Threats Over the External Debt of Developing Countries

[In the first part, we saw that the external indebtedness of developing countries (DC) went through two stages from 2000 to 2018. From 2000 to 2007-2008, the debt stagnated or increased moderately in parallel to negative net transfers. From 2008 to 2018, the opposite happened: debt doubled and net transfers were positive. In this article, we analyse different factors that have a direct influence on the DC’s capacity to carry on making debt repayments.]

Providing that it is legitimate and invested in productive sectors that are essential or useful to the population, debt in itself is not a bad thing. However countries most often fall into the debt trap. When faced with the rising debt of DC, advocates of the dominant economic policy generally claim that the sums borrowed are going to be invested in the economy, generate growth and jobs, improve infrastructure, increase GDP and in fine produce the wealth necessary to repay the debt alongside higher income. The truth is that this interpretation ignores the differential between the amounts borrowed and the amounts actually received after the generous commissions and fees creamed off by the creditors, and also interest rates. It ignores embezzlement of public money, enabled by banking secrecy ensured and defended by big private banks with the support of governments and institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF, the OECD, multilateral regional banks like the Inter-American development banks, the African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the European Investment Bank and so on. It ignores the trade mechanisms and agreements on foreign investment that impoverish States and their populations: free-trade treaties, bilateral treaties on investments, repatriating profits by multinationals, etc. That interpretation also ignores exogenous shocks that severely limit governments’ ability to defend their populations if they are to continue debt repayments: the catastrophic effects of the global environmental crisis, the global health crisis, the global economic crisis. Those who are eager to explain that public indebtedness is a compulsory step for the countries of the South if they want to progress and develop forget to consider the fact that DC are particularly vulnerable to these exogenous factors. No developing country, with the exception of China – which is not really a DC except in the statistics of the World Bank and other international bodies—has the power to make a significant impact on variables like international interest rates, the exchange rate for their national currency against strong currencies, the price of raw materials (or what is known as terms of trade), the great flows of investments, decisions made by multilateral institutions (the IMF, World Bank, WTO etc.). Whenever there is a shock on one or more of these variables, DC can soon find themselves suffocating or at least considerably destabilized.

1. Evolution of the public external debt of DC by type of lender

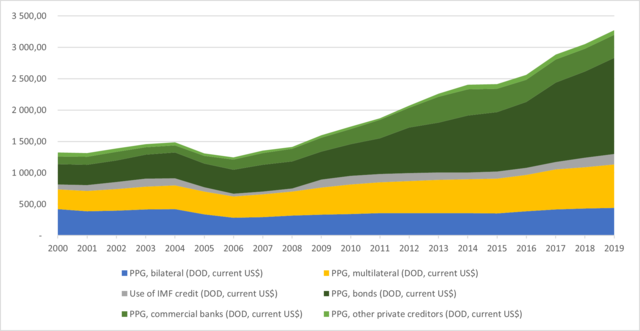

Graph 1: Evolution of the public external debt of DC by type of lender (in billions of $US)

In the graph above, can be seen the two phases described earlier. Furthermore, the lenders can be distinguished, divided into 3 categories:

- In blue: bilateral creditors. These are loans between States.

- In yellow: multilateral creditors. These are loans from the international financial institutions (IMF, World Bank and the development banks).

- In green: private creditors. A distinction is made between: dark green, for credits contracted on the financial markets in the form of sovereign bonds, usually sold on Wall Street; khaki green, for bank loans; and light green for loans from other kinds of private creditor.

While the official bilateral and multilateral creditors hold a roughly stable amount of the DC’s debt in absolute terms, there has been a significant increase of the share held by private creditors, which has climbed from 41 % in 2000 to 62 % in 2018. Although it is true that bank loans have increased, this tendency is mainly due to the weight of bond issues, i.e. sovereign bonds sold by the DC on the financial markets, mainly Wall Street).

Unlike loans from official creditors, private loans have the advantage of not carrying political conditionalities. On the other hand, interest rates are higher and may vary according to the credit rating given by Credit Rating Agencies or the evolution of the benchmark interest rates fixed by central banks.

2. Evolution of interest rates

Graph 2: Evolution of the Prime Rate and the main Central Banks [1] (in %)

In 1979, the FED’s brutal interest rates applied after a unilateral decision by the United States was one of the main factors that triggered the debt crisis in the Third World. Following the subprime crisis in 2007-2008, the Central Banks of Europe and the United States applied a very low interest rate. Without ever really succeeding in improving the economic situation, they have pursued this policy. With the new financial disturbances of Autumn 2019 and the collateral effects of Covid-19, it should be extended, but for how long? If rates were to rise, the cost of debt repayment would increase significantly for the DC. The risk is enhanced by the currency profile of the DC’s debt. 75 % are denominated in US dollars, 9 % in euros, 4.4 % in yen (see graph 3).

Graph 3: Evolution of the composition of the DC’s public external debt by currency (in %) [2]

It is immediately obvious that by far the majority of loans are contracted in US dollars (75 %). Next come, in yellow, loans denominated in euros (9 %) then in red, “all other currencies” (8.4 %). The latter is rising sharply, probably because it rests to a large extent on the yuan, the currency of the State of China, which has become one of the largest lenders to the DC.

