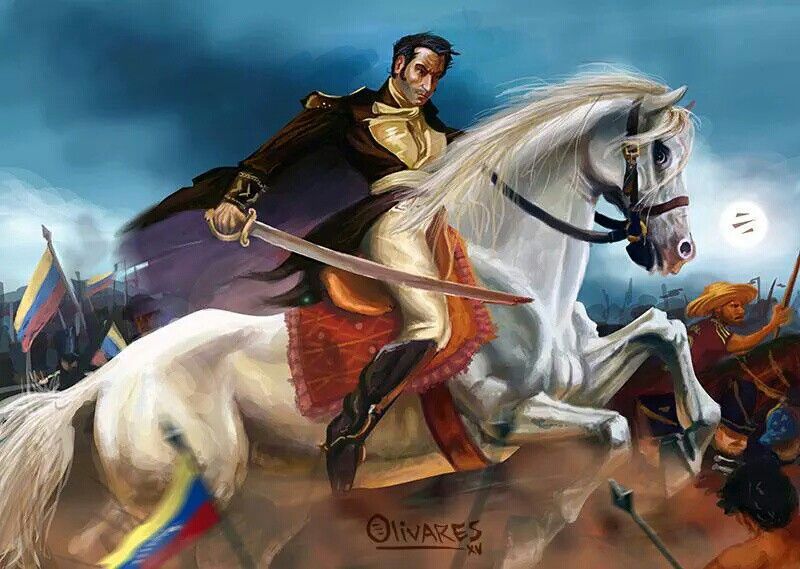

The political and humanist stature of Simón Bolívar, leading figure of the Liberation of Latin America, continues to powerfully inspire the left movements of the continent. Simón Bolívar, a 19th century Venezuelan statesman, embodied the progressive ideals of South American liberation from Spanish colonial power. He advocated the end of the monarchy and insisted on a social revolution based on education to establish full independence. Even today, his universalist thinking continues to inform leftist movements in the continent. Christine Pic-Gillard, author of a new biographical and historical study of the Liberator, goes beyond the myths about Bolívar to examine the reasons why he remains so influential.

Alex Anfruns: You argue that The Liberator Simón Bolívar “did not come out of nowhere”. Who inspired his political action?

Christine Pic-Gillard: Bolívar was, of course, the product of his personal history and the history of his time. His education was marked by the influence of Simón Rodríguez, his school teacher, who transmitted the universalist values of the French Revolution to him. His two stays in Paris allowed him to meet the great figures of the French intelligentsia in the Parisian Salons where liberal ideas circulated. The travel narratives of South America by the naturalists Humboldt and Bonpland, whom he met in Paris, forged his sense of American identity. On the other hand, in his homeland, sporadic acts of rebellion challenged the colonial order; his own father had participated in them.

The atmosphere of the time was, therefore, one of defiance of the established order: revolution in North America, revolution in France, Juntas in Spain, challenges to the role of Spain in South America and particularly in Venezuela. We must not forget the frustrated attempts to liberate Venezuela by Francisco de Miranda, whom Bolívar met in England in 1810 during his first diplomatic mission for the Junta de Caracas. Francisco de Miranda was the first revolutionary figure in the liberation war. Let us also acknowledge José de San Martín, who liberated Argentina before participating with the Bolivarian army in the liberation of Peru.

AA: Simón Bolívar had an unshakable determination and faith in the success of his independence ideals. At what point were the limits of his emancipatory activities revealed?

CP-G: Indeed, Bolívar had an unshakable faith in the success of the liberation war, despite the fact that it had failed at first, due both to the actions of the Spanish army and those of the internal opposition. The first republic failed, and Bolívar had to go into exile. But he mounted an expedition and established a second republic. This then failed and Bolívar had to go into exile again. But he organizes a new expedition and manages to reunite the patriots. His army liberates Venezuela, but the victory will be total only when all the territories are liberated.

He travelled all over South America, from the Caribbean coast to the southern Andes, traversing them in dire conditions, founding republics, writing a constitution, and creating schools. The end of the war of liberation in 1824 and the failure of the Congress of Panama to create a confederation of South American states marked the limit of Bolívar’s emancipatory action. It faced the political ambition of the generals, the surviving colonial social structures, the difficulty of developing a liberal economy, the enormous debt of the new republics, and the appetites of foreign powers, particularly Great Britain and the United States.

