A hundred and one years ago, as the non-cooperation movement against the colonial British was taking off, a conference with a difference was held at Mangaon, Kolhapur, in western Maharashtra today. It was a conference of the so-called untouchables to foreground their deplorable state in society and join forces for social justice. A young Dr B.R. Ambedkar was invited to chair the event.

“You have found your saviour in Ambedkar…I am confident that he will break your shackles. Not only that, a time will come, so whispers my conscience, that he will shine as a front-rank leader of all-India fame and appeal.” Introducing the chair with these words at the March 1920 conference was the Maharaja of Kolhapur, Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj. The progressive monarch was an unlikely but influential social reformer of late 19th and early 20th century India, a man far ahead of his time.

Born Yashwantrao Ghatge in an aristocratic family, the royal Bhonsale dynasty adopted him. He was taught English, world history and politics. June 26 was his birth anniversary, but, as in other years, it passed without fanfare. A few social and political leaders and the organisations he inspired retraced his formidable legacy, but it was not enough. Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj deserves to be celebrated—not just remembered—and his legacy of reformist work expansively followed across India. He was, after all, the essential link between the path-breaking social reform of Mahatma Jotiba Phule and its anchoring in politics and constitutionalism by Ambedkar.

Phule-Shahu-Ambedkar forms the triumvirate of Maharashtra’s progressive and reformist tradition focussed on backward classes and women. Along with reformists such as Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Mahadev Govind Ranade, they represent the enlightened and liberal path of Maharashtrian, mainly Hindu, society. The binary to this progressive tradition was conservatism and caste-religion supremacy, which found expression through the reactionary Hindutva of VD Savarkar and MS Golwalkar.

Pioneer of Reservation

Shahu Maharaj was barely 20 years old when crowned in 1894. For the next 28 years, till he passed away, he wrote into law and implemented a multitude of reforms for backward classes and women that encompass diverse fields, from education, industry and labour, agriculture, economy and markets, irrigation and dams, among others. It would be difficult and unfair to identify him with any one of them, but if one must, it would have to be as the pioneer of reservations for the weaker sections of society in educational institutions and jobs—a legacy that Ambedkar carried into the Constitution of India nearly five decades later.

Appalled at the Brahmin control over the levers of power in Kolhapur, including in his administration, and agonised by the casteist treatment he faced on one occasion, Shahu Maharaj initiated a far-reaching programme to reserve seats for non-Brahmins in his administrative architecture. It is perhaps the first such reservation, de-Brahminisation of power, in a princely state. The Kolhapur State proclamation issued in 1902 read: “His Highness is pleased to direct that from the date of this order, 50 per cent of the vacancies that may occur, shall be fixed by recruits from among the backward classes.” The term backward classes meant non-Brahmins, especially the so-called untouchables.

Royal religious advisors were typically Brahmin. When they declined to perform religious rites for non-Brahmins citing Vedic restrictions, Shahu Maharaj dared to replace them with a young Maratha scholar and encouraged non-Brahmins to read and recite the Vedas. These steps brought a Brahmin backlash to his doorstep, referred to as the “Vedokta” controversy, but he stayed firm. Shahu Maharaj also abolished hereditary titles and, in 1916, set up the Deccan Rayat Sanstha to secure the political rights of non-Brahmins.

Education as Fulcrum of Reform

From Jotiba and Savitribai Phule’s work, Shahu Maharaj realised the value of liberating education from the clutches of elite castes and making it available to backward classes and women. Transformation of the prevailing exclusive education system lay at the heart of his social reform. He set up a slew of educational institutions from schools to technical colleges and established schools where non-Brahmins could learn Sanskrit and the Vedas. He made primary education universal and free and reserved seats in these institutions so that nobody is denied a chance at education due to birth.

However, it was not easy for the young to study—especially not for women—given the prevalent attitudes or lack of finance. So, scholarships were instituted and hostels opened on a community basis for students. As education opened doors, generations benefited. As they say in Kolhapur, indeed across western Maharashtra, there is not one backward class family whose life is untouched by Shahu Maharaj’s reforms.