Graph 4: Evolution of interest rates on the DC’s loans (in %)

The graph represents the average interest rates paid by the DC. In grey are those owed to private creditors, in orange those owed to official creditors and in blue, the average of both those.

As shown in Part 1, we note a fall in interest rates consecutive to decisions of the Fed and the ECB. Although lower than before, let us consider the level of interest rates. At their lowest between 2013 and 2015, they reached an average of 3%; from 2015 they climbed by an average of 4%. By way of comparison, in 2019-2020 countries like France, Germany, Japan or the United States borrowed at either negative interest rates or at a rate varying between 0 and1%.

An important fact that this graph highlights is a rise in interest rates from 2015. The overall increase in the DC’s debt, their weak credit ratings on the financial markets, in correlation with the end of the super cycle of raw materials and the slowdown in world growth during the trade war between the USA and China, lead creditors to fear a series of defaults on repayments in 2020. Consequently, the lenders “protect” themselves by raising the risk premium that they demand from borrowers from the South. Is a new debt crisis in motion? Is the debt trap closing on the DC? Several factors are developing in that direction; this is what we are about to see.

3. Evolution of exchange rates for DC currencies

To calculate the cost of loans an economy takes out, it is not enough to take into account the interest rates (and risk premiums which make the loans even more expensive); how the value of the debtor country’s currency evolves in relation to the currency in which the loan is denominated also needs to be included. If a country borrows mainly in dollars and its own currency loses, say, 5 % of its value compared to the dollar, the burden of debt repayment will automatically increase. Now most countries of the South have seen their currency depreciate against the dollar during 2020. This is clearly indicated in Table 1.

Table 1: Evolution of exchange rates for 38 DC currencies against the US dollar

between 1 March 2020 and 3 September 2020 [3]

| Currency | Variation (%) | Value on 1 March 2020 | Value on 3 Sept. 2020 |

| MMK Myanmar [Burmese Kyat ] | 6.87 | 1429.64 | 1337.80 |

| CLP Chili [Chilian Peso] | 5.84 | 815.36 | 770.38 |

| PHP Philippines [Philippino Peso] | 5.06 | 51.04 | 48.58 |

| LYD Libya [Libyan Dinar ] | 4.44 | 1.42 | 1.36 |

| TND Tunisia [Tunisian Dinar] | 4.34 | 2.85 | 2.73 |

| MAD Morocco [Moroccan Dirham] | 4.21 | 9.62 | 9.23 |

| CNY China [Chinese Yuan renminbi (RMB)] | 2.10 | 6.98 | 6.84 |

| THB Thailand [ThaiBaht] | 0.35 | 31.55 | 31.44 |

| UGX Uganda [Ugandan Shilling] | 0.22 | 3705.25 | 3697.00 |

| IRR Iran [Iranian Riyal] | 0.17 | 42069.94 | 42000.00 |

| BOB Bolivia [Boliviano] | -0.31 | 6.91 | 6.93 |

| BDT Bangladesh [Taka] | -0.49 | 84.73 | 85.15 |

| IQD Iraq [Iraqi Dinar] | -0.64 | 1190.01 | 1197.66 |

| AFN Afghanistan [New Afghan Afghani (AFN)] | -1.21 | 75.78 | 76.71 |

| EGP Egypt [Egyptian Pound] | -1.54 | 15.62 | 15.86 |

| INR India [Indian Rupee] | -1.77 | 72.23 | 73.53 |

| NGN Nigeria [Nigerian Naira] | -3.45 | 364.00 | 377.00 |

| COP Colombia [Colombian Peso] | -4.00 | 3497.47 | 3643.38 |

| GHS Ghana [Ghanaian Cedi] | -6.64 | 5.35 | 5.73 |

| DZD Algeria [Algerian Dinar] | -6.64 | 120.12 | 128.67 |

| PYG Paraguay [Guarani] | -6.89 | 6517.64 | 6999.71 |

| KES Kenya [Kenyan Shilling] | -6.93 | 101.11 | 108.64 |

| PKR Pakistan [Pakistani Rupee] | -7.06 | 154.04 | 165.74 |

| ZAR South Africa [South African Rand] | -7.11 | 15.57 | 16.77 |

| MZN Mozambique [Metical] | -9.31 | 65.21 | 71.90 |

| MXN Mexico [Mexican Peso] | -9.46 | 19.71 | 21.77 |

| UYU Uruguay [Uruguayan Peso] | -9.58 | 38.57 | 42.65 |

| KZT Kazakhstan [Kazakh Tenge] | -9.66 | 381.52 | 422.31 |

| RUB Russie [Russian Rouble] | -10.98 | 67.06 | 75.33 |

| ETB Ethiopia [Ethiopian Birr] | -12.35 | 32.28 | 36.83 |

| CDF Congo/Kinshasa (DRC) [Congolese Franc] | -13.77 | 1694.59 | 1965.29 |

| TRY Turkey [Turkish Lira] | -16.33 | 6.23 | 7.44 |

| BRL Brazil [Brazilian Real] | -16.46 | 4.49 | 5.37 |

| ARS Argentina [Argentine Peso] | -16.67 | 62.15 | 74.58 |

| AOA Angola [Angolan Kwanza] | -19.47 | 492.22 | 611.20 |

| ZMW Zambia [Zambian Kwacha] | -23.34 | 15.06 | 19.64 |

| VES Venezuela [Venezuelan Bolivar] | -77.97 | 73617.09 | 334183.06 |

| ZWL Zimbabwe [Zimbabwean Dollar] | -78.48 | 17.95 | 83.40 |

Map: Evolution of exchange rates against the US dollar

between 1 March 2020 and 3 September 2020 [4]

