How Ernesto Guevara Became “Che”: The Motorcycle Diaries Revisited

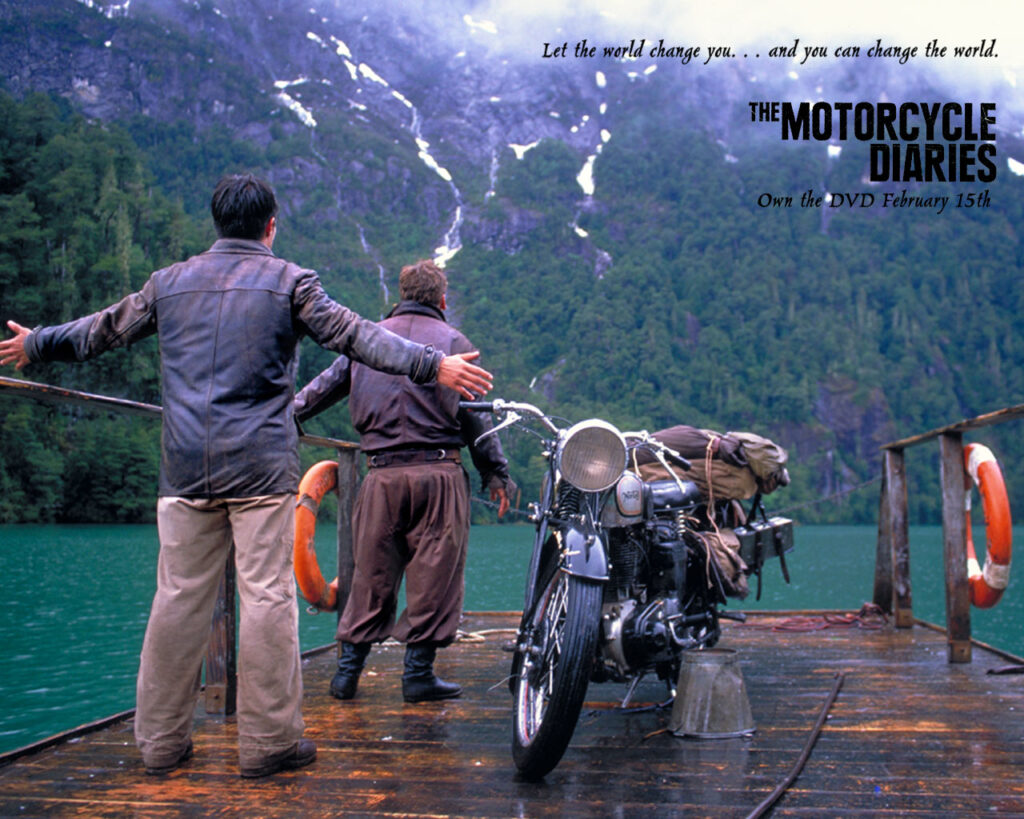

Director Walter Salles 2004 movie, The Motorcycle Diaries—which was inspired by Ernesto (Che) Guevara’a book about his journey from Argentina to Colombia—begins with a quotation from the author himself: “This isn’t a tale of heroic feats.” Sounds good, but that’s not the way that Guevara envisioned his tale when he left his home, his family and his girlfriend, Chichina, as a kind of twentieth century Don Quixote, with a sidekick named Alberto Granado, a biochemist, both of them riding on a Norton 500 they dubbed “La Ponderosa” (“The Mighty One”). Guevara calls himself and Alberto, “Knights of the Road.”

Only with the benefit of hindsight and after seven eventful months on the road that altered his life, did Guevara begin to change his mind about heroism, heroes and heroic feats. At the start of his narrative—that’s based on the journal he kept along the way, and originally titled Notas de Viaje—he wrote of himself and Alberto: “Distant countries, heroic deeds and beautiful women spun around and around in our turbulent imaginations.”

At the age of 23, while still a medical student and not yet a doctor, Ernesto was imbued with many of the ideas and values of the Argentine middle class into which he was born. In 1951 when he and Alberto launched their romantic adventure, Ernesto wanted to be a swashbuckling hero, not a Marxist revolutionary or a guerrilla fighter. On the road, he became another person. He decided that “the poor” were the “unsung heroes” of Latin America.

That was a radical turnaround. “My destiny is to travel,” he wrote on January 31, 1952. Six months later, he exclaimed that “when the great guiding spirit cleaves the world in two antagonistic halves, I knew I would be with the people.

He added, “I see myself immolated in the genuine revolution, the great equalizer of individual will. I steel my body, ready to do battle, and prepare myself to be a sacred space within which the bestial howl of the triumphant proletariat can resound with new energy and new hope.” A poet and a visionary, he was also profoundly spiritual.

