”. At this time, Urdu was not seen a Muslim language, as it is today but it did have an explicit class element: like Persian, it was as the “language of the service elite and of refined, urban literary exchange”.

In Uttar Pradesh, for example, this meant Urdu was used almost exclusively by Ashraf or upper-caste Muslims along with some Hindu castes traditionally part of the Mughal bureaucracy, such as Kayasths and, to a lesser extent, Khatris and Kashmiri Pandits (most famously, the Nehrus).

Even though Urdu is much attenuated in India today, with only a small section of very poor, mostly madrassa-taught Muslims using it as their medium of instruction, an echo of this class element still survives and Persian-stuffed Khari Boli will often code luxury – as, in fact, in the Fabindia advertisement.

In much the same way, it also survives in cultural forms such as songs and poetry. Even in the absence of Urdu education, Hindi film songs songs will often use, to quote Salman Rushdie, the “thunderclap sound of Urdu” to code high emotion such as romance or patriotism. As historian Mukul Kesavan has argued in his must-read essay on the roots of Bollywood, Urdu is the “language of war and martyrdom in Hindi films. It is the language men die in.”

Resurrecting a 19th-century politics

But if so many Indians love to sing of war and buy kurtas in Urdu, why then do Hindutva adherents dislike it so much?

Part of the answer goes back to the politics of Uttar Pradesh at the end of the 19th century as a new, mostly Hindu elite arose that had no previous connections with the older Mughal elite – and hence Persian and Urdu. In 1882, a campaign was mounted to get the British government to accept Hindi written in Nagri characters as an official language in the North-Western Provinces (which now mostly corresponds with modern Uttar Pradesh), alongside English and Urdu.

Part of the struggle was economic. Urdu domination meant this new, largely Hindu elite were shut out of government jobs.

Part of it was linguistic. Congressman Madan Mohan Malviya, a prime backer of Hindi at the time, complained that the Urdu used in courts was so stuffed with Persian that official records were only “partially intelligible”. (However, as Christopher King pointed out, ironically since much of this new literary language was piloted by Sanskrit-knowing Brahmins, it eventually produced a Sanskritised Hindi, itself far from everyday speech).

However, like almost all other questions of language, this also became a question of identity, given that this new, Hindi elite were, as it so happened, Hindu. “During the [1882] campaign, however, Hindi in Nagari script was successfully turned into a question of Hindu cultural self-assertion, and the united Muslim-Kayastha community of Urdu was shaken,” explained Orsini.

As King argued, “more and more Hindus had begun to accept the twin equations of Hindi=Hindu and Urdu=Muslim”. So successful was this campaign that even Hindus in the Punjab saw significant traction towards identifying with Hindi. At the time, Congressman Lala Lajpat Rai himself promoted Hindi as the language of Punjabi Hindus in spite of, ironically, not knowing it himself.

Legal win

Eventually, of course, the Hindi supporters won a fantastistic victory. While in North India in 1900, Urdu was, in the words of researcher Alok Rai, “overwhelmingly the language of public discourse”, within just half a century, the new Indian Constitution recognised only Hindi as the official language of the Union government, with English given interim status.

Urdu made it to the Constitution as part of a largely perfunctory list of official languages only because Prime Minister Nehru insisted on it.

However, so complete was the communal association of Hindi and Urdu by that time, Rai recounts that “a Hindi friend” asked Nehru whose language Urdu was. “Yeh merī aur mere bāp-dādā’oñ kī bhāshā hai,” Nehru replied. This is my language, the language of my ancestors. Thereupon the “Hindi friend” retorted: Brāhman hote hue Urdu ko apnī bhāshā kehte ho, sharam nahīñ ātī? Aren’t you ashamed, being a Brahmin, to claim Urdu as your language?

Uttar Pradesh, heartland of the Hindi-Urdu fight, went even further, banning Urdu-medium schooling altogether. As Urdu writer and critic Shamsur Rahman Faruqi put it, there was an effort to “wipe out Urdu” in Uttar Pradesh after independence.

Pyrrhic victory

Orsini, however, argues that this victory for Hindi was actually somewhat pyrrhic. For one, it could never actually replace English at the top of the linguistic food chain. English still remains, by far, the language with the most linguistic prestige with immense amounts of economic and social capital.

While Urdu education was severely restricted along with its script as well as its high, ultra Persianised register, demotic Urdu along with a substantial part of its Persian loans still lives on in India. Its 19th-century status as a register of elite society means North Indians still look to Urdu in their cultural consumption.

In contrast, Sanskritised Hindi – which Alok Rai pointedly calls “Hindi” in scare quotes to differentiate it from its spoken forms – has a fairly restricted life outside government and is practically absent from Bollywood, by some distance the largest producer of Hindi-Urdu content in the world.

Of course, Hindutva is ascendantly militant right now and is unafraid to use intimidation to try and resurrect colonial-era Hindi-Urdu debates. However, even as these political controversies break, one must keep in mind that changing language habits – especially the natural spoken tongue – of millions is a tough feat to pull off.

In fact, ironically, the Bharatiya Janata Party uses what could be called “Urdu” too in slogans such as “Modi hai to mumkin hai” (mumkin is from Arabic via Persian) or “āzādī kā amrit mahotsav” (āzādī is a Persian loan). Even words as basic as “Hindu” and “Hindi” are loans from Persian, being taken up by Indian languages in the medieval period. Hence, in the reductive lens of (Sanskritised) Hindi versus (Persianised) Urdu, they fit into the latter silo.

This, of course, does not mean language change cannot occur. In fact, like medieval Khari Boli absorbed Persian words as part of its everyday lexicon, much the same is happening with English today, which given its linguistic prestige and power exerts a significant influence even on non-Anglophones. Open any Hindi newspaper, for example, and it is suffused with English loan words. Informal, spoken speech will probably have even more.

