How many times have we seen it? A hesitant newbie, an invincible opponent, a prestigious title. The odds escalate, self-doubts magnify, doors are shut — till the point when boxing is no longer a sport and the player no longer a person: He’s a symbol, a poster boy of vanishing impossibilities, and the victory a gateway to salvation. You’d think cinema was invented for such a subject, and its echoes have indeed rippled across languages, countries, and generations.

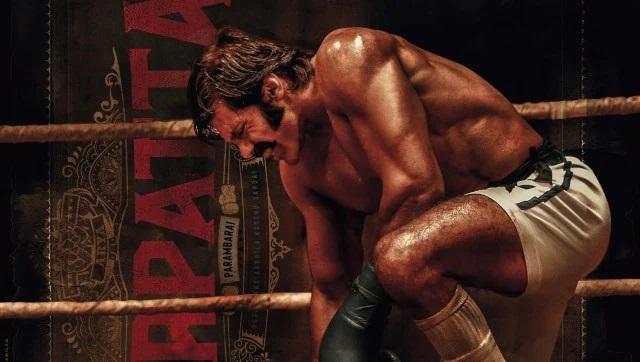

A new Pa. Ranjith drama, Sarpatta Parambarai, streaming on Amazon Prime Video, has all such elements, but two main features distinguish it from its peers: a homegrown visual style – a flourish so decidedly Indian that it is less about seeing and more about being – and a social monstrosity that transcends the distinction between competing parties, for it generates its own resentments and loyalties: the hero, Kabilan (Arya), is a Dalit.

The film opens to an old yet familiar landscape: shipping yards, toiling porters, modest dwellings, dusty gravels, faraway chimneys, industrial fumes. The people, too, seem to belong to a different era: sideburns so sharp and muscular that they deserve their own birth certificates, moustaches so thick that they can qualify for weightlifting championships, and shirts so multi-patterned that they make maximalism quiver. Madras during the period is very well created. The whole thing has a very Deewar feel – a world where the working class could still dare to dream. And sure enough, we soon get the time period: the mid-70s, during the Emergency.

At 173 minutes, Sarpatta Parambarai tells a dense intricate story about two boxing clans: Sarpatta and Idiyappan. Headed by a fierce and idealist coach, Rangan (Pasupathy), who is also a member of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party opposing the Emergency, the Sarpatta clan gets routinely defeated by the Idiyappan boxers. That rivalry has a long history: many years ago, Rangan defeated the now Idiyappan coach, Duraikannu (G.M. Sundar), who quit boxing after that match. Years later, he’s continued to avenge that loss as a coach.

Kabila, (Arya) on the other hand, has grown up admiring Rangan, but his mother (Anupama Kumar) forbids him to fight, because his father Munirathnam, once a fabled boxer, eventually became a henchman and got murdered – a feud also shaped by casteist resentment. So, we get a crucial subversion of the genre: in most boxing films, the main action unfolds inside the ring, but Sarpatta Parambarai depicts a more elemental struggle: Will Kabilan even make it to the ring? That question becomes all the more important because a Sarpatta member had murdered Munirathnam. As if Ranjith seems to be implying, “A rational mind sees allies and foes; a casteist mind sees oppressors and oppressed.”

It’s quite clear, even otherwise, that Ranjith doesn’t want to play by the book. Most sports films, for instance, devote their initial energies to defining and inspiring the underdog. But Kabilan – circling around boxing rings, revering the coach, deflecting other condescending Sarpattas – is not even an underdog: He is a man who was never there, an Eklavya with ten thumbs, ready to do anything for his coach.

So, the initial segment is dominated by the make-up of the local tournament – along with some focus on the key players, the two coaches and Idiyappan’s prime boxer, Vembuli (John Kokken) – which has the flavour of a small-town mela. The spectators crowd the scenes, dousing the characters in a sea of humanity. Sarpatta Parambarai demands a lot from itself – one sequence is often an intersection of several subplots – and, as a result, demands a lot from the audiences. Just its first 25 minutes bombard you with sights and sounds of such high intensity and relentless momentum that you feel like taking a break – and Kabilan hasn’t even entered the ring.

It’s only when Rangan publicly challenges Duraikannu that the film starts to declutter and align. But even then, it takes some time. Rangan promises to bring a new boxer to defeat Vembuli; Duraikannu retorts that if they lose again, the Sarpatta clan will be banned from competing forever. They have two contenders: Rangan’s son, Vetri (Kalaiyarasan), and a boxer from an influential family, Raman (Santhosh Prathap), that once controlled the clan. Rangan chooses Raman, leaving Vetri miffed. But it’s only when Raman disappoints the coach, which involves losing a practice match to Kabilan, our hero enters the picture.