Table 1 and the above map present the evolution of the exchange rates for the currencies of 38 DC and the whole world against the US dollar between 1 March 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic became global, and 3 September 2020, when this sub-section was written.

With the exception of the countries of the North, the DC of the Eurozone, the 15 countries of the CFA franc (in West Africa, Central Africa and the Comores), countries whose currencies are indexed on the US dollar (for example, Ecuador) and China, it can be seen that the huge majority of DC currencies depreciated during this period. In fact, this depreciation has been ongoing since 2015. It has been accelerated by the collateral economic consequences of the coronavirus.

Several factors explain these developments.

The ruling classes of the South clearly carry part of the responsibility since they are organizing capital flight. Local ruling classes buy dollars (or any strong currency) to safeguard “their” money in the countries of the North or a tax haven, instead of investing in their own country’s economy. Buying dollars with local currency raises the value of the dollar relative to that currency. This leads the Central Bank of the country concerned to try to limit depreciation of the local currency by buying it back with the dollars it has in its reserves; which in turn results in a fall of the country’s exchange reserves. This is what has been going on in Turkey since 2015. It is also happening on a disastrous scale in Lebanon in 2020. The fall of a Central Bank’s exchange reserves reduces its capacity to make repayments on the sovereign debt in dollars or another strong currency. At a certain point, the country is obliged to declare itself unable to pay, that is, to default wholly or partially on debt repayments. This is what has happened in Argentina and Lebanon in 2020.

Other actors are responsible for the depreciation of local currency: for example big foreign companies that repatriate their profits on a massive scale to their parent company in the North or to foreign investment funds that sell back shares that they previously bought on the relevant country’s stock market. Another factor detrimental to local currencies is the fall in exports and consequent fall in the revenue in dollars that would have accrued from selling export products on the global market.

One more factor explains the depreciation/devaluation of currencies of the South against the dollar: the drastic fall in prices of raw materials starting from 2015 (see Part 3 of this series). Since they are mainly destined for export, a fall in their prices means a proportional fall in State revenue, destabilizing their trade balance (the ratio of imports to exports) to negative. Once that happens, the reserves of foreign currency required for debt payments contract accordingly.

In parallel to this, with depreciation, the amount of local currency needed to be converted into dollars to repay external debt (or internal if the currency is indexed to the dollar, which is quite common) increases greatly, by simple arithmetic. In fact, even if interest rates were to remain historically low (see Part 2) the countries would have to dig ever deeper into their exchange reserves to repay the debt. As export revenues fall as a result of the global economic crisis, brutally and massively aggravated by the effects of Covid-19, the situation is becoming critical for a whole series of DC including so-called emerging countries like South Africa (- 7.11 %), Argentina (- 16.67 %), Brazil (- 16.46 %), India (- 1.77 %) and Mexico (- 9.46 %). Several of those countries are already in a situation of over-indebtedness or suspension of payments.

Footnotes

[1] The Prime rate, here in blue, is the interbanking rate practised by banks for short-term loans they make one another. It is usually 3 points higher than the FED rate. In orange are the interest rates fixed by the US Federal reserve; in grey, those fixed by the European Central Bank; and in yellow, by the Japanese Central Bank. The US dollar, the euro and the yen are the main 3 lending currencies.

[2] This graph shows only the main exchange currencies as indicated by the World Bank. In blue we have the US dollar, in green the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDR – a basket of currencies), in grey the Japanese yen, in yellow the euro and in red “all other currencies”. To make the graph clearer and because their proportion is below 1 %, we have omitted to show the Swiss franc (0.38 %), the British pound sterling (0.27 %) and “miscellaneous currencies” (0.53 %).

[3] Data collected from the website FXTOP. The currency of reference is the US dollar on 3 September 2020. Consulted on 3 September 2020. Accessible at: https://fxtop.com/fr/tendances-forex.php

[4] The more the colour tends towards red and black, the more the national currency has depreciated against the US dollar. The more the colour tends towards dark green, the more the currency has appreciated against the US dollar. Consulted on 3 September 2020. Source : https://fxtop.com/fr/carte-mondiale-taux-change-devises.php

[Eric Toussaint is a historian and political scientist who is the spokesperson of the CADTM International, and sits on the Scientific Council of ATTAC France. Milan Rivié is with the CADTM. Article courtesy: Committee For The Abolition Of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM)]