AA: In your book, you point out that Bolívar abolished the communal property of indigenous peoples and established private ownership of the land. Historians point to the negative consequences of this measure for the traditional ways of life and organization of the indigenous population.

CP-G: The Spanish colonization had preserved some pre-Columbian structures, such as communal property and the exploitation of the lands of indigenous communities. The suppression of these communities in 1824, to create a class of small proprietors, was an economic and social failure. The lands were bought by the aristocrats to form estates in which the indigenous people work under a contract that keeps them in bondage through debt. The indigenous people are under the control of a foreman who has orders to prevent any escape. When the property inheritance changes hands, the indigenous people are part of the sale. The hacienda is a bad economic model: it consumes half of what it produces. In fact, the agricultural worker is obliged to buy on the farm what he needs: tools, clothes, food. To get rich, the landlord has to expand his patrimony. It cannot be said that the expropriation has totally destroyed the traditional organization of indigenous populations. It favoured cultural syncretism and undoubtedly accelerated the acculturation already well established since the conquest.

AA: One of Bolívar’s emblematic projects was a confederation that would bring together Latin American countries, the only way to free itself in the long term from the control of foreign powers. How do you explain its failure?

CP-G: The idea of a confederation is the basis of Bolívar’s political project. He saw the different Hispanic American territories as a cultural whole, and he knew that only the union of the new republics would allow them to resist foreign pressure and develop economically and socially, in peace, thanks to a large market with common interests. The independentistas do not share this political project, firstly because they do not have a long-term vision of the future of the new republics, and secondly because they think in terms of personal ambition. Military leaders want to establish their political power over sovereign territory, without having to share it with a central government. So they dragged their feet.

That project also worried the United States and Great Britain for political and economic reasons. The congress of Panama that the Confederation was to make a reality was emptied of its orientation even before it was held, by the negotiations of the United States with the South American leaders. So much so that Bolívar himself withdrew from attending. The door was then open to internal wars and foreign control.

AA: The most common explanation for the shortcomings of Latin American politics is the tendency of its leaders to “caudillismo”, that personal and authoritarian form of government. Do you think this concept is useful to understand Bolívar’s emancipatory action?

CP-G: Bolívar faced caudillismo from the beginning of his liberating and emancipating action. His thinking was extremely progressive in the sense that he defended universalist values. His project was not only to free the South American territories from the clutches of Spain. It was a political revolution: rejecting the monarchy to build republics that would be grouped into a confederation of South American states. It was also a social revolution: through education, creating a middle class capable of developing countries through science and technology. This political vision was not understood by the independentistas who distrusted Bolívar, like Miranda, or betrayed him, like Manuel Piar and later Santander. Bolívar himself never succumbed to caudillismo. Every time he was elected head of a country, he handed over his power to the authorities, who often did not accept it!

AA: The textbooks of Spanish-American civilization limit themselves to presenting Bolívar as if he were an imported marketing product from the 19th century. What do you think of the Latin American governments and political movements that anchor their identity in Bolivarian thought?

CP-G: Bolivarian thought is complex and its references are not always understood by those who take it as a model. Bolívar drew on ancient references: Greek and Roman history provided him with models. For example, when he became a “dictator” it was with the attributes of the Roman dictator, whose political life was short: he was called to exercise his authority in a moment of crisis and then surrendered his power. On the basis of a wrong interpretation, Bolívar has been vindicated by the authoritarian right in Europe.

Latin American political movements have better understood Bolivarian thought, especially its universalist thought based on the need for human progress in general, regardless of individual interests. Starting from the local to reach the universal, taking power to put it in the hands of the people. On the other hand, Bolívar was the creator of the awareness of the specificity of the South American identity, made up of all the cultural and ethnic contributions, closely linked to the phenomenal nature of this land. It is in this sense that it was and continues to be a model for national revolutions, both in Cuba and in Venezuela.

(Alex Anfruns is a journalist, translator and political scientist. Courtesy: l’Humanité Dimanche.)