Better than Salles’ movie and better than any biography of him, including Jon Lee Anderson’s massive, masterful Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, Che’s Notas de Viaje traces the genesis and the evolution of the vagabond, bohemian and soul mate of Jack Kerouac who joined Fidel Castro in Mexico and in the Sierra Maestra, helped overthrow the Batista dictatorship in Cuba, became a guerrilla in power and aimed to be “The New Man.”

The most recent edition of The Motorcycle Diaries, which was first published in English in 1995 and that was translated from Notas de Viaje, and that first appeared in print in 1993, gives readers the world over the opportunity to watch, kilometer by kilometer, country by country, month by month, the liberation of Ernesto Guevara and the birth of “Che.”

The word has been translated into English as “mate,” “pal,” “man,” “bro,” and “dude.” Take your pick.

Published just now by Seven Stories Press, the new Diary comes with a foreword by Che’s daughter, Aleida Guevara, and another foreword by Che’s Cuban wife, Aleida March, who describes the “travel diaries” as the “adventure of a young man’s journey of discovery.”

Plus there are introductions by billionaire Brazilian filmmaker, and the director of the movie, The Motorcycle Diaries, Walter Salles and by the Cuban writer, Cintio Vitier, best known in the English speaking world for his stunning biography of José Marti.

Over the next eight months, Seven Stories Press will publish nine more books by Guevara, including Latin American Diaries, which is the sequel to The Motorcycle Diaries, Congo Diary from 1965, The Bolivian Diary from 1967, and a volume of his letters. Che fans will see that he fired far more words than bullets and that they hit more targets than they missed.

The Diaries are probably the best place for North American readers to dive into Che’s work which the Times of London described as Das Kapital meets Easy Rider and that The Washington Post described in a patronizing way as “A Latin American James Dean or Jack Kerouac.” In fact, there is no North American Che, no European or Asian Che. There is only one Che.

The main conflict or contradiction in The Motorcycle Diaries is between Che the individualist who wanted to express himself to the fullest and to experience everything that a 20th century human could experience and Che the collectivist who wanted to serve the people and the revolution. Perhaps he never fully resolved the conflict as he saw it, though he tried in Cuba, the Congo, Bolivia and globally on the stage of history.

In The Motorcycle Diaries, he wasn’t yet fully aware of the forces that pulled at him, seemingly in opposite directions at times. He was much more fully aware of those forces in a talk he gave in 1960 to medical students and workers soon after the guerrillas seized power. The talk is included at the end of The Motorcycle Diaries. “The revolution,” Che explained, was “a liberator of human beings’ individual capacity.” It was not “a standardizer of collective will, of collective initiative.”

The Cuban revolution enabled Ernesto to become more Che than he had dreamed possible, though it seems likely that he never fully realized his potential. After all, he was shot and killed at the age of 39 by Bolivian forces acting under orders of the CIA.

Those who have idolized Che—I include myself, along with millions of others—might be disappointed by some of the things that Che does and says in The Diaries. He drinks a great deal and gets drunk. He’s a womanizer who wants to seduce many of the “easy girls” he meets on the road, and, while he empathizes with the poor, the hungry, the homeless and with the lepers at the leper colony that he visits in Peru, he also sometimes looks down at the Indians as dirty, the Blacks as lazy and the leper colony as a “scene from a horror movie.” He’s not yet the New Man he wants to be. He’s on the road.

Salles smoothes over the rough edges in his buddy film that features beautiful landscapes and the endible faces of men, women and children who have toiled close to the earth. Salles also makes Che’s time at the leper colony the crescendo of the film. In the book, the crescendo is Che’s time at Machu Picchu, which he calls “the heart of America,” and where he comes to appreciate the indigenous civilization of the Incas, and where he also despises the inhumanity and brutality of the Spanish conquistadores.

In Machu Picchu, Che thinks about armed resistance to illegitimate authority and authorities. He begins to shed his white identity and imagines himself as “a warrior” who defends “club in hand the freedom of the life of the Inca.”

Always a romantic, he longs for the open road, the quiet of the wilderness and the Amazon jungle. A hobo and a con-artist, too, he and Alberto do what they have to do to survive. While they have an easier time finding food and shelter than the uprooted Indians—the two guys from Argentina often go to the police for help—they come to see, hear and feel the plight of the indigenous people. They also identify as “Pan Americans” who want to unite all the nations of the continent and drive the Yankee imperialists back to where they’ve come from.

A cultural revolutionary, Che wanted to alter “the manner of thinking” that was necessary, he argued, to bring about “external changes, primarily social.” In Hong Kong, Minsk, Bogotá, and wherever citizens go into the streets to demand justice and equality, Ernesto (Che) Guevara lives.

(Jonah Raskin is the author of For The Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman and American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and the Making of the Beat Generation. Courtesy: CounterPunch.)