We usually don’t see boxing dramas take so much time before letting their protagonists face the fire. It’s this unpredictable nature of Sarpatta Parambarai’s plot – recognising the winding and contradicting rhythms of life – that lends the film its gritty authenticity. There’s nothing here that just happens; there’s nothing here that is not debated, fought, or sweated over. That’s the real game: the fight outside the ring. At the start, the makers thank Muhammad Ali for his “resilience”– and this film dons that spirit like a badge of honour. Whenever Kabilan’s family tries to better their lot, they’re punished. Punished for who they’re, what they should be.

But Kabilan tries – and tries, and tries some more. Trains under Rangan. Becomes a boxer. Humiliates a fabled Idiyappan member. Almost defeats Vembuli but the match is interrupted by goons who strip him naked in the ring. Gets mired in another violent scuffle and goes to jail. Comes out. Quits boxing. Starts an illicit liquor business. Becomes an alcoholic. Becomes Vetri’s henchman and, in disturbing circularity, starts living his father’s life. Sarpatta Parambarai is multiple films rolled in one, and Kabilan is locked in a sea of boxing rings. Most of his matches have no rewards because you don’t get prizes for reclaiming what was yours: dignity.

So much in this film hides in plain sight – especially because it tackles a ubiquitous evil – that seemingly small scenes gather thundering potency. In most films, for example, a dialogue as simple as “opportunities don’t come our way easily” wouldn’t make you think twice. But here when it’s told to Kabilan, with a photo of B.R. Ambedkar on a street wall in the background, it pops. Or that peach of a line raining goosebumps: “Move with courage, Kabilan. Our time has come.” Or that scene, shortly after Kabilan rides a horse, where Raman’s uncle mocks him. This is a less angry film than Kaala, also by Ranjith, but it doesn’t compromise on vision or courage.

Or take the technical finesse. The sound mixing is precise and sharp, especially as multiple aural sources – charged dialogues, match commentaries, crowd chatter – mark many bouts. The cinematography, often relying on natural light, treats the settings life-like. By eschewing the standard stylisations inherent to Hollywood sports dramas, Sarpatta Parambarai becomes its own film – it becomes our film. The cinematographic smarts (aided by sharp screenwriting) continue to inform and elevate the tense matches, too. The writing underscores the boxers’ strengths and weaknesses, and the camera, giving them literal space, allows us to deduce the duels on our own. Sound design? Raw and visceral. I could feel the punches, the tapping feet, the restless crowd. The editing brings its own ammunition. We often associate it with skillful transitions, but here the technique aspires for something more: impact. Many scenes have excellent synchronicity between the punches and cuts – Selva R.K. cuts when it hurts. The background score, especially in the initial duels, is versatile and terrific: it is catchy, kinetic, and suggestive of something grand, complementing a particularly rooted story.

Such diverse contrasting combinations – uplifting and disturbing, wishful escapism and unflinching realism, entertaining highs and political depths – consistently heighten and sustain tension. But sometimes the two-pronged effort fails. It’s most evident in the subplot centred on Kabilan and his mother. You get the intense import of their conversations, but the overly melodramatic designs – often sounding repetitive and screechy – dull their impact. It’s also the prime reason the film’s most crucial plot turn, sparked by Kabilan’s mother, lacks the requisite fire. Ditto his relationship with his wife (Dushara Vijayan). Even the film’s first song seems planted – as if Ranjith is intent on checking the customary mainstream boxes – which is quickly followed by another song, which doesn’t fit either. But the film’s bigger flaw is prioritising the macro over the micro. It makes sense for a large part, as Sarpatta Parambarai captures the boxing subculture of North Madras with remarkable specificity and, along the way, provides an insightful intersection of sports, culture, and politics. But that focus also deprives the film of the ‘in-between’ moments that usually expand the characters. Making political statements through cinema is of course heartening, but no matter how many lenses you deploy, people are still… people.

A part of Tamil mainstream cinema is clearly having a moment. Over the last few years, it’s produced stunning films of Dalit rebellion: Kaala, Pariyerum Perumal, Asuran, Karnan. They don’t just question the status quo; they tear and chew and spit it out. They depict struggles that deserve the comforting compassion of cinema: of sweat and dissent, soil and tears, honour and iniquity. And, let me be clear, these dramas are good not just because of their ‘message’; they are good on their own, period. Indian mainstream cinema often sides with the bullies, advertising them as ‘heroes’. But the times are changing, and the boxing ring has new players. They’re not just going after the oppressors; their eyes are on the ring itself.

(Courtesy: The Wire.)