To diminish and dismantle the pernicious hold of caste on social life, Shahu Maharaj issued a decree banning caste segregation and untouchability. It was incumbent on all his subjects to treat everyone equally and allow ‘untouchables’ access to public utilities such as village ponds, wells and schools. Ambedkar later expanded this principle of equality in the Constitution. Shahu Maharaj also legalised inter-caste marriages and blessed one such union in the royal household.

When Ambedkar needed funds to start his fortnightly “Mook Nayak” in 1919, Shahu Maharaj donated from his treasury. A year later, when Ambedkar required money to travel to the United Kingdom to study, Shahu Maharaj made good the shortfall and promptly wired him a loan the following year when Ambedkar struggled to pay fees.

Gender Reforms

Inspired by the Phules, Shahu Maharaj expanded on the concept of schools for girls and women and spoke on the need to educate women at every opportunity he got, as his biographers point out. He knew a conservative society needed such conversations and public discourses. Education for women clashed with their marriage because girls were married off at or before puberty. Shahu Maharaj made efforts to stop child marriage through persuasion. When the colonial government moved the Age of Consent Bill, he supported it, though conservatives of the time, such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, staunchly opposed it.

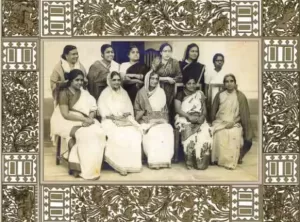

Two other initiatives deserve mention, given the far-reaching effects they had. Shahu Maharaj legalised widow remarriage in 1917, which was greeted with a massive backlash from upper-caste Hindus. Three years later, he introduced a law banning the Devdasi system, widely prevalent in the region, in which young girls were customarily offered to God or temples, leading to their sexual exploitation and mental harassment. The Devdasi system is not yet history, but it is to his credit that he enacted a law against it a century ago.

Other reforms he undertook included establishing agricultural knowledge and training institutes, secular marketplaces where farmers across communities could buy and sell and agricultural exhibitions and fairs. The Chhatrapati Shahu Spinning and Weaving Mill was set up in 1906 to provide industrial employment and encourage ancillary industries in the region. A group of oil-foundry-saw mills were set up in 1912-13 along with cooperative-like credit societies so that the common folk would not be beholden to moneylenders. To make the Kolhapur region self-sufficient and water-fed through the year, Shahu Maharaj also initiated the construction of the Radhanagri dam in 1907, though it completed only decades later.

A keen patron of the arts, Shahu Maharaj set up residencies for writers and researchers in the area and made sure his administration established gymnasiums and wrestling pits to encourage the home-grown sport. Towards the end of his life, he devoted time to Satyashodhak Samaj, the legendary reformist organisation Phule founded.

Relevance today

The stupendous work done by Shahu Maharaj deserves revisiting, especially now, when stories abound of brutal savagery against Dalits and backward classes. Dalits have been assaulted or killed for riding bikes or eating within sight of elite-caste people. Dalit women are raped and tortured regularly. Nine states with a little over half of the SC population registered a staggering 84% of cases of atrocities in 2019, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Even the pandemic did not pause the backlash of upper castes against inter-caste love and Dalit assertion of rights. Studies show that workers who belong to a Scheduled Caste suffer discrimination in both wages and employment rate. A paper co-authored by economist Sukhdeo Thorat showed that SCs form an overwhelming 70.5% of workers in middle and low-level occupations but barely 29% in better quality jobs.

When the Indian Postal Department issued a stamp dedicated to Rajarshi Shahu Maharaj in May 1979, the citation read, “A social revolutionary, a true democrat, a visionary, patron of theatre, music and sports, and the Prince of the Masses.” The reverence that his name evokes in the region, among the legion of followers of the Phule-Shahu-Ambedkar philosophy across Maharashtra, is unparalleled. At a time when caste supremacy and religious intolerance corrode the idea of India, when power is being used to further sectarian interests, his legacy lights the path ahead. It will be a century to his death next May, but the relevance of Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj does not diminish, for social equality is an unfinished project in India.

(The author, a senior Mumbai-based journalist and columnist, writes on politics, cities, media and gender. Courtesy: Newsclick.)