(Courtesy: Scroll.in.)

❈ ❈ ❈

Who Says Urdu is a Muslim Language?

Aviral Virk

‘Badtameez’, ‘Vaqt’, ‘Intezaar’, ‘Zindagi’, ‘Koshish’, ‘Kitaab’, even ‘Hindi’ are just some of the Urdu words we use while remaining totally oblivious of the fact that the language we use is in fact an amalgamation of Hindi and Urdu. 200 years ago, this hybrid language was called Hindustani.

It’s sad, but the stereotypes rule. In our popular and often misinterpreted culture, Urdu and Hindi have become the linguistic equivalents of the skull cap and the tika. But language wasn’t always appropriated by religion.

In the late 1800s, when illiteracy was an estimated 97 percent, administrative, judicial and all other official work in the country was conducted in Urdu. Perhaps thanks to this abominable literacy rate, Urdu was at the time considered the propriety of the educated elite, by default seen as British loyalists. The relatively new language was as progressive and ‘mainstream’ as it could get in a country where only 3 percent of the population knew how to read and write. The Urdu Mahabharat published in 1926 sold 6,000 copies despite being priced an exorbitant Rs 8.

So When Did Urdu and Hindi Take on a Religious Colour?

It began with the division of words. The etymology (origin of words) of Hindustani was identified by British linguist John Gilchrist. This proved to be an ambitious exercise since Urdu and Hindi are closely linked; nearly identical in grammar and manner of speech.

John Gilchrist set up the language training institute at the Fort William College in Calcutta for East India Company recruits. The idea was to help the British administer a complex colony and expand their empire.

Deconstructing Hindustani

Among other things, Gilchrist set out to classify and define Hindustani into two broad categories – words inspired largely by Persian and Arabic were identified as Urdu and those inspired by Sanskrit and Prakrit now known as Hindi.

Perhaps inadvertently, Gilchrist’s efforts gave a quasi-religious identity to both Hindi and Urdu.

The Revolt of 1857

The grammar stood divided, but the language of the resistance during the Revolt of 1857 was still Hindustani.

The Revolt of 1857 taught the British that religion was an evocative issue for Indians after which a concerted ‘Divide & Rule’ policy was followed. Language was a consequent victim.

After the Revolt was quelled, the British started viewing the otherwise “loyal” educated Muslims who they employed in government services as having betrayed them. To balance the scales, the colonial rulers started favouring Hindi writers and the Devanagri script. They even founded universities in Banaras and Allahabad.

The Hindi Uprising

This encouragement from the British government prompted those lobbying for representation of the Devanagri script in government functioning to become more active.

In two separate memorandums submitted in 1873 and 1882, campaigners for Hindi argued that the Urdu script had a tendency to be vague, illegible and encouraged clerical mischief. It accused Urdu of perpetrating an artificial Persian culture and claimed that Hindi users were overwhelmingly more in number than the elites who were favoured by the ruling establishment.

Regarded as the father of modern Hindi literature, Bharatendu Harishchandra referred to Urdu as the “language of the dancing girls and prostitutes”.

Meanwhile, in 1882, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan prevailed upon the British council to ensure that Urdu remained the medium of instruction in schools.

The MacDonnell Moment of 1990

The lack of nuance in previous arguments is what made Congress leader Madan Mohan Malviya adopt a more strategic approach with a memorandum on the introduction of the Devanagri script in Indian administration.

Three years later, lieutenant governor of the North-Western Provinces Sir MacDonnell gave an official endorsement to both Hindi and Urdu.

In his copiously-researched book Gita Press and the Making of a Hindu India, Akshaya Mukul calls this the ‘The MacDonnell Moment’. He writes: “The decision to allow the use of Devanagri script in the courts along with Persian acted as a gamechanger in the language debate”.

Malviya was pivotal in helping Hindi gain a firm foothold in the regions we know today as Delhi, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar.

Formation of the Muslim League

Disdain and panic – that’s how proponents of Urdu reacted to Sir Mac Donnell’s decision to grant equal status, however symbolic, to both Urdu and Hindi. So when the All India Muslim League was formed to “promote the social, political and cultural aspirations of the Muslims”, its leaders took it upon themselves to promote Urdu in their earliest resolutions.

Hindustani had come to represent the perfect synthesis of several different cultures. But its two components, Hindi and Urdu, were appropriated by religion when the social fabric on which it rested came under threat.

The Partition

The Urdu-speaking Muslim middle class which inhabited the United Provinces (Uttar Pradesh) and Bihar moved to Pakistan in 1947. The muhajirs, as they came to be called, represented a very small minority that exerted considerable political influence in the newly-formed state. The country’s Qaid-e-Azam (Great Leader) Mohammad Ali Jinnah insisted on making Urdu the official language – a decision many historians say fuelled the revolt in predominantly Bengali-speaking East Pakistan.

India on the other hand, took two years after the Partition to pick its official language. In 1950, it replaced Urdu with English, a decision seen to be influenced by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s insistence on cultivating secular credentials. Urdu, however continues to remain one of the twenty officially recognised languages of India.

As recently as September 2015, Pakistan’s Supreme Court ordered the government to replace English with Urdu “because it cannot be understood by the public at large”. Curiously, 48 percent of Pakistan’s 199 million population speak Punjabi. Only 8 percent speak Urdu.

In Indian schools, Urdu was gradually phased out by vernacular languages and more recently by Sanskrit, which as per the 2001 Census was reported as the mother tongue of about 14,000 out of 1.2 billion people.

(Courtesy: The Quint.)